Pharmacological Interventions for Chronic Pain in Pediatric Patients: A Review of Guidelines

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Authors

Srabani Banerjee and Robyn Butcher.Abbreviations

- CNCP

chronic non-cancer pain

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Context and Policy Issues

Chronic pain is defined as recurrent or persistent pain that extends longer than the expected healing time (generally three months or more).1,2 Chronic pain affects the individual, as well as the individual’s family, society and the health care system.3 Untreated chronic pain in childhood is associated with risk of subsequent pain as well as physical and psychological impairment in adulthood.2 A higher proportion of chronic pain in adulthood was reported in those who had chronic pain in adolescence compared with those who were pain free in adolescence.2 Pathophysiological classifications of chronic pain in the pediatric population include nociceptive pain (somatic or visceral), neuropathic pain (from damage to or dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous system) and idiopathic pain (no known cause).4,5 The most common chronic pain disorders in the pediatric population include primary headache, centrally mediated abdominal pain syndromes, and chronic/recurrent musculoskeletal and joint pain.2

Globally, pain is a common feature among children and adolescents, and in many it is chronic.6,7 A systematic review8 of studies on the prevalence rates of chronic pain in children and adolescents reported that there was wide variation in the prevalence rates depending on demographics and psychosocial factors; prevalence rates were 8% to 83% for headache, 4% to 53% for abdominal pain, 4% to 40% for musculoskeletal pain, 14% to 24% for back pain, and 5% to 88% for other pain. According to the 2007/2008 Canadian Community Health Survey of individuals in the age group 12 years to 44 years the prevalence of chronic pain was estimated as 9.1% in males and 11.9% in females; for the pediatric subgroup (12 years to 17 years) the prevalence was 2.4% in males and 5.9% in females.3

The development and persistence of chronic pain involve multiple, integral, neural pain networks (i.e., peripheral, spinal, and brain) that interact in a complex way to contribute to an individual’s experience of pain.8 In children these peripheral, spinal, and brain networks are not mature and change over time as the child matures, which adds further complexity to understanding, evaluating and treating pain in the pediatric population.8

Pharmacological agents have been used for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. These include acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anti-depressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids. NSAIDS include agents such as aceclofenac, acetylsalicylic acid, celecoxib, choline magnesium trisalicylates, diclofenac, etodolac, etoricoxib, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, mefenamic acid, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, parecoxib, phenylbutazone, piroxicam, sulindac, tenoxicam, and tiaprofenic acid.4 Anti-depressants include agents such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, duloxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion.9 Anticonvulsants include agents such as gabapentin and pregabalin.10 Opioids include agents such as buprenorphine, codeine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol.7

There appears to be limited evidence available with respect to pharmacological treatments for management of chronic pain in pediatric patients. One systematic review6 reported that there was no evidence from RCTs to support or refute the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for treating chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) in children and adolescents. A second systematic review4 investigated the clinical efficacy of NSAIDs for treating CNCP in children and adolescents. The authors reported that there were few RCTs identified and they were of low or very low quality, and they had insufficient data for analysis; hence they were unable to comment on the efficacy or harm of NSAIDs for treating CNCP in children and adolescents. A third systematic review9 investigated the clinical efficacy of antidepressants for treating CNCP in children and adolescents. The authors reported that there were few RCTs identified and they were of small sample size and of very low quality, and they had insufficient data for analysis; hence they were unable to comment on the efficacy or harm of anti-depressants for treating CNCP in children. A fourth systematic review7 reported that there was no evidence from RCTs to support or refute the use of opioids for treating CNCP in children and adolescents. There appears to be uncertainty regarding clinical effectiveness pharmacological interventions for treating CNCP in children and adolescents. Hence guidelines regarding the use of pharmacological interventions for treatment of chronic pain is pediatric and young people are important.

The aim of this report is to review the evidence-based guidelines regarding pharmacological interventions for pediatric and youth patients with chronic pain.

Research Question

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding on- and off-label pharmacological interventions for pediatric and youth patients with chronic pain?

Key Findings

One relevant evidence-based guideline on the management of chronic pain in children and young people was identified. The level of evidence going from the highest to the lowest was scored as 1++, 1+, 1-, 2++, 2+, 2-, 3, or 4 for the evidence presented in the guideline. Recommendations on various pharmacological treatments were presented but the strengths of recommendations were not provided and were based mainly on expert opinion (evidence level: 4).

Lidocaine (5%) patches should be considered in the management of children and young people with localized neuropathic pain, particularly when improving compliance with physiotherapy interventions (evidence level: 3).

Low dose amitriptyline should be considered for treating children and young people with functional gastrointestinal disorders (evidence level: 1-), chronic daily headache, chronic widespread pain or mixed nociceptive/neuropathic back pain (evidence level: 3).

Recommendations for use of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentin, pregabalin, bisphosphonate, baclofen, pizotifen, and famotidine for management of chronic pain varied depending on the types of chronic pain and were based on expert opinion.

Based on expert opinion, opioids are rarely recommended for chronic pain because of their adverse effect profile, and if used should be used as short a duration as possible.

The recommendations need to be considered in the light of the limitations (such as evidence available was of limited amount and limited quality, and recommendations were based on expert opinion; and it was unclear if generalizable to the Canadian context).

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including Ovid Medline, the Cochrane Library, the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, the websites of Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused internet search. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concepts were pediatrics and chronic pain. Search filters were applied to limit retrieval to guidelines. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2015 and April 3, 2020.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Selection Criteria.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in Table 1, they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2015. Guidelines with unclear methodology or irrelevant populations were also excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included evidence-based guidelines were critically assessed by one reviewer, using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool.11 Summary scores were not calculated for the included guidelines; rather, the strengths and limitations of the included guideline were described.

Summary of Evidence

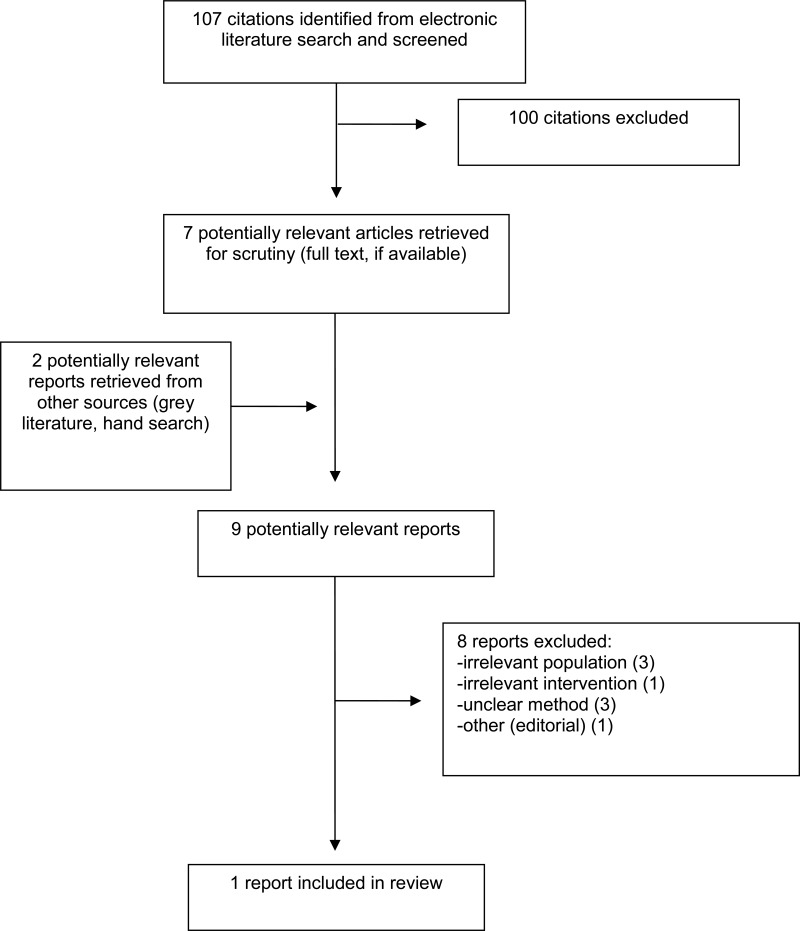

Quantity of Research Available

A total of 107 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 100 citations were excluded and seven potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Two potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these nine potentially relevant articles, eight publications were excluded for various reasons, and one publication met the inclusion criteria and was included in this report. This comprised one evidencebased guideline.10 Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA12 flowchart of the study selection.

Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the guideline10 are summarized and additional details are provided in Appendix 2, Table 2.

Study Design

One relevant evidence-based guideline10 was identified. The guideline development group was multidisciplinary and comprised of individuals representing relevant stakeholder groups, such as a consultant in pediatric anesthesia and pain management, pediatrician, pediatric surgeon, clinical psychologist, physiotherapist, pharmacist, nurse, and patient representative. A systematic literature search was conducted to identify evidence; study designs included in the literature search were not reported. The methodology of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) was used for assessing the quality of evidence. The SIGN methodology has a recommendation grading system. However, it appears that recommendations that were relevant for this report could not be graded by the guideline development group. Recommendations were based on consensus; method for achieving consensus was not presented.

Country of Origin

The guideline10 was from the UK and was produced by the Scottish government.

Patient Population

The guideline10 was for use by health care professionals for the management of chronic pain in children and young people.

Interventions and Comparators

The guideline10 presented several pain management strategies: pharmacological interventions, physical therapies, psychological therapies, dietary therapies, complementary and alternative therapies, and surgical interventions. Of these, pharmacological interventions (acetaminophen, NSAIDs, anti-depressants, anticonvulsants and opioids) were of relevance for this report and are discussed here.

Outcomes

The guideline10 presented recommendations for management of chronic pain in children and young people. The impact of the pharmacological interventions on pain status and their safety were considered.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

The critical appraisal of the included guideline10 is summarized and additional details are provided in Appendix 3, Table 3.

The scope and purpose were stated. The guideline development group comprised of individuals with relevant expertise, as well as a patient representative. The recommendations were clearly stated. A systematic literature search was undertaken to identify evidence, and the method for formulating the recommendations was according to the SIGN methodology. The guideline was externally reviewed. It appears that inclusion and exclusion criteria for evidence selection were not clearly described, hence it was unclear how the evidence was selected; also, the link between recommendation and supporting evidence was not always clear. For the recommendation on amitriptyline for functional gastrointestinal disorder, it was unclear why the level of evidence that was presented alongside the recommendation did not appear to match the evidence level presented for the related study on which it was based. Applicability of the guidelines was not described. Competing interests of the guideline development group members were not presented, hence it was unclear if there were any potential issues.

Summary of Findings

One relevant evidence-based guideline10 (on the management of chronic pain in children and young people) was identified and recommendations regarding pharmacological interventions are summarized below and details are presented in Appendix 4, Table 4.

High quality evidence with respect to pharmacological treatment of chronic pain in the pediatric patients was sparse and recommendations were based on consensus opinion of the experts. Recommendations were not graded. Most of the recommendations were based on expert opinion (i.e., evidence level: 4), unless the evidence level was indicated in the guideline publication along with the recommendation. Recommendations presented below relate to the management of chronic pain in children and young people.

Based on consensus opinion, this guideline recommends that pharmacological interventions should only be started after careful assessment, should be in the context of a multidisciplinary approach, and there should be ongoing planned reassessment of efficacy and side effects.

Additional recommendations for several classes of drugs were also provided:

Non-opioids

Simple analgesics and topical analgesics:

Acetaminophen and NSAIDs should be considered in the treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain in children and young people; however, they should be limited to the shortest possible duration. Topical NSAIDs should be considered for localized, chronic regional pain syndrome and non-neuropathic pain in children and young people. Lidocaine (5%) patches should be considered in the management of children and young people with localized neuropathic pain, particularly when improving compliance with physiotherapy interventions (evidence level: 3).

Anticonvulsants and antidepressants:

Antiepileptic drugs may be considered as part of a multimodal strategy for managing neuropathic pain in children and young people. Low dose amitriptyline should be considered for the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and young people (evidence level: -1), chronic daily headache, chronic widespread pain or mixed nociceptive/neuropathic back pain (evidence level: 3). Gabapentin should be considered as first line anticonvulsant, and pregabalin could be considered as second line, when gabapentin is either not tolerated or is ineffective.

Non-standard analgesics

Bisphosphonates should be considered for managing bone pain in children and young people with osteogenesis imperfecta. Intrathecal baclofen should be considered for managing pain associated with spasticity in children and young people with cerebral palsy. Pizotifen should be considered for abdominal migraine and famotidine for dyspepsia in children and young people.

Opioids

Opioids are rarely indicated for chronic pain due to their adverse effects. Opioids should be restricted to as short a time as possible with regular monitoring of efficacy and adverse effects. Treatment with codeine is not recommended in children under 12 years of age, and should be avoided in adolescents, particularly in those with respiratory problems or those who rapidly metabolize CYP2D6.

Limitations

As the evidence identified by the guideline authors was of limited amount and limited quality, the recommendations were mostly based on consensus opinion of the experts.

The pediatric population generally comprises infants (less than 1 year), children (1 to 9 years) and adolescents (10 to 18 years).6,7 The selected guideline10 presented recommendations for pharmacological treatments for management of chronic pain in children and young people; it was difficult to determine if the age group considered was specifically 6 years to 18 years or if the recommendations would apply to a particular age group and not to another age group within that range of 6 years to 18 years.

The guideline was prepared by the Scottish government, hence its generalizability to the Canadian context is unclear.

The recommendations need to be considered in the light of the limitations.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

One relevant evidence-based guideline10 on the management of chronic pain in children and young people was identified. There was limited evidence available with respect to pharmacological treatment of chronic pain in the pediatric patients and the evidence was not of high quality. The level of evidence going from the highest to the lowest was scored as 1++, 1+, 1-, 2++, 2+, 2-, 3, or 4 for the evidence presented in the guideline. Most of the recommendations were based on expert opinion (i.e., evidence level: 4), unless the evidence level was indicated along with the recommendation. The strengths of recommendations were not provided.

Lidocaine (5%) patches should be considered in the management of children and young people with localized neuropathic pain, particularly when improving compliance with physiotherapy interventions (evidence level: 3). Low dose amitriptyline should be considered for treating children and young people with functional gastrointestinal disorders (evidence level: 1-), chronic daily headache, chronic widespread pain or mixed nociceptive/neuropathic back pain (evidence level: 3). Recommendations for the use of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentin, pregabalin, bisphosphonate, baclofen, pizotifen, and famotidine for management of chronic pain were based on expert opinion. Based on expert opinion, opioids are rarely indicated for chronic pain because of their adverse effect profile, and if used, should be used for as short a duration as possible.

To support guideline development, good quality evidence on the effectiveness of various pharmacological agents for treatment of chronic pain in children and young people is needed. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the clinical effectiveness of the various pharmacological agents in treating chronic pain in various age groups in the pediatric population. Also, long-term studies targeting younger children with pain, may be useful to determine the protective effect of early intervention if any, in preventing or reducing transition to chronic pain later in life.

References

- 1.

- Liossi C, Howard RF. Pediatric chronic pain: biopsychosocial assessment and formulation. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5). [PubMed: 27940762]

- 2.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Goubert L. Pediatric pain treatment and prevention for hospitalized children. Pain Rep. 2020;5(1):e804. [PMC free article: PMC7004501] [PubMed: 32072099]

- 3.

- Ramage-Morin PL, Gilmour H. Chronic pain at ages 12 to 44. Health Rep. 2010;21(4):53–61. [PubMed: 21269012]

- 4.

- Eccleston C, Cooper TE, Fisher E, Anderson B, Wilkinson NM. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD012537. [PMC free article: PMC6460508] [PubMed: 28770976]

- 5.

- Watson JC. Overview of pain. Merck Manual. Professional edition 2020; https://www

.merckmanuals .com/professional /neurologic-disorders /pain/overview-of-pain. Accessed 2020 May 04. - 6.

- Cooper TE, Fisher E, Anderson B, Wilkinson NM, Williams DG, Eccleston C. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD012539. [PMC free article: PMC6484395] [PubMed: 28770975]

- 7.

- Cooper TE, Fisher E, Gray AL, et al. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD012538. [PMC free article: PMC6477875] [PubMed: 28745394]

- 8.

- King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152(12):2729–2738. [PubMed: 22078064]

- 9.

- Cooper TE, Heathcote LC, Clinch J, et al. Antidepressants for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD012535. [PMC free article: PMC6424378] [PubMed: 28779487]

- 10.

- Management of chronic pain in children and young people. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh (GB): Scottish Government; 2018: https://www

.gov.scot /publications/management-chronic-pain-children-young-people/. Accessed 2020 May 04. - 11.

- Agree Next Steps C. The AGREE II Instrument. Hamilton (ON): AGREE Enterprise; 2017: https://www

.agreetrust .org/wp-content/uploads /2017/12/AGREE-II-Users-Manual-and-23-item-Instrument-2009-Update-2017.pdf. Accessed 2020 May 04. - 12.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [PubMed: 19631507]

- 13.

- Management of chronic pain: a national clinical guideline. (SIGN publication no. 136). Edinburgh (GB): Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN); 2019: https://www

.sign.ac.uk /assets/sign136_2019.pdf. Accessed 2020 May 04. - 14.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN methodology. 2019; https://www

.sign.ac.uk/methodology. Accessed 2020 May 04.

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publication

Table 2

Characteristics of Included Guideline.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3

Strengths and Limitations of Guidelines using AGREE II.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 4. Summary of Recommendations in Included Guideline (PDF, 253K)

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Guidelines with unclear methodology

- Chronic pain. Care for adults, adolescents and children. (draft). Quality standards. Toronto (ON): Health Quality Ontario; 2019: https://www

.hqontario .ca/portals/0/documents /evidence/quality-standards /qs-chronic-pain-clinical-guide-1810-en.pdf. Accessed 2020 May 04. - Politei JM, Bouhassira D, Germain DP, et al. Pain in Fabry disease: practical recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22(7):568–576. PubMed:PM 27297686 [PMC free article: PMC5071655] [PubMed: 27297686]

- Politei JM, Gordillo-Gonzalez G, Guelbert NB, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of pain in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis in Latin America. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(1):146–152. PubMed: PM 29649527 [PubMed: 29649527]

About the Series

Version: 1.0

Suggested citation:

Pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in pediatric patients: a review of guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2020 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.

The copyright and other intellectual property rights in this document are owned by CADTH and its licensors. These rights are protected by the Canadian Copyright Act and other national and international laws and agreements. Users are permitted to make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes only, provided it is not modified when reproduced and appropriate credit is given to CADTH and its licensors.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/