TRIO-NDD due to Gain-of-Function Variants

Developmental delay. The majority of individuals with TRIO gain-of-function variants are reported to have moderate-to-severe developmental delay affecting motor, speech, and cognition.

Among all individuals for whom information on independent sitting was available, approximately one third (6/17) achieved sitting by age 14 months. Seventy-five percent (13/17) achieved sitting by 36 months. For one affected individual, independent sitting occurred after age six years [Kloth et al 2021]. Two individuals, age 24 months and age three years one month, respectively, were not yet able to sit independently [Barbosa et al 2020, Kloth et al 2021]. Upon last assessment, walking was attained for seven individuals, with onset of walking ranging from 20 months to seven years [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Of those who walked independently, 70% did so by age three years and 80% by age five years. Among the ten individuals who were nonambulatory at last assessment, the oldest were age six to ten years [Barbosa et al 2020; Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Information on use of first words was available for 16 individuals, seven of whom were verbal. Earliest use of first words was at age 12 to 15 months [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data], and oldest age at first words was 5.5 years [Barbosa et al 2020]. Individuals who were nonverbal were ages 24 months to ten years two months [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Intellectual disability is likely present in all individuals. However, no formal IQ assessments have been reported in individuals with TRIO gain-of-function variants.

Neurobehavioral manifestations. Among individuals with a TRIO gain-of-function variant, autism spectrum disorder or autistic findings were reported in 27% (4/15 individuals), including three individuals who had a formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Poor attention was reported in 56% (9/16), stereotypies in 47% (8/17), and obsessive-compulsive behavior in 47% (7/15). Aggressive behavior was a feature in 29% (5/17), with one of these individuals described as having temper tantrums. Disrupted sleep has been described in a few individuals in the literature although it is likely underreported [Varvagiannis, personal communication].

Seizures occurred in 37% of individuals (7/19) for whom information was available. Variable types of seizures have been reported, including nocturnal seizures in two individuals, absence seizures, and myoclonic movements of the extremities and eyelids [Barbosa et al 2020; Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. One of these individuals developed seizures at age 30 years [Barbosa et al 2020]. Two further individuals had abnormal EEGs or suspected drop seizures not captured on EEG recordings [Barbosa et al 2020]; thus, seizures may be present in up to 47% (9/17 individuals).

Macrocephaly.

TRIO gain-of-function variants are often associated with absolute macrocephaly (61% of individuals) [Barbosa et al 2020; Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Occipital frontal circumference (OFC) three or more standard deviations (SD) above the mean has been reported in four individuals. One of these individuals had an OFC of 4.7 SD above the mean [Barbosa et al 2020]. An additional two individuals were reported to have relative macrocephaly [Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Additional neurologic manifestations included tremor in two individuals, dystonia in two individuals, and ataxia and/or wide-based ataxic gait in two individuals [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. One individual had an EMG suggestive of very mild demyelinating peripheral neuropathy [Barbosa et al 2020].

Brain MRI abnormalities. Although the total number of individuals who have had a brain MRI is not known, abnormal brain imaging was reported in five individuals. Four individuals had dilated ventricles [Barbosa et al 2020; Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Two were described as having enlarged inner and outer cerebrospinal fluid spaces, and two were diagnosed with hydrocephalus (one of these individuals had a history of intraventricular hemorrhage in the neonatal period) [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Abnormal corpus callosum was a feature in three individuals, in two of whom the corpus callosum was thin [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data], and in one there was hypoplasia/agenesis of the corpus callosum [Kloth et al 2021]. Delayed myelin maturation, Arnold-Chiari malformation, loss of white matter volume, and dysgenesis of anterior commissure with colpocephaly were among variable findings within these five individuals.

Feeding difficulties. Neonatal and infantile feeding difficulties including poor suck, impaired bottle feeding, swallowing difficulties, and frequent vomiting or regurgitation are common, resulting in poor weight gain. Silent aspiration was reported in one individual. Gastrointestinal reflux appears to contribute to these difficulties in some individuals. Feeding difficulties required nutritional support in approximately 30% of individuals, routinely by tube feeding (gastrostomy or less frequently nasogastric). Poor weight gain and early growth deficiency was reported in 80% of infants for whom this information was available.

Growth. The majority of older individuals continued to have poor weight gain; in 67% of individuals (12/18) weight on last examination was reported to be two or more SD below the mean; no individuals with gain-of-function variants were reported to have weight two or more SD above the mean. Short stature (height ≥2 SD below the mean) was reported in 31% of individuals (5/16).

Gastrointestinal manifestations. Gastroesophageal reflux may contribute to feeding difficulties, although the exact frequency is not known. Episodic vomiting has been reported in a few individuals [Barbosa et al 2020]. Constipation appears to be frequent, occurring in 38% of reported individuals. Rare findings reported in single individuals include intestinal malrotation requiring surgery as well as eosinophilic esophagitis [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Musculoskeletal features. Scoliosis was reported in 44% of individuals [Barbosa et al 2020; Kloth et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. In two individuals, abnormal spine curvature occurred early and/or necessitated surgery [Barbosa et al 2020, Kloth et al 2021]. Kyphosis was described in two individuals. Short and/or tapering fingers were described in 35% of individuals.

Dysmorphic facial features.

Barbosa et al [2020] analyzed facial photos of affected individuals using quantitative facial phenotyping. Comparisons of facial features were performed between all individuals with TRIO-NDD and controls and between those with TRIO gain-of-function or loss-of-function variants and controls. Significant clustering was only observed between persons with a TRIO gain-of-function variant compared to matched controls, leading to the suggestion of a distinctive facial gestalt.

Presence of a tall forehead and prominent ears appear to be common [Gazdagh, personal communication]. In the cohort of 20 individuals, the following features were described in more than one individual:

Prominent or tall forehead in six individuals, with frontal bossing in six additional individuals

Highly arched eyebrows reported in three individuals. with synophrys reported in two

Hypertelorism in two individuals, and downslanted palpebral fissures in two individuals

Low-set ears in three individuals, and large ear lobes in two individuals

Wide mouth, everted vermilion of the upper lip, and high palate in two individuals each

Micro-/retrognathia in two individuals

Dental abnormalities. Among the 15 individuals evaluated for dental anomalies, five had relevant findings. These included advanced eruption in one individual [Barbosa et al 2020] and delayed eruption in one individual [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. One additional individual had absence of the second molars at age 37 months [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Dental crowding was present in three individuals [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Cardiac anomalies were present in 11% of individuals. These included one individual with bicuspid aortic valve, aortic regurgitation, and prominent aortic root [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data], and a second individual with atrioventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and type A interrupted aortic arch type.

Genitourinary anomalies include three individuals with neurogenic bladder [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data] and two individuals with enuresis, one of whom had recurrent urinary tract infections.

Other

TRIO-NDD due to Loss-of-Function Variants

Developmental delay. Delayed attainment of milestones is reported in all individuals. Mild-to-moderate developmental delay is typically observed. Severe delay appears to be very rare.

Independent sitting was achieved in 19 individuals, in 80% of these by the age of 14 months. Two individuals were not sitting independently at their last assessment (ages 21 months and 16 years, respectively) [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. The majority of individuals were also ambulatory (20/24). The range for onset of walking was age 12 to 36 months [Barbosa et al 2020], with 80% of individuals ambulatory by age 22 months. Four individuals were nonambulatory at last assessment (ages 20 months, 21 months, 3.5 years, and 16 years, respectively) [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

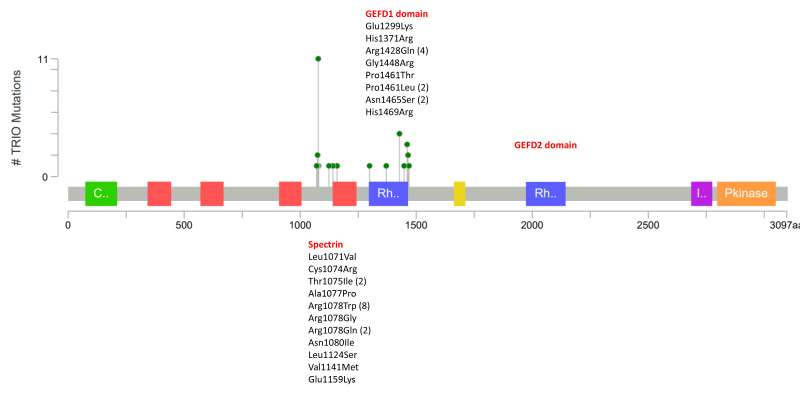

First words occurred by the age of 48 months in 80% of the 20 individuals who were verbal. Four individuals were nonverbal at last assessment (ages 21 months, 3.5 years, 14 years, and 16 years, respectively) [Barbosa et al 2020; Kolbjer et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. The individual who was nonverbal at age 16 years had an intragenic in-frame multiexon TRIO deletion spanning the GEFD1 domain [Kolbjer et al 2021; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Intellectual disability. Most individuals have intellectual disability. Formal IQ assessment has been reported in only four individuals. Two individuals had borderline intellectual functioning (IQ scores of 81 and 78, respectively); two individuals had mild intellectual disability (IQ scores of 62 and 68, respectively) [Ba et al 2016].

Behavioral phenotype. Behavioral findings have been reported in 94% of individuals. Poor attention was reported in 79% (22/28); at least three individuals were diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Obsessive-compulsive findings were reported in 45% of individuals (8/23). Aggressive behavior was reported in 44% (12/27); in two of these individuals, self-mutilating behaviors were reported [Ba et al 2016; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Autism spectrum disorder or autistic findings were described in 40% (10/27); four of these individuals received a formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. Approximately 25% (6/26) presented with stereotypies. In one individual this manifested as echolalia and "balancing" (no additional description of "balancing" was included in the report) [Barbosa et al 2020]. Hand flapping was a feature in an additional individual [Schultz-Rogers et al 2020]. Disrupted sleep has been described in a few individuals in the literature, although it is likely underreported [Varvagiannis, personal communication].

Seizures were reported in 24% of individuals with a TRIO loss-of-function variant. Seizures were more common in individuals with a truncating variant (30%-35%). Only one in ten individuals with a TRIO missense variant in the GEFD1 domain (see Molecular Genetics) had seizures. Reported seizure types included febrile seizures during early childhood, myoclonic seizures, and absence seizures with eyelid and forehead myoclonus refractory to treatment [Schultz-Rogers et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. One individual had various types of seizures at age four years [Barbosa et al 2020]. An adolescent with a TRIO intragenic deletion had severe developmental delay and a history of refractory seizures.

Microcephaly. Approximately 70% of individuals (25/35) had microcephaly [Ba et al 2016, Pengelly et al 2016, Barbosa et al 2020, Schultz-Rogers et al 2020]. Severe microcephaly (>3 SD below the mean) was reported in at least 15 individuals, including three individuals with an OFC average of 6 SD below the mean [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Note: Macrocephaly was reported in two individuals with a TRIO loss-of function variant [Schultz-Rogers et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Brain MRI abnormalities. Although the total number of individuals who have had a brain MRI is not known, six individuals had abnormal brain imaging. In three individuals there was partial agenesis or hypoplasia of the corpus callosum [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Ventricular anomalies were found in two individuals, including abnormal aspect of the lateral ventricle and ventriculomegaly [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Other anomalies observed in single individuals included progressive leukoencephalopathy, lissencephaly, and interhemispheric cyst [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Feeding difficulties. Neonatal and infantile feeding difficulties including poor suck, impaired bottle feeding, and swallowing difficulties are common and result in poor weight gain. Gastrointestinal reflux appears to contribute to these difficulties in some individuals. Feeding difficulties required nutritional support (e.g., tube feeding) in 22% of individuals. Poor weight gain and early growth deficiency was reported in 72% of infants for whom this information was available.

Growth. Some individuals had persistent poor weight gain; in 30% of individuals (8/27), weight on last examination was reported to be two or more SD below the mean. However, 11% individuals (3/27) with loss-of-function variants were reported to have weight two or more SD above the mean. Short stature (height ≥2 SD below the mean) was reported in 14% of individuals (4/29).

Gastrointestinal manifestations. Gastroesophageal reflux may contribute to feeding difficulties, although the exact frequency is not known. Episodic vomiting has been reported in a few individuals [Barbosa et al 2020]. Constipation may be more frequent in individuals with a TRIO loss-of-function missense variant (7/11; 63%) compared to those with a truncating variant (5/14; 36%). One individual with a TRIO intragenic deletion had an anal fistula [Ba et al 2016].

Toe syndactyly. Five individuals were reported to have 2-3 toe syndactyly [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Short and/or tapering fingers are described in 45% of individuals (14/31).

Additional digit anomalies. Less common digit anomalies reported in individuals with TRIO loss-of-function variants included swelling (or broad) proximal interphalangeal joints (five individuals), fifth finger clinodactyly (five individuals), and proximally placed thumb (one individual).

Other musculoskeletal features. Scoliosis was less frequent in individuals with loss-of-function variants and was observed in 15% (4/27). Kyphosis was described in two individuals. Pectus excavatum was reported in two individuals [Ba et al 2016; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Dysmorphic facial features.

Barbosa et al [2020] analyzed facial photos of affected individuals using quantitative facial phenotyping. Comparisons of facial features were performed between all individuals with TRIO-NDD and controls and between individuals with TRIO gain-of-function or loss-of-function variants and controls. Significant clustering was not identified in persons with loss-of-function variants.

Upslanted palpebral fissures, tubular nose, and bulbous nose appear to be common in individuals with a TRIO loss-of-function variant [Gazdagh, personal communication]. Among the 36 individuals reported, the following dysmorphic features were described: facial asymmetry (five individuals), tall forehead (three individuals), broad forehead (one individual), synophrys (four individuals), highly-arched eyebrows (one individual), thick or thick and straight eyebrows (two individuals), upslanted palpebral fissures (three individuals), hypertelorism (two individuals), large and/or protruding ears (seven individuals), abnormal ear helices (two individuals), abnormal nasal configuration (most individuals), thin vermilion of the upper lip (four individuals), thick vermilion of upper and lower lips (three individuals), high palate (five individuals), and micro-/retrognathia (at least eight individuals).

Dental anomalies. Approximately 60% of individuals had dental anomalies, including delayed eruption in 30% (7/24) and advanced eruption in one of 24 individuals. Dental crowding was present in 30% (8/27). Hypodontia/oligodontia was reported in two sibs. One additional individual had hypodontia, although this was also present in an unaffected sib [Barbosa et al 2020]. Other findings included abnormality of the enamel/caries (three individuals), macrodontia of incisors (two individuals), and microdontia (one individual).

Cardiovascular abnormalities. Structural defects were reported in 12% of affected individuals (3/26). These included two individuals with an atrial septal defect [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data] and tetralogy of Fallot in one individual [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]. Arrhythmia has been reported in two individuals with TRIO truncating variants. While in one individual presence of the conduction defect was suspected [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]; the second individual had an additional KCNJ2 pathogenic variant that could be the cause of the arrhythmia [Pengelly et al 2016].

Ophthalmologic manifestations were reported in four individuals. Each of the following were reported in one individual each: visual problems suggestive of bilateral macular pathway dysfunction with pale optic discs, total optic atrophy and poor vision, strabismus, and nasolacrimal duct obstruction [Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data].

Other

Urinary incontinence (two individuals), although one had syringomyelia [

Barbosa et al 2020; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]

Brisk reflexes (two individuals) [

Ba et al 2016; Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]

Bilateral accessory nipples (one individual) [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]

Unilateral cleft lip (one individual) [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]

Profound neonatal anemia (one individual) [Gazdagh et al, unpublished data]