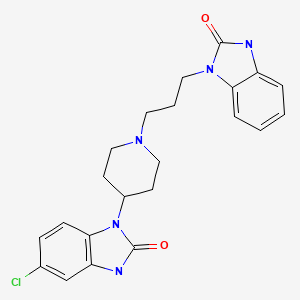

CASRN: 57808-66-9

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Domperidone is not approved for marketing in the United States by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but is available in other countries. Domperidone may also be available from some compounding pharmacies and via the internet in the US. The quality of such products cannot be assured, and the FDA has warned against their use.[1]

Data available from 4 small studies on the excretion of domperidone into breastmilk are somewhat inconsistent, but infants would probably receive less than 0.1% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage, even at high maternal doses. No adverse effects have been found in a limited number of published cases of breastfed infants whose mothers were taking domperidone.

Domperidone is sometimes used as a galactogogue to increase milk supply.[2,3] and has been used in induced lactation by adoptive and transgender women.[4-11] Galactogogues should never replace evaluation and counseling on modifiable factors that affect milk production.[12,13] Most mothers who are provided instruction in good breastfeeding technique and breastfeed frequently are unlikely to obtain much additional benefit from domperidone. Several meta-analyses of domperidone use as a galactogogue in mothers of preterm infants concluded that domperidone can increase milk production acutely in the range of 90 to 94 mL daily.[3,14,15] Other reviewers concluded that improvement of breastfeeding practices seems more effective and safer than off-label use of domperidone.[16,17] One retrospective study found that breastmilk feeding rates at discharge remained consistently lower in very preterm (<32 weeks gestation) infants of women dispensed domperidone than those who were not prescribed domperidone.[18]

Domperidone has no officially established dosage for increasing milk supply. Most published studies have used domperidone in a dosage of 10 mg 3 times daily for 4 to 10 days. Two small studies found no statistically significant additional increase in milk output with a dosage of 20 mg 3 times daily compared to a dosage of 10 mg 3 times and that women who failed to respond to the low dosage did not respond to the higher dosage.[19,20] Dosages greater than 30 mg daily may increase the risk of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in patients receiving domperidone,[21] although some feel that the risk is less in nursing mothers because of their relatively younger age.[22] Large database retrospective cohort studies in Canada found an increase in the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, but some confounders make the results subject to question.[23,24] In one case, domperidone use uncovered congenital long QT syndrome in a woman who developed loss of consciousness, behavioral arrest, and jerking while taking domperidone.[25] Mothers with a history of cardiac arrhythmias should not receive domperidone and all mothers should be advised to stop taking domperidone and seek immediate medical attention if they experience signs or symptoms of an abnormal heart rate or rhythm while taking domperidone, including dizziness, palpitations, syncope or seizures.[21]

Maternal side effects of domperidone reported in galactogogue studies and cases reported to the FDA include dry mouth, headache, dizziness, nausea, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, palpitations malaise, and shortness of breath. Some of these were more frequent with dosages greater than with 30 mg daily.[19,20,26-28] Surveys of women taking domperidone for lactation enhancement found gastrointestinal symptoms, breast engorgement, weight gain, headache, dizziness, irritability, dry mouth and fatigue were the most common side effects reported.[29-31] One mother taking domperidone 20 mg three times daily as a galactogogue for feeding her adoptive daughter developed obsessional thoughts with adjustment disorder. This manifested as thoughts of killing her daughter. Stopping domperidone and instituting duloxetine therapy resulted in remission over a 10-month period.[32]

Canadian health authorities found an association between the abrupt discontinuation or tapering of domperidone used for lactation stimulation and the development of psychiatric adverse events.[33] Canadian labeling warns against use of domperidone doses greater than 30 mg daily for longer than 4 weeks. Drug withdrawal symptoms consisting of insomnia, anxiety, and tachycardia were reported in a woman taking 80 mg of domperidone daily for 8 months as a galactogogue who abruptly tapered the dosage over 3 days.[34] Another mother took domperidone 10 mg three times daily for 10 months as a galactagogue and stopped abruptly. After discontinuation, she experienced severe insomnia, severe anxiety, severe cognitive problems and depression.[35] A third postpartum woman began domperidone 90 mg daily, increasing to 160 mg daily to increase her milk supply. Because her milk supply did not improve, she stopped nursing at 14 weeks and began to taper the domperidone dosage by 10 mg every 3 to 4 days. Seven days after discontinuing domperidone, she began experiencing insomnia, rigors, severe psychomotor agitation, and panic attacks. She restarted the drug at 90 mg daily and tapered the dose by 10 mg daily each week. At a dose of 20 mg daily, the same symptoms recurred. She required sertraline, clonazepam and reinstitution of domperidone at 40 mg daily, slowly tapering the dose over 8 weeks. Three months were required to fully resolve her symptoms.[36] In a fourth case, a mother took domperidone 20 mg four times daily for 9 months to stimulate breastmilk production. She stopped breastfeeding and domperidone at that time. Two weeks later, she presented with insomnia, anxiety, nausea, headaches and palpitations. The drug was restarted at a dosage of 20 mg three times daily and began to taper the daily dosage by 10 mg every week, but after one week she complained of insomnia. Tapering was reduced to 5 mg every week, but whenever she stopped the drug, symptoms returned. She was able to discontinue domperidone after tapering the daily dosage by 2.5 mg weekly over 10 months.[37] A fifth case of a mother with a history of bipolar disorder and major depression developed severe anxiety, a recurrence of depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder 6 days after abruptly discontinuing domperidone 120 mg daily that she was taking as a galactogogue. Three days later, she restarted domperidone 120 mg daily and tapered her daily dose by 10 mg at weekly intervals. She took no other medications. Two weeks after discontinuing domperidone, she had signs of only mild mood disorder.[38] Three patients were reported to have severe symptoms of withdrawal (depression, reemergence of obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, poor concentration, loss of libido, lack of energy, suicidality, hot flashes, night sweats, hair thinning, and dry eyes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and decreased appetite) after stopping domperidone as a galactogogue. Dosages ranged from 90 to 150 mg daily for 5 to 32 weeks. Dosages required a slow hyperbolic tapering over a period of several months to fully discontinue the drug.[39]

Drug Levels

Maternal Levels. Thirty breastmilk samples were obtained from 6 mothers taking domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily and 28 milk samples were obtained from 5 mothers taking domperidone 20 mg 3 times daily. Average concentrations of the drug in breastmilk were 0.28 mcg/L with the lower dosage and 0.49 mcg/L with the higher dosage. The authors estimated that a fully breastfed infant would receive daily dosages of 0.04 and 0.07 mcg/kg daily, respectively, at these maternal dosages. The estimated weight-adjusted maternal dosages were 0.012% and 0.009%, respectively.[19]

A double-blind, controlled trial compared two dosages of domperidone for increasing milk supply in mothers of preterm infants. Mothers received either 10 mg or 20 mg three times daily. Drug concentrations in breastmilk were measured once between days 10 and 15 three hours after a dose. Milk domperidone concentrations were 3.4 mcg/L with the 10 mg dose (n = 4) and 6.9 mcg/L with the 20 mg dose (n = 3).[20]

A woman was taking domperidone 40 mg 4 times daily for 7 months to enhance milk production. She submitted 5 milk samples over a 24-hour period for analysis. Using the average of the concentration values resulted in an estimated daily infant dosage of 1 mcg/kg and a relative infant dose of 0.05%. Using the highest value of 8.4 mcg/L, the RID was 0.06%.[40]

Infant Levels. Relevant published information was not found as of the revision date.

Effects in Breastfed Infants

One paper reported 2 studies. In one, 8 women received domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily from day 2 to 5 postpartum. In the other, 9 women received domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily for 10 days from week 2 postpartum. No side effects were reported in any of the breastfed (extent not stated) infants.[41,42]

Eleven women took domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily for 7 days to increase the supply of pumped milk for their preterm neonates. No side effects were reported in their infants.[43]

In a study of 90 mothers who received domperidone 10 mg three times daily for 2 or 4 weeks while providing milk for their preterm infants, there was no apparent difference in the frequency or types of adverse events that occurred in their infants, whether taking the active drug or placebo.[44]

A transgender woman took and spironolactone 50 mg twice daily to suppress testosterone, domperidone 10 mg three times daily, increasing to 20 mg four times daily, oral micronized progesterone 200 mg daily and oral estradiol to 8 mg daily and pumped her breasts 6 times daily to induce lactation. After 3 months of treatment, estradiol regimen was changed to a 0.025 mg daily patch and the progesterone dose was lowered to 100 mg daily. Two weeks later, she began exclusively breastfeeding the newborn of her partner. Breastfeeding was exclusive for 6 weeks, during which the infant's growth, development and bowel habits were normal. The patient continued to partially breastfeed the infant for at least 6 months.[4]

A transgender woman was taking spironolactone 100 mg twice daily, progesterone 200 mg daily and estradiol 5 mg daily. She was started on domperidone 10 mg three times daily to increase milk supply. She was able to pump 3 to 5 ounces of milk daily one month after starting. The dose of domperidone was increased to 30 mg three times daily after 8 weeks because of a decreased milk supply. Her milk supply returned to 3 to 5 ounces of milk daily. By 6 months, her milk supply had decreased to about 5 mL daily, even though her serum prolactin was still elevated.[45]

A transgender woman had been taking estradiol 2 mg twice daily for 14 years. She began taking domperidone 10 mg four times daily and progesterone 100 mg daily 107 days prior to her partner’s due date. At the same time, the estradiol dosage was increased to 4 mg twice daily. At 94 days prior to the due date, the domperidone dosage was increased to 20 mg four times daily, the progesterone dose was increased to 200 mg daily and estrogen was changed to transdermal estradiol 25 mcg daily. Progesterone was discontinued 34 days prior to the due date. She pumped and stored milk beginning at 34 days prior to the due date and by 27 days postpartum, she was breastfeeding the infant twice daily, expressing 150 mL of milk daily and was able to decrease the domperidone dosage to 20 mg three times daily. Lower dosages reduced milk supply.[7]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

Domperidone increases serum prolactin in lactating and nonlactating women.[19,46-48] This effect is thought to be caused by the drug's antidopaminergic effect. In nonpregnant women, domperidone is less effective than the same dose of oral metoclopramide in raising serum prolactin; however, in multiparous women their effects are similar.[46,48] Domperidone has caused galactorrhea in nonpregnant women and in one male, nonbreastfed infant.[49-56]

One paper, which was published twice in 2 different journals,[41,42] reported two separate small studies. In the first study, 15 women with a history of defective lactogenesis were given either oral domperidone 10 mg (n = 8) or placebo (n = 7) 3 times daily from day 2 to 5 postpartum. The patients were apparently not randomized and blinding was not mentioned in the paper. No instruction or support in breastfeeding technique was provided. The groups had similar serum prolactin levels at the start of the study. Baseline serum prolactin levels were higher in the treated women from day 3 to 5 postpartum. Suckling-induced serum prolactin increases were higher in the treated women than in the placebo group from day 2 postpartum onward. Milk yield was calculated by weighing the infants before and after each nursing for 24 hours. Increase in milk yield were greater in the treated mothers from day 2 onward; however, the lower average milk yield in the placebo group was due to 3 women with very low milk output. Average infant weight gain was correspondingly greater in the treated group. At 1 month postpartum, all treated mothers were nursing well, but 5 of 7 untreated mothers had inadequate (not defined) lactation. No correlation was found between baseline serum prolactin or the increase in prolactin and milk production.

In the same paper(s), 17 primiparous women who had insufficient lactation (30% below normal) at 2 weeks postpartum were studied using the same methodology as above. Mothers were given either oral domperidone 10 mg (n = 9) or placebo (n = 8) 3 times daily for 10 days. The groups did not have significantly different serum prolactin levels at the start of the study. Serum prolactin levels were higher in the treated than untreated women from day 2 onward and milk production was higher in the treated group from day 4 onward. At the end of the study no untreated woman had an increase in milk supply from day 1. One month after the beginning of the study, all treated women had adequate milk production. No correlation was found between serum prolactin and milk production.[41]

One well-designed, but small trial was reported with domperidone. Twenty women who were pumping milk with a good quality electric pump for their preterm infants were given either oral domperidone 10 mg (n = 11) or placebo (n = 9) 3 times daily for 7 days in a randomized, double-blind, trial. The mothers averaged 32 to 33 days postpartum. All had failed to produce sufficient milk for their infant after extensive counseling by lactation consultants. By day 5 of therapy, the serum prolactin levels of the treated mothers had increased by 119 mcg/L in the treated group compared to 18 mcg/L in the placebo group. Serum prolactin decreased to baseline levels in both groups 3 days after discontinuation of the study medications. Although the (partially imputed) baseline milk production was greater in the domperidone group (113 mL daily) than in the placebo group (48 mL daily), the average daily increases in milk production on days 2 to 7 were 45% (to 184 mL) and 17% (to 66 mL) in the domperidone and placebo groups, respectively. However, 4 women in the domperidone group failed to complete the study and only the study completers were matched and found to be similar at baseline. No follow-up beyond the 7-day study period was done to evaluate the persistence of an effect of domperidone on lactation success.[43] While this study appears to offer evidence of a beneficial effect on the milk supply in the mothers of preterm infants who are pumping their milk, several factors make this conclusion questionable: a 36% drop-out rate in the active drug group, the lack of an intent-to-treat analysis, and the vast difference in baseline milk supply between the domperidone and placebo groups.

Twenty-five women who had been given domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily to increase milk supply had their dosages decreased over 2 to 4 weeks and discontinued. The duration of domperidone use was not stated in the abstract. All women had stable milk output and were nursing infants under 3 months of age who were growing normally. Of the 25 women, 23 did not increase their use of formula and all infants grew normally, indicating that domperidone can be withdrawn without a detrimental effect on infant nutrition.[57]

Six women who were unable to produce sufficient milk for their preterm infants after counseling by lactation consultants were given domperidone in dosages of 10 mg 3 times daily or 20 mg 3 times daily in a crossover fashion. Baseline serum prolactin concentrations were increased by both dosages to a similar extent. Milk production increased in only 4 of the 6 women. In the other 4 women, milk production increased from 8.7 g/hour at baseline to 23.6 g/hour with 30 mg daily and 29.4 g/hour with 60 mg daily, although there was no statistically significant difference in between the 2 dosages. Side effects in the mothers of dry mouth, abdominal cramping and headache were more frequent with the higher dosage. Severe abdominal cramping caused one mother to drop out of the study during the run-in phase. Additionally, constipation and depressed mood were reported at the higher dosage.[19]

Mothers of preterm infants (<31 weeks) with insufficient milk supply were given either domperidone 10 mg orally 3 times daily or placebo in a randomized, double-blind study. Women who received domperidone had a greater increase in milk volume (+267%) than in the placebo group (19%) at the end of 14 days. Breastmilk calcium concentration increased in the domperidone group (+62%) and decreased (-4%) in the placebo group. Carbohydrate concentrations increased slightly in the mothers receiving domperidone (+2.7%) and decreased slightly (-2.7%) in those receiving placebo. No statistical differences were found in protein, energy, fat, sodium or phosphate concentrations between the groups.[58]

A retrospective, uncontrolled case series reported 14 mothers of preterm infants in the intensive care unit who had been given domperidone 20 mg three times daily to increase their milk supply. The pumped volume of milk increased by 48% over 14 days. However, the lack of a control group renders this report uninterpretable.[59]

Mothers who underwent cesarean section at term were randomized to receive either oral domperidone 10 mg (n = 22) or placebo (n = 23) 4 times daily in a double-blind fashion beginning within the 24 hours postpartum. Nurses collected the mothers' milk with an electric breast pump applied for 15 minutes twice daily 2 hours after the mothers nursed their infants. The volume of milk collected by this incomplete collection technique was greater at all times, including at baseline, in the domperidone group. Seven women in the domperidone group reported dry mouth, and none in the placebo group.[26] Because of the endpoint selected and inequalities at baseline, it is impossible to attribute any clinical relevance to these results.

Mothers who were expressing milk for their infants in a neonatal intensive care unit (mean gestational age 28 weeks) were given instructions on methods for increasing milk supply. If they were producing less than 160 mL of milk per kg of infant weight daily after several days, mothers were randomized to receive either domperidone or metoclopramide 10 mg by mouth 3 times daily for 10 days in a double-blinded fashion. Thirty-one mothers who received domperidone and 34 who received metoclopramide provided data on daily milk volumes during the 10 days. Milk volumes increased over the 10-day period by 96% with domperidone and 94% with metoclopramide, which was not statistically different between the groups. Some mothers continued to measure milk output after the end of the medication period. Results were similar between the 2 groups. Side effects in the domperidone group (3 women) included headache, diarrhea, mood swings and dizziness. Side effects in the metoclopramide group (7 women) included headache (3 women), diarrhea, mood swings, changed appetite, dry mouth and discomfort in the breasts.[27] The lack of a placebo group and the projection of milk volumes to impute missing data from some mothers detract from the findings of this study.

A double-blind, controlled trial compared two dosages of domperidone for increasing milk supply in mothers of preterm infants. Mothers received either 10 mg (n = 8) or 20 mg (n = 7) three times daily for 4 weeks, followed by a tapering dosage over the subsequent 2 weeks. Both dosages increased milk volume, but there was no statistically significant different in milk volumes between the two groups.[20]

A randomized trial in Pakistan compared the effects of domperidone 10 mg to placebo 3 times daily in women who delivered at term and had 10 mL or less of milk production from both breasts per single expression on day 6 postpartum. All women were given some counseling about proper breastfeeding technique. After 7 days of drug or placebo use, women were categorized as having either 50 mL or greater milk production per single expression or less than 50 mL. Serum prolactin was not measured. Seventy-two percent of women given domperidone successfully increased their milk supply compared to 11% in the placebo group. Problems with the study included an apparent lack of blinding of the drugs, investigators and mothers as well as the questionable endpoint of a single expression at an uncontrolled time of day rather than a daily total of milk output.[60]

A retrospective study compared mothers of hospitalized preterm infants who took domperidone (n = 45) to those who did not because of its cost (n = 50). After treatment using a standard protocol, the treated mothers showed an increase in milk supply from 125 mL daily to 415 mL daily after 30 days of treatment. Untreated mothers had a decrease in milk supply from 158 mL daily to 88 mL daily after 30 days.[61,62]

A randomized trial of domperidone (dosage not stated) in India for 7 to 14 days in 32 mothers with insufficient milk production whose infants were in a neonatal ICU found that milk output increased more (186 mL) with domperidone than with placebo (70 mL) after 7 days of therapy. There were no differences in serum prolactin between the domperidone and placebo groups on days 1 and 8 of therapy. There was also no difference in weight gain of the infants between the two groups.[63]

A randomized trial of domperidone 10 mg three times daily in Indonesia for 10 days in 50 mothers with preterm infants and insufficient milk production after 7 days of lactation counseling found that milk output increased more (182 mL) with domperidone than with placebo (72 mL) after 7 days of therapy. The increased milk volume persisted at day 10, three days after drug discontinuation.[64]

A randomized, double-blind study in a hospital in Thailand gave placebo (n = 25) or domperidone 10 mg three time daily (n = 25) for 4 days to mothers who had a normal vaginal delivery of a full-term infant beginning 24 hours postpartum. Milk volumes from a single manual expression were greater at 48 hours postpartum (placebo 3 mL, domperidone 8 mL), 72 hours postpartum (placebo 10 mL, domperidone 15 mL) and 96 hours postpartum (placebo 15 mL, domperidone 35 mL). No follow-up of milk supply or infant outcomes was performed.[65]

In a double-blind, multicenter study, mothers of preterm infants received either domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily for 28 days or placebo three times daily for 14 days followed by domperidone 10 mg 3 times daily for 14 days. Only mothers with documented low milk production were entered into the trial and breastfeeding support was provided to all mothers. Seventy-eight percent of mothers who received domperidone in the first 2 weeks had a 50% increase in milk supply compared to 58% who received placebo (odds ratio 2.56). At the end of 4 weeks, the values were 69% and 62%, but the difference was not statistically significant. At 6 weeks post term gestation, there was no appreciable difference between the groups in the numbers of mothers providing milk to their infants or supplementing with formula. The authors concluded that domperidone supported more mothers to increase their milk volume as early as 8 to 21 days postdelivery; however, the gain in volume was modest.[44] In a secondary analysis of study results, the authors found no difference in response between mothers of infants born between 23 and 26 weeks of gestation and mothers of infants born between 27 and 29 weeks of gestation.[66] Other secondary analyses of the data found no difference in outcome regardless of whether domperidone was started during the period of days 8 to 14 or days 15 to 21 postpartum.[67,68] Mothers with initial volumes of milk of 200 mL/day or less had the greatest percentage of increase in milk volume, but those with initial milk volumes of 100 mL/day or less had continuing low absolute milk volumes.[69]

Women were retrospectively studied following the birth of preterm infants of 30 weeks or less gestational age. Overall, those who received domperidone for lactation enhancement during postpartum hospitalization (n = 84) were no more likely to be nursing their infants at the time of infant discharge from the neonatal unit than mothers who did not receive domperidone (n = 114). However, among mothers weighing 70 kg or more, the use of domperidone was associated with a lower likelihood of breastfeeding on discharge.[70]

A meta-analysis of studies on domperidone use as a galactogogue in the mothers of preterm infants found 5 studies with 95 mothers randomized to domperidone and 97 to placebo. All studies used a dose of 10 mg three times daily for a duration of 5 to 14 days. The results found that domperidone use resulted in an average increase of 88 mL daily with a 95% CI of 57 to 120 mL daily.[3]

A meta-analysis of studies on domperidone use as a galactogogue in mothers who expressed their milk found 5 studies with 120 mothers randomized to domperidone and 125 to placebo. Three of the studies comprising 73 mothers randomized to domperidone and 77 randomized to placebo were included in the previously published meta-analysis ([17]). Four studies used a dose of 10 mg three times daily for a duration of 7 to 14 days, and one used 10 mg four times daily for 4 days. The results found that domperidone use resulted in an average increase of 94 mL daily with a 95% CI of 71 to 117 mL daily. A subanalysis found that using domperidone longer than 7 days provided no additional benefit in increased milk output.[14]

A study of 10 mothers of preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit were administered domperidone 10 mg three times daily if their milk production was either less than 300 mL or 160 mL/kg infant body weight daily after 2 weeks postpartum. The median daily milk volume was 60 mL (range 2–310 mL) initially and 176 mL (range 11–400 mL) on the 14th day. Seven of the 10 mothers had an increase in milk volume to more than 1.5 times their initial volume or greater. The median serum prolactin concentration was 46 mcg/L (range 4–128) before administration and 167 mcg/L (range 59–356) on the 14th day after administration. There was no correlation between serum prolactin and milk production and 3 mothers with elevated prolactin did not produce additional milk.[71]

A randomized study of women (n = 20 in each group) who were mixed feeding their infants in the first month postpartum compared 12 sessions of electroacupuncture or low-level laser therapy to the breast over 1 month and control women. All women also received oral domperidone 10 mg three times daily. Both laser therapy and electroacupuncture increased serum prolactin, infant weight and maternal perception of milk production more than domperidone alone.[72]

A randomized, double-blind trial compared domperidone to placebo in mothers with insufficient milk supply and sick neonates. Of 166 women eligible for the study, 72% of mothers were able to increase their milk production without pharmacological treatment with counseling. Ultimately, 24 women received domperidone 20 mg three times daily for 14 days and 23 received placebo. After 7 days of therapy, the prolactin levels increased from 72.85 mcg/L to 223.4 mcg/L in the domperidone group and from 42.33 mcg/L to 60.08 mcg/L. Milk daily production increased from 156 mL to 401 mL in the domperidone group, and from 176 mL to 261 mL in the placebo group. Ninety-five percent of infants in the domperidone group were breastfeeding at discharge compared to 52% in the placebo group. All differences between groups were statistically significant.[73]

A woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome became a mother through surrogacy. In order to breastfeed her infant, she was treated with a topical estrogen patch, domperidone 20 mg 3 times daily and mechanical breast stimulation starting 4 weeks before delivery. At delivery, the estrogen patch was discontinued. The patient was able to partially breastfeed her infant for 1 month.[5]

In a survey of nursing mothers in Australia, 355 mothers were taking domperidone as a galactogogue. On average, mothers rated domperidone as slightly more than “moderately effective” on a Likert scale. Forty-five percent of mothers taking domperidone reported experiencing adverse reactions, most commonly weight gain, headache, dry mouth and fatigue. Nine percent of women stopped the drug because of side effects.[30,31]

Mothers who had undergone lower-segment cesarean section delivery at or near term and felt that their milk production was inadequate were randomized to receive domperidone 10 mg (n = 183) or placebo (n = 183) three times a day for 3 days. All were shown a 5-minute video on the benefits of breastfeeding. Per protocol analysis found that the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 7 days was greater in the domperidone group compared to placebo (96% vs 86%). Exclusive breastfeeding rates at 3 and 6 months were numerically, but not statistically greater in the domperidone group. Infant weight gain was no different between the groups and 6, 10 and 14 weeks and 9 months postpartum.[74]

A transgender woman was pumping milk and partly breastfeeding her partner’s infant. Pooled 24-hour milk samples were analyzed about monthly beginning at 56 days before delivery. The participant’s milk had values of protein, fat, lactose, and calorie content at or above those of standard term milk.[7]

A transgender woman was taking sublingual estradiol 4 mg twice daily, spironolactone 100 mg twice daily and progesterone 200 mg at bedtime for gender-affirming therapy. In order to prepare for the birth of the infant being carried by her partner, sublingual estradiol was increased to 6 mg twice daily and progesterone was increased to 400 mg at bedtime. Domperidone 10 mg twice daily was also started to increase serum prolactin levels and later increased to 20 mg 4 times daily. Before the delivery date, progesterone was stopped, spironolactone was decreased to 100 mg daily and estradiol was changed to 25 mcg per day transdermally. At day 59 postpartum, estradiol was changed to 2 mg per day sublingually and spironolactone was increased to 100 mg twice daily. The patient was able to produce up to 240 mL of milk daily containing typical macronutrient and oligosaccharide levels.[8]

A randomized study of women who delivered a single infant vaginally compared domperidone 10 mg to the Thai herbal product, Plook-Fire-Thatu and placebo, each given three times daily starting on the first day postpartum. Plook-Fire-Thatu contains several herbs from the genus Piper (pepper) and piperine may be the active ingredient. Piperine also enhances the bioavailability of some chemicals. Ginger, which is a purported galactogogue, is also included in the formula. Milk output was measured by test weighing infants three times daily. On day 3 of treatment, the herbal product resulted in a greater increase in milk production than placebo or domperidone, but there was no difference in infant weights between groups. Maternal temperatures were greater in the herbal group, which is in accord with the Chinese theory of increasing heat to improve lactation.[75]

A transgender woman who wished to breastfeed was given estradiol transdermal patch 150 mcg daily and progesterone 100 mg daily by mouth. Later estradiol spray 100 mcg and domperidone 10 mg 4 times daily were added. Domperidone dosage was then doubled to 20 mg 4 times daily and progesterone was doubled to 100 mg twice daily. After further adjustment of estradiol and progesterone dosages, 7 mL of milk was produced with pumping, but 2 weeks after the infant’s birth, lactation induction was discontinued at the patient’s request.[11]

A 50-year-old transgender woman wished to breastfeed the expected infant of her partner. She was given domperidone in dosages increasing from 30 mg to 800 mg daily along with estradiol and progesterone to stimulate lactation. The patient was able to produce small quantities of milk and was able to directly breastfeed the infant.[10]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

References

- 1.

- Anon. FDA warns against women using unapproved drug, domperidone, to increase milk production. FDA Talk Paper 2004. http://www

.fda.gov/Drugs /DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass /ucm173886.htm. Accessed October 10, 2012 - 2.

- Winterfeld U, Meyer Y, Panchaud A, et al. Management of deficient lactation in Switzerland and Canada: A survey of midwives' current practices. Breastfeed Med 2012;7:317-8. [PubMed: 22224508]

- 3.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Smithers LG, Amir LH, et al. Domperidone for increasing breast milk volume in mothers expressing breast milk for their preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2018;125:1371-8. [PubMed: 29469929]

- 4.

- Reisman T, Goldstein Z. Case report: Induced lactation in a transgender woman. Transgend Health 2018;3:24-6. [PMC free article: PMC5779241] [PubMed: 29372185]

- 5.

- LeCain M, Fraterrigo G, Drake WM. Induced lactation in a mother through surrogacy with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS). J Hum Lact 2020;36:791-4. [PubMed: 31895601]

- 6.

- Glover K, Casey JJ, Gilbert M. Case report: Induced lactation in an adoptive parent. Am Fam Physician 2023;107:119-20. [PubMed: 36791458]

- 7.

- Weimer AK. Lactation induction in a transgender woman: Macronutrient analysis and patient perspectives. J Hum Lact 2023;39:488-94. [PubMed: 37138506]

- 8.

- Delgado D, Stellwagen L, McCune S, et al. Experience of induced lactation in a transgender woman: Analysis of human milk and a suggested protocol. Breastfeed Med 2023;18:888-93. [PubMed: 37910800]

- 9.

- Al-Mohsen ZA, Frookh Jamal H. Induction of lactation after adoption in a muslim mother with history of breast cancer: A case study. J Hum Lact 2021;37:194-9. [PubMed: 33275500]

- 10.

- Ikebukuro S, Tanaka M, Kaneko M, et al. Induced lactation in a transgender woman: Case report. Int Breastfeed J 2024;19:66. [PMC free article: PMC11411746] [PubMed: 39300546]

- 11.

- van Amesfoort JE, Van Mello NM, van Genugten R. Lactation induction in a transgender woman: Case report and recommendations for clinical practice. Int Breastfeed J 2024;19:18. [PMC free article: PMC10926588] [PubMed: 38462609]

- 12.

- Brodribb W. ABM Clinical Protocol #9: Use of galactogogues in initiating or augmenting maternal milk production, second revision 2018. Breastfeed Med 2018;13:307-14. [PubMed: 29902083]

- 13.

- Breastfeeding challenges: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 820. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137:e42-e53. [PubMed: 33481531]

- 14.

- Taylor A, Logan G, Twells L, et al. Human milk expression after domperidone treatment in postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hum Lact 2019;35:501-9. [PubMed: 30481478]

- 15.

- Shen Q, Khan KS, Du MC, et al. Efficacy and safety of domperidone and metoclopramide in breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breastfeed Med 2021;16:516-29. [PubMed: 33769844]

- 16.

- Anderson PO, Valdés V. A critical review of pharmaceutical galactagogues. Breastfeed Med 2007;2:229-42. [PubMed: 18081460]

- 17.

- Paul C, Zenut M, Dorut A, et al. Use of domperidone as a galactagogue drug: A systematic review of the benefit-risk ratio. J Hum Lact 2015;31:57-63. [PubMed: 25475074]

- 18.

- McBride GMcK, Rumbold AR, Keir AK, et al. Longitudinal trends in domperidone dispensing to mothers of very preterm infants and its association with breast milk feeding at infant discharge: A retrospective study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2023;7:e002195. [PMC free article: PMC10626788] [PubMed: 37923344]

- 19.

- Wan EW, Davey K, Page-Sharp M, et al. Dose-effect study of domperidone as a galactagogue in preterm mothers with insufficient milk supply, and its transfer into milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;66:283-9. [PMC free article: PMC2492930] [PubMed: 18507654]

- 20.

- Knoppert DC, Page A, Warren J, et al. The effect of two different domperidone dosages on maternal milk production. J Hum Lact 2013;29:38-44. [PubMed: 22554679]

- 21.

- Health Canada endorsed important safety information on domperidone maleate. [Accessed October 10, 2012]. 2012. http://www

.hc-sc.gc.ca /dhp-mps/medeff/advisories-avis /prof/_2012 /domperidone_hpc-cps-eng.php. - 22.

- Bozzo P, Koren G, Ito S. Health Canada advisory on domperidone: Should I avoid prescribing domperidone to women to increase milk production? Can Fam Physician 2012;58:952-3. [PMC free article: PMC3440266] [PubMed: 22972723]

- 23.

- Smolina K, Mintzes B, Hanley GE, et al. The association between domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia in the postpartum period. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:1210-4. [PubMed: 27296864]

- 24.

- Moriello C, Paterson JM, Reynier P, et al. Off-label postpartum use of domperidone in Canada: A multidatabase cohort study. CMAJ Open 2021;9:E500-E9. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200084 [PMC free article: PMC8157989] [PubMed: 33990364] [CrossRef]

- 25.

- Blusztein D, Peters S, Joshi S. Diagnosis of long QT syndrome triggered by domperidone use for breast-feeding. Heart Lung Circul 2017;26:S163. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2017.06.274 [CrossRef]

- 26.

- Jantarasaengaram S, Sreewapa P. Effects of domperidone on augmentation of lactation following cesarean delivery at full term. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;116:240-3. [PubMed: 22189066]

- 27.

- Ingram J, Taylor H, Churchill C, et al. Metoclopramide or domperidone for increasing maternal breast milk output: A randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F241-5. [PubMed: 22147287]

- 28.

- Sewell CA, Chang CY, Chehab MM, et al. Domperidone for lactation: What health care providers need to know. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:1054-8. [PubMed: 28486375]

- 29.

- Hale TW, Kendall-Tackett K, Cong Z. Domperidone versus metoclopramide: Self-reported side effects in a large sample of breastfeeding mothers who used these medications to increase milk production. Clin Lact (Amarillo) 2018;9:10-7. doi:10.1891/2158-0782.9.1.10 [CrossRef]

- 30.

- McBride GM, Stevenson R, Zizzo G, et al. Use and experiences of galactagogues while breastfeeding among Australian women. PLoS One 2021;16:e0254049. [PMC free article: PMC8248610] [PubMed: 34197558]

- 31.

- McBride GM, Stevenson R, Zizzo G, et al. Women's experiences with using domperidone as a galactagogue to increase breast milk supply: An Australian cross-sectional survey. Int Breastfeed J 2023;18:11. [PMC free article: PMC9903405] [PubMed: 36750944]

- 32.

- Suain Bon R, Mahmud AA. Domperidone use as a galactagogue and infanticide ideation: A case report. Breastfeed Med 2022;17:698-701. [PubMed: 35793516]

- 33.

- Health Canada. Domperidone and psychiatric withdrawal events when used off-label for lactation stimulation. Health Product InfoWatch 2023. https://www

.canada.ca /en/health-canada/services /drugs-health-products /medeffect-canada /health-product-infowatch /august-2023.html#a3-1-1 - 34.

- Papastergiou J, Abdallah M, Tran A, et al. Domperidone withdrawal in a breastfeeding woman. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2013;146:210-2. [PMC free article: PMC3734912] [PubMed: 23940477]

- 35.

- Seeman MV. Transient psychosis in women on clomiphene, bromocriptine, domperidone and related endocrine drugs. Gynecol Endocrinol 2015;31:751-4. [PubMed: 26291819]

- 36.

- Doyle M, Grossman M. Case report: Domperidone use as a galactagogue resulting in withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation. Arch Womens Ment Health 2018;21:461-3. [PubMed: 29090362]

- 37.

- Manzouri P, Mink M. Withdrawal effects from domperidone requiring prolonged tapering schedule. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:e112. doi:10.1002/phar.2028 [CrossRef]

- 38.

- Sharma V, Sharma S, Doobay M. Domperidone withdrawal in a nursing female with pre-existing psychiatric illness: Case report. Curr Drug Saf 2022;17:278-80. [PubMed: 34645378]

- 39.

- Majdinasab E, Haque S, Stark A, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of withdrawal following domperidone used as a galactagogue. Breastfeed Med 2022;17:1018-24. [PubMed: 36367713]

- 40.

- Krutsch K, Datta P. The transfer of domperidone into human milk remains low at high doses. Breastfeed Med 2023;18:555-6. [PubMed: 37352416]

- 41.

- De Leo V, Petraglia F, Sardelli S, et al. Use of domperidone in the induction and maintenance of maternal breast feeding. Minerva Ginecol 1986;38:311-5. [PubMed: 3725173]

- 42.

- Petraglia F, De Leo V, Sardelli S, et al. Domperidone in defective and insufficient lactation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1985;19:281-7. [PubMed: 3894101]

- 43.

- da Silva OP, Knoppert DC, Angelini MM, et al. Effect of domperidone on milk production in mothers of premature newborns: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CMAJ 2001;164:17-21. [PMC free article: PMC80627] [PubMed: 11202662]

- 44.

- Asztalos EV, Campbell-Yeo M, da Silva OP, et al. Enhancing human milk production with domperidone in mothers of preterm infants. J Hum Lact 2017;33:181-7. [PubMed: 28107101]

- 45.

- Wamboldt R, Shuster S, Sidhu BS. Lactation induction in a transgender woman wanting to breastfeed: Case report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:e2047-e52. [PubMed: 33513241]

- 46.

- Brouwers JR, Assies J, Wiersinga WM, et al. Plasma prolactin levels after acute and subchronic oral administration of domperidone and of metoclopramide: A cross-over study in healthy volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1980;12:435-40. [PubMed: 7428183]

- 47.

- Hofmeyr GJ, van Iddekinge B, Blott JA. Domperidone: Secretion in breast milk and effect on puerperal prolactin levels. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92:141-4. [PubMed: 3882143]

- 48.

- Brown TE, Fernándes PA, Grant LJ, et al. Effect of parity on pituitary prolactin response to metoclopramide and domperidone: Implications for the enhancement of lactation. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2000;7:65-9. [PubMed: 10732318]

- 49.

- Poovathingal MA, Bhat R, Ramamoorthi. Domperidone induced galactorrhea: An unusual presentation of a common drug. Indian J Pharmacol 2013;45:307-8. [PMC free article: PMC3696311] [PubMed: 23833383]

- 50.

- Jabbar A, Khan R, Farrukh SN. Hyperprolactinaemia induced by proton pump inhibitor. J Pak Med Assoc 2010;60:689-90. [PubMed: 20726208]

- 51.

- Nijhawan S, Rai RR, Sharma CM. Domperidone induced galactorrhea. Indian J Gastroenterol 1991;10:113. [PubMed: 1916962]

- 52.

- Demir AM, Kuloglu Z, Berberoglu M, et al. Euprolactinemic galactorrhea secondary to domperidone treatment. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2015;28:955-6. [PubMed: 25781524]

- 53.

- De S, Taylor CM. Domperidone toxicity in an infant on maintenance haemodialysis. Pediatr Nephrol 2007;22:161-2. [PubMed: 16960712]

- 54.

- Yedla D, Sharmila V. Atypical presentation of domperidone-induced galactorrhea. Indian J Pharmacol 2022;54 381-2. [PMC free article: PMC9846906] [PubMed: 36537410]

- 55.

- Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD. Galactorrhoea as side effect of domperidone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1395-6. [PMC free article: PMC1547854] [PubMed: 6404476]

- 56.

- Prasad A, Agrawal S, Pradhan C, et al. Domperidone induced galactorrhoea in reproductive age group females-a case series. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2024;31:343-6. doi:10.53555/jptcp.v31i4.5458 [CrossRef]

- 57.

- Livingstone V, Blaga Stancheva, L, Stringer J. The effect of withdrawing domperidone on formula supplementation. Breastfeed Med 2007;2:178. doi:10.1089/bfm.2007.9985 [CrossRef]

- 58.

- Campbell-Yeo ML, Allen AC, Joseph KS, et al. Effect of domperidone on the composition of preterm human breast milk. Pediatrics 2010;125:e107-14. [PubMed: 20008425]

- 59.

- Wagner CL, Murphy PK, Haase B, et al. Domperidone in the treatment of low milk supply in mothers of critically ill neonates. Breastfeed Med 2011;6 (Suppl 1):S-21. doi:10.1089/bfm.2011.9985 [CrossRef]

- 60.

- Inam I, Navinés AB, Shahid A. A comparison of efficacy of domperidone and placebo among postnatal women with inadequate breast milk production. Pak J Med Health Sci 2013;7:314-6. https://pjmhsonline

.com/2013/apr_june/ - 61.

- Haase B, Taylor S, Morella K, et al. Domperidone for treatment of low milk supply in mothers of hospitalized premature infants: A multidisciplinary development of safe prescribing guidelines and a retrospective chart review (2010-2014) of maternal response to treatment. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:A22. doi:10.1089/bfm.2016.28999.abstracts [CrossRef]

- 62.

- Haase B, Taylor SN, Mauldin J, et al. Domperidone for treatment of low milk supply in breast pump-dependent mothers of hospitalized premature infants: A clinical protocol. J Hum Lact 2016;32:373-81. [PubMed: 26905341]

- 63.

- Rai R, Mishra N, Singh DK. Effect of domperidone in 2nd week postpartum on milk output in mothers of preterm infants. Indian J Pediatr 2016;83:894-5. [PubMed: 27109392]

- 64.

- Fazilla TE, Tjipta GD, Ali M, et al. Domperidone and maternal milk volume in mothers of premature newborns. Paediatr Indones 2017;57:18-22. doi:10.14238/pi57.1.2017.17-22 [CrossRef]

- 65.

- Wannapat M, Suthutvoravut S, Suwikrom S. Effectiveness of domperidone in augmenting breastmilk production measured by manual expression in postpartum women in Charoenkrung Pracharak Hospital. Ramathibodi Medical Journal 2018;41:17-26. https://he02

.tci-thaijo .org/index.php/ramajournal /article/view/85234 - 66.

- Asztalos EV, Kiss A, da Silva OP, et al. Pregnancy gestation at delivery and breast milk production: A secondary analysis from the EMPOWER trial. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 2018;4:21. [PMC free article: PMC6217780] [PubMed: 30410781]

- 67.

- Asztalos EV, Kiss A, da Silva OP, et al. Evaluating the effect of a 14-day course of domperidone on breast milk production: A per-protocol analysis from the EMPOWER trial. Breastfeed Med 2019;14:102-7. [PubMed: 30543461]

- 68.

- Asztalos EV, Kiss A, da Silva OP, et al. Role of days postdelivery on breast milk production: A secondary analysis from the Empower trial. Int Breastfeed J 2019;14:21. [PMC free article: PMC6547502] [PubMed: 31171928]

- 69.

- Asztalos EV, Kiss A. Early breast milk volumes and response to galactogogue treatment. Children (Basel) 2022;9:1042. [PMC free article: PMC9315761] [PubMed: 35884026]

- 70.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Amir LH, Smithers LG. Longer-term breastfeeding outcomes associated with domperidone use for lactation differs according to maternal weight. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2018;74:1071-5. [PubMed: 29725699]

- 71.

- Wada Y, Suyama F, Sasaki A, et al. Effects of domperidone in increasing milk production in mothers with insufficient lactation for infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Breastfeed Med 2019;14:744-7. [PubMed: 31483145]

- 72.

- Maged AM, Hassanin ME, Kamal WM, et al. Effect of low-level laser therapy versus electroacupuncture on postnatal scanty milk secretion: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol 2020;37:1243-9. [PubMed: 31327162]

- 73.

- Khorana M, Wongsin P, Torbunsupachai R, et al. Effect of domperidone on breast milk production in mothers of sick neonates: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Breastfeed Med 2021;16:245-50. [PubMed: 33202169]

- 74.

- Archana A, Adhisivam B, Chaturvedula L, et al. Oral domperidone versus placebo for enhancing exclusive breastfeeding among post-lower segment cesarean section mothers - a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2023;36:2185754. [PubMed: 36863712]

- 75.

- Krungkraipetch K, Kwanchainon C. The use of Thai herbal galactogogue, 'Plook-Fire-Thatu', for postpartum heat re-balancing. Afr J Reprod Health 2023;27:85-98. [PubMed: 37742337]

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Domperidone

CAS Registry Number

57808-66-9

Drug Class

Breast Feeding

Lactation

Milk, Human

Antiemetics

Dopamine Antagonists

Galactogogues

Gastrointestinal Agents

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

Publication Details

Publication History

Last Revision: October 15, 2024.

Copyright

Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Publisher

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda (MD)

NLM Citation

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Domperidone. [Updated 2024 Oct 15].