Copyright © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Jones F, Gombert-Waldron K, Honey S, et al. Using co-production to increase activity in acute stroke units: the CREATE mixed-methods study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2020 Aug. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 8.35.)

Parts of this chapter are based on Clarke et al.16 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Design and conceptual framework

Our evaluation used a mixed-methods, case comparison design. We conceptualised the development and implementation of the co-produced interventions as an organisational and social process involving interaction between the creators and the users of knowledge. Translating the knowledge arising from health services research into practice through the implementation of service innovations remains a key challenge in the drive to improve the quality of health care. Organisational and social processes will largely determine whether or not service improvements to patient, family and staff experiences are implemented in practice. Although frameworks have become increasingly sophisticated, the influence of context has not been fully accounted for in these models.66

Our aim was to evaluate the feasibility and impact of patients, carers and clinicians co-producing and implementing interventions to increase supervised and independent therapeutic patient activity in acute stroke units. We were particularly interested in the processes by which co-designed improvements are implemented in particular contexts and settings, and whether or not this process could be enhanced. We aimed to study both the impact of the improvements designed to increase activity and the feasibility of using EBCD in stroke units for the first time and the experiences of staff, patients and families taking part. We used normalisation process theory (NPT) to study the implementation and assimilation of the co-produced interventions in the local context of our study settings.67,68

The evaluation team consisted of researchers based at each site (FJ, KGW, DC and SH) who were supported by the wider project group (AM, GR, RH, CM and GC). The site researchers were responsible for all data collection. Analysis and interpretation were shared by the whole group. During phases 2 and 3, researchers were regularly present on the stroke units and attended staff meetings, handovers and training sessions to engage staff in the project and communicate with stroke unit-based clinical staff during pre and post data collection.

We used multiple data collection methods to generate quantitative and qualitative data to address the project’s research questions:

- What is known about the efficacy and effectiveness of co-production approaches in acute health care?

- How do patients and carers experience the use of a co-production approach and what impact does it have on quality and supervised and independent therapeutic activity on a stroke unit?

- How do staff from acute stroke units experience the use of a co-production approach and what improvements in supervised and independent therapeutic activities does the approach stimulate?

- How feasible is it to adopt EBCD as a particular form of co-production for improving the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

- What role can patients and carers have in improving implementation of National Clinical Guideline recommendations on the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

- What are the factors and organisational processes that act as either barriers to or facilitators of successfully implementing, embedding and sustaining co-produced quality improvements in acute care settings, and how can these be addressed and enhanced?

Question 1 was answered in a rapid evidence synthesis published in 2017.16 We anticipated that the findings would inform intervention phases and highlight the gaps in existing studies that could be addressed through our project phases. The aim was to identify and appraise reported outcomes of co-production as an intervention to improve the quality of services in acute health-care settings.

There are no agreed international guidelines for designing and conducting a rapid evidence synthesis. However, there is overall agreement that the process should involve providing an overview of existing research on a defined topic area, together with a synthesis of the evidence provided by these studies to address specific review questions. Rapid evidence syntheses are typically completed in 2–6 months, which does not normally allow for all stages of traditional effectiveness reviews. The rapid evidence synthesis was conducted between January and June 2016. The search terms used were specific to the use of co-production in acute health-care settings (see Appendix 8). To keep the search focused on co-production approaches, we omitted broader search terms, including co-operative behaviour, patient participation, collaborative approach and service improvement.

Database searches were conducted for the period 1 January 2005 to 31 January 2016. Given that two more general reviews relating to co-production had been published previously,7,18 and given the CREATE study focus, we reviewed post-2005 evidence and only that reporting on studies in acute health-care settings. We completed citation tracking of five seminal papers; in addition, five experts in co-production were requested to nominate three to five seminal papers relevant to our review.

The databases searched and the inclusion and exclusion criteria are given in Appendix 8 and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram and checklist for the rapid evidence synthesis are in Report Supplementary Material 5.

Screening

Two reviewers independently read all titles and abstracts. Differences in retain or reject decisions were discussed by the two reviewers, with the involvement of a third reviewer when consensus could not be reached. Three reviewers independently read the included full-text papers; decisions to retain or reject were made independently based on the inclusion criteria. All three reviewers then reached a consensus on retain or reject recommendations. The same three reviewers completed data extraction. The quality appraisal checklists developed by NICE for quantitative and qualitative studies were used. These address 14 areas of study quality ranging from theoretical approach to study design, data collection and analysis methods and ethics review. Two reviewers undertook data extraction and quality appraisal independently for each study. We did not exclude studies on the basis of quality appraisal, including all studies in the synthesis to inform discussion of the evidence identified. A mixed research synthesis approach was used. Studies were grouped for synthesis not by methods (i.e. qualitative and quantitative) but by findings viewed as answering the same research questions, or addressing the same aspects of a target phenomenon.

Our main evaluation focused on research questions 2–6.

Prior considerations

During project set-up and commencement, we recognised that the term ‘rehabilitation’ as used in our original application can be misleading and is often interpreted by patients as treatment delivered by a therapist. In the CREATE study we focused on supervised or independent social, cognitive and physical activity undertaken by patients and occurring outside one-to-one therapy sessions. We used an umbrella term of ‘activity’ for anything that patients do with or without help, however small, outside an individual one-to-one scheduled session of therapy. This could also include ‘clinical’ or ‘daily living’ activities, such as walking assisted/unassisted to the bathroom or getting dressed, and talking to other patients or to staff.

Of note is that the ethnographic observations and semistructured interviews conducted with patients and carers and staff pre and post completion of the EBCD cycles were used both to inform the EBCD process and as part of our evaluation. Prior to the introduction of EBCD, data generated using these methods enabled the research team to develop an understanding of what was occurring at those points in time and what activity was wanted going forward, and of staff members’, patients’ and carers’ experiences in these stroke units. Post the EBCD cycles, these data enabled the research team to develop an understanding of staff members’, patients’ and carers’ experiences of the EBCD process and their perspectives on the changes designed and implemented to increase social, cognitive and physical activity opportunities in these four stroke units. An overview of our data collection methods and whether the methods were used for evaluation, EBCD or both is provided in Table 3.

Procedure and participants

The observations and the interviews were conducted with patients and carers and staff pre and post completion of the EBCD cycles. Behavioural mapping was carried out with patients who were present on the stroke unit and able to provide informed consent the day before data collection. Interviews with staff across all specialties and grades took place after observations had been completed (pre and post EBCD) in each site.

Patients’ interviews took place within 3–6 months of their discharge from the stroke unit, when enough time had passed for adaptation to life at home to have begun, but soon enough after their inpatient care episode to allow reasonably accurate recall. Family members were recruited at the same time as patients. PROMs and PREMs combined in a single questionnaire pack (see Table 3) were sent to all patients discharged from each stroke unit in the 6 months prior to data collection in the pre-EBCD period and all those cared for during the EBCD/intervention period at each site.

Sampling and recruitment

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit participants who reflected the population of stroke patients admitted and discharged from our sites, who would naturally include patients with different levels of stroke severity, gender, age and ethnicity. We also aimed to include participants who had communication and/or cognitive impairments in order to reflect the stroke population, and encouraged family members to provide support when patients were unable to complete the questionnaires or take part in interviews. Several strategies were used to estimate our target numbers for recruitment.

Based on stroke admission data across London and Yorkshire, we estimated that it would be possible to collect PROM/PREM data from an independent sample of 30 patients from each unit pre and post implementation of co-produced interventions.

Behavioural mapping data collection took place during non-consecutive days. We aimed to recruit a minimum of four and a maximum of eight patients who met the inclusion criteria and were able to provide consent on the day before the observation.

Pre implementation of EBCD cycles, we aimed to purposively recruit a sample of approximately 10–15 staff, stroke participants and family carer members (30–45 in total from each unit) to take part in interviews as part of the co-design process. Stroke participants and family members or friends (carers) were also recruited 3–6 months after discharge from the stroke unit to allow time for adaptation to life at home to begin, but sufficiently soon after their inpatient care episode to allow reasonably accurate recall.

Post implementation of EBCD cycles, we aimed to recruit a further sample of up to 10 members of staff/patients and carers in each of the four sites to participate in semistructured interviews to explore their experiences post implementation of co-designed interventions. We also aimed to carry out interviews with a sample of staff members, patients and families who took part in the co-design groups to explore their experiences of being part of the whole process. The size of the sample was also informed by reaching thematic saturation during data analysis.

Sampling technique

- Convenience sampling was used to collect PROM/PREM data from consecutive patients and family/carer members discharged from participating stroke units over a 3- to 6-month period.

- Purposive sampling was used for behavioural mapping to ensure that recruited participants included those with different levels of stroke severity and those with aphasia (who are often excluded from stroke research).

- Purposive sampling was also used to recruit staff who worked on the participating stroke units. To ensure that a broad range of views were accommodated, we aimed to recruit staff from different grades and professional groups. In recruiting patients/families, we included those with experiences that varied according to the severity and range of impairment, as well as those stroke patients who may not have family members.

Data collection methods

Evaluation data collection took place pre and post implementation across all four sites. Table 3 shows the timings of data collection and the methods used:

- Semistructured interviews with patients and carers were carried out to elicit their perceptions and recall of opportunities for and experiences of activity in the stroke units. Patients from each unit were interviewed post discharge, and (at sites 1 and 2) in the pre-implementation stage these interviews were filmed. Topic guides for all of the interviews are in Appendices 2–5.

- Semistructured interviews with staff were carried out with staff with a range of stroke unit experience, from PTs, OTs and speech and language therapists, to nurses, doctors, psychologists, dietitians and support workers, at different grades, to elicit their perceptions of the stroke unit and the opportunities for and experiences of patient activity. In addition, staff perceptions of organisational processes that influenced activity with patients, carers and other members of the stroke team were explored, together with their views on areas in which additional supervised and independent therapeutic activity could be enhanced.

- PROMs and PREMs were sent to more than 60 patients cared for in each unit in the 6 months pre and post implementation (and cared for during the EBCD period). These measures are postal self-completed measures previously developed, reviewed and agreed in consultation with experienced stroke clinicians in West Yorkshire as part of the Clinical Information Management System for Stroke study [a Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health and Care (CLAHRC) project]. The measures allow a carer or a family member to record responses for a patient, if necessary, and were used successfully with patients after stroke in the Clinical Information Management System for Stroke study. The PROM incorporates validated measures including the Oxford Handicap Scale, the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). The PREM was developed by Kneebone et al.69 and is a validated tool for patient-reported experience of neurological rehabilitation.

- Non-participant observations (ethnographic fieldwork) in each stroke unit took place pre and post implementation. An observational framework developed for use in a previous process evaluation of caregiver training70 was used to record observations of the stroke unit contexts, organisational processes, staff and patient interactions and instances of planned and unplanned activity, including noting when timetabled therapy was occurring on a one-to-one or group basis (see Appendix 6). Observations, typically of 4–5 hours each, took place across 10 days at different times of the day, evenings and at weekends in order to develop understanding of how activity may vary across a range of times and days of the week.

- Behavioural mapping was used to record any social, cognitive or physical activity. These data were generated to establish an indication of activity levels in each unit at a given time point before and after the EBCD cycle was implemented. The data were from separate groups of patients; thus, we did not seek to compare ‘before and after’ scores for individual patients but rather we used the behavioural mapping data as a broad indicator of activity level. The approach was adapted from that successfully employed in two earlier stroke studies concerned with increasing patient activity.28,71 Patients on the stroke unit were screened 24 hours before to determine whether or not behavioural mapping would be feasible. We aimed to recruit a minimum of four and a maximum of 10 patients who met the inclusion criteria and were able to provide consent on the day before the observation. This number was achieved across all sites (see Table 3). The patients were observed at 10-minute intervals between 08.00 and 17.00 or between 13.00 and 20.00 on 3 separate days. This allowed for up to 60 observations of each patient per day. We varied the times and days of the week for behavioural mapping to allow for possible variation in activities by day of the week. During each 10-minute interval, the data for each patient were based on an observation made by the researcher over a period of no longer than 5 seconds. The researcher observed one participant and then progressed to the next participant. The researchers positioned themselves so that they could see the participants – at the same time taking steps to be inconspicuous – and noted where they were, what they were doing and who was present in the same location as the patient. Observations began at the commencement of each 10-minute interval (i.e. 08.00, 08.10, 08.20, 08.30, etc.). The behavioural mapping protocol and recording instrument are in Appendix 7.

In our initial proposal, we anticipated accessing the SSNAP data at an individual patient level to enable us to compare patient dependency during the periods of study, a factor that can influence the activity levels achieved. We had anticipated that we could collect these data on the ward before they were uploaded to SSNAP, but we were not able to gain permission for access.

We agreed that pursuing access to the anonymised SSNAP data would prove overly time-consuming and impossible within the project time scales. This change was discussed in full by the Study Steering Committee and approved by our Health Services and Delivery Research programme manager. An additional justification for this decision was that the national case-mix data are based on the patient cohort within the first 72 hours, that is while at the first routinely admitting stroke unit. Each of the CREATE sites was non-routinely admitting and received patients repatriated from the main routinely admitting hospital linked to their unit.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis

We first describe the processes used to analyse the qualitative data generated from non-participant observations of staff, pre EBCD training and activity, during EBCD (i.e. of the separate patient and carer, staff meetings, joint meetings and co-design meetings) and from interviews with patients, carers and staff pre and post EBCD. The integration of these data in the EBCD evaluation and also in the linked process evaluation involved an iterative approach to analysis that focused initially on the data generated at each site and then progressed, using team half-day analysis meetings, to a comparison between sites, as described below.

Interview data video files (patients and carers at sites 1 and 2) and audio files (staff all sites and patients and carers at sites 3 and 4) were transcribed verbatim. The research fellows and research lead for each site completed an initial thematic analysis of the data at each site (London and Yorkshire) and prepared summary memos identifying the main themes and summarising the key issues related to the presence or absence of activity outside therapy, the opportunities to make changes and the attitudes towards possible changes. These summary memos were then compared and reviewed iteratively in a series of half-day face-to-face meetings (held approximately every 3 months in London or Leeds) by all four researchers, before the summaries were presented to and discussed with Study Steering Committee members.

For observational data, field notes were prepared by each researcher conducting an observation and shared among the researchers for that site. On completion of the series of observations (pre and post implementation and during EBCD activities), summary memos were developed to identify recurring themes and to compare and contrast findings from pre- and post-EBCD activities within and then between sites in London and Yorkshire. Again, these were compared and reviewed iteratively by all four researchers in a series of half-day meetings (as described above) before being shared with Study Steering Committee members. The memos included references to contextual factors considered relevant to service delivery, and to patient experiences of the EBCD process in each site. These processes were used for sites 1 and 2 and then repeated for sites 3 and 4.

Following these half-day meetings and the discussions resulting from presentations of the ongoing data analysis, the core and cross-cutting themes reported in Chapter 5 were developed and agreed by the research leads for London and Yorkshire and shared with Study Steering Committee members.

Integration of data in the experience-based co-design evaluation and process evaluation

The data used in the process evaluation were not generated separately from those used in the main evaluation of the feasibility of using full and accelerated EBCD in the four sites; rather, the same data were critically examined using NPT’s four core constructs and associated components. A data collection plan linked to NPT’s four constructs was developed prior to data collection. The purpose of the plan was to engage with the NPT constructs as data were analysed at each time point, and to identify evidence of (in the summary memos described above) examples such as staff progression from coherence to cognitive participation. This might comprise staff making sense of the EBCD approach, then thinking about what introduction of and support for increased patient activity outside planned therapy would mean for them individually and for the routine service provision currently in place. Once the EBCD activities had ceased at sites 3 and 4, the summary memos and the researcher reflections were reviewed by the research lead for the process evaluation and a draft single integrated account was constructed. This was reviewed by the research team as a whole, and the final agreed account is presented in Chapter 5. Our approach comprised both an ongoing integrative analysis of these data focused on staff and patient engagement with the EBCD process and on designing and implementing changes to promote or directly support increased activity, and a post hoc review of the full integrative data set.

Confirmability of analysis was further enhanced through a process of independent, joint and team half-day analysis and review cycles, after which the emerging analysis was discussed with the Study Steering Committee members. Credibility and transferability of the analytical approach are evident in how we have used detailed data extracts and interview quotations to support plausible explanations of the observational and interview data in terms of participants’ engagement with EBCD and the facilitators of and barriers to its introduction and use in the four sites. We incorporated researcher reflection and reflexivity in the data collection process and used these insights in the team analysis of the data.

Quantitative data analysis

Behavioural mapping

We entered all data into a SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) file and described the frequency of activity occurrence for each participant during each data collection period. This approach, used by Askim et al.,71 included additional categories in social and cognitive activity. These data were used to generate descriptive statistics to quantify the proportion of physical, social and cognitive activity occurring for each patient during the period of observation.

Patient-reported outcome measure and patient-reported experience measure data

These data were entered into a SPSS file and reported as descriptive statistics (or frequency counts) for each item. These data provide insight into patients’ perceived functioning post stroke (PROM) and their experiences on stroke units (PREM). Some of the PREM items sought responses directly related to opportunities and resources for activity.

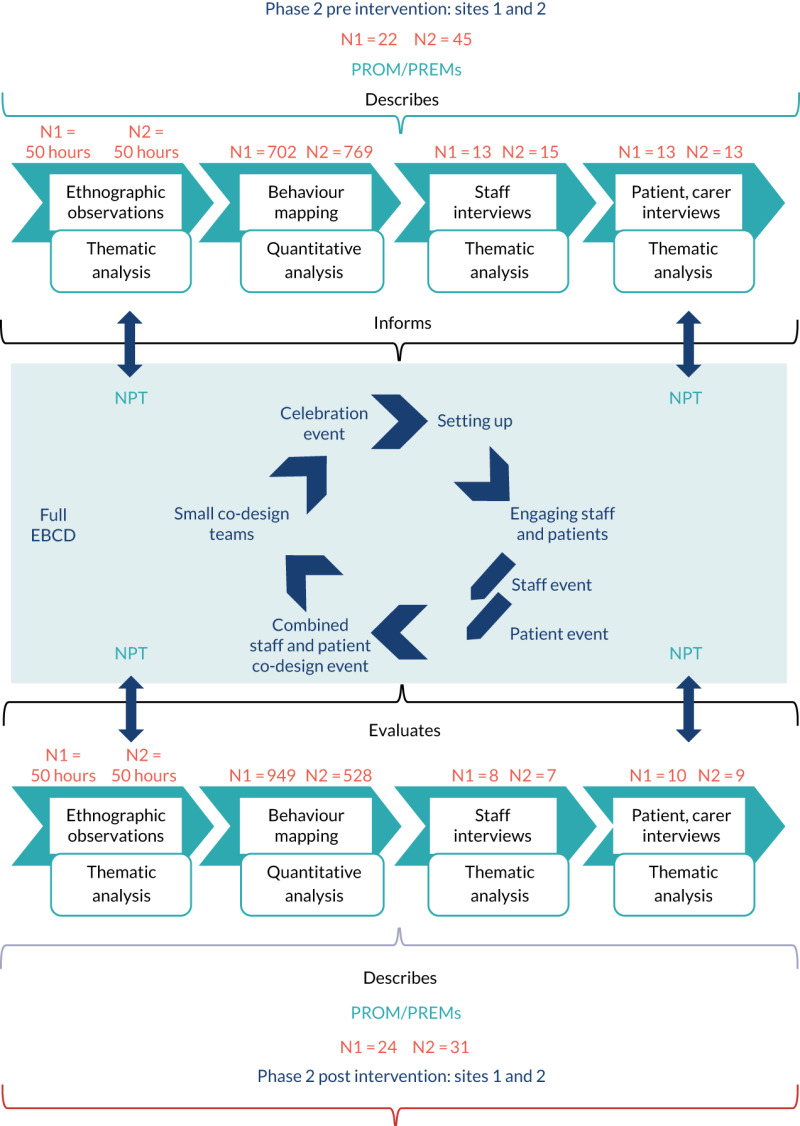

Figure 3 depicts our integrative approach to analysis across the whole data set (qualitative and quantitative) process evaluation.

Process evaluation methods

A parallel process evaluation aimed to understand the functioning of the intervention (i.e. the co-design and generation of new activities in each stroke unit) by examining implementation, mechanisms of impact and contextual factors. Mechanisms of impact refer to the ways in which intervention activities and participants’ engagement with them trigger change in a given setting. Process evaluations contribute to understanding the impact and outcomes of complex interventions. We adopted primarily qualitative methods in the process evaluation (see below), which was informed by NPT.72

Normalisation process theory is an established middle-range theory concerned with understanding how complex interventions are implemented and integrated into existing health-care systems. NPT is conceptualised through four main constructs (Table 4). These constructs or generative mechanisms can help explain how interventions are embedded and ‘normalised’ within routine care. In essence, the mechanisms represent what participants ‘do’ to get the required work done successfully. In general terms, the mechanisms can be understood as participants making sense of a new or different way of working, committing to working in that way, making the effort and working in that way and undertaking continuous evaluation and, if necessary, making adjustments to bring about a situation where what was once a new and complex intervention becomes a normal part of everyday practice. Clearly, not all interventions progress to successful implementation in this way; where this is the case, NPT can aid in understanding the factors that may explain this at both an organisational and an individual level. This focus on the work of implementation and the factors influencing this work was the reason for our use of NPT.

We used NPT to study the EBCD process and the implementation and assimilation of the co-produced interventions in the local context of our study settings. NPT was used in two main ways: first, to guide the generation of data at each site (Table 5) and, second, to inform our analysis of these data and drawing of conclusions related to the similarities and differences in implementing and integrating changes in each of the four study sites. In our analysis we used NPT as a sensitising device in our review of the data generated from observation, interviews and researcher process notes and reflections on EBCD activity. NPT’s constructs were used to identify and think through factors that may act as barriers to or facilitators of using EBCD and introducing change in the four sites. We also used NPT as a structuring device to progress the analysis from identifying barriers and facilitators to linking these, where appropriate, to NPT’s constructs and to develop an explanation of the work of implementation in the participating stroke units.

The CREATE process evaluation differs from some other evaluations of complex interventions in three ways. First, the EBCD approach uses a service improvement methodology in which locally designed changes to services are developed and implemented and therefore variation in the interventions evaluated is likely. Second, we evaluated the implementation and integration of interventions across a full EBCD cycle (approximately 9 months) in two sites and across an accelerated EBCD cycle and a reduced time period (approximately 6 months) in two further sites. Last, the researchers conducting the process evaluation were members of the core research team rather than independent of that team. These researchers were involved in data collection pre and post introduction of the EBCD approach; they also facilitated staff members’, former patients’ and carers’ work in co-design groups during the development and introduction of interventions in the four stroke units.

Data sources for process evaluation

The process evaluation draws on data generated to evaluate the impact of developing and implementing co-produced interventions on the quality and amount of independent and supervised activity occurring outside formal therapy in the four stroke units. Prior to initial data collection in the first two sites, a data collection plan linked to NPT’s four constructs was developed. This identified the kinds of data that would be generated through baseline and post-EBCD data collection at each site, and also participants’ engagement with and experience of each element of the planned EBCD cycle in each site. Process evaluation data collection also focused on additional opportunities presented by observations of training of staff in the EBCD approach, researchers’ reflections on their own involvement in facilitating each element of the EBCD cycles and researchers’ informal and formal engagement with participants in each site as part of recruitment activity and in generating data through observations and interviews.

Ethics and consent

Health Research Authority approval was gained before the project commenced and this included full ethics review by Brighton and Sussex Research Ethics Committee (reference number 16/LO/0212). Local Capacity and Capability assessment was undertaken in each study site and confirmation was gained from each hospital trust. The project was sponsored by St George’s, University of London. The approval letter can be found in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Consent issues were dealt with in several ways as data collection was varied and included data from patients, their family/friends and clinical staff. We gained overall site consent from the senior clinician (principal investigator) at each stroke unit; this enabled us to have a presence on the unit but not to collect data from individual patients or staff. We were aware of the need for sensitivity, especially during non-participant observations and behavioural mapping, and we used a pragmatic process approach to consent, regularly checking that both staff and patients agreed to being observed. Participants in behavioural mapping provided written informed consent. We developed an explanation of the project that was used on arrival and when moving to different parts of the ward; we also displayed a number of posters to describe the project as well as photographs of the research team. We gained individual informed consent for all interviews and behavioural mapping. Consent was implied by return of PROM/PREMs and, where local approvals allowed, some patients were asked for their permission to be contacted before they were discharged. See Report Supplementary Material 2 for examples of consent forms.

Project management and guidance

The project was led and managed jointly by Fiona Jones and David Clarke, with site management by Karolina Gombert-Waldron and Stephanie Honey. A project team of Fiona Jones, David Clarke, Stephanie Honey and Karolina Gombert-Waldron met monthly with co-applicants Glenn Robert, Alastair Macdonald, Ruth Harris and Chris McKevitt for the first 2 years, and every 3–4 months in the final year. Geoffrey Cloud moved to Melbourne, VIC, Australia, prior to the project starting but remained a supporter throughout the project, joining by Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or in person when in the UK. The project team met in person every 9–12 months and members attended a proportion of staff, patient and joint events. Glenn Robert and Alastair Macdonald provided input into the EBCD and co-design activities; Geoffrey Cloud provided clinical advice from a local and national stroke perspective; Glenn Robert and Ruth Harris supported Fiona Jones and David Clarke with the rapid evidence synthesis; Chris McKevitt and the whole group contributed to analysis and interpretation of the empirical findings and report writing.

A Study Steering Committee including independent lay members, academics and senior clinicians met four times during the project and provided the project team with review and guidance.

Approach to public and patient involvement

Stroke survivors were involved in the initial development of our application, and plans were discussed at a Consumer Research Advisory Group that has links with the Cardiac and Stroke Network in Yorkshire, which includes stroke survivors and carers, some with national advisory roles. The outline was also presented in round-table discussions with stroke survivors and carers at the Yorkshire Stroke Research network consumer conference. Consumer Research Advisory Group members and conference participants strongly supported the proposed research. Most expressed a view that active inpatient rehabilitation was central to recovery after stroke but felt that they did not receive the amount of therapy identified in the national standard. Carers indicated that they wanted to help with rehabilitation but did not know how, and did not receive training from staff in this area. Two stroke survivors and one family member participated in research proposal writing groups, attending meetings in Leeds and London. Their comments helped the research team appreciate how the collaborative research process proposed may be viewed and engaged with by stroke survivors.

Patients’ and carers’ voices, experiences and ideas are a central tenet of EBCD. As such, active patient and carer involvement was a feature of every stage. Patients and carers took part in separate events and joint events with staff; they formed at least 50% of the membership of co-design groups and attended final events held at each site to share CREATE findings and discuss methods of dissemination. Overall, CREATE enabled patients and their carers to work in close partnership with front-line health-care professionals to develop, pilot and evaluate innovations in the delivery of rehabilitation therapy in acute settings.

In addition to patient and public involvement in intervention development, a stroke survivor and a carer were involved through their role on the CREATE Study Steering Committee. They participated in all aspects of the study, including a review of participant information sheets, discussion with researchers about conducting observations and interviews with patients and staff, and helped researchers shape the messaging in the EBCD feedback events.

Patients and carers have been updated about the findings at various stages of the project in various ways, including newsletters, individualised letters and e-mails, as well as from attending feedback events. For an example, see Report Supplementary Material 4.

Figures

FIGURE 3

Data analysis for both the evaluation and the intervention (EBCD).

Tables

TABLE 3

Timings of data collection and the methods used

| Site | Staff interviews: EBCD and evaluation | Patient interviews: EBCD and evaluation | Carer interviews: evaluation | PROMs/PREMs: evaluation | BM: number of participants | BM: number of observations | Observations: EBCD and evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 pre | 13 | 9 | 4 | 22 | 9 | 702 | 50.2 hours |

| Site 1 post | 8 | 5 | 5 | 24 | 7 | 949 | 46.5 hours |

| Site 2 pre | 15 | 9 | 4 | 45 | 11 | 769 | 48 hours |

| Site 2 post | 7 | 6 | 2 | 26 | 10 | 528 | 44 hours |

| Site 3 pre | 6 | 9 | 3 | 28 | 12 | 945 | 49.2 hours |

| Site 3 post | 8 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 7 | 782 | 37 hours |

| Site 4 pre | 7 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 655 | 44 hours |

| Site 4 post | 12 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 701 | 46 hours |

| Total | 76 | 53 | 27 | 179 | 68 | 6031 | 364.9 hours |

BM, behavioural mapping.

TABLE 4

Constructs of NPT

| NPT construct | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Coherence | The sense-making work that people do individually and collectively when faced with implementing changes to existing working practices. This would include differentiating new practices from existing work and thinking through not only the perceived value and benefits of desired/planned changes but also what work will be required of individual people in a setting to bring about these changes |

| Cognitive participation | The work that people need to do to engage with and commit to a new set of working practices. This often requires bringing together those who believe in and are committed to making changes happen. This also involves people working together to define ways to implement and sustain the new working practices |

| Collective action | The work that will be required of people to actually implement changes in practices, including preparation and/or training of staff. Often this entails rethinking how far existing work practices and the division of labour in a setting will have to be changed or adapted to implement the new practices. This requires consideration of not only who will do the work required, but also the skills and knowledge of people who will do the work and the availability of the resources they need to enact and sustain the new working practices |

| Reflexive monitoring | People’s individual and collective ongoing informal and formal appraisal of the usefulness or effectiveness of changes in working practices. This involves considering how the new practices affect the other work required of individuals and groups and whether or not the intended benefits of the new working practices are evident for the intended recipients and staff |

TABLE 5

Data sources used for process evaluation

| Data source | Timing | Linked NPT construct |

|---|---|---|

| EBCD training events for local champions: researcher observations; participant evaluations | Prior to EBCD cycles commencing | Coherence |

| Non-participant observations of routine working practices, interactions between staff, patients and carers and between staff | Pre EBCD cycles commencing and post co-design group activity and implementation of ‘interventions’ and changes to working practices | Coherence, cognitive participation, collective action |

| Semistructured (audio-recorded) interviews with stroke service staff | Pre EBCD cycles commencing and post co-design group activity and implementation of ‘interventions’ and changes to working practices. Post co-design group activity and implementation interviews included volunteers, and staff working outside the stroke service who participated in EBCD elements | Coherence, cognitive participation, reflexive monitoring |

| Semistructured (video-recorded) interviews with former inpatient stroke survivors and carers | Pre EBCD cycles commencing | Coherence |

EBCD cycle elements:

|

Across ≈9 months at sites 1 and 2 Across ≈6 months at sites 3 and 4 | Coherence, cognitive participation and collective action |

| Semistructured (audio-recorded) interviews with former inpatient stroke survivors and carers | Post co-design group activity and implementation of ‘interventions’ and changes to working practices in the stroke units. These interviews included EBCD participants and stroke survivors who had been inpatients during the EBCD activity and implementation phase | Coherence and reflexive monitoring |

| Study oversight groups’ meeting records and e-mail responses to researcher updates | Ongoing where these meetings could be established | Coherence and cognitive participation |

| Researcher reflections on facilitating unplanned elements in EBCD cycles, in recruitment activity and in generating data through observations and interviews | Ongoing | Informing evaluation and analysis of participants’ engagement with the EBCD process |

Copyright © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.