CASRN: 537-46-2

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Because there is no published experience with methamphetamine as a therapeutic agent during breastfeeding, an alternate drug may be preferred, especially while nursing a newborn or preterm infant. One expert recommends that amphetamines not be used therapeutically in nursing mothers.[1]

Methamphetamine should not be used as a recreational drug by nursing mothers because it may impair their judgment and childcare abilities. Methamphetamine and its metabolite, amphetamine, are detectable in breastmilk and infant's serum after abuse of methamphetamine by nursing mothers. However, these data are from random collections rather than controlled studies because of ethical considerations in administering recreational methamphetamine to nursing mothers. Other factors to consider are the possibility of positive urine tests in breastfed infants which might have legal implications, and the possibility of other harmful contaminants in street drugs. Breastfeeding is generally discouraged in mothers who are actively abusing amphetamines.[2-5] In mothers who abuse methamphetamine while nursing, withholding breastfeeding for 48 to 100 hours after the maternal use been recommended, although in many mothers methamphetamine is undetectable in breastmilk after an average of 72 hours from the last use.[6,7] It has been suggested that breastfeeding can be reinstated 24 hours after a negative maternal urine screen for amphetamines.[7]

Drug Levels

Methamphetamine is metabolized to several metabolites, including the active metabolite, amphetamine.

Maternal Levels. Two nursing mothers who were intravenous methamphetamine abusers collected milk samples just before methamphetamine injection and every 2 to 6 hours after injection for 24 hours. Because the drugs were illicit street drugs, the doses of methamphetamine were not known. Peak and average milk methamphetamine concentrations were about 160 mcg/L and 111 mcg/L in one woman and 610 mcg/L and 281 mcg/L in the other, respectively. Milk methamphetamine concentrations fell with half-lives of 13.6 and 7.4 hours, respectively. Amphetamine, thought to be derived from metabolism of methamphetamine, was present in relatively constant concentrations in the milk of both mothers, averaging 4 and 15 mcg/L, respectively. The authors estimated that the infants would have received daily dosages of 16.7 and 42.2 mcg/kg of methamphetamine and 0.8 and 2.5 mcg/kg of amphetamine, respectively.[6] These estimated mg/kg infant doses of methamphetamine are lower than therapeutic doses of the equipotent dextroamphetamine for older children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. However, this is not evidence of safety for breastfed infants because the data on these two women cannot be extrapolated to other methamphetamine abusers.

Thirty-three mothers in Thailand were identified who had predelivery urine drug screens positive for methamphetamine. On average they used methamphetamine 2.4 times per week, primarily by smoking crushed tablets. Of these, 22 had undetectable postpartum methamphetamine milk levels. Of the 11 mothers with methamphetamine in breastmilk, only two mothers had more than 1 consecutive milk samples containing methamphetamine that were analyzed. The mothers had smoked methamphetamine (dosage uncertain) 53 and 68 hours prior to delivery, respectively. First milk samples contained 142 and 345 mcg/L of methamphetamine in the two mothers. The half-lives of methamphetamine in breastmilk were 11.3 and 40.3 hours, respectively. The authors estimated that in the first 24 hours after birth their exclusively breastfed infant would have received daily dosages of 59.3 mcg or 21.3 mcg/kg in the first case and 93.0 mcg or 51.7 mcg/kg in the second case, although the authors used an unrealistically high milk intake for a 1-day-old infant to estimate the dose. Methamphetamine became undetectable in breastmilk about 100 hours after the last drug use in both mothers, which was about one day prior to the mothers' urine becoming negative for methamphetamine.[7]

Milk from 2 mothers suspected of methamphetamine abuse were analyzed by 5 different methods. In one sample, the average methamphetamine concentration was 327 mcg/L (range 294 to 347 mcg/L) and the average amphetamine concentration was 79.9 mcg/L (range 74.9 to 88.4 mcg/L). In the second sample, the average methamphetamine concentration from 3 of the methods was 3.8 mcg/L (range 3.4 to 4.1 mcg/L) and the average amphetamine concentration from 2 of the methods was 1 mcg/L. The other methods did not detect the drugs.[8]

Infant Levels. Relevant published information was not found as of the revision date.

Effects in Breastfed Infants

A 2-month-old infant whose mother used illicit street methamphetamine recreationally by nasal inhalation was found dead 8 hours after a small amount of breastfeeding and ingestion of 120 to 180 mL of formula. The infant's serum methamphetamine concentration on autopsy was 39 mcg/L. Although the infant's mother was convicted of child endangerment for the use of methamphetamine during breastfeeding, the role that methamphetamine played in the infant's death has been questioned because of the low infant serum methamphetamine concentration and the mother's alleged minimal breastfeeding.[9,10]

South Australian government pathologists reported the death of a breastfed infant who was co-sleeping with its mother. Methamphetamine was found in a “significant” concentration in the infant on autopsy and the drug in breastmilk was thought to be potentially contributory to the death. These authors also reported that in prior deaths of infants under 12 months of age, detectable methamphetamine and its metabolite, amphetamine, may have been partially obtained via breastmilk.[11] Pathologists from the New Zealand government confirmed similar findings in their country.[12]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

A single oral dose of 0.2 mg/kg to a maximum of 17.5 mg of d-methamphetamine was given to 6 subjects (4 male and 2 female). Serum prolactin concentrations were unchanged over a period of 300 minutes after the dose.[13]

In 2 papers by the same authors, 20 women with normal physiologic hyperprolactinemia were studied on days 2 or 3 postpartum. Eight received dextroamphetamine 7.5 mg intravenously, 6 received 15 mg intravenously and 6 who served as controls received intravenous saline. The 7.5 mg dose reduced serum prolactin by 25 to 32% compared to control, but the difference was not statistically significant. The 15 mg dose significantly decreased serum prolactin by 30 to 37% at times after the infusion. No assessment of milk production was presented. The authors also quoted data from another study showing that a 20 mg oral dose of dextroamphetamine produced a sustained suppression of serum prolactin by 40% in postpartum women.[14,15]

A study compared 31 methamphetamine-dependent subject to 23 non-dependent subjects. The serum prolactin concentrations in the methamphetamine-dependent subjects were elevated at days 2 and 30 of abstinence. The elevation was greater in women than in men.[16] The maternal prolactin level in a mother with established lactation may not affect her ability to breastfeed.

In a retrospective Australian study, mothers who used intravenous amphetamines during pregnancy were less likely to be breastfeeding their newborn infants at discharge than mothers who abused other drugs (27% vs 42%). The cause of this difference was not determined.[17]

A prospective, multicenter study followed mothers who used methamphetamine prenatally (n = 204) to those who did not (n = 208). Infants exposed to methamphetamine exhibited poor suck, excessive suck and more jitteriness compared to nonexposed infants. Mothers who used methamphetamine were less likely to breastfeed their infants (38%) at hospital discharge than those who did not use methamphetamine (76%).[18]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

(ADHD) Amphetamine, Dextroamphetamine, Lisdexamfetamine, Methylphenidate

References

- 1.

- Ornoy A. Pharmacological treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during pregnancy and lactation. Pharm Res 2018;35:46. [PubMed: 29411149]

- 2.

- ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion No. 479: Methamphetamine abuse in women of reproductive age. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:751-5. [PubMed: 21343793]

- 3.

- Oei JL, Kingsbury A, Dhawan A, et al. Amphetamines, the pregnant woman and her children: A review. J Perinatol 2012;32:737-47. [PubMed: 22652562]

- 4.

- AAP Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129:e827-41. [PubMed: 22371471]

- 5.

- Wong S, Ordean A, Kahan M. SOGC clinical practice guidelines: Substance use in pregnancy: No. 256, April 2011. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;114:190-202. [PubMed: 21870360]

- 6.

- Bartu A, Dusci LJ, Ilett KF. Transfer of methylamphetamine and amphetamine into breast milk following recreational use of methylamphetamine. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:455-9. [PMC free article: PMC2679109] [PubMed: 19371319]

- 7.

- Chomchai C, Chomchai S, Kitsommart R. Transfer of methamphetamine (MA) into breast milk and urine of postpartum women who smoked MA tablets during pregnancy: Implications for initiation of breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 2016;32:333-9. [PubMed: 26452730]

- 8.

- Bavlovič Piskáčková H, Nemeškalová A, Kučera R, et al. Advanced microextraction techniques for the analysis of amphetamines in human breast milk and their comparison with conventional methods. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022;210:114549. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114549 [PubMed: 34998075] [CrossRef]

- 9.

- Ariagno R, Karch SB, Middleberg R, et al. Methamphetamine ingestion by a breast-feeding mother and her infant's death: People v Henderson. JAMA 1995;274:215. [PubMed: 7609223]

- 10.

- Green LS. People v Henderson: The prosecution responds. JAMA 1996;275:183-4. [PubMed: 8604164]

- 11.

- Kenneally M, Byard RW. Increasing methamphetamine detection in cases of early childhood fatalities. J Forensic Sci 2020;65:1376-8. [PubMed: 32202648]

- 12.

- Tse R, Kesha K, Morrow P, et al. Commentary on: Kenneally M, Byard RW. Increasing methamphetamine detection in cases of early childhood fatalities. J Forensic Sci 2020;65:1384. [PubMed: 32510633]

- 13.

- Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Thelen B, Habermeyer E, et al. Psychopathological, neuroendocrine and autonomic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDE), psilocybin and d-methamphetamine in healthy volunteers. Results of an experimental double-blind placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:41-50. [PubMed: 10102781]

- 14.

- DeLeo V, Cella SG, Camanni F, et al. Prolactin lowering effect of amphetamine in normoprolactinemic subjects and in physiological and pathological hyperprolactinemia. Horm Metab Res 1983;15:439-43. [PubMed: 6642414]

- 15.

- Petraglia F, De Leo V, Sardelli S, et al. Prolactin changes after administration of agonist and antagonist dopaminergic drugs in puerperal women. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1987;23:103-9. [PubMed: 3583091]

- 16.

- Zorick T, Mandelkern MA, Lee B, et al. Elevated plasma prolactin in abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2011;37:62-7. [PMC free article: PMC3056536] [PubMed: 21142706]

- 17.

- Oei J, Abdel-Latif ME, Clark R, et al. Short-term outcomes of mothers and infants exposed to antenatal amphetamines. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2010;95:F36-F41. [PubMed: 19679891]

- 18.

- Shah R, Díaz SD, Arria A, et al. Prenatal methamphetamine exposure and short-term maternal and infant medical outcomes. Am J Perinatol 2012;29:391-400. [PMC free article: PMC3717348] [PubMed: 22399214]

Substance Identification

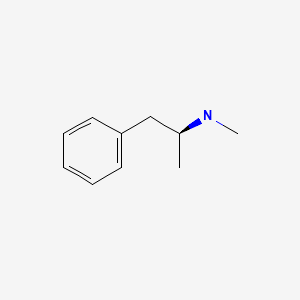

Substance Name

Methamphetamine

CAS Registry Number

537-46-2

Drug Class

Breast Feeding

Lactation

Milk, Human

Street Drugs

Sympathomimetics

Dopamine Agents

Central Nervous System Stimulants

Adrenergic Agents

Wakefulness-Promoting Agents

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

Publication Details

Publication History

Last Revision: September 15, 2024.

Copyright

Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Publisher

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda (MD)

NLM Citation

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Methamphetamine. [Updated 2024 Sep 15].