NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Selph SS, Skelly AC, Wasson N, et al. Physical Activity and the Health of Wheelchair Users: A Systematic Review in Multiple Sclerosis, Cerebral Palsy, and Spinal Cord Injury [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 Oct. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 241.)

Purpose

This systematic review summarizes the current evidence on the health effects of physical activity interventions in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), cerebral palsy (CP), and spinal cord injury (SCI). These three diverse conditions were chosen to represent individuals using a wheelchair or individuals who may benefit from using a wheelchair in the future. (“Wheeled mobility device” is sometimes used to encompass manual wheelchairs, motorized wheelchairs, and motorized scooters; this report uses the term wheelchair in this broad sense.) The review is focused on four Key Questions developed by the National Institutes of Health to inform a Pathways to Prevention Workshop. It is anticipated that the evidence synthesis on the health effects of physical activity intervention in people with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and spinal cord injury will be of ongoing interest to primary and specialty care providers, health researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders.

Background

For the general population, the health benefits of regular physical activity are well-recognized, as highlighted in 2008 and 2018 reports to the Department of Health and Human Services from the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee.1,2 In addition to a reduced risk of death, greater amounts of regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the risk of many of the most common and expensive diseases or conditions in the United States. Heart disease, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dementia, depression, postpartum depression, excessive weight gain, falls with injuries among the elderly, and breast, colon, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, stomach, and lung cancer are all less common among individuals who are or become more physically active.2 Physical activity may also help reduce the natural progression of disability in certain populations.3 In 2016 one in four noninstitutionalized U.S. adults (25.7%, representing an estimated 61.4 million people) reported having a physical and/or cognitive disability, and mobility was the most prevalent disability type (13.7% of the total).4 Newly released physical activity guidelines suggest adults with disability benefit from similar amounts of physical activity and muscle strengthening as the general population, although there may be some risk of injury for populations who are not accustomed to exercise.5 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services indicates that routine physical activity programs combining aerobic exercise with muscle strength and balance training improve fitness, function, and quality of life for individuals with physical disabilities.2 Less is known regarding specific health benefits of physical activity in people who use a wheelchair.

The various populations using wheelchairs are broad and poorly captured in the literature on physical activity, making a systematic review of all “wheelchair users” unfeasible. Additionally, some individuals may only need the use of a wheelchair some of the time—to cover longer distances or when experiencing a disease flare-up, for example. In order to generate a meaningful result from representative populations that reflect relatively consistent examples of why and how wheelchairs are being used, the analysis is focused on a broad but representative sample of potential wheelchair users—individuals with MS, CP, and SCI. Wheelchair users with these conditions have diverse underlying physiologic mechanisms, demographic profiles, respective physical limitations, and potential outcomes from regular physical activity. Understanding those differences assists in interpreting the literature relating to exercise among these diverse groups (Table 1).

SCI, MS, and CP have very different physiologic mechanisms (brain vs. spinal cord, degenerative vs. not) and demographic profiles (male vs. female predominance, childhood vs. adult onset). CP is usually present at birth. While the brain injury involved in CP can in general be relatively static, its early onset has effects on musculoskeletal development with functional sequela. In contrast, MS and SCI most often have onset after skeletal maturation is complete. MS can affect any central nervous system function, including vision, and can be progressive for many years. SCI does not affect motor or sensory systems above the level of the spinal cord lesion, sparing cerebral function, and the nervous system injury is usually static after the acute period.

While they are distinctly different in general etiology and pathophysiology, a common denominator for all three conditions is the involvement of the corticospinal tracts of the central nervous system, which results in an impaired central control and/or coordination of the peripheral muscles. This may lead to paralysis or reduced extremity muscle force and increased spasticity, which can greatly affect general mobility or coordinated movement such as posture and gait. The consequences on ambulation of this corticospinal tract injury exist along a functional spectrum, from fully ambulatory despite motor involvement, to a wide range of overlap of independent ambulation with intermittent wheelchair use, to full-time wheelchair use. Having MS, CP, or SCI is typically permanent and may result in decades of being sedentary if engaging in physical activity is not made a priority. The potential benefits in these populations may be even greater than in able-bodied people who are still mobile and who achieve some benefit of activity through performing ordinary activities in daily life such as pushing a grocery cart around a store, fixing dinner, or carrying a child up the stairs.

Many users of wheelchairs encounter psychological and physical barriers as well as limitations of access to preventive healthcare and appropriate physical activity programs intended to maintain healthy weight or body composition and physical fitness. The preventive benefits of regular exercise are particularly relevant for people with disabilities, who experience accelerated risk for the conditions known to be attenuated by regular exercise, such as obesity or increased body fat,13–15 dyslipidemia,16,17 and cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction,17,18 stroke,18–20 and death.8,18 Increased risk for morbidity and mortality may be due, in part, to the specific disease that limits mobility or leads to the use of a wheelchair, the treatment for the disease (e.g., steroids used to treat MS), and/or a sedentary lifestyle.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2017 report on the use of assistive technologies to enhance activity recommends that individuals who require wheeled and seated mobility devices receive regular evaluations of their physical condition.21 Evaluation should include at least annual assessments of the functioning and fitting of the devices, ergonomics and safety, ability to use the device, underlying disorder and secondary health conditions, functional needs, and the individual’s satisfaction. Access to appropriate care can facilitate education, linkage to activity resources, and encouragement of physical activity to help mitigate these risks.

People with disabilities face a number of barriers to exercise. Skill at using a wheelchair, fatigue, fear of falling, pain, heat sensitivity, negative bias/stigma,22 and conflicting information from providers have been listed as barriers to exercise among those with MS.23–27 Those with CP cite the need for caregiver support, prohibitive cost, and their medical condition as barriers to regular physical activity.28 Additionally, it can be challenging to find physical activities that a child with quadriplegic CP can do to improve strength or aerobic conditioning when motor control is insufficient. For individuals with SCI, concern about autonomic dysfunction, blood pressure and temperature regulation during exercise, may limit exercise participation,29,30 contributing to decreasing fitness levels with increasing time since injury.21 All wheelchair users are limited by lack of access to facilities, lack of transportation, and insufficient Americans with Disabilities Act compliance at community fitness centers.31–33 Individuals who infrequently need a wheelchair may not be completely comfortable with their wheelchair skills and therefore may not be active enough in participating in wheelchair sports or physical activities.34 Special equipment such as robot-assisted gait training (RAGT) or body weight support treadmill devices can be prohibitively difficult for people outside of major urban areas to access.

A review of Canadian community-based physical activity and wheelchair mobility programs points out a clear need for more programs, particularly those that assess long-term impact.32 Longer time since injury is associated with lower fitness levels in SCI with paraplegia.35 Decreased strength and muscle mass associated with aging increases risk for shoulder injury, and elderly wheelchair users need specific interventions to preserve mobility.36

Physical activity has been shown to improve body composition,37–39 cognition,40 glucose metabolism,39,41,42 and lipid profiles,39,43 and to decrease risk of morbidity and mortality in nondisabled people.38,44 Physical activity could similarly benefit those with disabilities. Recently published SCI guidelines recommend moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise at least twice weekly and strength exercise for each major functioning muscle group twice weekly.45 Verschuren et al. recommend aerobic sessions and strength training twice weekly for individuals with CP,46 while Halabchi et al. recommend aerobic exercises, strength training, and daily flexibility and stretching exercises for individuals with MS.47 In the past, exercise was not recommended for individuals with MS due to fear of worsening of symptoms.48 However, more recent evidence suggests that physical activity improves health outcomes in people with disabilities (including people with MS), and the updated 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans now recommend between 2.5 to 5 hours of moderate aerobic exercise weekly, or over 1 hour to 2.5 hours of vigorous aerobic exercise weekly, plus muscle strengthening activities, for people with physical disabilities.2 These guidelines suggest that children ages 3 through 5 years engage in physical activity throughout the day for normal growth and development and that school-aged children and adolescents receive 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, 60 minutes of muscle-strengthening activity, and 60 minutes of bone-strengthening activity at least 3 days a week. The guidelines do not offer recommendations regarding physical activity in children or adolescents with chronic disease or physical disability.

Scope and Key Questions

This systematic review summarizes and synthesizes current research on the specific benefits and potential harms of physical activity for people with MS, CP, and SCI, regardless of current use of a wheelchair. This topic was nominated by the Director of the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, and supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health Office of Disease Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health Medical Rehabilitation Coordinating Committee, which has representatives from 20 Institutes and Centers, along with other federal partners for a Pathways to Prevention (P2P) workshop to assess the benefits and harms of physical activity on the physical and mental health of adults, children, and adolescents using a wheelchair, or who may benefit from using a wheelchair in the future. In considering studies related to physical activity among three representative populations who consistently use, sometimes use, or who may, at some point in their lives, need to use a wheelchair as a result of neurological conditions of MS, CP, and SCI, we prioritized certain outcomes. These included long-term health outcomes of: cardiovascular mortality; myocardial infarction; stroke; development of diabetes; and new or increased need for a wheelchair. Other prioritized immediate health outcomes included: pulmonary function tests; VO2 peak; hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); bowel, bladder, and sexual function; decubitus ulcers; development of obesity; body mass index; weight; depression; quality of life; falls; function; autonomic dysreflexia; and spasticity. We evaluated outcomes of diverse physical activity interventions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and research methodologies to identify future research needs. The outcomes of pain and cognition were not included because it is expected that the magnitude of the literature involved would indicate that these topics should be separate reviews. Our overarching objective was to understand the specific benefits and potential harms of physical activity for those currently using or those who may benefit from using a wheelchair in the future and to identify domains for future research focus—ultimately improving health and quality of life.

Key Questions

- Key Question 1.

What is the evidence base on physical activity interventions to prevent obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions, including evidence on harms of the interventions in people with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or spinal cord injury who are at risk for or currently using a wheeled mobility device?

- What interventions have been studied?

- What outcomes have been studied?

- What inclusion/exclusion criteria have been used in studies?

- What other research methodologies (control/comparison group design, length of intervention, research setting) have been used?

- Key Question 2.

What are the benefits and harms of physical activity interventions for people with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or spinal cord injury who are at risk for or currently using a wheeled mobility device?

- Does physical activity improve clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, overweight or obesity, mental health, or sexual function?

- Does physical activity improve intermediate outcomes such as physical fitness, obesity, or bone density?

- Does physical activity reduce the harms of immobility, such as incidence of decubitus ulcer, urinary tract infection, bowel dysfunction, or autonomic dysfunction?

- Does physical activity decrease the risk for adverse outcomes of disorders associated with wheeled mobility device use, such as spasticity, autonomic dysreflexia, or muscle contractures?

- What are the harms of physical activity, such as injuries that are associated with wheeled mobility device use (e.g., falls, tips, overuse injuries)?

- Do the benefits or harms of physical activity vary by the location of the intervention (e.g., home, community, clinic), amount of training or instruction (e.g., no training, some training, all physical activity sessions with training), or level of supervision (e.g., inpatient, telehealth)?

- Key Question 3.

What are the patient factors that may affect the benefits and harms of physical activity in patients with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or spinal cord injury who are at risk for or currently using a wheeled mobility device?

- Do the benefits and harms of physical activity vary by age, sex, or race/ethnicity?

- Do the benefits and harms of physical activity vary by primary disease or injury that led to wheelchair use?

- Key Question 4.

What are methodological weaknesses or gaps that exist in the evidence to determine benefits and harms of physical activity in patients with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or spinal cord injury who are at risk for or currently using a wheeled mobility device?

- What types of studies supported conclusions in Key Questions 2 and 3?

- What are the major weaknesses in study designs?

- What would improve ability of future research to address the Key Questions?

PICOTS

The Methods section provides details on the Populations, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Timing, Settings, and Study Designs (PICOTS) inclusion and exclusion criteria. An overview of the PICOTS for this review follows.

Populations

- Include for Key Question (KQ) 1, KQ2, and KQ3: Patients with MS, CP, or SCI; in studies of mixed populations, at least 80 percent will be individuals with MS, CP, and/or SCI. All ages included.

- Exclude: Other populations.

Interventions

- Include for all KQs: Any gross motor intervention with a defined period of directed physical activity that is expected to increase energy expenditure. Intervention must have a minimum of 10 sessions on 10 different days of activity in a supervised individual or group setting. Include: aerobic exercise, strength training, standing, balance, flexibility, and combination interventions.

- Exclude: Unobserved physical activity; parent or caregiver observed interventions; interventions that do not target the whole body (e.g., interventions to improve reaching or to improve the function of one joint, partial body vibration); single studies of one intervention.

Comparators

- Include for all KQs: Between-group comparisons with no physical activity or other types of physical activity or a behavioral intervention with a physical activity outcome.

- Exclude: Comparisons to other active comparators such as drug therapy; pre-post studies with only one group of participants.

Outcomes

- For KQ2 and KQ3: Benefits and harms of physical activity including: (a) clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, mental health, obesity/overweight, and sexual function; (b) intermediate outcomes such as physical fitness, HbA1c, bone density, and resting heart rate; and (c) subgroup differences based on location of intervention (e.g., home, community, clinic), level of instruction or training (e.g., no training, some training, all physical activity sessions with training), and level of supervision (e.g., inpatient, telehealth).

- For KQ4: Major weakness in study design, items that improve the ability to address the KQs.

- Exclude: Outcomes not used to make clinical decisions (e.g., estradiol level, muscle thickness).

Timing

- Include for all KQs: At least 10 sessions of physical activity spread out over no fewer than 10 days.

- Exclude: Acute spinal cord trauma stabilization period, immediate postoperative period (e.g., after surgeries to improve musculoskeletal function in CP).

Setting

- Include for all KQs: Any U.S. or U.S.-applicable study, including clinic, home (provided physical activity is observed by healthcare or research staff), or community setting (e.g., gym or athletic class).

- Exclude: Non-U.S.-applicable setting.

Study Designs

- Include for all KQs: Clinical trials and observational studies (cohort studies and case-control studies).

- Include for all KQs: Studies with the following minimum sample sizes analyzed: MS (n=30), CP (n=20), SCI (n=20).

- Include for all KQs: Studies published since 2008; systematic reviews published since 2014.

- Include, if needed, due to lack of clinical trials or controlled observational studies: Pre-post studies.

- Exclude: Case report, case series, and cross-sectional studies.

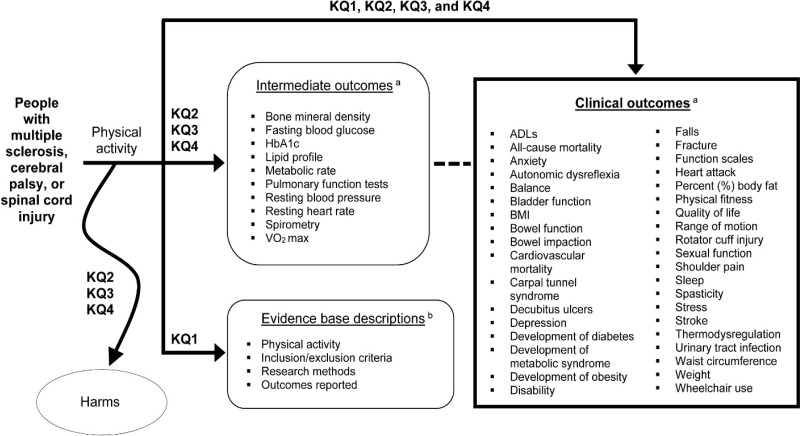

Analytic Framework

The analytic framework (Figure 1) illustrates the relationship between the KQs and the outcomes for this review. The figure indicates the questions associated with intermediate outcomes, descriptions of the evidence base, clinical outcomes, and harms. The complete PICOTS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies in this review appear in the Methods section.

Organization of Report

This report is organized by sections. Each represents either a main section of the report (i.e., Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion) or a Key Question.

Key Question 1 provides an overview of the evidence base of included studies as well as identification of studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria of this report.

For Key Question 2 we present the results of the benefits and harms of physical activity interventions for clinical outcomes of interest (Figure 1), subdivided by intervention categories of aerobic exercise, postural control, strength interventions, and multimodal interventions. Interventions specific to each of these categories are indicated with a brief description of the subtype of exercise, key points specific to that intervention, and detailed results are organized by the specific population of MS, CP, and SCI. Studies that reported on only one or more intermediate outcomes (Figure 1) are reported separately.

The Key Question 2 intervention categories include:

- Aerobic exercise interventions:

- Aerobics

- Aquatics

- Cycling

- Hand cycling

- RAGT

- Treadmill

- Postural control interventions:

- Balance exercise

- Hippotherapy

- Tai Chi

- Motion gaming

- Whole body vibration

- Yoga

- Strength interventions:

- Muscle strength exercise

- Multimodal interventions:

- Progressive resistance or strengthening exercise plus aerobics and/or postural control interventions

For Key Question 2 the general effects of exercise were also assessed:

- All exercise interventions:

- Interventions with sufficient outcomes data to be analyzed independent of population or intervention category

Key Question 3 evaluates patient factors that may affect the benefits and harms of physical activity, and Key Question 4 reports the methodological weaknesses or gaps in the evidence base.

Figures

Figure 1Analytic framework for physical activity and the health of wheelchair users with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and spinal cord injury

Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living; BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; KQ = Key Question; VO2 max = maximal oxygen uptake

a Outcomes are specified in the Methods section

b Studies that evaluate prevention of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and harms

Tables

Table 1Characteristics, causes, and prevalence of multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and spinal cord injury

| Causes, Prevalence, and Characteristics | Cerebral Palsy | Multiple Sclerosis | Spinal Cord Injury |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Traumatic injury to a developing brain before, during, or after birth | Progressive autoimmune disease of the central nervous system with variable disease patterns; 10% primary progressive and others progressive after initial relapse and remitting course | Usually traumatic cord injury (motor vehicle accidents, falls, violence, sports); nervous system above the lesion is intact |

| Prevalence | 1.5 to more than 4 per 1,000 live births; males 30% greater than females; 764,000 children and adults living with CP in the United States6 | Nearly 1 million people in the United States have MS; average age onset 30 years old and females 2 to 3 times males7 | Estimated 282,000 in the United States with SCI; recent evidence puts the average age 43 years old; 78% male8,9 |

| Mobility | 40% limitations in walking and 30% use walkers or wheelchairs | Mobility limitations generally occur later in disease course; after 45 years of disease, on average 76% of individuals require ambulatory aid and 52% bilateral assistance10 | Variable and depends on level and completeness of injury; generally stable after injury and initial rehabilitation |

| Associated morbidity | 40% of children with CP have intellectual disability, 35% epilepsy, and more than 15% had vision impairment | Sequela of immune suppression including urinary and respiratory infections, seizures, other autoimmune diseases, visual abnormalities, ataxia11 | Respiratory complications, thromboembolism, autonomic dysreflexia, orthostatic hypotension, bladder dysfunction, neurogenic bowel, spasticity, pain, pressure ulcers12 |

| Usual intent of physical activity | Increase mobility and overall level of function as component multimodality efforts during childhood development | Maintain mobility and attenuate limitations of progressive disease; because those with MS often have normal life expectancies the benefits of exercise for the general population would also apply | Maximize functional abilities; recreation; because long-term sequela SCI better prevented/managed, longer term health benefits of regular exercise also are relevant |

Abbreviations: CP = cerebral palsy; MS = multiple sclerosis; SCI = spinal cord injury