NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

33. Integrated patient information systems

33.1. Introduction

It is generally accepted that appropriate information sharing within departments in an organisation and between different organisations is of importance in supporting co-ordinated care for patients, improving patient experience and achieving greater efficiency and value from health delivery systems.

An integrated patient information system would allow authorised health and social care professionals to have access to the patient’s clinical information (for example, laboratory results, medications, allergies and clinical notes) from multiple providers. It could also allow the patient to view the record and where appropriate add any self-monitoring information. Many benefits and efficiencies can flow from information being recorded, at contact with health and care services, and shared securely between those providing care.

33.2. Review question: Do integrated patient information systems throughout the AME pathway (primary and secondary care) improve patient outcomes?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

33.3. Clinical evidence

One study was included in the review;7 these are summarised in Table 2 below. The study reported only important outcomes and did not report any critical outcomes stated in the protocol.

Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 3). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, forest plots in Appendix C, study evidence tables in Appendix D, GRADE tables in Appendix E and excluded studies list in Appendix F.

33.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

In the absence of health economic evidence, unit costs were presented to the guideline committee – see Chapter 41 Appendix I.

33.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

One study comprising 1616 participants evaluated integrated patient information system for improving outcomes in secondary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence for integrated patient information systems suggested there was no difference for repeat visits to the ED within 28 days (moderate quality) or duplication of diagnostic tests between ED and the family physician (very low). However, the evidence for integrated patient information systems suggested there was a possible increase of repeat visits to the ED within 14 days (low quality) and duplication of diagnostic tests in speciality consultations (low quality) compared to no integrated patient information systems.

Economic

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

33.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendation | - |

| Research recommendations | RR14. What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of different methods for integrating patient information throughout the emergency medical care pathway? |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Mortality, avoidable adverse events (including missed or delayed treatments and missed or delayed investigations, prescribing errors − errors of omission or commission and medicines reconciliation), quality of life and patient and/or carer satisfaction were considered by the committee to be critical outcomes. Length of stay, ED admissions, unnecessary duplication of tests and staff satisfaction were considered to be important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

There was evidence from 1 cross-over cluster randomised trial comparing integrated patient information systems with no integrated patient information systems. The evidence for integrated patient information systems suggested there was no difference for repeat visits to the ED within 28 days or duplication of diagnostic tests between ED and the family physician. However, the evidence for integrated patient information systems suggested there was a possible increase of repeat visits to the ED within 14 days and duplication of diagnostic tests in speciality consultations compared to no integrated patient information systems. No evidence was available for the outcomes mortality, avoidable adverse events (including missed or delayed treatments and missed or delayed investigations), prescribing errors (errors of omission or commission, medicines reconciliation), quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, length of stay and staff satisfaction. The committee also noted that there was a lack of evidence identified on patient safety outcomes in this review. The committee were of the view that, given properly designed IT systems, information sharing between primary/secondary care and social care would be effective and should be beneficial for patients, particularly regarding prescription of medications and documenting allergies. However, the trials available did not demonstrate these effects. Personal experience of shared information systems by the committee indicated that they could be helpful in caring for patients, particularly those with multimorbidity. However, in view of the lack of evidence the committee considered that a research recommendation would be most appropriate in this area. It would be particularly helpful to understand what the optimum way to configure the system would be to deliver best use of limited resources. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

The committee discussed qualitatively the potential costs involved for an integrated information system. The committee considered there would be a significant upfront cost of these systems during development and during implementation as they would probably be used alongside the existing system. Additional long-term maintenance costs might be equivalent to existing systems, but data security and linkage across different platforms would probably increase costs. There would also be additional resource implications for performance upgrades, and ensuring that they remain fit for purpose. Given that the integration of systems could potentially provide benefits to a large number of patients over time, the upfront costs involved in the implementation would become relatively small when measured per person. The committee also considered the benefits to patients of the different providers having access to information about drug prescriptions and allergies; improvements in patient safety could well justify the implementation costs. The unit costs of tests and ED presentations were presented to the committee for them to consider the potential cost savings (Chapter 41 Appendix I). |

| Quality of evidence | The quality of the evidence for the study comparing integrated patient information systems with no integrated patient information systems was graded from moderate to very low; this was mainly due to risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision. |

| Other considerations |

The integration of information systems is essential to support shared care and to provide consistent patient centred care to individuals who may be mobile and have their care delivered in multiple facilities. Clinical care increasingly requires healthcare professionals to access patient record information that may be distributed across multiple sites, held in a variety formats. In hospitals, information technologies tend to combine different modules or subsystems, resulting in a best-of-breed approach. To integrate clinical information systems in a way that will improve communication and data use for healthcare delivery, research and management, many different issues must be addressed. To consistently combine data from heterogeneous sources takes a great deal of time and effort because the individual feeder systems usually differ in several aspects, such as functionality, presentation and data representation. It will be challenging to make electronic health records operable between sites with the preservation of clinical meaning. The committee noted that the effective sharing of information has been recognised to be fundamental in the care of patients and is in line with the additional Caldicott Principle5 published in April 2013 which states “the duty to share information can be as important as the duty to protect patient confidentiality”. Healthcare professional should have training into using the systems developed which also includes regular updates. The training should also outline the Caldicott Principles and demonstrate best practice in this aspect but also best practice in the efficient use of such systems. Patient consent for information sharing between sectors of health and social care would be required. Sometimes consent is implied, for example, when a patient is admitted to hospital, all relevant healthcare professionals who are caring for the patient should have access to that information; however, those who are not should not. When considering sharing large and important amounts of information about a patient, more formal consent will be required. Timely access to shared patient information would be particularly important when caring patients with cognitive impairment or in meeting a patient’s preferences in terms of end of life care. Systems are likely to change in the future as technology advances, offering greater functionalities and rapid access to the results of investigations, combined with clinical decision support. Current examples of integrated patient information systems are NHS Spine and Enhanced Summary Care Records. The committee was aware that, in several locations around the country, web- based integrated patient information systems between primary and secondary care are currently being set up. This research recommendation is intended to encourage parallel evaluation of local innovation. |

References

- 1.

- Akbarov A, Williams R, Brown B, Mamas M, Peek N, Buchan I et al. A two-stage dynamic model to enable updating of clinical risk prediction from longitudinal health record data: illustrated with kidney function. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2015; 216:696–700 [PubMed: 26262141]

- 2.

- Aubin M, Vezina L, Verreault R, Fillion L, Hudon E, Lehmann F et al. Patient, primary care physician and specialist expectations of primary care physician involvement in cancer care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012; 27(1):8–15 [PMC free article: PMC3250542] [PubMed: 21751057]

- 3.

- Cifuentes M, Davis M, Fernald D, Gunn R, Dickinson P, Cohen DJ. Electronic health record challenges, workarounds, and solutions observed in practices integrating behavioral health and primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2015; 28: Suppl 1:S63–S72 [PMC free article: PMC7304941] [PubMed: 26359473]

- 4.

- Cox CE, Curtis JR. Using technology to create a more humanistic approach to integrating palliative care into the intensive care unit. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2016; 193(3):242–250 [PubMed: 26599829]

- 5.

- Department of Health. Information: to share or not to share? The Information Governance Review, 2013. Available from: https://www

.gov.uk/government /uploads/system /uploads/attachment_data /file/192572 /2900774_InfoGovernance_accv2.pdf - 6.

- Flemming D, Hubner U. How to improve change of shift handovers and collaborative grounding and what role does the electronic patient record system play? Results of a systematic literature review. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2013; 82(7):580–592 [PubMed: 23628146]

- 7.

- Lang E, Afilalo M, Vandal AC, Boivin JF, Xue X, Colacone A et al. Impact of an electronic link between the emergency department and family physicians: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006; 174(3):313–318 [PMC free article: PMC1373712] [PubMed: 16399880]

- 8.

- Moore P, Armitage G, Wright J, Dobrzanski S, Ansari N, Hammond I et al. Medicines reconciliation using a shared electronic health care record. Journal of Patient Safety. 2011; 7(3):148–154 [PubMed: 21857238]

- 9.

- Overhage JM, Dexter PR, Perkins SM, Cordell WH, McGoff J, McGrath R et al. A randomized, controlled trial of clinical information shared from another institution. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002; 39(1):14–23 [PubMed: 11782726]

- 10.

- Sicotte C, Lapointe J, Clavel S, Fortin M-A. Benefits of improving processes in cancer care with a care pathway-based electronic medical record. Practical Radiation Oncology. 2016; 6(1):26–33 [PubMed: 26598908]

- 11.

- Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2005; 200(4):538–545 [PubMed: 15804467]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 4Review protocol: Integrated Patient Information Systems

| Review question | Do integrated patient information systems throughout the AME pathway (primary and secondary care) improve patient outcomes? |

|---|---|

| Guideline condition and its definition | AME. |

| Objectives |

Patient records are not easily accessible by all health care professionals (HCP) involved in the care of a patient, particularly if they are working in separate organisations. Information about patients’ management, care provided and requirements is often lost during transfers of care. This can impair communication between HCPs and can lead to errors and unnecessary duplication all of which can lead to avoidable adverse events, delays and increase in HCP demand. A working definition of ‘integration’ is the management and delivery of health services so that clients receive a continuum of preventative and curative services, according to their need over time and across different health systems. IT or informatics integration involves sharing communication, data collection, storage, analysis and dissemination strategies. An integrated IT system throughout the AME pathway should improve patient care and thus outcomes. |

| Review population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed AME. |

| Adults and young people (16 years and over). | |

| Line of therapy not an inclusion criterion. | |

|

Interventions and comparators: generic/class; specific/drug (All interventions will be compared with each other, unless otherwise stated) |

Integrated patient information systems throughout AME pathway (including primary care, secondary care and social care); patient information database (for example, summary care records) accessible to all HCPs directly involved in the care of their patients. Integrated patient information systems throughout AME pathway (including primary care, secondary care and social care); shared IT systems between primary and secondary care. Integrated patient information systems throughout AME pathway (including primary care, secondary care and social care); community/pre-hospital/ambulance care. No integrated patient information systems throughout AME pathway (including primary care, secondary care and social care); lack of accessibility to patent information databases to all HCPs involved in care of patients. |

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design |

Systematic Review RCT Quasi-RCT Non-randomised comparative study Prospective cohort study Retrospective cohort study Case control study Controlled before and after study Before and after study Non randomised study |

| Unit of randomisation | Patient. |

| Crossover study | Permitted. |

| Minimum duration of study | Not defined. |

| Other inclusions | Adults and young people (16 years and over). |

| Other exclusions |

Studies from non-OECD countries. Non-English language studies. |

| Subgroup analyses if there is heterogeneity |

|

| Search criteria |

Databases: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library. Date limits for search: None. Language: English. |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

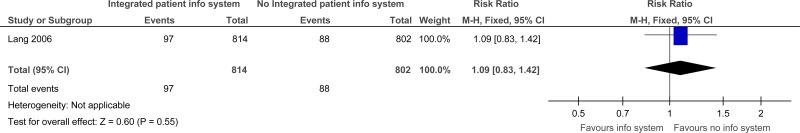

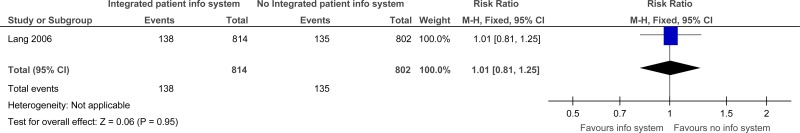

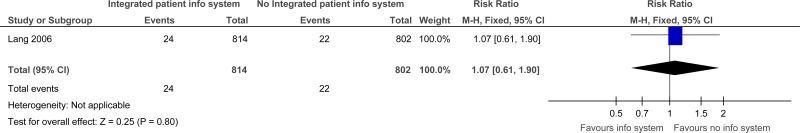

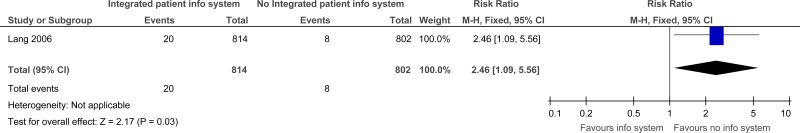

C.1. Integrated patient information systems versus No Integrated patient information systems

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (301K)

Appendix E. GRADE tables

Table 5Clinical evidence profile: Integrated Patient Information Systems versus no Integrated Patient Information Systems

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Integrated patient info system | No Integrated patient info system | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Repeat visits to the ED within 14 days | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

97/814 (11.9%) | 11% | RR 1.09 (0.83 to 1.42) | 10 more per 1000 (from 19 fewer to 46 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Repeat visit to the ED within 28 days | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

138/814 (17%) | 16.8% | RR 1.01 (0.81 to 1.25) | 2 more per 1000 (from 32 fewer to 42 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| Duplication of diagnostic tests (between ED and the family physician office) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

24/814 (2.9%) | 2.7% | RR 1.07 (0.61 to 1.9) | 2 more per 1000 (from 11 fewer to 24 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Duplication of diagnostic tests (in speciality consultations) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

20/814 (2.5%) | 1% | RR 2.46 (1.09 to 5.56) | 15 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 46 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID point, and downgraded by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed 2 MID points.

Appendix F. Excluded clinical studies

Table 6Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Akbarov 20151 | Incorrect interventions. A 2-stage dynamic fixed-effect modelling to demonstrate the use of electronic records and repeated measures of risk factors, to enable deeper understanding of the relationship between the full longitudinal trajectory of risk factors and outcomes. |

| Aubin 20122 | Incorrect interventions. Prospective longitudinal survey of primary care physicians, lung cancer patients and cancer specialists. The objective was to compare lung cancer patient, PCP and specialist expectations regarding PCP involvement in co-ordination of care, emotional support, information transmission and symptom relief at the different phases of cancer. |

| Cifuentes 20153 |

Inappropriate intervention -the article describes the electronic health record related experiences of practices. No extractable outcomes Inappropriate study design- observation study |

| Cox 20164 | Inappropriate study design. Review article |

| Flemming 20136 | Systematic review- references checked |

| Moore 20118 | Incorrect comparison. EHR (electronic health records) used as a secondary information source versus EHR used as an initial information source. |

| Overhage 20029 | Study data not reported for the intervention and control groups separately. |

| Sicotte 201610 | Not AME- study evaluated the impact of application of electronic medical record (EMR) in an ambulatory care centre in medical and radiation oncology. |

| Van eaton 200511 | Incorrect interventions. Computerised rounding and sign-out system. Study has been included in the ‘ward rounds’ review. |

Tables

Table 1PICO characteristics of review question

| Population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME. |

|---|---|

| Intervention(s) |

|

| Comparison(s) | No integrated patient information systems throughout AME pathway (including primary care, secondary care and social care).

|

| Outcomes | Patient outcomes;

|

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

Table 2Summary of studies included in the review

| Study | Intervention and comparison | Population | Outcomes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lang 20067 Cross-over cluster randomised trial Canada |

Intervention: When family physicians were in the intervention phase, they received detailed clinical information of their patients visit to the emergency department through a secure Web based standardised communication system (SCS). The SCS programme automatically issued advisory emails (at 0700) once per day to all family physicians whose patients or patients had presented to the emergency department within the previous 24 hours. Control: When family physicians were in the control phase, they received a carbon copy of the first page of the emergency physicians’ notes by regular mail within 1-2 weeks of the visit to the emergency department; the standard practice at the emergency department. |

n=2022 Patients whose family physician was participating in the study were approached for recruitment upon presentation to the emergency department. For their visit to be eligible, patients had to be 18 years of age or older, have been seen by the participating family physician at least once within the previous 2 years. Participants agreed to have their clinical information extracted from their emergency department medical chart and sent to their family physician. | Repeat visits to the emergency department; duplication of requests for diagnostic tests. | Setting: emergency department of a Jewish General Hospital in Montreal; an adult university teaching hospital with 637 beds. |

Table 3Clinical evidence summary: Integrated patient information systems versus no integrated patient information systems

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with No Integrated patient info system | Risk difference with Integrated patient info system (95% CI) | ||||

| Repeat visits to the ED within 14 days |

1616 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 1.09 (0.83 to 1.42) | Moderate | |

| 110 per 1000 | 10 more per 1000 (from 19 fewer to 46 more) | ||||

| Repeat visit to the ED within 28 days |

1616 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa due to risk of bias | RR 1.01 (0.81 to 1.25) | Moderate | |

| 168 per 1000 | 2 more per 1000 (from 32 fewer to 42 more) | ||||

| Duplication of diagnostic tests (between ED and the family physician office) |

1616 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 1.07 (0.61 to 1.9) | Moderate | |

| 27 per 1000 | 2 more per 1000 (from 11 fewer to 24 more) | ||||

| Duplication of diagnostic tests (in speciality consultations) |

1616 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 2.46 (1.09 to 5.56) | Moderate | |

| 10 per 1000 | 15 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 46 more) | ||||

- (a)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- (b)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID point, and downgraded by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed 2 MID points.