Meal Delivery Programs for Community Seniors: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Authors

Casey Gray and Charlene Argáez.Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- DDM

daily delivered meals

- EQ-5D-3L

EuroQoL Group-5 dimension-3 level questionnaire

- EQ-VAS

EuroQoL Group visual analogue scale

- GARS

Groningen activity restriction scale

- GQoL

global quality of life

- HRQoL

health related quality of life

- IQR

interquartile ratio

- Kg/m2

kilogram per square metre

- MD

meal delivery

- n

sample size

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SD

standard deviation

- T1

baseline

- T2

first follow-up

- T3

second follow-up

- UCLA

University of California Las Angeles

- WDM

weekly delivered meals

- WHO-5

World Health Organization 5-Item Well-Being Index

Context and Policy Issues

The proportion of older adults in Canada has been growing steadily since the 1970s.1 In 1986, older adults (aged ≥65 years) made up 10% of the Canadian population.2 By 2016, 16.5% of Canadians were aged 65 years and older and 13% (of those 65 and older) were aged 85 or older.3 Generally, the health status of older adults indicates Canadians are living longer and are healthier than those from previous generations.4 However, it has been raised that the health care system will not be able to meet the health care needs of Canada’s growing population of older adults.4

Canada’s Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors included social connectedness and healthy eating among five key areas of focus in 2005.5 Social connectedness can become an issue when older adults lose a spouse or co-resident. This can lead to feelings of isolation and reduced well-being.5 Loss of a spouse or co-resident can also affect the financial status of older adults.5 Taken together with physical health declines, nutrition needs can become an issue. While 41% of older adults rate their own health as very good or excellent,4 age can be accompanied by challenges in the ability to carry out activities of daily living like eating and functional activities such as preparing food, as well as increasing chronic health concerns.4

Nevertheless, most adults aged 55 years or older want to remain in their homes as they age, and most older adults (93%) have remained living in private households.4 To remain in their homes, some older adults require support.4 A 2011 CADTH environmental scan of initiatives for healthy aging underway in Canada indicated that supporting older adults to remain in community is an important target of interventions.6

Related to this review, a previous CADTH rapid response review on the clinical effectiveness of congregate meal programs for older adults living in the community did not identify any relevant studies.7 The purpose of the current report is to review the clinical effectiveness of meal-delivery nutrition programs for older adults living in the community.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of meal delivery nutrition programs for older adults living in the community?

Key Findings

One randomized controlled trial (RCT) and two non-randomized studies were identified regarding the clinical effectiveness of meal delivery nutrition programs for community-dwelling older adults. Low quality evidence from one RCT and one single-arm non-randomized study showed that meal delivery nutrition programs may improve loneliness among older adults. The same single-arm study showed a positive association between meal delivery nutrition programs and self-reported well-being. Frequency of meal delivery does not appear to be a factor. Low quality evidence from one controlled non-randomized study showed that a meal delivery nutrition program was not associated with perceived improvement in quality of life among community-dwelling older adults. No evidence regarding independence or other mental health or psychosocial outcomes was identified.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. No methodological filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2008 and December 17, 2018.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Selection Criteria.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in Table 1, they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2008.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included randomized studies were critically appraised by one reviewer using the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Studies (RoB 2),8 and non-randomized studies were critically appraised using the Downs and Black Checklist.9 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

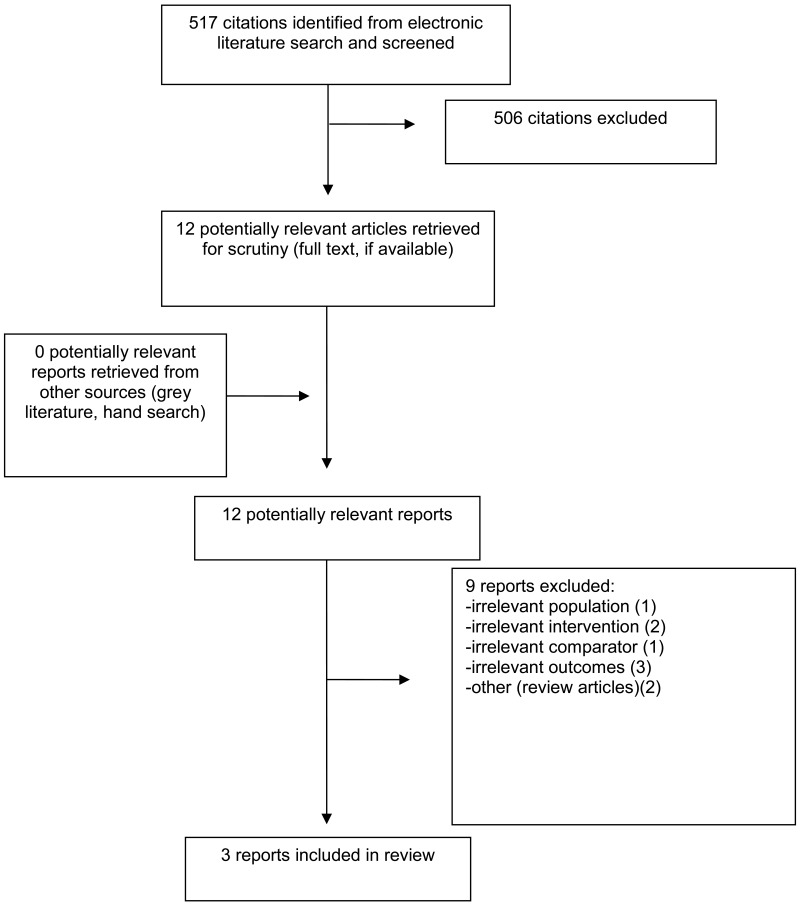

A total of 517 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 505 citations were excluded and 12 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of the potentially relevant articles, nine publications were excluded for various reasons, and three publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised one RCT and two non-randomized studies. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA10 flowchart of the study selection.

Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Three clinical studies were identified for inclusion in this report.11,12 One three-arm, parallel, unblended pragmatic RCT that was published in 2016 was identified. Investigators of the RCT recruited older adults (not defined) from waitlists for home meal delivery at eight Meals-On-Wheels America sites between the winter of 2013 and spring of 2014. Participants were randomized to one of three arms and there was no mention of allocation concealment.12

One two-arm, non-randomized controlled trial published in 201711 and one single-arm before-and-after study published in 201513 were identified. The controlled study recruited home-dwelling older adults with functional disability who were clients of a home care organization.11 Nurses from the organization screened all clients for eligibility and invited those eligible to participate in the study.11 The single-arm study was less strict and did not limit participants to those with functional disability.13 The program intake coordinator screened participants for eligibility as they enrolled in the meal delivery program and invited those eligible to participate.13 Participants of the non-randomized studies were recruited between November 2013 and April 2014.11,13

Country of Origin

The included RCT was conducted in the US12 and the non-randomized studies were conducted in the US13 and the Netherlands.11

Patient Population

Participants in the clinical studies were older adults living in the community.11–13 In the RCT, authors reported open eligibility as this was a pragmatic study. Participants were 376 Meals-on-Wheels waitlisted customers at one of the eight participating sites and were home-bound (not defined) older adults.12 There were no differences between groups for most baseline characteristics assessed at baseline.12 Mean ages ranged from 75.7 to 77.4 years across groups, participants’ self-ratings of loneliness did not differ across groups (scores ranged from 3.1 to 3.5 out of 9).12 However, a significantly greater proportion of participants in the waitlist group were married (31.5% of the comparator vs. 18.9% and 21.9% in the intervention groups) and reported participating in groups (e.g., seniors centre, community group, public service) (34.9% of the comparator vs. 22.5% and 21.7% of the intervention, both P values < 0.05.12

Participants in the controlled non-randomized study were eligible if they were not able to prepare their own healthy meals as a result of functional impairment.11 Those with a partner at home were eligible if their partner was not able to prepare meals for them.11 Participants were excluded if they had problems with chewing, had severe malnutrition, had cancer or another serious condition, or had a life expectancy of < 6 months.11 Participants in the single-arm trial were not required to have functional disability and inclusion was quite broad.13 There were a total of 44 participants in the two-arm study and 62 in the single-arm study.11,13 Participants mean ages ranged from 74.11 to 84 years.11,13 Most participants in both studies were female (66% to 78.9%).11,13 In the controlled study, most participants did not live with a partner (intervention, 72% and control, 84.2%),11 and were receiving home care visits for assistance with self-care and medical tasks for an average of 5.6 (intervention) and 4.1 (control) hours per week.11 Participant self-reports of disability (mean of disability in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living) were 44.1 (intervention) and 40.6 (control), where higher scores reflect greater activity restriction.11 At baseline, 36% of intervention participants and 47.4% of participants in the control group were already receiving a meal delivery service; control group participants were able to continue receiving their meals from the other service through the duration of the intervention period.11 Details on cohabitation, disability, and previous meal delivery service were not collected in the single-arm study.13

Interventions and Comparators

There were two intervention conditions in the RCT and one control group.12 The interventions both consisted of 15 weeks of home meal delivery by program staff or volunteers.12 In the daily delivered meals condition, hot or chilled prepared meals (never frozen) were delivered once per day on week days (five days per week).12 In the weekly delivered meals condition, five frozen meals were delivered once per week.12 The comparator consisted of waitlist only.12

Intervention duration ranged from two13 to three11 months in the non-randomized studies. Both interventions consisted of a single meal delivered once daily on at least four days per week.11,13 Participants in the controlled trial were given a simple, portable convection oven to re-heat meals, which was intended to improve taste compared with microwave.11 The comparator in the controlled trial consisted of usual diet, which may have included use of an alternate meal delivery service.11

Outcomes

Loneliness was assessed in the RCT and single-arm non-randomized study.12,13 In the RCT, loneliness was assessed at baseline and 15-week follow-up using the 3-item University of California, Las Angeles (UCLA) Scale.12 Responses were selected on a scale ranging from 0 to 3, and summed. Potential overall scores range from 0 to 9, with higher scores reflecting greater feelings of loneliness.12 The scale had acceptable reliability. Scale validity and minimal clinically important difference were not reported.12 In the single-arm non-randomized study,13 loneliness was assessed at baseline and two-month follow-up using the 3-item Loneliness Scale.13 Responses were recording on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often) and summed.13 Potential overall scores ranged from 3 (no social isolation) to 12 (worse levels of loneliness).13 Measurement properties were not reported.13

Well-being was assessed in the single-arm non-randomized study using the World Health Organization 5-item questionnaire (WHO-5).13 Responses were recorded on a scale ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all the time).13 Summed scores ranged from 0 (worst possible) to 25 (good).13 Measurement properties were not reported.13

Quality of Life (QoL) was assessed in the controlled non-randomized study as health-related QoL and Global QoL.11 Health-related QoL was assessed with the EuroQoL visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS), a subscale of the EQ 5-dimension, 3-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L).11 Participants rated their current health state from 0 to 100 (worst- to best-imaginable health state).11 Measurement properties and minimal clinically important difference were not reported.11 Global QoL was assessed with the overall valuation of life subscale of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist.11 Participants rated how well they felt during the past week on a scale ranging from 0 to 6 (very bad to very good).11 Scores were transformed to a 100-point scale, with higher scores reflecting better global QoL.11 Measurement properties and minimal clinically important difference were not reported.11

Summary of Critical Appraisal

The critical appraisal of the included clinical studies is summarized here. Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 5.

Randomized Study

The randomized study was assessed using the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Studies.8 Several strengths and limitations were identified. Strengths included few deviations from the intended interventions and use of an outcome measure that has demonstrated acceptable reliability in previous research. There were also several important limitations. For example, although authors describe the study as an RCT, it seems unlikely that participants were actually randomly assigned to conditions, elevating the risk of selection bias. Authors described alphabetizing participant last names and assigning them to the three groups in sequential order. Although alphabetizing is associated with less bias than many methods, it may have been possible to predict group assignment. The risk of selection bias may have been further elevated, as it is unknown if allocation concealment took place. Finally, there was high risk of bias due to measurement of the loneliness outcome. Participants and outcome assessors were not blinded to intervention assignment. Participants were selected from a waitlist of potential future clients who wished to receive home delivered meals. Loneliness is a subjective outcome for which responses could reasonably be assumed to be at risk of bias if participants felt their ability to continue with the service- or gain access to the service at the conclusion of the study would be influenced. For example, waitlisted participants may have reported higher levels of loneliness if they believed doing so would lead to being prioritized for the service. In contrast, intervention recipients may have reported reduced loneliness as a means of emphasizing their gratitude and desire to continue receiving the service.

Non-Randomized Study

The non-randomized studies11,13 were assessed using the Downs and Black Checklist9 and several strengths and limitations were identified. First, it was considered a strength that the study characteristics, main findings, and funding sources were all clearly reported in the controlled study.11 Reporting was less clear in the single arm study, where main outcomes were described differently throughout the manuscript and funding sources were not disclosed.13

Regarding external validity, it was a strength of both non-randomized studies that all eligible participants within the participating organization or region were invited to participate.11,13 Nonetheless, this may still be considered a convenience sampling strategy. Furthermore, only 27% of eligible participants in the controlled study consented to participate,11 and it is unclear whether participants were representative of the entire population and therefore, whether findings generalize to the population from which the sample was drawn. It is unclear how many potential participants were approached to participate, raising similar issues.13 In terms of internal validity, the controlled study11 appears to have been generally well conducted. However, blinding did not take place, reducing our certainty that participant responses to questionnaires and analysis of data were not biased. There is a low likelihood that selection bias was an issue. Although participants were not randomized to intervention or control groups, baseline characteristics were similar between groups and potential confounders were examined and found not to be a factor during analysis.11 The exclusion of participants lost to follow-up from analyses further reducing our certainty that study findings can be generalized to the entire population being examined. An important limitation pertains to the instructions to those in the comparator condition regarding following their usual diet. Many participants were already using a meal-delivery service at the time of baseline assessments. Intervention participants were instructed to stop the other meal delivery service, while control group participants were invited to continue.11 This affected nine participants (47.4%) in the control group.11 It is unclear how the various meal-delivery services would have been run, and to what extent face-to-face socialization time would have differed between groups. The continuance of home meal delivery in the control group could have hidden or reduced the magnitude of any differences in outcomes between the intervention and control groups.

Summary of Findings

Clinical Effectiveness of Meal Delivery Nutrition Programs

Loneliness

Loneliness was examined in one RCT12 and one non-randomized study.13 In the RCT, after the 15 week intervention period, the waitlist comparator group reported higher loneliness than the combined daily and weekly meal delivery group when baseline loneliness scores were adjusted for (P = 0.018).12 Adjusted loneliness scores did not differ significantly between daily and weekly meal delivery groups (P = 0.359).12 Study authors concluded that home-delivered meals reduce feelings of loneliness in older adults.12 Consistent with this finding, loneliness scores were significantly reduced from baseline to follow-up in the non-randomized single arm study.13

Well-Being

Wellbeing was examined in one single-arm non-randomized study. After a two-month intervention, well-being was significantly improved.13

Quality of Life

QoL was examined in one non-randomized study as health-related and global QoL.11 After a three month intervention, there was no difference in health related QoL between the intervention and comparator groups immediately following the intervention (three-month follow-up) or three months later (six-month follow-up).11 Similarly, there was no difference in global QoL at three-month follow-up.11 However, there was a statistically significant difference between intervention and comparator in the change from baseline to 6 month follow-up, favouring the comparator group (P = 0.003).11 Authors concluded there were no favourable QoL effects of a three-month high-quality home delivered meal service for functionally disabled older adults living in community.11

Appendix 4 presents a table of the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations of the current body of evidence. To begin with, each study featured a relatively short intervention period (ranged from two to three months). It would be useful to know if greater improvements would be seen over time as participants remain in a home meal-delivery program. Second, no information was provided regarding the interaction between the delivery person and the meal recipient. Finally, while the included studies provide information about QoL, well-being, and loneliness, they do not provide any information about the effect of meal delivery nutrition programs on independence or other mental and social health outcomes.

The findings of this report may be generalizable to the Canadian context and provide useful information for policy makers about the utility of offering a meal delivery nutrition service to older adults living in the community in this country.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

One RCT and two non-randomized studies were identified to address the effectiveness of meal delivery nutrition programs for older adults living in the community. Overall, findings suggest receiving home-meal delivery for two to three months was associated with reduced feelings of loneliness, improved well-being and was not related to QoL. It is possible the short intervention period was not sufficient to change participant ratings of QoL.

Conclusions are tenuous due to being based on a small number of included studies, with small sample sizes, and data collected using outcome assessment tools for which there was a lack of information about the measurement properties. It is unclear whether improvements in loneliness ratings were clinically meaningful, as this information was not provided. Given that the control condition in the RCT was permitted to continue with another meal delivery service if one was being used, it is important to determine the benefits of meal delivery against no-meal delivery. Further research comparing meal delivery nutrition programs against not receiving meal delivery or versus other nutrition program comparators may help to reduce uncertainty.

References

- 1.

- Statistics Canada. Seniors. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2011.

- 2.

- Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada, population estimates 1971-2010. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2010.

- 3.

- Statistics Canada. Canada at a glance 2017: population. 2017; https://www150

.statcan .gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x /2017000/pop-eng.htm. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. - 4.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health care in Canada, 2011: a focus on seniors and aging. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2011: https://secure

.cihi.ca /free_products/HCIC _2011_seniors_report_en.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. - 5.

- Healthy Aging and Wellness Working Group of the Federal/Provincial/Territorial (F/P/T) Committee of Officials (Seniors). Healthy aging in Canada: a new vision, a vital investment from evidence to action. 2006: https://www

.health.gov .bc.ca/library/publications /year/2006/Healthy _Aging_A_Vital _latest_copy_October_2006.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. - 6.

- Ndegwa S. Initiatives for healthy aging in Canada. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2011: https://www

.cadth.ca /media/pdf/Initiatives _on_Healthy_Aging_in_Canada_es-17_e .pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. - 7.

- Banerjee S, Loshak H. Congregate meal programs for older adults living in the community: a review of clinical effectiveness. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2019: https://www

.cadth.ca /sites/default/files /pdf/htis/2019/RC1055 %20Congregate%20Meal %20Programs%20for%20Seniors%20Final.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. [PubMed: 31095352] - 8.

- Higgins JPT, Sterne JA, Savovic J, Page M, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I. Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(Suppl 1).

- 9.

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pmc/articles /PMC1756728/pdf/v052p00377.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 14. [PMC free article: PMC1756728] [PubMed: 9764259] - 10.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [PubMed: 19631507]

- 11.

- Denissen KF, Janssen LM, Eussen SJ, et al. Delivery of nutritious meals to elderly receiving home care: feasibility and efectiveness. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(4):370–380. [PubMed: 28346563]

- 12.

- Thomas KS, Akobundu U, Dosa D. More than a meal? A randomized control trial comparing the effects of home-delivered meals programs on participants’ feelings of loneliness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(6):1049–1058. [PubMed: 26613620]

- 13.

- Wright L, Vance L, Sudduth C, Epps JB. The Impact of a home-delivered meal program on nutritional risk, dietary intake, food security, loneliness, and social well-being. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;34(2):218–227. [PubMed: 26106989]

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2

Characteristics of Included Primary3 Clinical Studies.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3

Strengths and Limitations of RCT using Cochrane RoB 2.

Table 4

Strengths and Limitations of Non-Randomized Studies using Downs and Black Checklist.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 5

Summary of Findings of Included Primary Clinical Studies.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Other Outcomes

- Thomas KS, Parikh RB, Zullo AR, Dosa D. Home-delivered meals and risk of self-reported falls: results from a randomized trial. J Appl Gerontol. 2018 Jan;37(1):41–57. [PMC free article: PMC6620777] [PubMed: 27798291]

About the Series

Version: 1.0

Suggested citation:

Meal delivery programs for community seniors. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Jan. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.

The copyright and other intellectual property rights in this document are owned by CADTH and its licensors. These rights are protected by the Canadian Copyright Act and other national and international laws and agreements. Users are permitted to make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes only, provided it is not modified when reproduced and appropriate credit is given to CADTH and its licensors.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/