CASRN: 83905-01-5

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Because of the low levels of azithromycin in breastmilk and use in infants in higher doses, it would not be expected to cause adverse effects in breastfed infants. Monitor the infant for possible effects on the gastrointestinal flora, such as vomiting, diarrhea, candidiasis (thrush, diaper rash). Unconfirmed epidemiologic evidence indicates that the risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis might be increased by maternal use of macrolide antibiotics during the first two weeks of breastfeeding, but others have questioned this relationship. In one study, a single dose of azithromycin given during labor to women who were nasal carriers of pathogenic Staphylococcus and Streptococcus reduced the counts of these bacteria in breastmilk, but increased the prevalence of azithromycin-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae in breastmilk.

Maternal use of an eye drop that contains azithromycin presents negligible risk for the nursing infant. To substantially diminish the amount of drug that reaches the breastmilk after using eye drops, place pressure over the tear duct by the corner of the eye for 1 minute or more, then remove the excess solution with an absorbent tissue.

Drug Levels

Maternal Levels. A woman who was 1 day postpartum was given 1 g of azithromycin orally. Forty-eight hours later her milk azithromycin was 0.64 mg/L. An oral regimen of 500 mg daily for 5 days was started, and more milk samples were obtained. One hour after the first dose, breastmilk contained 1.3 mg/L and 30 hours after the third dose milk contained 2.8 mg/L.[1] Because of the slow clearance and accumulation of azithromycin, it is difficult to interpret these milk levels. The dose that the infant would receive in milk would gradually increase for several days because maternal blood levels would increase until steady-state had been reached. If the level of 2.8 mg/L is used as an approximate trough level, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive a minimum of 0.42 mg/kg daily compared to the dose of 5 to 10 mg/kg daily used in infants of 6 months and over.

In a study of 30 women given azithromycin 500 mg intravenously 15, 30 or 60 minutes prior to incision for cesarean section, 8 women extracted breastmilk by pump. Breastmilk (colostrum) samples were obtained between 12 and 48 hours after the dose. Azithromycin persisted in breastmilk up to 48 hours after a dose with a median breastmilk concentration of 1713 mcg/L at a median of 30.7 hours after the dose. A computer model was constructed and the calculated median half-life in breastmilk was 15.6 hours, which was longer than the maternal serum half-life of 6.7 hours. Using the model, the authors calculated that with continuous administration of 500 mg every 12 hours, steady-state would occur in 3 days and an exclusively breastfed infant would receive 0.1 mg/kg daily.[2]

Breastmilk azithromycin concentrations were measured in 20 Gambian women after receiving a single 2 gram oral dose of azithromycin during labor. Breastmilk samples were collected on days 2 and 6 postpartum as well as 2 and 4 weeks postpartum (80 samples total, of which 78 were used). Milk concentrations were entered into a previously existing population model of azithromycin pharmacokinetics in pregnant women. The median cumulative infant dosage over the first 28 days postpartum was estimated to be 3.9 mg/kg (0.6 mg/kg daily) for the single 2 gram maternal dose. The authors also simulated a maternal dosage regimen of 1 gram daily for 3 days and estimated an infant dosage of 7.8 mg/kg (1.2 mg/kg daily). These values translate to a weight-adjusted dosage of 2.2% and 2.9% of the maternal dosage, respectively. The median absolute dosages are considerably less than the reported infant dosages of 50 to 60 mg/kg; however, simulations indicated that the maximum dosage that an infant might receive is 32 and 63 mg/kg, respectively, of the standard infant dosage.[3]

Infant Levels. Relevant published information was not found as of the revision date.

Effects in Breastfed Infants

A cohort study of infants diagnosed with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis found that affected infants were 2.3 to 3 times more likely to have a mother taking a macrolide antibiotic during the 90 days after delivery. Stratification of the infants found the odds ratio to be 10 for female infants and 2 for male infants. All the mothers of affected infants nursed their infants. Most of the macrolide prescriptions were for erythromycin, but only 7% were for azithromycin. However, the authors did not state which macrolide was taken by the mothers of the affected infants.[4]

A retrospective database study in Denmark of 15 years of data found a 3.5-fold increased risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the infants of mothers who took a macrolide during the first 13 days postpartum, but not with later exposure. The proportion of infants who were breastfed was not known, but probably high. The proportion of women who took each macrolide was also not reported.[5]

A study comparing the breastfed infants of mothers taking amoxicillin to those taking a macrolide antibiotic found no instances of pyloric stenosis. However, most of the infants exposed to a macrolide in breastmilk were exposed to roxithromycin. Only 10 of the 55 infants exposed to a macrolide were exposed to azithromycin. Adverse reactions occurred in 12.7% of the infants exposed to macrolides which was similar to the rate in amoxicillin-exposed infants. Reactions included rash, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and somnolence.[6]

Eight women who were given azithromycin 500 mg intravenously 15, 30 or 60 minutes prior to incision for cesarean section breastfed their newborn infants. No adverse events were noted in their infants.[2]

Two meta-analyses failed to demonstrate a relationship between maternal macrolide use during breastfeeding and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.[7,8]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

In a double-blind, controlled study in Gambia, women who were nasopharyngeal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae or group B streptococcus were given a single 2 gram dose of azithromycin during labor. Milk samples from women who received azithromycin had 9.6% prevalence of carriage of the organisms compared to 21.9% in women who received placebo. Nasopharyngeal carriage in mothers and infants was also reduced on day 6 postpartum.[9] However, a later analysis found oral intrapartum azithromycin did not reduce carriage of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae and was associated with an increase in the prevalence of azithromycin-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates in breastmilk.[10]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

References

- 1.

- Kelsey JJ, Moser LR, Jennings JC, et al. Presence of azithromycin breast milk concentrations: A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:1375-6. [PubMed: 8178871]

- 2.

- Sutton AL, Acosta EP, Larson KB, et al. Perinatal pharmacokinetics of azithromycin for cesarean prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:812.e1-6. [PMC free article: PMC4612366] [PubMed: 25595580]

- 3.

- Salman S, Davis TM, Page-Sharp M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of transfer of azithromycin into the breast milk of African mothers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;60:1592-9. [PMC free article: PMC4775927] [PubMed: 26711756]

- 4.

- Sørensen HT, Skriver MV, Pedersen L, et al. Risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after maternal postnatal use of macrolides. Scand J Infect Dis 2003;35:104-6. [PubMed: 12693559]

- 5.

- Lund M, Pasternak B, Davidsen RB, et al. Use of macrolides in mother and child and risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g1908. [PMC free article: PMC3949411] [PubMed: 24618148]

- 6.

- Goldstein LH, Berlin M, Tsur L, et al. The safety of macrolides during lactation. Breastfeed Med 2009;4:197-200. [PubMed: 19366316]

- 7.

- Abdellatif M, Ghozy S, Kamel MG, et al. Association between exposure to macrolides and the development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr 2019;178:301-14. [PubMed: 30470884]

- 8.

- Almaramhy HH, Al-Zalabani AH. The association of prenatal and postnatal macrolide exposure with subsequent development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr 2019;45:20. [PMC free article: PMC6360705] [PubMed: 30717812]

- 9.

- Roca A, Oluwalana C, Bojang A, et al. Oral azithromycin given during labour decreases bacterial carriage in the mothers and their offspring: A double-blind randomized trial. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:565.e1-9. [PMC free article: PMC4936760] [PubMed: 27026482]

- 10.

- Getanda P, Bojang A, Camara B, et al. Short-term increase in the carriage of azithromycin-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in mothers and their newborns following intra-partum azithromycin: A post hoc analysis of a double-blind randomized trial. JAC-Antimicr Res 2021;3:dlaa128. [PMC free article: PMC8210243] [PubMed: 34223077]

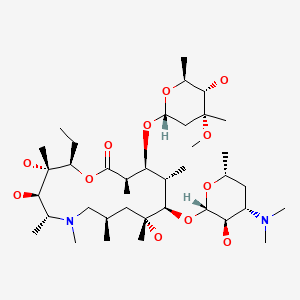

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Azithromycin

CAS Registry Number

83905-01-5

Drug Class

Breast Feeding

Lactation

Milk, Human

Anti-Bacterial Agents

Anti-Infective Agents

Macrolides

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

Publication Details

Publication History

Last Revision: August 15, 2024.

Copyright

Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Publisher

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda (MD)

NLM Citation

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Azithromycin. [Updated 2024 Aug 15].