Clinical Description

NFIX-related Malan syndrome (MALNS) was first reported in three individuals with overgrowth and heterozygous pathogenic variants in NFIX in 2010 [Malan et al 2010]. Since that time, at least 100 individuals have been identified with MALNS [Priolo et al 2012, Yoneda et al 2012, Klaassens et al 2015, Gurrieri et al 2015, Martinez et al 2015, Jezela-Stanek et al 2016, Oshima et al 2017, Priolo et al 2018, Hancarova et al 2019, Sihombing et al 2020, Tabata et al 2020, Langley et al 2022, Macchiaiolo et al 2022]. The following description of the phenotypic features associated with this condition is based on these reports.

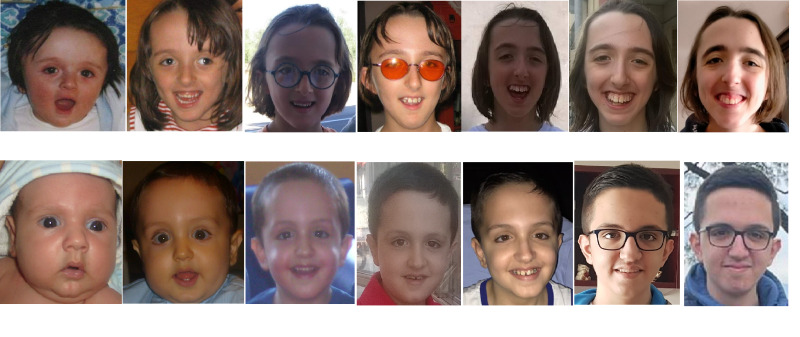

Facial features. Distinctive facial features are generally present in all affected individuals identified to date. The facial features include a long and triangular face, high anterior hair line with prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge, deep-set eyes, downslanted palpebral fissures, short nose with anteverted nares and upturned tip, long philtrum, small mouth that is often held open, thin vermilion of the upper lip, an everted lower lip, and a prominent chin (see ). Other less frequent features are high-arched palate, dental crowding, sparse hair, loose and soft skin, and facial asymmetry [Priolo et al 2018, Alfieri et al 2022, Macchiaiolo et al 2022].

Growth

Developmental delay (DD) and intellectual disability (ID). Cognitive impairment and DD are invariably present and may range from moderate to severe. Rarely, mild ID has been reported.

Typically, affected individuals show both low cognitive and adaptive functioning, with communication skills being the most affected.

The level of intellectual impairment generally remains stable throughout life.

A dedicated diagnostic battery of tests has been proposed to carefully assess the impairment in different domains (for a full review of the battery of tests recommended, see

Alfieri et al [2022] and

Alfieri et al [2023]).

Aadaptive functioning is usually lower than normal, generally ranging from moderately to severely impaired, with communication skills the most affected.

Other neurodevelopmental features

Hypotonia. At least 65% of individuals with MALNS have been reported to have hypotonia. This finding may cause, together with DD, feeding difficulties and drooling in infancy. Hypotonia may persist during childhood and slowly improve with time.

Autonomic findings. Recurring autonomic signs have been reported in at least 25% of affected individuals. Symptoms may be subtle or nonspecific (e.g., vomiting/nausea, dizziness, fainting). These signs may be occasional or triggered by external causes (stress, anxiety, provoking situations).

The same signs, sometimes associated with gait disturbances (e.g., broad-based gait, toe-walking), have also been occasionally described in affected individuals with Chiari I malformations, but they may be also observed in individuals with MALNS who do not have Chiari I malformations. For this reason, individuals with MALNS should be first assessed for Chiari I malformations through neuorimaging and then for other causes (e.g., cardiac/otologic evaluation) of these nonspecific symptoms.

Epilepsy. Seizures and electroencephalogram (EEG) anomalies are common and more frequently observed among individuals with continuous gene deletions that include NFIX and surrounding genes. Individuals with NFIX intragenic pathogenic variants are prone to develop nonspecific EEG anomalies, which usually do not require anti-seizure medication (ASM) [Macchiaiolo et al 2022]. The exact types and severity of epilepsy in individuals with this condition have not been well characterized to date.

Neurobehavioral/psychiatric manifestations affect most individuals with MALNS. Behavioral problems characterized by a specific anxious profile are seen in more than 80% of affected individuals. Anxiety does not appear to affect individuals in any specific age range but may worsen over time.

The most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities include generalized anxiety disorder; separation anxiety with specific phobias; attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; and behavioral issues (e.g., impaired socialization) that may resemble those of individuals with autism but are different from classic autistic behavior.

Some affected individuals may be given a clinical diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder primarily because of their expressive language difficulties. However, most affected individuals do not have true impairment in social interactions outside of their deficient communication skills [Mulder et al 2020, Alfieri et al 2022, Alfieri et al 2023].

Additional neuropsychiatric hallmarks include difficulty with visuomotor integration; hypersensitivity to visual and auditory stimuli (noise hypersensitivity and photophobia), both of which may contribute to psychopathology; and challenging behaviors with panic crises and, rarely, outbursts of hetero-aggression and self-injurious behavior.

Neuroimaging. Brain MRI abnormalities are identified in at least half of individuals with MALNS. Ventricular dilatation and corpus callosum hypoplasia are the most frequent findings, present in 8/16 (50%) individuals reported by Macchiaiolo et al [2022]. Chiari I malformation has been identified in 6/16 (38%) affected individuals. In the study by Macchiaiolo et al [2022], about 25% of affected individuals had various degrees of optic nerve hypoplasia; however, data from patient registries suggest that this latter figure might be an underestimate [Sanford CoRDS patient registry for Malan syndrome].

Musculoskeletal features may include the following:

Slender body habitus (almost all individuals)

Advanced bone age (at least 76%)

Scoliosis (75%)

Hyperkyphosis or hyperlordosis (~30%)

Pes planus (69%)

Pectus anomaly (excavatum, carinatum, or mixed) (63%)

Long bone fracture

Individuals with MALNS have a slightly increased risk of bone fractures during childhood as compared to the general population [

Macchiaiolo et al 2022].

Rarely, mild osteopenia has been identified by DXA scan, which quickly resolved after vitamin D

3 supplementation (see

Management) [

Macchiaiolo et al 2022, Sanford CoRDS patient registry for Malan syndrome].

Ophthalmologic findings, including strabismus and refractive errors (such as myopia, hypermetropia, and astigmatism), occur with an overall frequency of about 75%. About 70% of affected individuals have blue sclerae. There is some evidence to suggest that adults with MALNS may be at risk for late-onset optic nerve degeneration. Other findings may include:

Cardiovascular anomalies have been reported in a small proportion of individuals with MALNS. Four individuals with aortic root dilatation and one with pulmonary artery dilatation have been reported [Nimmakayalu et al 2013, Oshima et al 2017, Priolo et al 2018]. There is limited data available on aortic root z scores or on whether aortic dilation was static or progressive; however, one affected adult experienced progressive aortic dilation and dissection at age 38 years [Oshima et al 2017]. Minor cardiac anomalies, such as low-grade mitral regurgitation, have been frequently observed [Macchiaiolo et al 2022]. Other major cardiac findings have been reported in a minority of reported individuals.

Gastrointestinal issues. Isolated hepatomegaly has been observed in about one quarter of individuals with MALNS either during childhood or adulthood. It is not generally associated with liver dysfunction.

Different degrees of constipation, sometimes requiring pharmacologic therapy (see Management), have been observed in almost half of individuals.

Hearing. Two individuals with MALNS have been reported with bilateral moderate-to-severe sensorineural hearing impairment [Priolo et al 2018, Sanford CoRDS patient registry for Malan syndrome]. Many individuals with this condition are sensitive to noise (see Neurobehavioral/psychiatric manifestations above).

Genitourinary. A minority of affected males have had cryptorchidism. Renomegaly might be observed as an incidental finding.

Malignancy. To date, one individual with rib osteosarcoma and another with Wilms tumor have been reported (an overall prevalence of malignancy of about 2%). Therefore, MALNS appears to be in the same low risk group as Sotos syndrome and Weaver syndrome with respect to a low likelihood of developing cancer [Villani et al 2017, Priolo et al 2018, Brioude et al 2019, Macchiaiolo et al 2022]. Therefore, no tumor screening protocols have been proposed or recommended for individuals with MALNS.

Prognosis. It is unknown whether the life span in MALNS is abnormal. Two reported individuals are alive at age 40 and 60 years, respectively [M Priolo, personal observation], demonstrating that survival into adulthood is possible. Since many adults with disabilities have not undergone advanced genetic testing, it is likely that adults with this condition are underrecognized and underreported.