Clinical Description

Childhood ataxia with central nervous system hypomyelination / vanishing white matter (CACH/VWM) phenotypes range from a congenital or early-infantile form (onset age <1 year) to an early childhood-onset form (onset age 1 to <4 years), a late-childhood/juvenile-onset form (onset age 4 to <18 years), and an adult-onset form (onset ≥18 years [Hamilton et al 2018]. Both the childhood and juvenile forms have been observed in sibs; the infantile and juvenile/adult forms have never been observed within the same family [Hamilton et al 2018].

Neurology. The neurologic signs depend on the age of onset [Hamilton et al 2018]. In the congenital and early-infantile forms, the encephalopathy is severe, seizures are often a predominant clinical feature, and decline is rapid and followed quickly by death. In early and late childhood-onset forms, motor decline predominates with ataxia and spasticity. Cognitive decline is relatively mild. Adult-onset forms usually present with cognitive decline and mood and personality changes; motor decline comes later in the disease course. Optic atrophy is variable and rather late in all forms.

The rate of disease progression depends on the age of onset. For individuals with disease onset before age four years, the decline is in general more rapid and more severe the earlier the onset. For onset after age four years, the disease course is generally slower and milder and life span is longer. For this later-onset group, however, variation in severity is wide and does not correlate with specific age at onset [Hamilton et al 2018]. Chronic progressive decline can be exacerbated by rapid deterioration during febrile illness or following minor head trauma or fright; such exacerbations are more common in early-onset than in later-onset forms of the disease [Hamilton et al 2018]. Rarely, a child or an adult with normal neurologic examination and biallelic pathogenic variants in one of the genes listed in Table 1 is identified by brain MRI that is performed because of headache or dizziness [Fontenelle et al 2008]. Follow up of such individuals for more than ten years may show no neurologic deterioration [Hamilton et al 2018; R Schiffmann, unpublished data].

Ovarian failure. While the juvenile and adult forms are often associated with primary or secondary ovarian failure – a syndrome referred to as "ovarioleukodystrophy" [Schiffmann et al 1997, Fogli et al 2003], ovarian failure may occur in any of the forms regardless of age of onset; it has been found at autopsy in infantile and childhood cases [van der Knaap et al 2003]. Because the affected individuals were prepubertal, the ovarian dysgenesis was not clinically manifest.

Antenatal form. The antenatal-onset form presents in the third trimester of pregnancy with oligohydramnios and decreased fetal movement [van der Knaap et al 2003, Hamilton et al 2018]. Clinical features that may be noted soon after birth include feeding difficulties, vomiting, hypotonia, mild contractures, cataract (sometimes oil droplet cataract), and microcephaly. Apathy, intractable seizures, and finally apneic spells and coma follow. Other organ involvement can include hepatosplenomegaly, renal hypoplasia, pancreatitis, and ovarian dysgenesis.

The clinical course is rapidly and relentlessly downhill; the adverse effect of stress factors is less clear. So far, all infants with neonatal presentation have died within the first year of life [Hamilton et al 2018].

Infantile form. A rapidly fatal severe form of CACH/VWM is characterized by onset in the first year of life and death a few months later [Fogli et al 2002, Hamilton et al 2018]. Affected infants develop irritability, stupor, and rapid loss of motor abilities, with or without a preceding intercurrent infection.

A specific infantile-onset phenotype was described as "Cree leukoencephalopathy" because of its occurrence in the native North American Cree and Chippewayan indigenous population [Fogli et al 2002]. Infants typically have hypotonia followed by sudden onset of seizures (age 3-6 months), spasticity, vomiting (often with fever), developmental regression, blindness, lethargy, and cessation of head growth, with death by age two years.

Early childhood-onset form. Initially most children develop normally; some have mild motor or speech delay. New-onset ataxia is the most common initial symptom between ages one and four years. Some children develop dysmetric tremor or become comatose spontaneously or acutely following mild head trauma or febrile illness [Hamilton et al 2018].

Subsequently, generally progressive deterioration results in increasing difficulty in walking, tremor, spasticity with hyperreflexia, dysarthria, and seizures. Once a child becomes nonambulatory, the clinical course may remain stable for several years. Swallowing difficulties and optic atrophy develop late in the disease.

Head circumference is usually normal; however, severe progressive macrocephaly occurring after age two years has been reported [Hamilton et al 2018]; microcephaly has also been observed. The peripheral nervous system is usually normal, although predominantly sensory nerve involvement has been reported [Federico et al 2006, Huntsman et al 2007]. Intellectual abilities are relatively preserved.

The time course of disease progression varies among individuals even within the same family, ranging from rapid progression with death occurring one to five years after onset to very slow progression with death occurring decades after onset.

Late childhood/juvenile-onset form. Children develop symptoms between ages four and 18 years. They often have a slowly progressive spastic diplegia, relative sparing of cognitive ability, and likely long-term survival with long periods of stability and even temporary improvement of motor function [Hamilton et al 2018]. However, the disease course is highly variable and rapid progression and death after a few months have also been described [Hamilton et al 2018].

Adult-onset form. Behavioral problems associated with cognitive decline are frequently reported before neurologic symptoms appear [Labauge et al 2009, Hamilton et al 2018]. Acute, transient neurologic symptoms (optic neuritis, hemiparesis) or severe headache – as well as primary or secondary amenorrhea in females – can be the presenting symptoms.

Asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic adults with two pathogenic variants in one of the genes and a typically affected sib have also been described [Leegwater et al 2001, Hamilton et al 2018].

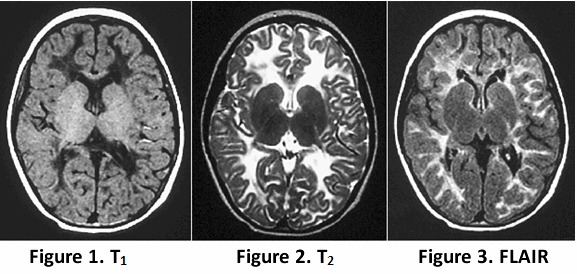

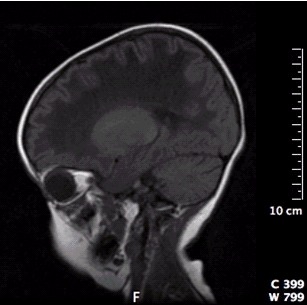

Neuropathologic findings in general are a cavitating orthochromatic leukodystrophy with rarity of myelin breakdown and relative sparing of axons [Bugiani et al 2010]. Vacuolization and cavitation of the white matter are diffuse, giving a spongiform appearance. Cerebral and cerebellar myelin is markedly diminished. The spinal cord is also affected [Leferink et al 2018]. Oligodendrocytes are increased in number, whereas astrogliosis is feeble [Bugiani et al 2011]. The hallmark is the presence of oligodendrocytes with "foamy" cytoplasm and markedly abnormal astrocytes with few stunted processes [Wong et al 2000, Bugiani et al 2011]. The white matter astrocytes and oligodendrocytes are immature and are, in fact, astrocyte and oligodendrocyte precursor cells, explaining the lack of myelin production and scarce gliosis [Bugiani et al 2011, Bugiani et al 2013].