NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Phenobarbital is a barbiturate that is widely used as a sedative and an antiseizure medication. Phenobarbital has been linked to rare instances of idiosyncratic liver injury that can be severe and even fatal.

Background

Phenobarbital (fee" noe bar' bi tal) is a barbiturate and is believed to act as a nonselective depressant. Phenobarbital also has anticonvulsant activity and is thought to act by suppressing spread of seizure activity by enhancing the effect of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), raising the seizure threshold. Phenobarbital was introduced into clinical medicine in 1911 but was never subjected to critical controlled studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy. For these reasons, phenobarbital is now considered of unproven benefit in controlling seizures. Nevertheless, it is commonly used for prevention and management of partial and generalized seizures, usually as an adjunctive agent in combination with other anticonvulsants. Phenobarbital is also used for sedation and insomnia although its use for these conditions is now uncommon. Phenobarbital is also used in fixed combinations with other antispasmodics or anticholinergic agents and used for gastrointestinal complaints, including irritable bowel syndrome. The typical starting dose in treating seizures in adults is 60 to 100 mg in three divided doses daily. Oral formulations of tablets or capsules of 15, 16, 30, 60, 90 and 100 mg are available in multiple generic forms. Parenteral formations and oral elixirs for pediatric use are also available. Phenobarbital has declined in general use in recent years with availability of more efficacious and better tolerated agents. Its major advantage is low cost, but it is more sedating than other anticonvulsants. Frequent side effects include drowsiness, sedation, hypotension, and skin rash. Uncommon but potentially severe adverse events included severe sedation, dependence, hypersensitivity reactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Hepatotoxicity

Prospective studies suggest that less than 1% of subjects develop elevations in serum aminotransferase levels during long term phenobarbital therapy. Clinically apparent hepatotoxicity from phenobarbital is rare but can be abrupt in onset, severe and even fatal. Phenobarbital hepatotoxicity typically occurs in the setting of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome with onset of fever, rash, facial edema, lymphadenopathy, elevations in white count and eosinophilia occurring 1 week to several months after starting therapy. Liver involvement is common, but is usually mild and anicteric and overshadowed by other features of hypersensitivity (rash, fever). In some cases, hepatic involvement is more prominent with marked elevations in serum enzyme levels, jaundice and even signs of hepatic failure. The typical pattern of serum enzyme elevations is mixed, but can be hepatocellular or cholestatic. Liver biopsy shows mixed hepatitis-cholestatic injury with prominence of eosinophils and occasionally granulomata. Re-exposure usually results in recurrence and should be avoided.

Likelihood score: B (likely rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

The mechanism of phenobarbital hepatotoxicity is thought to be hypersensitivity or an immunological response to a metabolically generated drug-protein complex.

Outcome and Management

Phenobarbital hepatotoxicity is usually rapidly reversible with improvements beginning within 5 to 7 days of stopping the drug and being complete within 1 to 2 months. In cases of severe injury, progression to acute liver failure and death can occur. Corticosteroids have been used but with uncertain effectiveness. Prolonged cholestasis can occur, but chronic injury and vanishing bile duct syndrome have not been reported from phenobarbital therapy. Cross reactivity with other aromatic anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, and lamotrigine) is common but not invariable. Patients with hypersensitivity to phenobarbital should be monitored carefully if they are to start other aromatic anticonvulsants.

Drug Class: Anticonvulsants, Sedatives and Hypnotics

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Phenobarbital – Generic, Luminal® Sodium

DRUG CLASS

Anticonvulsants

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

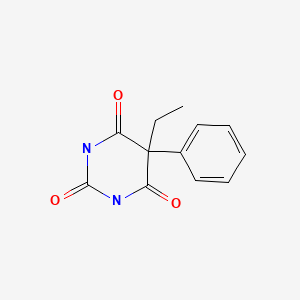

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenobarbital | 50-06-6 | C12-H12-N2-O3 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 30 July 2020

Abbreviations used: DRESS, drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SJS/TEN, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Zimmerman HJ. Anticonvulsants. In, Zimmerman, HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999: pp. 498-516.(Expert review of anticonvulsants and liver injury published in 1999; mentions that liver injury from phenobarbital is rare, but it has been implicated in at least 15 cases of clinically apparent injury, both hepatocellular and cholestatic).

- Pirmohamed M, Leeder SJ. Anticonvulsant agents. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013: pp 423-41.(Review of anticonvulsant induced liver injury mentions that clinically apparent hepatotoxicity from phenobarbital is rare and that cross sensitivity to hepatic injury from other aromatic anticonvulsants occurs, but is not invariable).

- Smith MD, Metcalf CS, Wilcox KS. Pharmacology of the epilepsies. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 303-26.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Birch CA. Jaundice due to phenobarbital. Lancet. 1936;i:478–9.

- Welton DG. Exfoliative dermatitis and hepatitis due to phenobarbital. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143:232–4. [PubMed: 15415251](25 year old pregnant woman developed rash, followed by facial and peripheral edema, itching, erythema, desquamation, and high fever 6 weeks after starting phenobarbital [white blood count 73,000, 32% eosinophils] and was jaundiced for a few weeks but ultimately recovered).

- McGeachy TE, Bloomer WE. The phenobarbital sensitivity syndrome. Am J Med. 1953;14:600–4. [PubMed: 13040367](3 cases of severe phenobarbital reactions seen between 1933 and 1947; two men and one woman, ages 27 to 41 years, developing rash, desquamation, fever, delirium and jaundice within 1-2 weeks of starting drug; one instance was fatal).

- Pagliaro L, Campesi G, Aguglia F. Barbiturate jaundice. Report of a case due to a barbital-containing drug, with positive rechallenge to phenobarbital. Gastroenterology. 1969;56:938–43. [PubMed: 4238546](31 year old woman developed rash, fever and facial edema after 2 doses of "barbital" and by 7 days developed jaundice [bilirubin 24.1 mg/dL, ALT 200 U/L, Alk P 15 BU] which was prolonged; rechallenge with phenobarbital caused recurrence of fever, rash and jaundice [19 mg/dL]; three biopsies were done, but vanishing bile duct syndrome was evidently not present).

- Weisburst M, Self T, Peace R, Cooper J. Jaundice and rash associated with the use of phenobarbital and hydrochlorothiazide. South Med J. 1976;69:126–7. [PubMed: 128822](18 year old woman developed rash followed by fever, anorexia, lymphadenopathy and jaundice [bilirubin 7.2 mg/dL, AST 250 U/L, Alk P 350 U/L], with rapid resolution although no mention of drug being stopped).

- Evans WE, Self TH, Weisburst MR. Phenobarbital-induced hepatic dysfunction. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1976;10:439–43.

- Shapiro PA, Antonioli DA, Peppercorn MA. Barbiturate-induced submassive hepatic necrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74:270–3. [PubMed: 7468565](71 year old woman developed rash on phenytoin and was switched to mephobarbital and 3 months later developed anorexia and fatigue followed by jaundice 6 weeks later [bilirubin 5.3 mg/dL, ALT 837 U/L, Alk P 320 U/L], improved slowly but relapsed with restarting phenobarbital; biopsy showed submassive necrosis, ultimately recovering completely; no features of hypersensitivity).

- Jacobi G, Thorbeck R, Ritz A, Janssen W, Schmidts HL. Fatal hepatotoxicity in child on phenobarbitone and sodium valproate. Lancet. 1980;1:712–3. [PubMed: 6103126](Child given valproate [36 mg/kg] and phenobarbital for 3 months developed confusion and coma [bilirubin 9.7 mg/dL, ALT 60 U/L, high ammonia and protime], ultimately dying; more likely due to valproate than phenobarbital hepatotoxicity).

- Spielberg SP, Gordeon GB, Blake DA, Goldstein DA, Herlong HF. Predisposition to phenytoin hepatotoxicity assessed in vitro. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:722–7. [PubMed: 6790991](3 patients with phenytoin hepatotoxicity had dose dependent cytotoxicity of lymphocytes exposed to microsomal metabolized drug [arene oxides]; clinical onset arose 4, 4 and 1 week after starting phenytoin, with rash, fever and jaundice; [bilirubin 7.8, 11.5 and 0.5 g/dL, AST 790, 2340 and 62 U/L, eosinophils 9%, 10% and 10%], all 3 recovered).

- Lane T, Peterson EA. Hepatitis as a manifestation of phenobarbital hypersensitivity. South Med J. 1984;77:94. [PubMed: 6695234](4 year old boy developed fever and rash about 1 week after starting phenobarbital and 1 week later was found to have ALT 273 U/L [no bilirubin reported], rapidly improving with stopping).

- Knutsen AP, Anderson J, Satayaviboon S, Slavin RG. Immunologic aspects of phenobarbital hypersensitivity. J Pediatr. 1984;105:558–63. [PubMed: 6332892](Seven patients with hypersensitivity reactions arising 2-23 days after starting phenobarbital with fever and a pruritic rash which was confluent and desquamating; 2 patients had abnormal liver tests, but without jaundice; 3 had eosinophilia, 3 IgE elevations; 2 decreased C4 levels; several had positive lymphocyte stimulation tests to phenytoin or phenobarbital).

- Fonseca JC, Azulay DR, Rozembau I, Azulay RD. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:187–92. [Hypersensitivity syndrome caused by phenytoins and phenobarbital] Portuguese. [PubMed: 6237236]

- Kahn HD, Faguet GB, Agee JF, Middleton HM. Drug-induced liver injury. In vitro demonstration of hypersensitivity to both phenytoin and phenobarbital. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1677–9. [PubMed: 6466024](16 year old girl developed fever, facial edema, lymphadenopathy and rash 3 weeks after starting phenobarbital and phenytoin; stopping phenytoin had no effect, but she improved with stopping phenobarbital and had positive lymphocyte stimulation tests to both).

- Palomeque A, Doménech P, Martínez-Gutiérrez A, Lequerica P. An Esp Pediatr. 1986;24:328–30. [Severe hypersensitivity to phenobarbital with erythema multiforme, cholestatic hepatitis and aplastic anemia] Spanish. [PubMed: 3740671](11 year old girl developed rash, fever, adenopathy, somnolence and facial edema 4 weeks after starting phenobarbital [bilirubin 6.7 to 42.8 mg/dL, ALK 1380 to 2980 U/L, Alk P 855 to 3146 U/L], with confluent necrosis and central collapse on liver biopsy, transient episode of aplastic anemia during recovery).

- Shear NH, Spielberg SP. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: in vitro assessment of risk. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1826–32. [PMC free article: PMC442760] [PubMed: 3198757](Lymphocyte cytotoxicity found in response to drug metabolites from 53 patients with hypersensitivity to anticonvulsants, including 35/36 to phenytoin, 22/27 to phenobarbital and 25/27 to carbamazepine; 51% had hepatitis).

- Roberts EA, Spielberg SP, Goldbach M, Phillips MJ. Phenobarbital hepatotoxicity in an 8-month-old infant. J Hepatol. 1990;10:235–9. [PubMed: 2332596](8 month old boy with seizures given phenobarbital for 2 weeks developed rash followed by fever with eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis and jaundice [bilirubin 2.9 mg/dL, ALT 430 U/L, Alk P 135 U/L], slow recovery, positive lymphocyte cytotoxicity test).

- Horsmans Y, Larrey D, Pessayre D, Rueff B, Degott C, Benhamou JP. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1991;15:648–52. [Atrium-related hepatitis. Report of four cases] [PubMed: 1684328](Atrium, a fixed combination of phenobarbital and two carbamates, was implicated in 4 cases of hepatotoxicity arising 1-4 months after starting [normal bilirubin, ALT 1.5-21 fold elevated] with mild symptoms of asthenia, but no fever or rash and resolving within 1-3 months of stopping).

- Pariente EA, Mineur D. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16:485–6. [Atrium-induced hepatitis with autoimmune pattern] [PubMed: 1526409](Patient developed fatigue one month after starting Atrium and clomethacine [bilirubin normal, ALT 16.5 times ULN, GGT 10 times ULN, ANA 1:160], resolved with stopping but recurrence of fatigue, ALT elevation and ANA/SMA positivity with two rechallenges: HLA A1, A9, B8, B27).

- Handfield-Jones SE, Jenkins RE, Whittaker SJ, Besse CP, McGibbon DH. The anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:175–7. [PubMed: 7654579](3 cases of fever and rash arising 3, 4 and 10 weeks after starting phenytoin or carbamazepine; two required steroids; only 1 had hepatitis; one died of multiorgan failure, others switched to valproate or clobazam without recurrence).

- Brocheriou I, Zafrani ES, Mavier P. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17:305–6. [Severe acute hepatitis caused by Atrium] [PubMed: 8339895](29 year old man developed jaundice after 7 months of Atrium therapy [also on valproate and phenobarbital] with abdominal pain and jaundice [bilirubin 10 mg/dL, ALT 200-4056 U/L, ANA 1:200], biopsy showed no fat, recurrence with rechallenge of Atrium, but not valproate).

- Horsmans Y, Lannes D, Pessayre D, Larrey D. Possible association between poor metabolism of mephenytoin and hepatotoxicity caused by Atrium, a fixed combination preparation containing phenobarbital, febarbamate and difebarbamate. J Hepatol. 1994;21:1075–9. [PubMed: 7699230](Hydroxylation index of mephenytoin [CYP 2C] was assessed in 24 patients with drug induced hepatitis, found index higher [12.4] in 3 patients with Atrium hepatitis than in controls [1.8] and other patients [2.5], attributed abnormality to a defect in mephenytoin oxidation).

- Di Martino V, Mallat A, Duvoux C, Zafrani ES, Dhumeaux D. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18:904–5. [Severe hepatitis caused by phenobarbital] [PubMed: 7875406](Patient on phenobarbital for 1 month developed fever and rash followed by adenopathy and jaundice [bilirubin 8.7 mg/dL, ALT 22 times ULN, elevated protime], treated with prednisone and recovered within 1 month).

- Schneider S, Charles F, Chichmanian RM, Montoya ML, Rampal P. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1995;19:1064–5. [Acute hepatitis associated with microvesicular steatosis induced by Atrium] [PubMed: 8729422](37 year woman developed abdominal pain 6 months after starting Atrium [bilirubin 2.0 mg/dL, ALT 9 times ULN, Alk P 0.8 times ULN, ANA 1:1000], biopsy showed microvesicular fat; also taking carbimazole and phenytoin).

- Cayla JM, Fandi L, Arnould P, Degott C, Gouffier E. Presse Med. 1995;24:1665. [Atrium 300 hepatitis. A new case] [PubMed: 8545391](65 year old woman was found to have ALT elevations [5 times ULN] 3 months after starting Atrium, with rapid resolution on stopping and recurrence with rechallenge; no jaundice but some fatigue).

- Wallace SJ. A comparative review of the adverse effects of anticonvulsants in children with epilepsy. Drug Saf. 1996;15:378–93. [PubMed: 8968693](Systematic review; ALT elevations occur in 4% of children on phenytoin, 6% on valproate, 1% on carbamazepine but not with phenobarbital; mentions that severe skin reactions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been linked to phenobarbital use).

- Schlienger RG, Shear NH. Antiepileptic drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Epilepsia. 1998;39 Suppl 7:S3–7. [PubMed: 9798755](Review of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome; onset 2-8 weeks after starting therapy with aromatic anticonvulsants presenting with high fever, rash, adenopathy and pharyngitis followed by organ involvement, most commonly the liver [~50%], but also hematologic, renal or pulmonary; eosinophilia, blood dyscrasias, nephritis; sometimes facial edema, oral ulcers, hepatosplenomegaly, myopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, atypical lymphocytosis; rash usually exanthema with pruritus, occasional follicular pustules or exfoliative dermatitis and erythroderma, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).

- Knowles SR, Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1999;21:489–501. [PubMed: 10612272](Review of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: triad of fever, rash and internal organ injury occurring 1-8 weeks after exposure to anticonvulsant; liver being most common internal organ involved. Occurs in 1:1000-1:10,000 initial exposures to phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital or lamotrigine, unrelated to dose, perhaps predisposed by valproate; liver injury arises 1-4 weeks after onset of rash and ranges in severity from asymptomatic ALT elevations to icteric hepatitis to acute liver failure. High mortality rate with jaundice; other organs include muscle, kidney, brain, heart and lung. Pseudolymphoma syndrome and serum sickness-like syndrome are separate complications of anticonvulsants. Role of corticosteroids uncertain; cross reactivity among the agents should be assumed).

- Lachgar T, Touil Y. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 2001;33:173–5. [The drug hypersensitivity syndrome or DRESS syndrome to phenobarbital] [PubMed: 11434197](78 year old woman developed rash and fever 3 weeks after starting phenobarbital [ALT 3 times ULN, eosinophilia], resolving within a month of stopping).

- Turner RB, Kim CC, Streams BN, Culpepper K, Haynes HA. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome associated with Bellamine S, a therapy for menopausal symptoms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5) Suppl:S86–9. [PubMed: 15097937](Patient developed fever, rash and facial edema followed by jaundice 2 months after starting Bellamine S which contains phenobarbital, belladonna and ergotamine [bilirubin 2.4 mg/dL, ALT 97 U/L, Alk P 160 U/L, 14% eosinophils], and then developed complications of herpes zoster and meningitis during prednisone therapy for the hypersensitivity, and later had recurrence during carbamazepine therapy for neuralgia).

- Autret-Leca E, Norbert K, Bensouda-Grimaldi L, Jonville-Béra AP, Saliba E, Bentata J, Barthez-Carpentier MA. Arch Pediatr. 2007;14:1439–41. [DRESS syndrome, a drug reaction which remains bad known from paediatricians] [PubMed: 17997290](6 year old girl with epilepsy developed rash, fever and eosinophilia 3 weeks after starting phenobarbital [ALT 5 times ULN, Alk P 1.5 times ULN], improving clinically with corticosteroid therapy; switched to topiramate and valproate without recurrence).

- Tohyama M, Hashimoto K, Yasukawa M, et al. Association of human herpes virus 6 reactivation with the flaring and severity of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:934–40. [PubMed: 17854362](Anti-HHV-6 testing of 100 patients with drug induced hypersensitivity syndrome [34% with hepatitis] found rise in IgG levels in 62 patients, largely in more severe cases; HHV-6 DNA detected in 18; drugs included carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, allopurinol, sulfasalazine and mexiletine).

- Di Mizio G, Gambardella A, Labate A, Perna A, Ricci P, Quattrone A. Hepatonecrosis and cholangitis related to long-term phenobarbital therapy: an autopsy report of two patients. Seizure. 2007;16:653–6. [PubMed: 17574447](Two men, ages 44 and 40 years, on long term phenobarbital had sudden death and were found to have granulomas and portal inflammation on autopsy).

- Björnsson E. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiepileptic drugs. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:281–90. [PubMed: 18341684](Review of anticonvulsant hepatotoxicity, mentions that phenytoin associated liver injury usually occurs as a part of a hypersensitivity syndrome, in 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 persons, 100 published cases, mean onset at 4 weeks, 13% mortality; in contrast, phenobarbital has only rarely been reported to cause liver injury).

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J., Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected between 2004 and 2008, 18 cases were attributed to anticonvulsants, no case was attributed to phenobarbital).

- Ferrajolo C, Capuano A, Verhamme KM, Schuemie M, Rossi F, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC. Drug-induced hepatic injury in children: a case/non-case study of suspected adverse drug reactions in VigiBase. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:721–8. [PMC free article: PMC2997312] [PubMed: 21039766](Worldwide pharmacovigilance database contained 9036 hepatic adverse drug reactions in children, phenobarbital accounting for 41 cases [0.4%] for an adjusted odds ratio of 6.6).

- Molleston JP, Fontana RJ, Lopez MJ, Kleiner DE, Gu J, Chalasani N., Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Characteristics of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury in children: results from the DILIN Prospective Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:182–9. [PMC free article: PMC3634369] [PubMed: 21788760](Among 30 children with drug induced liver injury enrolled in a prospective US database between 2004 and 2008, 8 were due to anticonvulsants [lamotrigine in 3, valproate in 3, phenytoin in 1 and carbamazepine in 1], none were attributed to phenobarbital).

- Zhang LL, Zeng LN, Li YP. Side effects of phenobarbital in epilepsy: a systematic review. Epileptic Disord. 2011;13:349–65. [PubMed: 21926048](Review of the side effects of phenobarbital focusing upon cognitive adverse effects).

- Drugs for epilepsy. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2013;11:9–18. Erratum in Treat Guidel Med Lett 2013; 11: 112. [PubMed: 23348233](Concise review and guidelines to use of anticonvulsants; phenobarbital is listed under "other drugs" and said to be effective for partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures; no mention of hepatotoxicity).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, including 1 attributed to phenytoin among only 410 persons receiving the drug in Iceland; none were attributed to phenobarbital).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A, Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America. An analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:231–9. [PubMed: 24552865](Systematic review of literature of drug induced liver injury in Latin American countries published from 1996 to 2012 identified 176 cases, 7 [4%] of which were attributed to anticonvulsants including 3 to phenytoin, 3 to valproate and 1 to carbamazepine, but none were attributed to phenobarbital).

- Devarbhavi H, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced liver injury due to antimicrobials, central nervous system agents, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:145–61. [PubMed: 24879980](Review of drug induced liver injury caused by several drug classes including antiepileptics, which account for 2-11% of all cases in various registries; a common presentation is with DRESS, particularly with the older agents such as carbamazepine, phenytoin and phenobarbital and often associated with reactivation of human herpes virus 6 or 7).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al. United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, 40 [4.5%] were due to anticonvulsants including 12 due to phenytoin, 9 lamotrigine, 7 valproate, 4 carbamazepine, 3 gabapentin, 2 topiramate and 1 each for ethosuximide, fosphenytoin, and pregabalin; but none were attributed to phenobarbital).

- Chalasani N, Reddy KRK, Fontana RJ, Barnhart H, Gu J, Hayashi PH, Ahmad J, Stolz A, Navarro V, Hoofnagle JH. Idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in African-Americans is associated with greater morbidity and mortality compared to Caucasians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1382–8. [PMC free article: PMC5667647] [PubMed: 28762375](Among subjects enrolled in a US prospective database of drug induced liver injury, causes more frequent in African Americans than Caucasian were trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, methyldopa, phenytoin and allopurinol, and African Americans were more likely to have severe skin adverse events [2.1% vs 0.4%], fatal or transplantation outcomes [10% vs 6%] as well as chronic injury [24% vs 16%]).

- Vidaurre J, Gedela S, Yarosz S. Antiepileptic drugs and liver disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;77:23–36. [PubMed: 29097018](Review of the use of anticonvulsants in patients with liver disease recommends use of agents that have little hepatic metabolism such as levetiracetam, lacosamide, topiramate, gabapentin and pregabalin, levetiracetam being an "ideal" first line therapy for patients with liver disease because of its safety and lack of pharmacokinetic interactions).

- Drugs for epilepsy. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59(1526):121–30. [PubMed: 28746301](Concise review of the drugs available for therapy of epilepsy mentions that phenobarbital and primidone are effects for therapy of partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures, but have a higher incidence of sedation that other drugs).

- Borrelli EP, Lee EY, Descoteaux AM, Kogut SJ, Caffrey AR. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis with antiepileptic drugs: An analysis of the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2318–24. [PMC free article: PMC6420776] [PubMed: 30395352](Review of adverse event reports to the FDA between 2014 and 2018 identified ~2.9 million reports, 1034 for SJS/TEN, the most common class of drugs being anticonvulsants with 17 of 34 having at least one report, those most frequently linked being lamotrigine [n=106], carbamazepine [22], levetiracetam [14], phenytoin [14], valproate [9], clonazepam [8] and zonisamide [7], whereas phenobarbital is not listed; no mention of accompanying liver injury).

- Han XD, Koh MJ, Wong SMY. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in a cohort of Asian children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:324–9. [PubMed: 30920020](Among 10 children with DRESS syndrome seen at a single, Singapore referral center between 2006 and 2016, 3 cases were attributed to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, 2 to carbamazepine, 1 sulfasalazine, 2 phenobarbital and 1 to levetiracetam [latency 28 days]; all had ALT elevations [88 to 1172 U/L], bilirubin was elevated in 7, but none had acute liver failure and none were fatal).

- Cano-Paniagua A, Amariles P, Angulo N, Restrepo-Garay M. Epidemiology of drug-induced liver injury in a University Hospital from Colombia: Updated RUCAM being used for prospective causality assessment. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:501–7. [PubMed: 31053545](Among 286 patients with liver test abnormalities seen in a single hospital in Colombia over a 1 year period, 17 were diagnosed with drug induced liver injury, the most common cause being antituberculosis therapy [n=6] followed by anticonvulsants [n=3, 1 each due to phenytoin, gabapentin and valproate]).

- Sridharan K, Daylami AA, Ajjawi R, Ajooz HAMA. Drug-induced liver injury in critically ill children taking antiepileptic drugs: a retrospective study. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2020;92:100580. [PMC free article: PMC7138958] [PubMed: 32280391](Among 41 children admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit who received anticonvulsants for seizure control, 5 of 9 receiving phenobarbital alone, 9 of 12 receiving phenytoin alone but none of six receiving valproate developed liver test abnormalities [all hepatocellular], the timing, height and outcome of which were not given).

- Sharpe C, Reiner GE, Davis SL, Nespeca M, Gold JJ, Rasmussen M, Kuperman R, et al. NEOLEV2 INVESTIGATORS. Levetiracetam versus phenobarbital for neonatal seizures: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20193182. [PMC free article: PMC7263056] [PubMed: 32385134](Among 83 newborns with seizures of any caused treated with intravenous phenobarbital or levetiracetam for 5 days, seizure-free status at 24 hours was achieved more frequently with phenobarbital [80% vs 38%] which also had more frequent side effects; monitoring of laboratory data demonstrated “no significant treatment-emergent trends”).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Combination of antiseizure medications phenobarbital, ketamine, and midazolam reduces soman-induced epileptogenesis and brain pathology in rats.[Epilepsia Open. 2021]Combination of antiseizure medications phenobarbital, ketamine, and midazolam reduces soman-induced epileptogenesis and brain pathology in rats.Lumley LA, Marrero-Rosado B, Rossetti F, Schultz CR, Stone MF, Niquet J, Wasterlain CG. Epilepsia Open. 2021 Dec; 6(4):757-769. Epub 2021 Oct 23.

- Efficacy of Fosphenytoin as First-Line Antiseizure Medication for Neonatal Seizures Compared to Phenobarbital.[J Child Neurol. 2021]Efficacy of Fosphenytoin as First-Line Antiseizure Medication for Neonatal Seizures Compared to Phenobarbital.Alix V, James M, Jackson AH, Visintainer PF, Singh R. J Child Neurol. 2021 Jan; 36(1):30-37. Epub 2020 Aug 19.

- Review Barbiturates.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Barbiturates.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Mild hypothermia fails to protect infant macaques from brain injury caused by prolonged exposure to Antiseizure drugs.[Neurobiol Dis. 2022]Mild hypothermia fails to protect infant macaques from brain injury caused by prolonged exposure to Antiseizure drugs.Ikonomidou C, Wang SH, Fuhler NA, Larson S, Capuano S 3rd, Brunner KR, Crosno K, Simmons HA, Mejia AF, Noguchi KK. Neurobiol Dis. 2022 Sep; 171:105814. Epub 2022 Jul 8.

- Review Lamotrigine.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Lamotrigine.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Phenobarbital - LiverToxPhenobarbital - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...