Context and Policy Issues

Group A Streptococcus (GA Strep) also referred to as Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, or Streptococcus pyogenes is a gram positive bacteria which causes a variety of disease conditions and complications.1–4 These include conditions such as pharyngitis (throat infection), skin infections, and more serious conditions such as glomerulonephritis, sepsis, rheumatic heart disease, toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis.5–7 Pharyngitis is one of the common conditions that present at the primary health care facilities or emergency departments.1 Pharyngitis arises commonly from viral infection and less commonly from bacterial infection.4 It is estimated that GA Strep accounts for 20% to 40% of cases of pharyngitis in children and 5% to 15% in adults.4,8 It is associated with considerable cost to society; in the US the estimated annual cost incurred from GA Strep pharyngitis in children is between $224 and $539 million.1

Accurate and rapid diagnosis of GA Strep is important as if left untreated, there is a possibility that throat and skin infections could lead to severe life-threatening invasive conditions as well as post infection immune mediated complications.5 Diagnosis of GA strep is challenging, which makes it difficult to decide on the appropriate care pathway. It is difficult to distinguish between GA strep infection and viral infection.1 Antibiotics are useful to treat pharyngitis from bacterial infection but not viral infection. A 2015 publication, reported that in America, 60% to 70% of primary care physician visits by children with suspected pharyngitis result in antibiotics being prescribed.9 Information regarding antibiotic prescribing for suspected pharyngitis, specifically for Canada was not identified. Considering the issue of antimicrobial resistance which is on the rise, unnecessary use of antibiotics could be detrimental, hence accurate diagnosis is important.

Diagnostic tests based on throat culture are generally considered as the gold standard for diagnosing GA Strep.1,3,10 However, these culture based tests are associated with a time lag between sample collection and obtaining test results, and may take up to 48 hours.1 It may not always be feasible for the patient to return to the clinic and get appropriate treatment based on test results or while waiting for test results, there is a possibility that the patient’s symptoms may worsen. Several non-culture-based, rapid tests for diagnosing GA Strep are available. However, there is considerable variability in sensitivities of these tests, ranging from 55% to 100%11 and these tests may have cost implications. Several clinical decision rules (also referred to as clinical prediction rules) based on clinical characteristics are available to assist in the diagnosis of GA strep infection. These include scoring tools such as Centor, modified Centor (McIsaac), Breese, Wald, Attia, FeverPAIN, and Joachim.9,12,13 These tools are particularly useful in low-resourced settings where laboratory testing facilities may not be available.14 However, the clinical decision tools have been reported to have low positive predictive value, ranging between 35% to 50% for correctly predicting GA strep pharyngitis.15

The purpose of this report is to review the clinical utility of clinical decision rules for the initial screening of patients with suspected Group A Streptococcal (GA Strep) infection. Additionally, this report aims to review the evidence-based guidelines regarding the diagnosis of suspected GA strep infection.

Research Question

What is the clinical utility of clinical decision rules for the initial screening of patients with suspected group A strep infection?

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the diagnosis of suspected group A strep infection?

Key Findings

Limited evidence of variable quality, suggests that the use of a clinical decision rule tool, for initial identification of patients with GA strep infection, may reduce unnecessary testing and inappropriate antibiotic use; however the findings were not always statistically significant.

Three guidelines, which did not mention any specific clinical decision rule tool, recommend that if signs and symptoms are suggestive of bacterial infection then further testing should be undertaken. One guideline recommends the use of McIsaac tool to identify patients who warrant further testing. One guideline recommends the use FeverPAIN or Centor to identify patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic treatment. Findings need to be interpreted in the light of limitations.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline and Embase via Ovid, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. To address question one, no filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. To address research question two, methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and guidelines. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2013 and April 17, 2018.

Rapid Response reports are organized so that the evidence for each research question is presented separately.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2013. Studies which did not actually report on clinical utility outcomes but made predictions based on diagnostic accuracy parameters were excluded. Guidelines which did not mention a systematic literature search were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included randomized controlled trials and observational studies were critically appraised using the Downs and Black checklist,16 and guidelines were assessed with the AGREE II instrument.17 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were narratively described.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

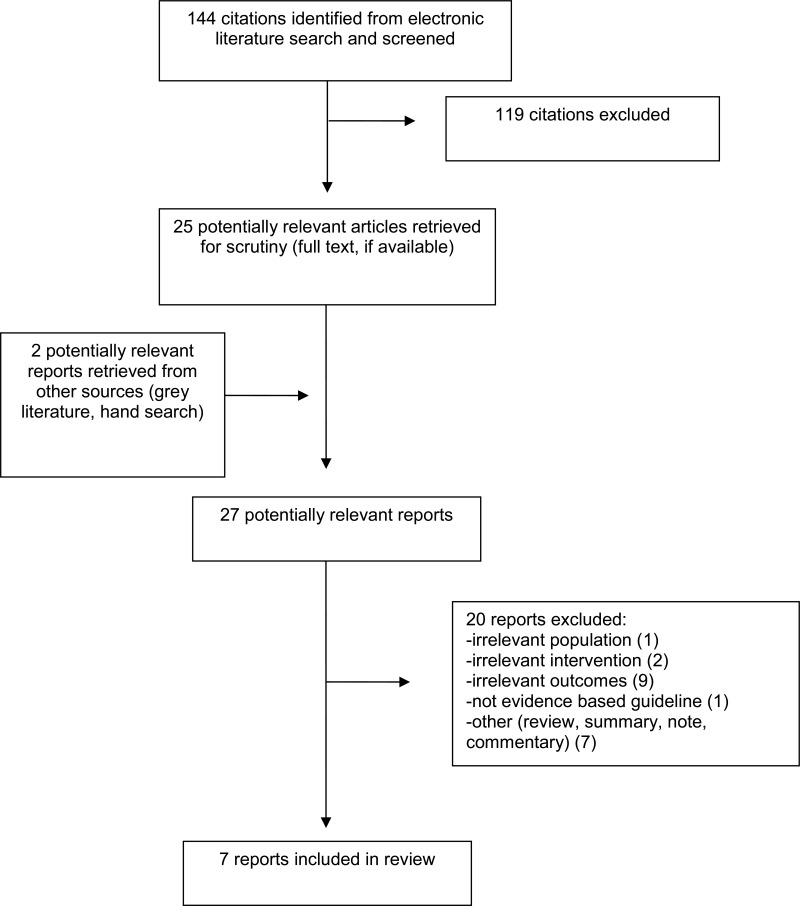

A total of 144 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 119 citations were excluded and 25 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Two potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 20 publications were excluded for various reasons, while seven publications.12,13,15,18–21 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprise one RCT,19 one observational study,12 and five guidelines.13,15,18,20,21

Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are summarized below and details are available in Appendix 2, to .

Study Design

One RCT,19 one retrospective observational study12 and five evidence-based guidelines.13,15,18,20,21 were identified. The RCT19 was conducted at two primary care practices at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. The observational study12 was a before and after study at a hospital. Four guidelines15,18,20,21 mentioned a systematic literature search and the fifth guideline13 did not explicitly mention it in the guideline document but the associated guidelines manual indicates requirement for a systematic literature search. The guideline development group for four guidelines15,18,20,21 included health care professionals in relevant areas and one guideline18 in addition included consumers. The fifth guideline13 did not explicitly mention the guideline development group but the associated guidelines manual indicates that the group comprises experts in relevant areas as well as lay persons. One guideline21 graded the recommendations and the other four guidelines13,15,18,20 did not present grading for the recommendations.

Country of Origin

The RCT19 was published in 2013 and was conducted in the USA. The observational study was published in 2016 and was conducted in Malaysia. One guideline was published in 2018 by the National Institute for Healthcare Excellence (NICE) in the UK;13 two guidelines were published in 2016, one each from Germany18 and one by the High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA;20 one guideline was published in 2015 by the Working Group on the Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Hong Kong College of Paediatricians in Hong Kong;15 and one guideline was published in 2013 in the USA.18

Patient Population

The RCT19 included two groups of patients with suspected pharyngitis and each patient group was assigned to a particular provider group working in an electronic health records environment. The total number of providers was 168 and the total number of patient visits to the provider was 984. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the two provider groups. The median age of the patients was 46 years and the proportion of female participants was 23.4%. There was a statistically significant difference in median age between the two patient groups but no statistically significant difference with respect to other demographics.

The observational study12 included pediatric patients with sore throat in a hospital setting. The mean age was 3.8 years, and the proportion of female participants was 48%. There was a statistically significant difference in mean age between the two patient groups (Groups A & B, i.e. before and after the enforcement of a clinical decision rule) but no statistically significant difference with respect to other demographics. The mean age was 4.1 years for the 60 patients in Group A, and 3.4 years for the 56 patients in Group B; P = 0.04.

For the guidelines, the intended users were pediatricians and primary care physicians;15 clinicians involved in the care of adults with upper respiratory tract infections;20 health professionals, and patients, and their families;13 clinicians in any setting;18 and appeared to be clinicians but was not explicitly mentioned.21 The target patient populations were children with acute pharyngitis;15 adults with acute respiratory tract infections;20 people with acute sore throat;13 patients three years of age or younger with pharyngitis;21 and patients with acute tonsillitis.18

Interventions and Comparators

In the RCT,19 patient management using an integrated clinical prediction rule based on the Walsh and Heckering clinical prediction rules was compared with patient management using usual care. Providers using the integrated clinical prediction rule were provided in-person, one-hour training. The observational study12 compared patient management before the implementation of a clinical decision rule using the McIsaac scoring and after the implementation of the rule.

Two guidelines18,21 reported on signs and symptoms, and culture test and rapid test; two guidelines15,20 reported on culture test and rapid test, one guideline13 reported on FeverPAIN score.

Outcomes

In the clinical studies, outcomes reported included culture test orders,12,19 rapid test orders,19 and antibiotic prescriptions.18,19

The guidelines presented recommendations regarding the diagnosis of bacterial infection for patients with pharyngitis,15,20,21 sore throat,13 and tonsillitis.18

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Critical appraisal of the studies is summarized below and details are available in Appendix 3, and .

In both the included clinical studies12,19 the objective was clearly stated, the patient characteristics and interventions were described and conflicts of interest were declared and there were no apparent issues. One study19 was a randomized study; randomization was done using a random number generator. The second study was a retrospective chart review hence systematic recording of data may not have occurred and potential for selection bias cannot be ruled out. For both studies12,19 it was unclear if a sample size calculation had been undertaken hence it was unclear if there was sufficient power to detect a meaningful difference. In the RCT it was unclear if there were any withdrawals and in the retrospective observational study it was unclear if all the patients were analyzed or if there were any exclusions of patients because of insufficient data recorded, hence impact of these on the findings is uncertain.

In all five guidelines13,15,18,20,21 the scope and purpose were clearly stated. In the NICE guideline13 details of the methodology used was not described and the evidence on which the recommendations were based was not described. However, the guideline13 was developed based on their guideline development manual, according to which the guideline development group comprises experts in the area as well as lay persons, conflicts of interest of the members are declared and resolved, a systematic literature search is undertaken, the best available evidence is used, resource implications are considered, the guideline is externally reviewed and a policy of updating is in place. In four guidelines15,18,20,21 the guideline development group comprised health care professionals in relevant areas and one guideline18 also included consumers. In four guidelines15,18,20,21 a systematic literature search was undertaken to identify relevant evidence. However, the evidence on which the recommendations were based was partially provided in two guidelines,15,18 and not provided in two guidelines.20,21 In four guidelines15,18,20,21 it was unclear if resource implications were considered and if a policy was in place for updating. In the absence of a policy for updating, it is difficult to determine if the guidelines still remain valid with the lapse of time. One guideline15 was externally reviewed and for three guidelines18,20,21 it was unclear if an external review had been undertaken. In one guideline21 recommendations were graded and in the other four guidelines13,15,18,20 recommendations were not graded.

Summary of Findings

Findings are summarized below and details are available in Appendix 4, and .

What is the clinical utility of clinical decision rules for the initial screening of patients with suspected group A strep infection?

One RCT19 showed that there was reduction in antibiotic prescribing, ordering of rapid streptococcal tests, and ordering of throat culture tests by providers in the integrated clinical decision rule group compared with providers in the usual care group. The reduction was statistically significant for rapid streptococcal testing, relative risk (RR) 0.75, (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.58 to 0.97) and also when the RR was calculated adjusting for age. However, the reductions were statistically significant for throat culture testing (RR, 0.55, [95% CI: 0.35 to 0.86]) but was no longer statistically significant when adjusted for age. Also, reduction in antibiotic prescribing was not statistically significant (RR 0.77, [95% CI: 0.53 to 1.11]). Of note, the mean age of patients who were treated by providers in the integrated clinical decision rule group was less than the mean age of patients treated by the providers in the usual care group.

One retrospective study12 showed that use of the McIsaac tool resulted in a decrease in unnecessary culture testing and antibiotic prescribing, in children with acute sore throat, at a hospital in Malaysia. In this study, a greater proportion of clinicians were found to be compliant with McIssac rule after enforcement of the McIssac rule than before enforcement of the rule, 68% versus 45%.

In summary, limited evidence suggests that use of a scoring tool, for initial identification of patients with GA strep infection, may reduce unnecessary additional testing and inappropriate antibiotic use; however the findings were not always statistically significant.

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the diagnosis of suspected group A strep infection?

The Hong Kong College of Pediatricians’ guideline,15 recommends testing for GA strep using a culture test or RADT, for children with acute sore throat, if signs and symptoms are suggestive of bacterial infection, age is greater than 3 years, or the patient is known to have GA strep contact. If otherwise, then no further testing or treatment is indicated.

The guideline developed by Harris et al.20 recommends that adult patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of GA strep pharyngitis should undergo RADT or culture tests for confirmation, and an antibiotic should only be prescribed for confirmed cases.

The NICE guidelines13 recommends antibiotic treatment be based on the FeverPAIN and Centor criteria. It was mentioned that FeverPAIN and Centor criteria are used in clinical practice and that it was preferable to use a scoring tool rather than not using any tool, recognizing that there was uncertainty regarding which tool is more effective in a UK population.

The UMHS Pharyngitis Guideline,21 recommends that clinical and epidemiological findings (i.e. signs and symptoms suggestive of GA Strep or signs and symptoms suggestive of viral etiology) should be considered before deciding on testing. Patients with signs and symptoms of viral etiology generally should not be tested for GA strep infection. Rapid strep tests should be reserved for patients with reasonable probability of GA strep infection and negative results should be confirmed by culture tests in patients younger than 16 years of age, due to their higher risk of acute rheumatic fever.

The guideline developed by Windfuhr et al.18 recommends that patients with tonsillitis should be assessed by McIsaac scoring tool and that scores of 3 or more warrant RADT or culture test for identifying beta-hemolytic streptococcus.

In summary, three guidelines15,20,21 which did not mention any specific clinical decision rule, recommend that if signs and symptoms were suggestive of bacterial infection then further testing should be undertaken. One guideline18 recommends the use of a clinical decision rule tool (McIsaac) to identify patients who warrant further testing. One guideline13 recommends the use of a clinical decision rule tool (FeverPAIN or Centor) to patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic treatment.

Limitations

There are several limitations.

There is limited evidence on the clinical utility of clinical decision rules. Two studies of variable quality examined the effect of the use of a clinical decision rule with respect to identifying appropriate patients for testing for GA strep or antibiotic prescribing. However, no information was identified with respect to clinical utilities such as the change in the duration of symptoms, the length of hospital stay or adverse effects. Long term effects, resulting from decisions based on initial screening using a decision rule, were unclear.

In one study12, which compared decisions with respect to ordering of culture tests or prescribing antibiotics before and after the enforcement of the McIsaac rule, the compliance of clinicians even after enforcement of the McIsaac rule was 68%. Hence the true effect of the use of the McIsaac rule could be not be determined.

Although in the guidelines, a systematic literature search appears to have been undertaken to identify evidence, details of the methodology were not presented; also the evidence on which the recommendations were based was not described or lacked details. The majority of the included guidelines did not mention if a policy was in place for updating the guidelines, hence the relevance of the guidelines with the lapse of time since publication, is unclear. The findings need to be interpreted in the light of limitations (such as lack of data on outcomes such as duration of symptoms, adverse effects, and long term effects; and lack of methodology details and evidence supporting recommendations were sparse).

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Seven relevant publications comprising one RCT,19 one retrospective observational study,12 and five guidelines.13,15,18,20,21 on clinical decision rules or strategies for identifying GA strep infection, were identified.

Limited evidence from studies of variable quality, suggests that use of a clinical decision rule tool, for initial identification of patients with GA strep infection, may reduce unnecessary additional testing and inappropriate antibiotic use; however the findings were not always statistically significant.

Some studies9,22–24 on clinical decision rule tools reported on their diagnostic accuracy parameters such as sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value and based on these parameters made predictions with respect to requirement for further testing or antibiotic prescription but did not actually investigate these outcomes, hence did not satisfy our inclusion criteria. One such study22 showed that the some clinical decision rules (McIsaac, Attia, Smeesters, and Joachim) performed reasonably well with respect to excluding GA strep pharyngitis in children but did not perform as well with respect to positive GA strep diagnosis. A second study23 reported that empiric antibiotic therapy based on a modified Centor score of 4, would result in unnecessary treatment of a substantial number of children with non-streptococcal pharyngitis. A third study24 mentioned that clinician judgement and Centor score were not adequate tools for making decisions with respect to children presenting with sore throat. A fourth study9 reported that the applicability of clinical decision rules for determining which children with pharyngitis should undergo a rapid detection test remains uncertain.

Three guidelines15,20,21 which did not mention any specific clinical decision rule tool, recommend that if signs and symptoms were suggestive of bacterial infection then further testing should be undertaken. The fourth guideline18 recommends the use of a clinical decision rule tool (McIsaac) to identify patients who warrant further testing. The fifth guideline13 recommends the use of a clinical decision rule tool (FeverPAIN or Centor) to identify patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic treatment.

The findings need to be interpreted in the light of limitations mentioned. Based on the evidence identified in this review, a definitive conclusion regarding the clinical utility of clinical decision rules for the initial screening of patients with suspected group A strep infection cannot be made. Additional studies examining the use of clinical decision rules as well as the patient outcomes, diagnostic testing, and antibiotic prescribing related to their use are required to make definitive conclusions

References

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

Cohen

JF, Bertille

N, Cohen

R, Chalumeau

M. Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016

Jul

4;7:CD010502. [

PMC free article: PMC6457926] [

PubMed: 27374000]

- 5.

- 6.

Sims

Sanyahumbi A, Colquhoun

S, Wyber

R, Carapetis

JR. Global disease burden of group A streptococcus. In: Ferretti

JJ, Stevens

DL, Fischetti

VA, editors. Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic biology to clinical manifestations [Internet]. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016 [cited 2018 May 10]. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343617/ [

PubMed: 26866208]

- 7.

- 8.

Cots

JM, Alos

JI, Barcena

M, Boleda

X, Canada

JL, Gomez

N, et al. Recommendations for management of acute pharyngitis in adults. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2015

May;66(3):159–70. [

PMC free article: PMC7124194] [

PubMed: 25772389]

- 9.

- 10.

Van Brusselen

D, Vlieghe

E, Schelstraete

P, De Meulder

F, Vandeputte

C, Garmyn

K, et al. Streptococcal pharyngitis in children: To treat or not to treat?

Eur J Pediatr. 2014

Oct;173(10):1275–83. [

PubMed: 25113742]

- 11.

- 12.

Thillaivanam

S, Amin

AM, Gopalakrishnan

S, Ibrahim

B. The effectiveness of the McIsaac clinical decision rule in the management of sore throat: An evaluation from a pediatrics ward. Pediatr Res. 2016;80(4):516–20. [

PubMed: 27331353]

- 13.

Sore throat (acute): Antimicrobial prescribing [Internet]. London (GB): National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2018

Jan. [cited 2018 May 9]. (NICE guideline; no. 84). Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84- 14.

- 15.

Chan

JYC, Yau

F, Cheng

F, Chan

D, Chan

B, Kwan

M. Practice recommendation for the management of acute pharyngitis. Hong Kong Journal of Paediatrics. 2015;20(3):156–62.

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

Windfuhr

JP, Toepfner

N, Steffen

G, Waldfahrer

F, Berner

R. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillitis I. Diagnostics and nonsurgical management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(4):973–87. [

PMC free article: PMC7087627] [

PubMed: 26755048]

- 19.

McGinn

TG, McCullagh

L, Kannry

J, Knaus

M, Sofianou

A, Wisnivesky

JP, et al. Efficacy of an evidence-based clinical decision support in primary care practices: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(17):1584–91. [

PubMed: 23896675]

- 20.

Harris

AM, Hicks

LA, Qaseem

A, High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Appropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infection in adults: Advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2016

Mar

15;164(6):425–34. [

PubMed: 26785402]

- 21.

- 22.

- 23.

Mazur

E, Bochynska

E, Juda

M, Koziol-Montewka

M. Empirical validation of Polish guidelines for the management of acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2014;78(1):102–6. [

PubMed: 24290006]

- 24.

Orda

U, Mitra

B, Orda

S, Fitzgerald

M, Gunnarsson

R, Rofe

G, et al. Point of care testing for group A streptococci in patients presenting with pharyngitis will improve appropriate antibiotic prescription. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2016;28(2):199–204. [

PubMed: 26934845]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Clinical Studies

View in own window

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Comparison | Outcome |

|---|

| Randomized controlled trial |

|---|

| McGinn,19 2013, USA | RCT

Primary care providers were randomized using a random number generator into two groups. Control group (usual care) and Intervention group (had one-hour training and introduction to a tool for clinical prediction)

Setting: two large urban ambulatory primary care practices at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York. Providers include physicians, residents, fellows, and nurse practitioners.

Intervention group (I): From 1 November 2010 to 31 October 2011, the EHR user access setting was modified so that the CPR tool was accessible to the Intervention group.

Control group (C): usual care in EHR environment | Characteristics of the provider groups (I and C) compared were not presented. However, it was stated that there were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the providers in the two groups. Total number of providers enrolled = 168

Characteristic of patient in the I and C groups: The patient population was diverse: 56% Hispanic, 35% African-American, 7% White, and 2% other.

Age (median (SD) (years): 43 (28) in I group, 49 (28) in C group (P = 0.001);

% Female: 23.9 in I group, 22.7 in C group (P = 0.67)

Race/ethinicity, smoking status or comorbidities of the patients were not statistically significantly different in the two provider groups.

Total number of visits for pharyngitis was 374 in I group and 224 in C group | Integrated clinical prediction rule [CPR] based on Walsh rule for streptococcal pharyngitis (a well-validated integrated CPR) was compared to usual care

Providers were invited to use the CPR risk score calculator and were provided management recommendations based on the score

CPR score:

Score = −1 indicates strep pharyngitis unlikely; recommendation to provide supportive care.

Score = 0 to 1 indicates intermediate risk of strep pharyngitis; recommendation for throat culture test or symptom resolution before deciding on antibiotics.

Score ≥ 2 indicates high risk of strep pharyngitis; recommendation to start empirical antibiotics. | Culture test ordered, RST ordered; antibiotic ordered; |

| Observational study |

|---|

| Thilloaivanam,12 2016, Malayasia | Retrospective study (bed head ticket review)

Setting: Hospital Kulim, Malaysia

Time: July to September 2012, before implementation of McIsaac rule; October to December, 2012, after implementation of McIsaac rule | Patients (children) with sore throat. Group A comprises patients who were treated before implementation of the McIsaac rule and Group B comprises patients who were treated after implementation of the McIsaac rule

N = 116 (60 in Group A, 56 in Group B)

Age (mean [SD]) (years): 4.12 (2.8) in Group A; 3.38 (3.03) in Group B; (P = 0.04).

Female: 53.3% in Group A; 50% in Group B; (P = 0.72).

Ethnicity and related medical history were comparable in both groups | Patient diagnosis and management by provider before and after implementation of McIsaac score were compared.

The suggested management strategies using McIsaac scoring are: for scores 0 or 1, no culture test or antibiotic is required; for scores 2 or 3, culture test for all and treat only if culture results are positive; and for score 4 or 5, treat with antibiotics on clinical grounds, without culture test. | Culture test ordered, antibiotics prescribed |

C = control group; CPR = clinical prediction rule; EHR = electronic health records; I = intervention group; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RST = rapid streptococcal test

Table 3Characteristics of Included Guidelines

View in own window

| First Author/Group, Year, Country | Objective | Guideline Development Group, Target Users | Methodology |

|---|

| Chan (Hong Kong College of Pediatricians),15 2015, Hong Kong | Objective was to provide practice recommendations for the management of acute pharyngitis | The GDG included pediatric infectious disease specialists, pediatric respirology specialists, and general pediatricians from both public hospitals and private sector.

Intended users: pediatricians and primary care physicians

Target population: pediatric patients with acute pharyngitis | Systematic literature search was conducted.

Method for evidence selection was not described.

Unclear if recommendations were formulated using consensus, voting or some other method

Recommendations were not graded. |

| Harris (for the High Value Care Task Force of ACP and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention),20 2016, USA | Objective was to provide best practices for antibiotic prescribing in generally healthy adults (i.e. without chronic lung disease or immunocompromising conditions) with acute respiratory tract infection. | GDG included clinicians

Intended users: clinicians involved in the care of adults seeking ambulatory care for acute upper respiratory tract infection.

Target population: adults with acute respiratory tract infections | Systematic literature search was conducted.

Method for evidence selection was not described.

Unclear if recommendations were formulated using consensus, voting or some other method.

Recommendations were not graded. |

| NICE guideline,13 2018, UK | Objective was to provide guidance on antimicrobial prescribing strategies for acute sore throat with the aim of limiting antibiotic use and reducing antimicrobial resistance | Composition of GDG was not specified but according to the guideline development manual experts in the relevant areas comprise the GDG

Intended users: Health professional; and people with acute sore throat and their families.

Target population: People with acute sore throat | Guideline development methodology was not specifically described but NICE guidelines are required to follow a systematic approach as described in the Guideline development manual (https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/chapter/introduction)

Unclear if recommendations were formulated using consensus, voting or some other method.

Recommendations were not graded. |

| UMHS Pharyngitis Guideline,21 2013, USA | Objective was to provide guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pharyngitis and for minimizing the risk of developing rheumatic fever and suppurative complications | GDG comprised individuals with expertise in pediatrics, internal medicine, family medicine, and medical education.

Intended users: appears to be clinicians but was not specified

Target population: Patients ≥ 3 years of age with pharyngitis. | Systematic literature search was conducted.

Guidelines were developed based on evidence from RCTs; if RCTs not available observational studies were considered; and if such evidence sources were unavailable then expert opinion was considered.

Unclear if recommendations were formulated using consensus, voting or some other method

Recommendations were categorized according to specific criteria |

| Windfuhr,18 2016, Germany | Objective was to provide clinicians in any setting with guidance on various conservative treatment options for reduction in inappropriate variation in clinical care, improvement in clinical outcomes and reduction in harms. | The GDG comprised individuals in the areas of pediatrics, pediatric infectiology, otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, and also consumers

Intended users: Clinicians in any setting.

Target population: patients with acute tonsillitis | Systematic literature search was conducted. An explicit and transparent protocol prepared a priori, was used to create actionable statements supported by relevant literature

Method for evidence selection was not described.

Recommendations were formulated using a Delphi procedure or in case of a consensus conference a formal consensus procedure was followed.

Recommendations were not graded. |

GDG = guideline development group; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCT = randomized controlled trial; UMHS = University of Michigan Health System

Table 4Grade of Recommendations and Level of Evidence for Guidelines

View in own window

| Grade of Recommendations | Strength of Evidence |

|---|

| Chan,15 2015, Hong Kong |

|---|

| Not reported | Not reported |

| Harris,20 2016, USA |

|---|

| Not reported | Not reported |

| NICE guideline,13 2018, UK |

|---|

| Not reported | Not reported |

| UMHS Pharyngitis Guideline,21 2013, USA |

|---|

“Strength of recommendation:

I = generally should be performed; II = may be reasonable to perform; III = generally should not be performed.” Page 1 | “Levels of evidence reflect the best available literature in support of an intervention or test:

A=randomized controlled trials; B=controlled trials, no randomization; C=observational trials; D=opinion of expert panel.” Page 1 |

| Windfuhr,18 2016, Germany |

|---|

| Not reported | Not reported |

NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; UMHS = University of Michigan Health System

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies using Downs and Black checklist16

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trial |

|---|

| McGinn,19 2013, USA |

|---|

The objective was clearly stated The inclusion and exclusion criteria were stated Patient characteristics in the two provider groups were described; intervention and outcomes were described. Randomization was done using a random number generator P-values were reported Conflicts of interest were declared. No apparent issues.

| Characteristics of the providers in the two groups being compared were not presented. However, it was stated that there were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the providers in the two groups. Unclear if sample size calculations were conducted Blinding of the provider was not possible. It was unclear if the patients were blinded Unclear if there were any withdrawals

|

| Observational study |

|---|

| Thillaivanam,12 2016, Malaysia |

|---|

The objective was clearly stated Patient characteristics, intervention and outcomes were described. P-values were reported Conflicts of interest were declared. No apparent issues.

| The inclusion and exclusion criteria were not stated Not randomized; a retrospective chart review Unclear if sample size calculations were conducted No blinding Unclear if all patients during the specified time were analyzed

|

Table 6Strengths and Limitations of Guidelines using AGREE II17

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Chan,15 2015, Hong Kong |

|---|

The scope and purpose were clearly stated. The guideline development group comprised pediatric infectious disease specialists, pediatric respirology specialists, and general pediatricians from both public hospitals and private sector. A systematic literature search was conducted but methodology with respect to study selection was not described Evidence on which the recommendations were based was provided in some instances The document was externally reviewed The authors mentioned that there were no conflicts of interest to declare

| Unclear if patient preferences were considered Unclear if resource implications were considered Unclear if a policy was in place for updating the guideline Recommendations were not graded

|

| Harris,20 2016, USA |

|---|

The scope and purpose were clearly stated. The guideline development group comprised clinicians. A systematic literature search was conducted but methodology with respect to study selection was not described. Conflicts of interest were declared, discussed and resolved

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not provided. Unclear if the document was externally reviewed. However, it was reviewed and approved by the High Value Task Force of ACP, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which comprised of clinicians trained in internal medicine and its sub-specialties and also including experts in evidence synthesis. Unclear if patient preferences were considered Unclear if resource implications were considered Unclear if a policy was in place for updating the guideline Recommendations were not graded

|

| NICE guideline,13 2018, UK |

|---|

| |

| UMHS Pharyngitis Guideline,21 2013, USA |

|---|

The scope and purpose were clearly stated. The guideline development group had expertise in relevant areas (clinical, and medical education) A systematic literature search was conducted but methodology with respect to study selection was not described Recommendations were graded. The document was reviewed by the departments and divisions of the University of Michigan Medical School. The authors appeared to have no potential conflicts of interest

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not provided Unclear if patient preferences were considered Unclear if resource implications were considered Unclear if the document was externally reviewed. It was mentioned that drafts of the guideline were reviewed at clinical conferences Unclear if a policy was in place for updating the guideline

|

| Windfuhr,18 2016, Germany |

|---|

The scope and purpose were clearly stated. The guideline development group comprised of individuals in the areas of pediatrics, pediatric infectiology, otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, and also consumers. A systematic literature search was undertaken. The authors mentioned that an explicit and transparent protocol prepared a priori was used to create actionable statements supported by relevant literature. Since consumers were included in the GDG, it is possible that patient preferences were considered. Potential conflicts of interest were compiled, discussed, and finally disclosed.

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not always described Recommendations were not graded Unclear if resource implications were considered. However there was some mention of comparative cost of RADT and culture test Unclear if the document was externally reviewed Unclear if a policy was in place for updating the guideline Potential conflicts of interest were required to be declared but it was unclear what action was taken to resolve any potential issues

|

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 7Summary of Findings of Included Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Author’s Conclusion |

|---|

| Randomized controlled trial |

|---|

| McGinn,19 2013, USA |

|---|

| Test and antibiotic orders in the Intervention (I) and Control (C) groups: | The authors stated that “The CPR is a form of complex CDS that holds great promise for reducing over treatment and testing.” Page 1589 |

|---|

| Outcome | Percentage of visits where test or antibiotic orders placed | RR (95% CI) | Age adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|

| I group (total visits = 374) | C group (total visits = 224) |

|---|

| Rapid streptococcus test ordered | 29.1 | 41.5 | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97) |

| Throat culture test ordered | 20.3 | 22.3 | 0.55 (0.35 to 0.86) | 0.54 (0.18 to 1.64) |

| Antibiotic ordereda | 15 | 19.6 | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.11) | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.10) |

Use of Integrated Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR) tool in the I group

Number of times the tool was opened = 278 (74.3%)

Number of times the risk prediction calculator (embedded in the tool) was opened = 249

Percentage of times the CPR tool was opened for patients with sore throat in various score categories:

for low score (−1 to 0): 55.4% (138/249),

for medium score (1 to 2): 37.3% (93/249),

for high score (3 to 4): 7.2% (18/249) |

| Observational Study |

|---|

| Thillaivanam,12 2016, Malaysia |

|---|

| Culture tests rate and antibiotic usage rate in children with sore throat in Hospital Kulim | The authors stated that “It can be concluded that the McIsaac rule is an effective tool in reducing misuse of antibiotics and redundant throat swab cultures in children diagnosed with sore throat in Malaysia.” Page 519 |

|---|

| Item | Before implementation of McIsaac rule | After implementation of McIsaac rule | P value |

|---|

| Group A (N = 60) | Group B (N = 56) |

|---|

| Number (%) of culture tests conducted | 20 (33.3) | 20 (35.7) | 0.79 |

| Number (%) of culture tests conducted which were redundant according to McIsaac rule | 8 (40) | 0 (0) | 0.003 |

| Number (%) of patients prescribed antibiotics | 54 (90) | 38 (67.9) | 0.007 |

| Number (%) of patients prescribed antibiotics not conforming to McIsaac rule | 32 (53.3) | 15 (26.8) | 0.003 |

| Clinician compliance to McIsaac rule | 27 (45) | 38 (67.9) | 0.0005 |

- a

An order is counted as a visit where at least one antibiotic order was placed

C = control; CI = confidence interval, CDS = clinical decision support; CPR = clinical prediction rule; I = intervention; RR = relative risk

Appendix 5. Recommendations

Table 8Recommendations and Supporting Evidence

View in own window

| Evidence | Recommendations |

|---|

| Chan,15 2015, Hong Kong |

|---|

It has been shown that the prevalence of GA strep pharyngitis is lower (10% to 14%) for children less than 3 years of age, compared to 37% for school-age children. (references cited)

Considering that RADT has a specificity around 95%, a positive RADT result indicates with reasonable certainty a GA strep infection and further confirmation with culture test may not be necessary to start antibiotic therapy (references cited).

Considering that RADT has variable sensitivity ranging from 70% to 90%, a negative RADT result warrants confirmation with culture test before GA strep infection can be ruled out. (references cited) | Diagnostic testing

“ |

| Harris,20 2016, USA |

|---|

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not described. Information from the IDSA 2012 guideline was used to formulate recommendations. | High Value Care Advice:

“Clinicians should test patients with symptoms suggestive of group A streptococcal pharyngitis (for example, persistent fevers, anterior cervical adenitis, and tonsillopharyngeal exudates or other appropriate combination of symptoms) by rapid antigen detection test and/or culture for group A Streptococcus. Clinicians should treat patients with antibiotics only if they have confirmed streptococcal pharyngitis.” Page430 |

| NICE guideline,13 2018, UK |

|---|

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not described. However, the NICE guidelines are prepared following a systematic approach as described in the manual (https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/chapter/introduction and https://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/developing-nice-guidelines-themanual.pdf) | “Use FeverPAIN or Centor criteria to identify people who are more likely to benefit from an antibiotic [….]” Page 5 of 25

“People who are unlikely to benefit from an antibiotic (FeverPAIN score of 0 or 1, or Centor score of 0, 1 or 2)” Page 5 of 25

“People who may be more likely to benefit from antibiotic (FeverPAIN score of 2 or 3)” Page 6 of 25

“People who are most likely to benefit from an antibiotic (FeverPAIN score of 4 or 5, or Centor score of 3 or 4)” Page 7 of 25

FeverPAIN and Centor are two clinical scoring tools and are described below:

“FeverPAIN criteriaFever (during previous 24 hours) Purulence (pus on tonsils) Attend rapidly (within 3 days after onset of symptoms) Severely Inflamed tonsils No cough or coryza (inflammation of mucus membranes in the nose)

Each of the FeverPAIN criteria score 1 point (maximum score of 5). Higher scores suggest more severe symptoms and likely bacterial (streptococcal) cause. A score of 0 or 1 is thought to be associated with a 13 to 18% likelihood of isolating streptococcus. A score of 2 or 3 is thought to be associated with a 34 to 40% likelihood of isolating streptococcus. A score of 4 or 5 is thought to be associated with a 62 to 65% likelihood of isolating streptococcus.

Centor criteriaEach of the Centor criteria score 1 point (maximum score of 4). A score of 0, 1 or 2 is thought to be associated with a 3 to 17% likelihood of isolating streptococcus. A score of 3 or 4 is thought to be associated with a 32 to 56% likelihood of isolating streptococcus.” Page 24 of 25 |

| UMHS Pharyngitis Guideline,21 2013, USA |

|---|

| Evidence on which the recommendations were based was not described. However, levels of evidence and strength of recommendations were indicated | “Diagnosis.Signs/symptoms of severe sore throat, fever, tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, red pharynx with tonsillar swelling +/− exudate, and no cough indicate a higher probability of GAS pharyngitis for both adults and children. Algorithms of epidemiologic and clinical factors improve diagnosis by identifying patients with an exceedingly low risk of GAS infection [C*].” Laboratory confirmation:- -

Neither culture nor rapid antigen screen differentiate individuals with GAS pharyngitis from GAS carriers with an intercurrent viral pharyngitis.” - -

Consider clinical and epidemiological findings […..] when deciding to perform a microbiological test. [IB*].” - -

Patients with manifestations highly suggestive of a viral infection such as coryza, scleral conjunctival inflammation, hoarseness, cough, discrete ulcerative lesions, or diarrhea, are unlikely to have GAS infection and generally should NOT be tested for GAS infection [IIB*].”

Throat culture is the presumed “gold standard” for diagnosis. Rapid streptococcal antigen tests identify GAS more rapidly, but have variable sensitivity [B*].- -

Reserve rapid strep tests for patients with a reasonable probability of having GAS.” - -

Confirm negative screen results by culture in patients < 16 years old (& consider in parents/siblings of school age children) due to their higher risk of acute rheumatic fever [IIC*].” - -

If screening for GAS in very low risk patients is desired, culture alone is cost-effective [IIC*].” Page 1

|

| Windfuhr,18 2016, Germany |

|---|

The McIsaac scoring tool corrects for age, and can be used for both adults and children (references cited).

RADT or culture test should be considered for patients with Centor or McIsaac score of ≥ 3 but not for patients with score ≤ 2, unless there is persistent illness. (references cited)

Evidence on which the recommendations were based, was not always described. | “For differentiation of viral tonsillitis and tonsillitis caused by β-hemolytic streptococci, the assessment should be performed based on a diagnostic scoring system (modified Centor Score / McIsaac Score). If therapy is considered, a positive score of ≥ 3 should lead to pharyngeal swab for rapid antigen detection or culture in order to identify β-hemolytic streptococci. Routinely performed blood tests with regard to acute tonsillitis are not indicated. After acute streptococcal tonsillitis, there is no need for routine follow-up examinations of pharyngeal swab. After acute streptococcal tonsillitis, routine blood tests or urine examinations or cardiologic diagnostics such as ECG are not indicated.” Page 976

|

GAS = G A streptococcus; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RADT = rapid antigen detection test; UMHS = University of Michigan Health System

- *

“Strength of recommendation:

I = generally should be performed; II = may be reasonable to perform; III = generally should not be performed.

Levels of evidence reflect the best available literature in support of an intervention or test:

A=randomized controlled trials; B=controlled trials, no randomization; C=observational trials; D=opinion of expert panel.” Page 1

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Clinical Decision Rules and Strategies for the Diagnosis of Group A Streptococcal Infection: A Review of Clinical Utility and Guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.