NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details19. Early versus late consultant review

19.1. Introduction

Traditional models of medicine have often relied on patients being admitted by one of the more junior members of the medical team, then reviewed by a middle grade member, and only reviewed by a consultant several hours later on the ‘post take’ round, which may be the following day or even later in the week. This model has the potential to cause delays in timely investigation, diagnosis, and treatment, or in errors in care, which may translate into delayed discharge from hospital or patient harm. In the last decade several professional organisations have developed pragmatic recommendations for earlier and more frequent consultant review.

Earlier consultant review may allow the less sick patient to go home earlier, possibly even avoiding admission and also allowing earlier recognition of the sicker patient, with earlier institution of effective therapy and possibly decreased mortality. However, earlier discharge may lead to more re-admissions, and earlier reviews may not be effective if relevant tests results are not available. Equally, different age groups and different illnesses may have different results. However, it would seem reasonable that early review by a senior and more experienced doctor should improve the patient’s experience of healthcare.

The guideline committee therefore wanted to know if there was a net patient benefit to having a consultant review patients early in their presentation to hospital, what this might be and whether there was a difference depending on how sick the patient was and what was wrong with them. This would need to be balanced against any potential harm that might occur and how much it might cost.

19.2. Review questions

Is early consultant triage in the ED (Rapid Assessment and Treatment (RAT) model) more clinically and cost effective than later consultant review?

Is early consultant review in the AMU, ICU, HDU, CCU or Stroke Unit more clinically and cost effective than later consultant review?

For full details see review protocols in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

19.3. Clinical evidence

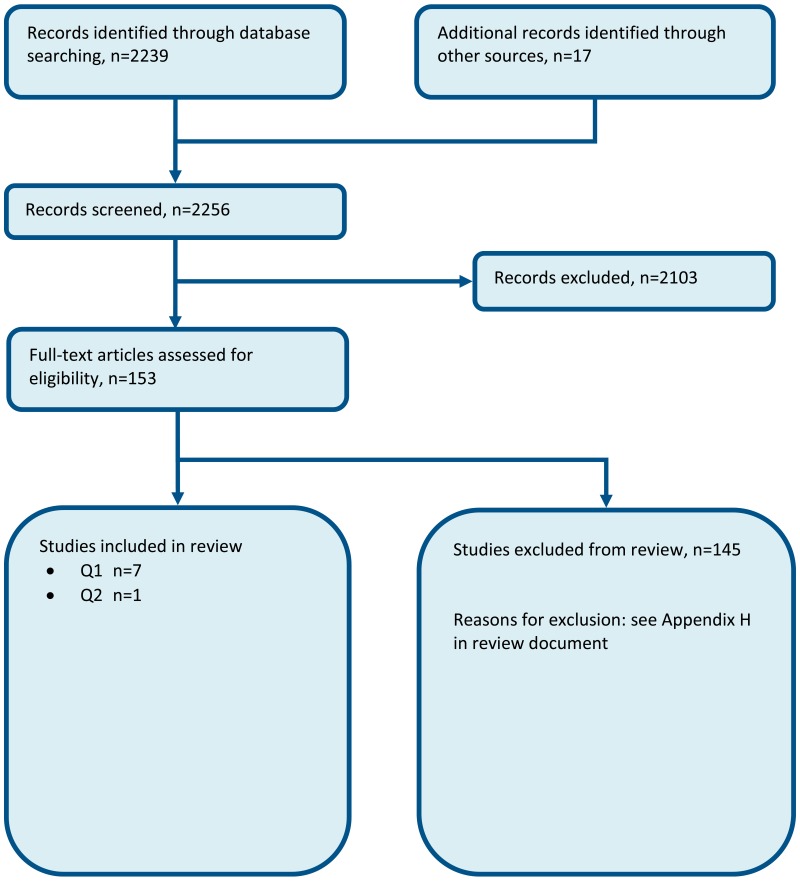

Eight studies were included in the review12,32,41,67,77,110,132,151 and are summarised below. Evidence from these studies are summarised in the GRADE clinical evidence profile and clinical evidence summary below (Table 3, Table 4, Table 7). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 3

Clinical evidence summary: Early versus late consultant review in ED: RCT evidence (SWAT versus control).

Table 4

Clinical evidence summary: Early versus late consultant review in ED: observational evidence.

Table 7

Clinical evidence summary: Early versus late consultant review in AMU (Consultant absent versus Consultant present): Cohort study evidence.

We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the effect of early versus late consultant triage in 5 different settings (ED, ICU, AMU, CCU and stroke units) on patient outcomes.

One RCT41 was included which was set in the ED and compared the effects of a model of care aiming to implement early senior work up assessment and treatment with no model of care.

Six observational studies12,32,67,77,132,151 were included in the ED. Three of these studies12,77,132 were similar in design to the RCT in that an intervention was implemented to facilitate early consultant review, which was then compared to days on which the intervention was not implemented; however, patients were not randomised to treatment. Two of these studies77,132 were confounded by the addition of point of care testing to the intervention of early consultant review and were downgraded for risk of bias. One of these studies was confounded by the intervention being carried out on days of peak demand;12 however this study did adjust for confounding variables.

Two of the 6 observational studies set in ED presented data from naturally occurring situations in which some patients were seen exclusively by consultants due to the absence or reduced availability of junior doctors.32,67 Outcomes were compared with times when junior doctors were present. One of these studies67 was confounded by different triage scores at baseline between the 2 groups and was therefore downgraded for risk of bias.

The final observational study151 set in ED reported the proposed management of patients by junior trainees versus the subsequent effect of the senior review process on patient disposition.

No RCTs set in ICU, AMU, CCU and stroke units were found. One cohort study set in AMU110 was identified.

As no studies reported patient and/or carer satisfaction, data relating to ‘did not wait to be seen’ patients were analysed as a surrogate marker, but downgraded for indirectness to the protocol.

Table 2

Summary of included studies.

Other outcomes that were unable to be analysed in Revman included: length of stay (for all patients): median 261 minutes (IQR 171, 386) in the SWAT group and median 255 minutes (IQR 177,376) in the control (standard care) group. For discharged patients length of stay was median 206 minutes (IQR 140, 294) in the SWAT group and 208 (IQR 147, 283) in control. For admitted patients length of stay was median 374 minutes (IQR 273-494) in the SWAT group and 381 minutes (IQR 274, 478) in control.

19.3.1. Other outcomes that could not be analysed in Revman

Table 5

Clinical evidence summary: Early versus late consultant review in ED: observational evidence.

19.3.2. Clinical investigations

One study67 reported the number of clinical investigations per patient.

Table 6

Clinical evidence summary: Early versus late consultant review in ED: observational evidence.

19.3.3. Unplanned readmissions

One study32 reported that 7.9% (6.5-9.3%) of patients who had been seen during the consultant shift returned to ED within 7 days versus 8.1% (7.4-8.9%) of those seen during the middle grade doctor shift. This paper did not give the number for each group so this data could not be analysed in Revman.

19.3.4. Admissions

One study32 reported that 27.1% (24.2-30.1%) of patients who had been seen during the consultant shift were admitted versus 31.0% (29.6-32.5%) of those seen during the middle grade doctor shift. This paper did not give the number for each group so this data could not be analysed in Revman.

19.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B

New cost-effectiveness analysis

An original cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted for this topic – see the economic profile table below (Table 8) and Chapter 41 for details.

Table 8

Economic evidence profile: Earlier versus later consultant assessment.

19.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

Emergency departments

Seven papers were identified that assessed early versus late consultant reviews in the emergency department. Six of these studies were observation studies and 1 study was a randomised controlled trial.

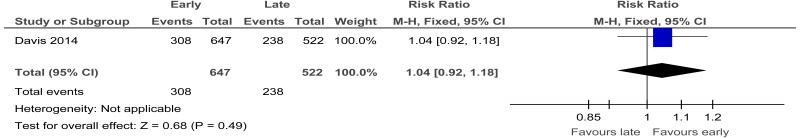

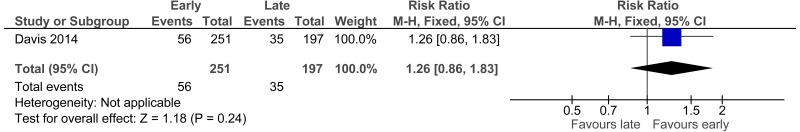

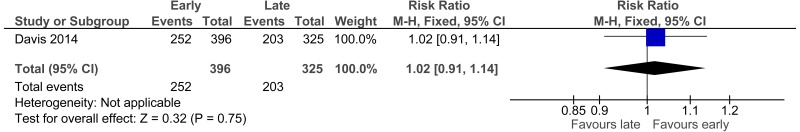

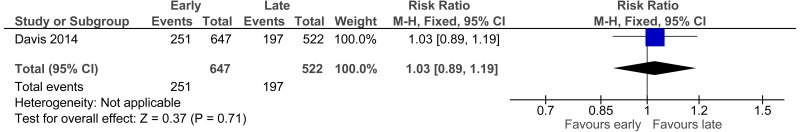

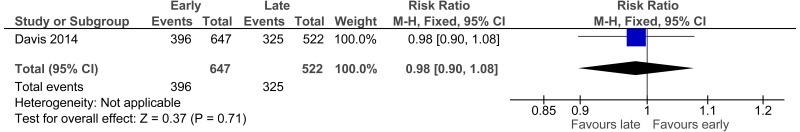

One randomised controlled trial comprising 1737 participants evaluated senior work up assessment treatment (SWAT) with non-SWAT treatment and standard care for improving outcomes, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that SWAT may provide a benefit in increased proportion of patients achieving the National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) (1 study, moderate quality), proportion of admitted patients who met NEAT (1 study, low quality), and proportion of discharged patients who met NEAT (1 study, moderate quality). However, there were more patients admitted (1 study, moderate quality) and fewer patients discharged with early consultant review (1 study, moderate quality).

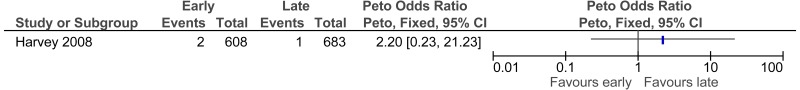

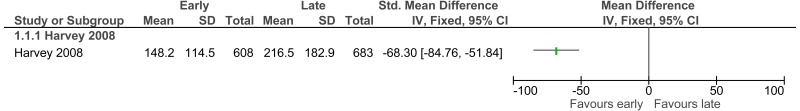

Six observational studies evaluated early versus late consultant reviews for improving outcomes, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that early consultant reviews may provide a benefit in reduced length of ED stay, 30 day unscheduled re-admissions, admissions, patients achieving NEAT, discharged patients achieving NEAT, admitted patients achieving NEAT, patients seen within the recommended time and patients who did not wait to be seen (1 study, very low quality). However, there was a possible increase in mortality (1 study, very low quality).

Acute medical units

One observational study comprising 2928 participants evaluated consultant presence versus when the consultant was absent for improving outcomes, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that consultant reviews may provide a benefit in reduced length of stay and proportion of patients discharged on the same day. There was no effect on mortality during admission. However, there was a possible increase in the proportion of patients discharged within 24 hours and readmitted within 1 week for the same clinical problem. The evidence was graded very low quality for all outcomes.

Economic

An original cost-utility analysis found that Rapid Assessment and Treatment in the Emergency Department (RAT) was not cost-effective (increased costs with no quality-adjusted life-years gained). This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

An original cost-utility analysis (simulation model) found that Rapid Assessment and Treatment in the Emergency Department (RAT) dominated compared to usual care. This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

An original cost-utility analysis found that extended consultant hours on the Acute Medical Unit were not cost-effective (ICER: £39,200 per QALY). This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with minor limitations. This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

19.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendation | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Mortality, quality of life, avoidable adverse events and patient and/or carer satisfaction were considered by the committee to be critical outcomes. Early diagnosis, hospital admission, number of diagnostic tests, length of stay, GP visits, referrals from admission, unplanned readmission, discharge and staff satisfaction were considered to be important outcomes. The committee considered that avoiding readmission was likely to be particularly important for people who have a chronic condition as this has an impact on mortality and also could have an impact upon psychological wellbeing and the ability to maintain independence. |

| Trade-off between clinical benefits and harms |

Emergency Department A single RCT was identified. The committee decided that the Senior Work up Assessment and Treatment (SWAT) intervention had most similarities to current systems in the NHS (Rapid Assessment and Treatment [RAT]) compared to the non-SWAT intervention because for consultants to work effectively, they need the support of a team and therefore seeing patients alone would not be productive. Indeed, in the UK, consultants do not normally see patients in isolation. The comparison of SWAT versus control data suggested that SWAT may provide a benefit in increased proportion of patients achieving the National Emergency Access Target (NEAT), which is to be seen and discharged from the ED within 240 minutes of triage; proportion of admitted patients who met NEAT; and proportion of discharged patients who met NEAT. However, there were more patients admitted and fewer discharged with early consultant review. The committee surmised that early consultant review might, in some circumstances, be disadvantageous if it took place before definitive investigations were available which might have permitted safe discharge on later review. Therefore, review prior to all the relevant information being present may result in a greater number of patients admitted. However, the fact that more patients were admitted, although increasing demand, may be a positive step as it may ensure that certain patients receive the inpatient care their condition requires. The presence of a senior decision maker may identify these patients. The committee discussed their experience of the Rapid Assessment and Treatment system (the UK system of immediate consultant triage at presentation to ED). Perceived benefits included more rapid diagnosis, earlier administration of antibiotics and analgesics, and more appropriate triage. However, such outcomes are not normally measured in trials whereas admission, discharge and length of stay are affected by a wide variety of factors, and therefore may not accurately capture the whole effects of early consultant triage. Six observational studies suggested that early consultant review may provide a benefit in reduced length of ED stay, 30 day unscheduled re-admissions, admissions, patients achieving NEAT, discharged patients achieving NEAT, admitted patients achieving NEAT, patients seen within the recommended time and patients who did not wait to be seen. There was a possible increase in mortality but this was discounted by the committee as there was only a difference of 1 case between the 2 groups. No evidence was identified for early diagnosis, quality of life, GP visits, avoidable adverse events, diagnostic test number, patient and/or carer satisfaction, referral from admissions and staff or trainee satisfaction. Acute Medical Unit A single observational study was identified suggesting that early consultant review may provide a benefit in reduced length of stay, and the proportion of patients discharged on the day of admission. There was no effect on mortality during admission; there was a possible increase in the proportion of patients discharged within 24 hours and readmitted within 1 week for the same clinical problem. No evidence was identified for hospital admission, readmission, early diagnosis, quality of life, GP visits, avoidable adverse events, diagnostic test number, patient and/or carer satisfaction, referral from admissions and staff or trainee satisfaction. Stroke patients: No evidence was identified in a stroke care setting. The committee felt that the results from ED and AMU could be extrapolated to stroke patients. Intensive (or critical) care unit: No evidence was identified in an intensive care unit (critical care unit) setting. Studies of resident versus non-resident intensive care specialists were considered too indirect to be employed as substitutes for early consultant review. Given this lack of evidence, the committee considered that studies in ED and AMU patients might be used to inform recommendations relating to the ICU. Overall The committee noted that the effect of early consultant involvement is dependent upon the staffing model, the presenting case mix and the disease process. For example, conditions with a well-defined treatment pathway may benefit more from early consultant involvement if this results in earlier diagnosis and entry to the pathway. In settings where patients are presenting with often unclear disease processes (for example, in an emergency department), the benefit of early consultant involvement might be realised if consultants’ greater knowledge results in earlier diagnosis, or diminished if the diagnostic process is complex. The committee noted that a range of models for early consultant involvement were used in the studies examined, and that the model used within a UK context may differ from those included in the studies. For example, the Rapid Assessment and Treatment model implemented within some emergency department settings in the UK was a model containing a range of interventions, including early consultant involvement. It was felt to be similar but not identical to the SWAT model in the RCT for EDs. Overall, the evidence was mixed but suggested some benefit in outcomes over usual care for the ED and AMU. No evidence was identified to suggest harm in early consultant involvement and the committee were not aware of any negative outcomes that might occur. They therefore chose to make a consensus recommendation to consider early consultant involvement in care of a patient with an acute medical emergency. However, there was insufficient evidence to recommend specific models such at RAT. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

No relevant economic evaluations were identified. Unit costs of staff time, emergency department visits and relevant hospital admissions and stays were presented to the committee. One RCT, described above, set in the emergency department showed that the SWAT arm of the trial was associated with a trend for more patients meeting the 4-hour target; however, there was also a trend for more admissions and less discharges compared to the control arm. The committee felt that without information on the appropriateness of the decisions to admit or discharge, it would be difficult to fully assess the impact of the SWAT model. Anecdotally, the committee felt that the equivalent model in the UK (Rapid Assessment and Treatment or RAT) had shown some clinical benefit in terms of timely diagnosis and treatment. These benefits might be expected to result in saving in downstream costs. For the AMU, the observational study included in the clinical review suggested that there was a reduction in length of stay, which would translate into possible cost saving. The committee noted that the economic impact of early consultant assessment would be dependent on how it could be achieved or implemented in practice. Possible scenarios discussed included increasing the number of consultants, increasing their contracted hours (which might include working out-of-hours or being on-call) or accommodating the required changes in the consultants’ current rotas by prioritising early patient assessments over other duties, which can be undertaken by other staff members. The committee commented that the most likely scenario in large hospitals is that consultant rotas could be tailored to accommodate prioritising assessing patients given current capacity levels and the limited number of NHS consultants, which precludes the possibility of recruiting more consultants. However, this may not be feasible in smaller hospitals. New cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted for 2 areas of early consultant assessment with the results presented to the committee. A cohort model and a simulation model were built to assess the cost-effectiveness of early consultant assessment. Both models used inputs from bespoke data analysis, national data and treatment effects (primarily length of stay reduction and modest reductions in adverse events) that were informed by the above review but elicited from the committee members. The full model write up can be found in Chapter 41. Rapid Assessment and Treatment in the Emergency Department (RAT) The models compared RAT in the ED with no RAT. RAT involves an immediate assessment by a consultant in the ED, using additional resources in terms of consultant time at an incremental cost to normal care. Both models found that RAT was cost increasing with assumed no impact on quality of life, hence no gain in quality-adjusted life-years. The committee noted that RAT is a costly intervention a, with additional consultant time for all ED major patients. An optimistic sensitivity analysis found RAT to cost £98,000 per QALY gained – far from being cost effective. The main impact of RAT is likely to be on hospital flow, not taken into account by the cohort model. The simulation model saw a reduction in 4-hour breeches from 10% to 8%. The committee concluded that RAT is a costly intervention that is probably not cost effective in general, although it might still have a positive impact on hospital flow in hospitals operating at sub-optimal levels of efficiency within the emergency department. Extended hours for consultants in Acute Medical Units (AMU) The model compared consultant assessment available in the AMU 08:00-18:00 with consultant assessment available in the AMU 08:00-22:00. Therefore, the intervention involves the presence of a consultant to assess and treat on the AMU for an additional 4 hours in the evenings, 7 days a week. This uses additional resources in terms of consultant time at an incremental cost to normal care. The results of the cohort model found that extended hours on the AMU was cost increasing with a small impact on quality-adjusted life-years. However, the QALYs gained were not large enough in the base case or optimistic sensitivity analysis to allow an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio under the £20,000 threshold, £45,500 per QALY gained in the base case and £25,500 in the optimistic treatment effects sensitivity analysis. The committee noted the results of the cohort model with an ICER close to the £20,000 threshold in the sensitivity analysis. However, they also noted that extended hours in the AMU was likely to have an impact on hospital flow, not taken into account by the cohort model. However, the AMU could not be properly assessed by the simulation model because too many runs would be required. The committee noted that the intervention allows earlier decision making, potentially avoiding an overnight admission or facilitating earlier discharge. They also noted that extended hours in the AMU could have a positive impact on the hospital flow and patient outcomes, and therefore may be cost-effective at local level. However, extended hours to the AMU should only be implemented alongside local evaluation. Conclusion The committee felt that early consultant assessment could be cost effective in some settings. It is associated with some clinical benefit and, in some settings, the cost might be completely offset by savings from increased efficiencies in the hospital pathway. However, it was agreed that this would not be the case nationwide and any intervention should only be implemented at the local level alongside evaluation. For some Trusts, the resource impact of this recommendation will be more hours of consultant time in the AMU and other high care units. This should be partially offset by reduced length of stay and fewer complications. Some Trusts might want to disinvest in RAT, which would mean savings in terms of ED consultant staff time. There are benefits of early consultant assessment that were not captured in the model and are difficult to quantify, including impact on quality of life from quicker diagnosis and more appropriate location of/better quality of death. Overall, the evidence was not very strong and therefore the committee felt that neither immediate consultant assessment, such as RAT, nor extended hours could be recommended. However, there is still a need for consultant assessment at the earliest practical opportunity. Current pragmatic recommendations from professional organisations recommend initial consultant review within 14 hours for patients admitted to acute medical units [Society for Acute Medicine{ ACT2015}, and within 12 hours for patients admitted to intensive care units [UK Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine{FICM2016}]. The committee concluded that in the absence of definitive evidence, these professional recommendations were reasonable, but should be subject to local audit and evaluation. |

| Quality of evidence |

Emergency department: One RCT was identified which was based in Australia and was graded low to moderate quality due to risk of bias and imprecision. The committee considered whether the study was applicable to a UK setting as in a non-UK setting, patients may present more frequently to secondary care as a first contact. However, the committee chose not to downgrade this study for indirectness as the model was applicable. The observational evidence was all graded as very low quality due to lack of randomisation and the presence of additional confounders, such as the intervention group also receiving point of care testing in addition to early consultant review. Acute medical unit: One observational study was identified and the outcomes were graded as very low quality due to risk of bias, imprecision and indirectness. There were some baseline differences in the conditions for which patients in both groups were being assessed and multivariate analysis had not been carried out. No evidence was identified for stroke care, intensive care or critical care units. Original health economic modelling was assessed to be directly applicable but still had potentially serious limitations due to the treatment effects being based on expert opinion, albeit conservative and informed by the guideline’s systematic review. Due to the quality of the evidence the committee decided to make a cautious recommendation for providers to consider consultant review within 14 hours. |

| Other considerations |

The committee noted that, in practice, many of the competencies required to implement a model of early consultant review may be delivered by other members of healthcare staff. However, it is the knowledge or expertise that the consultant brings to the assessment that is crucial. Consultants do not work in isolation and need support of other staff; therefore to implement, this will require reconfiguration of rotas and changes in the availability of healthcare professionals. The committee were aware of observational evidence across a range of healthcare settings which was not included in the review because of either the availability of higher quality evidence or because it did not meet the inclusion criteria for the review. The committee noted that this observational evidence supported their recommendations for early consultant involvement in these settings. Although no evidence was found on patient and/or carer satisfaction, the committee noted that it was probably the preference of patients to be seen quickly, spend minimal time in ED and AMU and receive an accurate assessment of their condition with appropriate admission and discharge decisions. The committee was interested in how early the consultant review should be to demonstrate an improvement in clinical outcome. The definitions for an early consultant review as presented in the evidence was highly variable, most of which were unclear and vague. For example, one study defined an early consultant review as a review within 24 hours, whereas another study defined an early consultant review as when a consultant was present 4 days out of 5 during the working week from 9am-5pm. The committee referred to the RCP’s Acute care toolkit 4 and the Society for Acute Medicine clinical quality standards: Delivering a 12-hour, 7-day consultant presence on the acute medical unit which includes the following 2 key recommendations:

It was felt by the committee that, although there was no evidence from other acute care units such as the CCU, HASU or ICU, this way of working could be extrapolated to those centres. Indeed, in some of these units it is already occurring, that is, PCI in ST elevation MI which is often performed by a consultant cardiologist, or the delivery of thrombolysis in patients with stroke being covered by a consultant stroke thrombolysis rota. The Academy of Royal Colleges provided a report called the benefits of consultant delivered care2. In this report they highlighted the benefits of consultant delivered care:

As part of the implementation of 7 day services, hospital trusts are expected to meet 10 clinical standards produced by NHS England. The standards were drawn up by the national medical director, Sir Bruce Keogh, and his colleagues at NHS England in 2013, informed by an Academy of Medical Royal Colleges report published in 2012. Trusts are expected to meet 4 priority standards by the end of this financial year. The standards are:

|

References

- 1.

- Reducing interns’ consecutive and weekly working hours significantly reduces medical errors made in intensive care units. Evidence-Based Healthcare and Public Health. 2005; 9(3):209–210

- 2.

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. The benefits of consultant-delivered care, 2012. Available from: https://www

.aomrc.org .uk/wp-content/uploads /2016/05/Benefits _consultant_delivered_care_1112.pdf - 3.

- Adams BD, Zeiler K, Jackson WO, Hughes B. Emergency medicine residents effectively direct inhospital cardiac arrest teams. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2005; 23(3):304–310 [PubMed: 15915402]

- 4.

- Adiguzel N, Karakurt Z, Mocin OY, Takir HB, Salturk C, Kargin F et al. Full-time ICU staff in the intensive care unit: does it improve the outcome? Turk Toraks Dergisi. 2015; 16(1):28–32 [PMC free article: PMC5783043] [PubMed: 29404074]

- 5.

- Aga H, Readhead D, Maccoll G, Thompson A. Fall in peptic ulcer mortality associated with increased consultant input, prompt surgery and use of high dependency care identified through peer-review audit. BMJ Open. 2012; 2(1):e000271 [PMC free article: PMC3289989] [PubMed: 22357569]

- 6.

- Agrawal S, Battula N, Barraclough L, Durkin D, Cheruvu CVN. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy service provision is feasible and safe in the current UK National Health Service. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2009; 91(8):660–664 [PMC free article: PMC2966242] [PubMed: 19686614]

- 7.

- Ahmed RM, Green T, Halmagyi GM, Lewis SJG. A new model for neurology care in the emergency department. Medical Journal of Australia. 2010; 192(1):30–32 [PubMed: 20047545]

- 8.

- Ali E, Chaila E, Hutchinson M, Tubridy N. The ‘hidden work’ of a hospital neurologist: 1000 consults later. European Journal of Neurology. 2010; 17(4):e28–e32 [PubMed: 20050903]

- 9.

- Anderson D, Golden B, Silberholz J, Harrington M, Hirshon JM. An empirical analysis of the effect of residents on emergency department treatment times. IIE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering. 2013; 3(3):171–180

- 10.

- Anderson ID, Woodford M, de Dombal FT, Irving M. Retrospective study of 1000 deaths from injury in England and Wales. BMJ. 1988; 296(6632):1305–1308 [PMC free article: PMC2545772] [PubMed: 3133060]

- 11.

- Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, White A, Popovich JJ, Committee on Manpower for Pulmonary and Critical Care Societies (COMPACCS). Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000; 284(21):2762–2770 [PubMed: 11105183]

- 12.

- Asha SE, Ajami A. Improvement in emergency department length of stay using an early senior medical assessment and streaming model of care: a cohort study. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2013; 25(5):445–451 [PubMed: 24099374]

- 13.

- Audit Commission for Local Authorities and the National Health Service in England and Wales. By accident or design: improving A & E services in England and Wales: national study. London. H.M.S.O., 1996. Available from: http://archive

.audit-commission .gov.uk/auditcommission /subwebs /publications/studies/studyPDF/1151 .pdf - 14.

- Barnes ML, Hussain SSM. Consultant-based otolaryngology emergency service: a five-year experience. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2011; 125(12):1225–1231 [PubMed: 21767430]

- 15.

- Beiri A, Alani A, Ibrahim T, Taylor GJS. Trauma rapid review process: efficient out-patient fracture management. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2006; 88(4):408–411 [PMC free article: PMC1964617] [PubMed: 16834866]

- 16.

- Bell D, Lambourne A, Percival F, Laverty AA, Ward DK. Consultant input in acute medical admissions and patient outcomes in hospitals in England: a multivariate analysis. PloS One. 2013; 8(4):e61476 [PMC free article: PMC3629209] [PubMed: 23613858]

- 17.

- Bewick T, Cooper VJ, Lim WS. Does early review by a respiratory physician lead to a shorter length of stay for patients with non-severe community-acquired pneumonia? Thorax. 2009; 64(8):709–712 [PubMed: 19386582]

- 18.

- Blunt MC, Burchett KR. Out-of-hours consultant cover and case-mix-adjusted mortality in intensive care. The Lancet. 2000; 356(9231):735–736 [PubMed: 11085695]

- 19.

- Bray BD, Ayis S, Campbell J, Hoffman A, Roughton M, Tyrrell PJ et al. Associations between the organisation of stroke services, process of care, and mortality in England: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013; 346:f2827 [PMC free article: PMC3650920] [PubMed: 23667071]

- 20.

- Brodie FG, Sprigg N. Current evidence for the management and early treatment of transient ischaemic attack. Primary Care Cardiovascular Journal. 2012; 5(1):37–39

- 21.

- Brown JJ, Sullivan G. Effect on ICU mortality of a full-time critical care specialist. Chest. 1989; 96(1):127–129 [PubMed: 2736969]

- 22.

- CADTH. Intensivist response time to a closed intensive care unit: patient benefits and harms and guidelines. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), 2014. Available from: https://www

.cadth.ca /media/pdf/htis/feb-2014 /RB0645%20Closed%20ICUs%20Final.pdf - 23.

- Calder FR, Jadhav V, Hale JE. The effect of a dedicated emergency theatre facility on emergency operating patterns. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 1998; 43(1):17–19 [PubMed: 9560500]

- 24.

- Capp R, Soremekun OA, Biddinger PD, White BA, Sweeney LM, Chang Y et al. Impact of physician-assisted triage on timing of antibiotic delivery in patients admitted to the hospital with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012; 43(3):502–508 [PubMed: 22244295]

- 25.

- Carberry M. Hospital emergency care teams: our solution to out of hours emergency care. Nursing in Critical Care. 2006; 11(4):177–187 [PubMed: 16869524]

- 26.

- Cariga P, Huang WHC, Ranta A. Safety and efficiency of non-contact first specialist assessment in neurology. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011; 124(1347):48–52 [PubMed: 22237567]

- 27.

- Carroll C, Zajicek J. Provision of 24 hour acute neurology care by neurologists: manpower requirements in the UK. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2004; 75(3):406–409 [PMC free article: PMC1738976] [PubMed: 14966156]

- 28.

- Casalino E, Wargon M, Peroziello A, Choquet C, Leroy C, Beaune S et al. Predictive factors for longer length of stay in an emergency department: a prospective multicentre study evaluating the impact of age, patient’s clinical acuity and complexity, and care pathways. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2014; 31(5):361–368 [PubMed: 23449890]

- 29.

- Cha WC, Shin SD, Song KJ, Jung SK, Suh GJ. Effect of an independent-capacity protocol on overcrowding in an urban emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009; 16(12):1277–1283 [PubMed: 19912131]

- 30.

- Chen J, Bellomo R, Flabouris A, Hillman K, Assareh H, Ou L. Delayed emergency team calls and associated hospital mortality: a multicenter study. Critical Care Medicine. 2015; 43(10):2059–2065 [PubMed: 26181217]

- 31.

- Christmas AB, Reynolds J, Hodges S, Franklin GA, Miller FB, Richardson JD et al. Physician extenders impact trauma systems. Journal of Trauma. 2005; 58(5):917–920 [PubMed: 15920403]

- 32.

- Christmas E, Johnson I, Locker T. The impact of 24 h consultant shop floor presence on emergency department performance: a natural experiment. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2013; 30(5):360–362 [PubMed: 22660466]

- 33.

- Clarke CE, Edwards J, Nicholl DJ, Sivaguru A, Davies P, Wiskin C. Ability of a nurse specialist to diagnose simple headache disorders compared with consultant neurologists. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2005; 76(8):1170–1172 [PMC free article: PMC1739753] [PubMed: 16024902]

- 34.

- Cohee BM, Hartzell JD, Shimeall WT. Achieving balance on the inpatient internal medicine wards: a performance improvement project to restructure resident work hours at a tertiary care center. Academic Medicine. 2014; 89(5):740–744 [PubMed: 24667506]

- 35.

- Cohen A, Bodenham A, Webster N. A review of 2000 consecutive ICU admissions. Anaesthesia. 1993; 48(2):106–110 [PubMed: 8460754]

- 36.

- Cooke M. Employing general practitioners in accident and emergency departments. Better to increase number of consultants in accident and emergency medicine. BMJ. 1996; 313(7057):628 [PMC free article: PMC2352061] [PubMed: 8806275]

- 37.

- Cooke MW, Kelly C, Khattab A, Lendrum K, Morrell R, Rubython EJ. Accident and emergency 24 hour senior cover-a necessity or a luxury? Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 1998; 15(3):181–184 [PMC free article: PMC1343061] [PubMed: 9639181]

- 38.

- Cutler LR, Hayter M, Ryan T. A critical review and synthesis of qualitative research on patient experiences of critical illness. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2013; 29(3):147–157 [PubMed: 23312486]

- 39.

- Dale J, Green J, Reid F, Glucksman E. Primary care in the accident and emergency department: I. Prospective identification of patients. BMJ. 1995; 311(7002):423–426 [PMC free article: PMC2550493] [PubMed: 7640591]

- 40.

- Daoust R, Paquet J, Lavigne G, Sanogo K, Chauny JM. Senior patients with moderate to severe pain wait longer for analgesic medication in EDs. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014; 32(4):315–319 [PubMed: 24439544]

- 41.

- Davis RA, Dinh MM, Bein KJ, Veillard AS, Green TC. Senior work-up assessment and treatment team in an emergency department: a randomised control trial. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2014; 26(4):343–349 [PubMed: 24935075]

- 42.

- Day CJ, Bellamy MC. Paracetamol poisoning. Care of the Critically Ill. 2005; 21(2):51–56

- 43.

- Denman-Johnson M, Bingham P, George S. A confidential enquiry into emergency hospital admissions on the Isle of Wight, UK. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1997; 51(4):386–390 [PMC free article: PMC1060506] [PubMed: 9328544]

- 44.

- Dhrampal A. Time to first review of new admissions to critical care by the consultant intensivist. Critical Care. 2015; 14:157

- 45.

- Edkins RE, Cairns BA, Hultman CS. A systematic review of advance practice providers in acute care: options for a new model in a burn intensive care unit. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2014; 72(3):285–288 [PubMed: 24509138]

- 46.

- Edwards T. How rapid assessment at triage can improve care outcomes. Emergency Nurse. 2011; 19(6):27–30 [PubMed: 22128577]

- 47.

- el Gaylani N, Weston CF, Shandall A, Penny WJ, Buchalter. Experience of a rapid access acute chest pain clinic. Irish Medical Journal. 1997; 90(4):139–140 [PubMed: 9267090]

- 48.

- Elmstahl S, Wahlfrid C. Increased medical attention needed for frail elderly initially admitted to the emergency department for lack of community support. Aging. 1999; 11(1):56–60 [PubMed: 10337444]

- 49.

- Evans K, Fulton B. Meeting the challenges of Acute Care Quality Indicators. Acute Medicine. 2011; 10(2):91–94 [PubMed: 22041611]

- 50.

- Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and Intensive Care Society. Guidelines for the provision of intensive care services, 2015. Available from: http://members

.ics.ac .uk/ICS/guidelines-and-standards.aspx - 51.

- Fisher EW, Moffat DA, Quinn SJ, Wareing MJ, Von Blumenthal H, Morris DP. Reduction in junior doctors’ hours in an otolaryngology unit: effects on the ‘out of hours’ working patterns of all grades. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1994; 76:(Suppl 5):232–235 [PubMed: 7979091]

- 52.

- FitzPatrick MK, Reilly PM, Laborde A, Braslow B, Pryor JP, Blount A et al. Maintaining patient throughput on an evolving trauma/emergency surgery service. Journal of Trauma. 2006; 60(3):481–488 [PubMed: 16531843]

- 53.

- Foster PW, Ritchie AWS, Jones DJ. Prospective analysis of scrotal pathology referrals - are referrals appropriate and accurate? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2006; 88(4):363–366 [PMC free article: PMC1964653] [PubMed: 16834856]

- 54.

- Gambier N, Simoneau G, Bihry N, Delcey V, Champion K, Sellier P et al. Efficacy of early clinical evaluation in predicting direct home discharge of elderly patients after hospitalization in internal medicine. Southern Medical Journal. 2012; 105(2):63–67 [PubMed: 22267091]

- 55.

- Garland A, Roberts D, Graff L. Twenty-four-hour intensivist presence: a pilot study of effects on intensive care unit patients, families, doctors, and nurses. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012; 185(7):738–743 [PubMed: 22246176]

- 56.

- Garner JP, Prytherch D, Senapati A, O’Leary D, Thompson MR. Sub-specialization in general surgery: the problem of providing a safe emergency general surgical service. Colorectal Disease. 2006; 8(4):273–277 [PubMed: 16630229]

- 57.

- Gaskell DJ, Lewis PA, Crosby DL, Roberts CJ, Fenn N, Roberts SM. Improving the primary management of emergency surgical admissions: a controlled trial. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1995; 77:(Suppl 5):239–241 [PubMed: 7486780]

- 58.

- Gershengorn HB, Wunsch H, Wahab R, Leaf DE, Brodie D, Li G et al. Impact of nonphysician staffing on outcomes in a medical ICU. Chest. 2011; 139(6):1347–1353 [PubMed: 21393397]

- 59.

- Gibbs RG, Newson R, Lawrenson R, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Diagnosis and initial management of stroke and transient ischemic attack across UK health regions from 1992 to 1996: experience of a national primary care database. Stroke. 2001; 32(5):1085–1090 [PubMed: 11340214]

- 60.

- Gilligan SG, Walters MW. Quality improvements in hospital flow may lead to a reduction in mortality. Clinical Governance. 2008; 13(1):26–34

- 61.

- Glasser JS, Zacher LL, Thompson JC, Murray CK. Determination of the internal medicine service’s role in emergency department length of stay at a military medical center. Military Medicine. 2009; 174(11):1163–1166 [PubMed: 19960823]

- 62.

- Gomez MA, Anderson JL, Karagounis LA, Muhlestein JB, Mooers FB. An emergency department-based protocol for rapidly ruling out myocardial ischemia reduces hospital time and expense: results of a randomized study (ROMIO). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1996; 28(1):25–33 [PubMed: 8752791]

- 63.

- Gomez-Soto FM, Puerto JL, Andrey JL, Fernandez FJ, Escobar MA, Garcia-Egido AA et al. Consultation between specialists in Internal Medicine and Family Medicine improves management and prognosis of heart failure. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008; 19(7):548–554 [PubMed: 19013386]

- 64.

- Gulli G, Peron E, Ricci G, Formaglio E, Micheletti N, Tomelleri G et al. Yield of ultra-rapid carotid ultrasound and stroke specialist assessment in patients with TIA and minor stroke: an Italian TIA service audit. Neurological Sciences. 2014; 35(12):1969–1975 [PubMed: 25086902]

- 65.

- Halfdanarson TR, Hogan WJ, Moynihan TJ. Oncologic emergencies: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006; 81(6):835–848 [PubMed: 16770986]

- 66.

- Harrison J. The work patterns of consultant psychiatrists: revisiting… how consultants manage their time. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007; 13(6):470–475

- 67.

- Harvey M, Al Shaar M, Cave G, Wallace M, Brydon P. Correlation of physician seniority with increased emergency department efficiency during a resident doctors’ strike. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2008; 121(1272):59–68 [PubMed: 18425155]

- 68.

- Hellawell GO, Kahn L, Mumtaz F. The European working time directive: implications for subspecialty acute care. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2005; 59(5):508–510 [PubMed: 15857343]

- 69.

- Helling TS, Kaswan S, Boccardo J, Bost JE. The effect of resident duty hour restriction on trauma center outcomes in teaching hospitals in the state of Pennsylvania. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2010; 69(3):607–612 [PubMed: 20838133]

- 70.

- Hoffman LA, Miller TH, Zullo TG, Donahoe MP. Comparison of 2 models for managing tracheotomized patients in a subacute medical intensive care unit. Respiratory Care. 2006; 51(11):1230–1236 [PubMed: 17067404]

- 71.

- Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Scharfenberg C, Zullo TG, Donahoe MP. Management of patients in the intensive care unit: comparison via work sampling analysis of an acute care nurse practitioner and physicians in training. American Journal of Critical Care. 2003; 12(5):436–443 [PubMed: 14503427]

- 72.

- Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Zullo TG, Scharfenberg C, Donahoe MP. Outcomes of care managed by an acute care nurse practitioner/attending physician team in a subacute medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2005; 14(2):121–130 [PubMed: 15728954]

- 73.

- Holzman MD, Elkins CC, Neuzil DF, Williams LFJ. Expanding the physician care team: its effect on patient care, resident function, and education. Journal of Surgical Research. 1994; 56(6):636–640 [PubMed: 7912293]

- 74.

- Hopkins A, Worboys F. Establishing community wound prevalence within an inner London borough: exploring the complexities. Journal of Tissue Viability. 2014; 23(4):121–128 [PubMed: 25467134]

- 75.

- Horwitz LI, Kosiborod M, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Changes in outcomes for internal medicine inpatients after work-hour regulations. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007; 147(2):97–103 [PubMed: 17548401]

- 76.

- Imperato J, Morris DS, Binder D, Fischer C, Patrick J, Sanchez LD et al. Physician in triage improves emergency department patient throughput. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2012; 7(5):457–462 [PubMed: 22865230]

- 77.

- Jarvis P, Davies T, Mitchell K, Taylor I, Baker M. Does rapid assessment shorten the amount of time patients spend in the emergency department? British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2014; 75(11):648–651 [PubMed: 25383437]

- 78.

- Jeune IL, Masterton-Smith C, Subbe CP, Ward D. ‘State of the nation’ - the society for acute medicine’s benchmarking audit 2013 (SAMBA ’13). Acute Medicine. 2013; 12(4):214–219 [PubMed: 24364052]

- 79.

- Jimenez JG, Murray MJ, Beveridge R, Pons JP, Cortes EA, Garrigos JB et al. Implementation of the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) in the Principality of Andorra: can triage parameters serve as emergency department quality indicators? CJEM. 2003; 5(5):315–322 [PubMed: 17466139]

- 80.

- Johansson B, Holmberg L, Berglund G, Brandberg Y, Hellbom M, Persson C et al. Reduced utilisation of specialist care among elderly cancer patients: a randomised study of a primary healthcare intervention. European Journal of Cancer. 2001; 37(17):2161–2168 [PubMed: 11677102]

- 81.

- Johnstone C, Harwood R, Gilliam A, Mitchell A. A clinical decisions unit improves emergency general surgery care delivery. Clinical Governance. 2015; 20(4):191–198

- 82.

- Jung B, Daurat A, De Jong A, Chanques G, Mahul M, Monnin M et al. Rapid response team and hospital mortality in hospitalized patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2016; 42(4):494–504 [PubMed: 26899584]

- 83.

- Kapur N, House A, Creed F, Feldman E, Friedman T, Guthrie E. General hospital services for deliberate self-poisoning: an expensive road to nowhere? Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1999; 75(888):599–602 [PMC free article: PMC1741387] [PubMed: 10621900]

- 84.

- Kawar E, DiGiovine B. MICU care delivered by PAs versus residents: do PAs measure up? JAAPA : Official Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2011; 24(1):36–41 [PubMed: 21261146]

- 85.

- Kendrick AS, Ciraulo DL, Radeker TS, Lewis PL, Richart CM, Maxwell RA et al. Trauma nurse specialists’ performance of advanced skills positively impacts surgical residency time constraints. American Surgeon. 2006; 72(3):224–227 [PubMed: 16553123]

- 86.

- Kennelly SP, Drumm B, Coughlan T, Collins R, O’Neill D, Romero-Ortuno R. Characteristics and outcomes of older persons attending the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. QJM. 2014; 107(12):977–987 [PubMed: 24935811]

- 87.

- Kent BD, Nadarajan P, Akasheh NB, Sulaiman I, Karim S, Cooney S et al. Improving venous thromboembolic disease prophylaxis in medical inpatients: a role for education and audit. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2011; 180(1):163–166 [PubMed: 20957521]

- 88.

- Kerr E, Arulraj N, Scott M, McDowall M, van Dijke M, Keir S et al. A telephone hotline for transient ischaemic attack and stroke: prospective audit of a model to improve rapid access to specialist stroke care. BMJ. 2010; 341:c3265 [PubMed: 20601699]

- 89.

- Khadjooi K, Dimopoulos C, Paterson J. The acute physicians unit in scarborough hospital. Acute Medicine. 2009; 8(3):132–135 [PubMed: 21603668]

- 90.

- Kirton OC, Folcik MA, Ivy ME, Calabrese R, Dobkin E, Pepe J et al. Midlevel practitioner workforce analysis at a university-affiliated teaching hospital. Archives of Surgery. 2007; 142(4):336–341 [PubMed: 17438167]

- 91.

- Kmietowicz Z. Patients admitted as emergencies should see consultant in 12 hours, NCEPOD recommends. BMJ. 2007; 335(7623):738–739 [PMC free article: PMC2018757] [PubMed: 17932173]

- 92.

- Laine C, Goldman L, Soukup JR, Hayes JG. The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993; 269(3):374–378 [PubMed: 8418344]

- 93.

- Lal NR, Murray UM, Petter EO, Desmond JS. Clinical consequences of misinterpretations of neuroradiologic CT scans by on-call radiology residents. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2000; 21(1):124–129 [PMC free article: PMC7976358] [PubMed: 10669236]

- 94.

- Lammers RL, Roiger M, Rice L, Overton DT, Cucos D. The effect of a new emergency medicine residency program on patient length of stay in a community hospital emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003; 10(7):725–730 [PubMed: 12837646]

- 95.

- Langhorne P, Williams BO, Gilchrist W, Dennis MS, Slattery J. A formal overview of stroke unit trials. Revista De Neurologia. 1995; 23(120):394–398 [PubMed: 7497198]

- 96.

- Laupland KB. Admission to hospital with community-onset bloodstream infection during the ‘after hours’ is not associated with an increased risk for death. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010; 42(11-12):862–865 [PubMed: 20662617]

- 97.

- Laurens N, Dwyer T. The impact of medical emergency teams on ICU admission rates, cardiopulmonary arrests and mortality in a regional hospital. Resuscitation. 2011; 82(6):707–712 [PubMed: 21411218]

- 98.

- Levy MM. Intensivists at night: putting resources in the right place. Critical Care. 2013; 17(5):1008 [PMC free article: PMC4057471] [PubMed: 24120020]

- 99.

- Lewis H, Purdie G. The blocked bed: a prospective study. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1988; 101(853):575–577 [PubMed: 3419687]

- 100.

- Lilly CM, McLaughlin JM, Zhao H, Baker SP, Cody S, Irwin RS et al. A multicenter study of ICU telemedicine reengineering of adult critical care. Chest. 2014; 145(3):500–507 [PubMed: 24306581]

- 101.

- Londero LS, Norgaard B, Houlind K. Patient delay is the main cause of treatment delay in acute limb ischemia: an investigation of pre- and in-hospital time delay. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2014; 9(1):56 [PMC free article: PMC4232613] [PubMed: 25400690]

- 102.

- Longsworth FG. Casualty transit time for 100 adult walk-in patients at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Medical Journal. 1990; 39(3):166–169 [PubMed: 2264330]

- 103.

- Magin P, Lasserson D, Parsons M, Spratt N, Evans M, Russell M et al. Referral and triage of patients with transient ischemic attacks to an acute access clinic: risk stratification in an Australian setting. International Journal of Stroke. 2013; 8(Suppl A100):81–89 [PubMed: 23490207]

- 104.

- Mahmood A, Sharif MA, Ali UZ, Khan MN. Time to hospital evaluation in patients of acute stroke for alteplase therapy. Rawal Medical Journal. 2009; 34(1):43–46

- 105.

- Manawadu D, Choyi J, Kalra L. The impact of early specialist management on outcomes of patients with in-hospital stroke. PloS One. 2014; 9(8):e104758 [PMC free article: PMC4140715] [PubMed: 25144197]

- 106.

- Marriott R, Horrocks J, House A, Owens D. Assessment and management of self-harm in older adults attending accident and emergency: a comparative cross-sectional study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003; 18(7):645–652 [PubMed: 12833309]

- 107.

- Martin I, Mason D, Stewart J, Mason M, Smith N, and Gill K. Emergency admissions: a journey in the right direction? London. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2015

- 108.

- Martin PJ, Young G, Enevoldson TP, Humphrey PR. Overdiagnosis of TIA and minor stroke: experience at a regional neurovascular clinic. QJM. 1997; 90(12):759–763 [PubMed: 9536340]

- 109.

- McManus RJ, Mant J, Davies MK, Davis RC, Deeks JJ, Oakes RAL et al. A systematic review of the evidence for rapid access chest pain clinics. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2002; 56(1):29–33 [PubMed: 11833553]

- 110.

- McNeill G, Brahmbhatt DH, Prevost AT, Trepte NJB. What is the effect of a consultant presence in an acute medical unit? Clinical Medicine. 2009; 9(3):214–218 [PMC free article: PMC4953605] [PubMed: 19634381]

- 111.

- Meyer SC, Miers LJ. Cardiovascular surgeon and acute care nurse practitioner: collaboration on postoperative outcomes. AACN Clinical Issues. 2005; 16(2):149–158 [PubMed: 15876882]

- 112.

- Meynaar IA, van der Spoel JI, Rommes JH, van Spreuwel-Verheijen M, Bosman RJ, Spronk PE. Off hour admission to an intensivist-led ICU is not associated with increased mortality. Critical Care. 2009; 13(3):R84 [PMC free article: PMC2717451] [PubMed: 19500333]

- 113.

- Mirza A, McClelland L, Daniel M, Jones N. The ENT emergency clinic: does senior input matter? Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2013; 127(1):15–19 [PubMed: 23171602]

- 114.

- Morris LL, Pfeifer P, Catalano R, Fortney R, Nelson G, Rabito R et al. Outcome evaluation of a new model of critical care orientation. American Journal of Critical Care. 2009; 18(3):252–260 [PubMed: 19234099]

- 115.

- Mullen P, Dawson A, White J, Anthony-Pillai M. Timing of first review of new ICU admissions by consultant intensivists in a UK district general hospital. Critical Care. 2009; 13(191):192

- 116.

- Munro J, Mason S, Nicholl J. Effectiveness of measures to reduce emergency department waiting times: a natural experiment. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006; 23:35–39 [PMC free article: PMC2564124] [PubMed: 16373801]

- 117.

- Murphy AW, Bury G, Plunkett PK, Gibney D, Smith M, Mullan E et al. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner versus usual medical care in an urban accident and emergency department: process, outcome, and comparative cost. BMJ. 1996; 312(7039):1135–1142 [PMC free article: PMC2350641] [PubMed: 8620132]

- 118.

- Murrell KL, Offerman SR, Kauffman MB. Applying lean: implementation of a rapid triage and treatment system. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011; 12:184–191 [PMC free article: PMC3099605] [PubMed: 21691524]

- 119.

- Newby DE, Fox KA, Flint LL, Boon NA. A ‘same day’ direct-access chest pain clinic: improved management and reduced hospitalization. QJM. 1998; 91(5):333–337 [PubMed: 9709466]

- 120.

- O’Connor PM, Steele JA, Dearden CH, Rocke LG, Fisher RB. The accident and emergency department as a single portal of entry for the reassessment of all trauma patients transferred to specialist units. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 1996; 13(1):9–10 [PMC free article: PMC1342596] [PubMed: 8821215]

- 121.

- O’Keeffe F, Cronin S, Gilligan P, O’Kelly P, Gleeson A, Houlihan P et al. Did not wait patient management strategy (DNW PMS) study. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2012; 29(7):550–553 [PubMed: 21673015]

- 122.

- Patel MS, Volpp KG, Small DS, Hill AS, Even-Shoshan O, Rosenbaum L et al. Association of the 2011 ACGME resident duty hour reforms with mortality and readmissions among hospitalized Medicare patients. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014; 312(22):2364–2373 [PMC free article: PMC5546100] [PubMed: 25490327]

- 123.

- Pourmand A, Lucas R, Pines JM, Shokoohi H, Yadav K. Bedside teaching on time to disposition improves length of stay for critically-ill emergency departments patients. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013; 14(2):137–140 [PMC free article: PMC3628461] [PubMed: 23599849]

- 124.

- Rafman H, Lim SN, Quek SC, Mahadevan M, Lim C, Lim A. Using systematic change management to improve emergency patients’ access to specialist care: the Big Squeeze. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2013; 30(6):447–453 [PubMed: 22753640]

- 125.

- Redmond AD, Buxton N. Consultant triage of minor cases in an accident and emergency department. Archives of Emergency Medicine. 1993; 10(4):328–330 [PMC free article: PMC1286043] [PubMed: 8110326]

- 126.

- Rothen HU, Stricker K, Einfalt J, Bauer P, Metnitz PGH, Moreno RP et al. Variability in outcome and resource use in intensive care units. Intensive Care Medicine. 2007; 33(8):1329–1336 [PubMed: 17541552]

- 127.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JN et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. The Lancet. 2007; 370(9596):1432–1442 [PubMed: 17928046]

- 128.

- Sakr Y, Moreira CL, Rhodes A, Ferguson ND, Kleinpell R, Pickkers P et al. The impact of hospital and ICU organizational factors on outcome in critically ill patients: results from the extended prevalence of infection in intensive care study. Critical Care Medicine. 2015; 43(3):519–526 [PubMed: 25479111]

- 129.

- Salazar A, Corbella X, Onaga H, Ramon R, Pallares R, Escarrabill J. Impact of a resident strike on emergency department quality indicators at an urban teaching hospital. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001; 8(8):804–808 [PubMed: 11483455]

- 130.

- Schultz H, Mogensen CB, Pedersen BD, Qvist N. Front-end specialists reduce time to a treatment plan for patients with acute abdomen. Danish Medical Journal. 2013; 60(9):A4703 [PubMed: 24001465]

- 131.

- Secor RM. Rapid triage assessment of low back pain. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 1983; 9(1):17–20 [PubMed: 6219236]

- 132.

- Shetty A, Gunja N, Byth K, Vukasovic M. Senior streaming assessment further evaluation after triage zone: a novel model of care encompassing various emergency department throughput measures. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2012; 24(4):374–382 [PubMed: 22862754]

- 133.

- Showkathali R, Davies JR, Sayer JW, Kelly PA, Aggarwal RK, Clesham GJ. The advantages of a consultant led primary percutaneous coronary intervention service on patient outcome. QJM. 2013; 106(11):989–994 [PubMed: 23737507]

- 134.

- Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Rosen AK, Romano PS, Itani KMF, Cen L et al. Prolonged hospital stay and the resident duty hour rules of 2003. Medical Care. 2009; 47(12):1191–1200 [PMC free article: PMC3279179] [PubMed: 19786912]

- 135.

- Soong C, High S, Morgan MW, Ovens H. A novel approach to improving emergency department consultant response times. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2013; 22(4):299–305 [PubMed: 23322751]

- 136.

- Spigos D, Freedy L, Mueller C. 24-hour coverage by attending physicians: a new paradigm. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 1996; 167(5):1089–1090 [PubMed: 8911155]

- 137.

- Stevens PE, Tamimi NA, Al-Hasani MK, Mikhail AI, Kearney E, Lapworth R et al. Non-specialist management of acute renal failure. QJM. 2001; 94(10):533–540 [PubMed: 11588212]

- 138.

- Svirsky I, Stoneking LR, Grall K, Berkman M, Stolz U, Shirazi F. Resident-initiated advanced triage effect on emergency department patient flow. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013; 45(5):746–751 [PubMed: 23777776]

- 139.

- Ting HH, Lee TH, Soukup JR, Cook EF, Tosteson AN, Brand DA et al. Impact of physician experience on triage of emergency room patients with acute chest pain at three teaching hospitals. American Journal of Medicine. 1991; 91(4):401–408 [PubMed: 1951384]

- 140.

- Traub SJ, Wood JP, Kelley J, Nestler DM, Chang YH, Saghafian S et al. Emergency department rapid medical assessment: overall effect and mechanistic considerations. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015; 48(5):620–627 [PubMed: 25769939]

- 141.

- Travers JP, Lee FC. Avoiding prolonged waiting time during busy periods in the emergency department: is there a role for the senior emergency physician in triage? European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006; 13(6):342–348 [PubMed: 17091056]

- 142.

- Vaghasiya MR, Murphy M, O’Flynn D, Shetty A. The emergency department prediction of disposition (EPOD) study. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2014; 17(4):161–166 [PubMed: 25112947]

- 143.

- Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Even-Shoshan O, Canamucio A et al. Mortality among patients in VA hospitals in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007; 298(9):984–992 [PubMed: 17785643]

- 144.

- Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Itani KMF, Bellini L et al. Did duty hour reform lead to better outcomes among the highest risk patients? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009; 24(10):1149–1155 [PMC free article: PMC2762498] [PubMed: 19455368]

- 145.

- Volpp KG, Small DS, Romano PS, Itani KMF, Rosen AK, Even-Shoshan O et al. Teaching hospital five-year mortality trends in the wake of duty hour reforms. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013; 28(8):1048–1055 [PMC free article: PMC3710388] [PubMed: 23592241]

- 146.

- Vosk A. Response of consultants to the emergency department: a preliminary report. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1998; 32(5):574–577 [PubMed: 9795320]

- 147.

- Walls J, Hunter N, Brasher PMA, Ho SGF. The DePICTORS study: discrepancies in preliminary interpretation of CT scans between on-call residents and staff. Emergency Radiology. 2009; 16(4):303–308 [PubMed: 19184142]

- 148.

- Wanklyn P, Hosker H, Pearson S, Belfield P. Slowing the rate of acute medical admissions. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 1997; 31(2):173–176 [PMC free article: PMC5420905] [PubMed: 9131518]

- 149.

- Ward D, Potter J, Ingham J, Percival F, Bell D. Acute medical care. The right person, in the right setting-first time: how does practice match the report recommendations? Clinical Medicine. 2009; 9(6):553–556 [PMC free article: PMC4952293] [PubMed: 20095297]

- 150.

- Ward NS, Afessa B, Kleinpell R, Tisherman S, Ries M, Howell M et al. Intensivist/patient ratios in closed ICUs: a statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Taskforce on ICU Staffing. Critical Care Medicine. 2013; 41(2):638–645 [PubMed: 23263586]

- 151.

- White AL, Armstrong PAR, Thakore S. Impact of senior clinical review on patient disposition from the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2010; 27(4):262–296 [PubMed: 20385673]

- 152.

- Wilcox ME, Chong CA, Niven DJ, Rubenfeld GD, Rowan KM, Wunsch H et al. Do intensivist staffing patterns influence hospital mortality following ICU admission? A systematic review and meta-analyses. Critical Care Medicine. 2013; 41(10):2253–2274 [PubMed: 23921275]

- 153.

- Wilcox ME, Harrison DA, Short A, Jonas M, Rowan KM. Comparing mortality among adult, general intensive care units in England with varying intensivist cover patterns: a retrospective cohort study. Critical Care. 2014; 18(4):491 [PMC free article: PMC4159542] [PubMed: 25123141]

- 154.

- Woods RA, Lee R, Ospina MB, Blitz S, Lari H, Bullard MJ et al. Consultation outcomes in the emergency department: exploring rates and complexity. CJEM. 2008; 10(1):25–31 [PubMed: 18226315]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Table 9Review protocol: Early versus late consultant review

| Review question: Is early consultant triage in the ED (RAT model) more clinically and cost effective than later consultant review? | |

|---|---|

| Objective | To determine if early consultant review at acute presentation improves patient outcomes and reduces rate of admission. |

| Rationale | Specialists ensure that patients are on the correct treatment pathway, moving along the pathway in a timely manner, and not subject to unexpected delays or complications. The first step in the process, determining the correct diagnosis and initial treatment, needs to be taken in a timely manner, as delays can compromise patient outcomes. The question is at what point is specialist involvement essential? At the point of admission, or following initial review and stabilisation by the other members of the clinical team? |

| Population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME |

| Intervention | Early consultant review |

| Comparison | Later consultant review (any time point that is later than the intervention) |

| Outcomes | Patient outcomes;

|

| Exclusion | |

| Search criteria |

The databases to be searched are: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library Date limits for search: None Language: English only |

| The review strategy | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Analysis |

Data synthesis of RCT data. Meta-analysis where appropriate will be conducted. Studies in the following subgroup populations will be included:

|

| Key papers | |

| Number of clinical questions | Max occupancy 85%, often at 95% ED / RAT model in ED, note time points (not enough staff at moments to implement) (PD ideal world seen within 1 hour by consultant). |

| HE questions | Crucial to conceptual. RF does diagnostic reviews (out of 10) for HE. |

| Review question: Is early consultant review in the AMU, ICU, HDU, CCU or Stroke Unit more clinically and cost effective than later consultant review? | |

|---|---|

| Objective | To determine if early consultant review at acute presentation improves patient outcomes and reduces rate of admission. |

| Rationale | Specialists ensure that patients are on the correct treatment pathway, moving along the pathway in a timely manner, and not subject to unexpected delays or complications. The first step in the process, determining the correct diagnosis and initial treatment, needs to be taken in a timely manner, as delays can compromise patient outcomes. The question is at what point is specialist involvement essential? At the point of admission, or following initial review and stabilisation by the other members of the clinical team? |

| Population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME - presenting to GP |

| Intervention | Early consultant review |

| Comparison | Later consultant review (any time point that is later than the intervention) |

| Outcomes | Patient outcomes;

|

| Exclusion | None |

| Search criteria |

The databases to be searched are: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library Date limits for search: None Language: English only |

| The review strategy | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Analysis |

Data synthesis of RCT data. Meta-analysis where appropriate will be conducted. Studies in the following subgroup populations will be included:

|

Appendix C. Forest plots

Emergency Department – RCT evidence

Emergency Department – Observational evidence

AMU – observational evidence

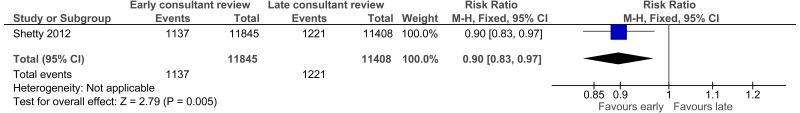

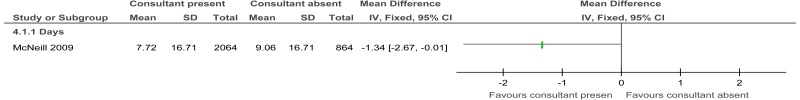

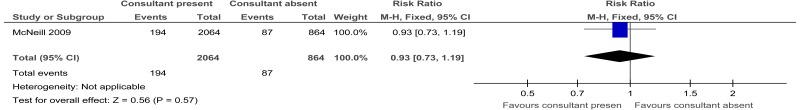

Figure 18Early versus late (Consultant present versus consultant absent) in AMU: length of stay (days)

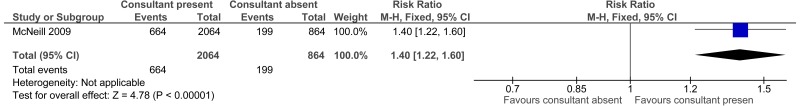

Figure 19Early versus late (Consultant present versus consultant absent) in AMU: percent discharged on day of admission

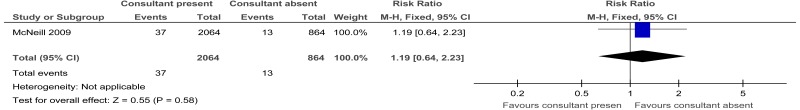

Figure 20Early versus late (Consultant present versus consultant absent) in AMU: percent of patients discharged within 24 hours and readmitted within 1 week for same clinical problem

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (560K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No studies were included.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 10Clinical evidence profile: Early versus late consultant review in ED (SWAT versus standard care control): RCT evidence

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Early (SWAT) | late consultant review (control) | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Proportion of patients who met NEAT | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

308/647 (47.6%) | 45.6% | RR 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 18 more per 1000 (from 36 fewer to 82 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| Proportion of admitted patients who met NEAT | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | Serious2 | none |

56/251 (22.3%) | 17.8% | RR 1.26 (0.86 to 1.83) | 46 more per 1000 (from 25 fewer to 148 more) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Proportion of discharged patients who met NEAT | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

252/396 (63.6%) | 62.5% | RR 1.02 (0.91 to 1.14) | 12 more per 1000 (from 56 fewer to 87 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| Number of patients admitted | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

251/647 (38.8%) | 37.7% | RR 1.03 (0.89 to 1.19) | 11 more per 1000 (from 41 fewer to 72 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| Number of patients discharged | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

396/647 (61.2%) | 62.3% | RR 0.98 (0.9 to 1.08) | 12 fewer per 1000 (from 62 fewer to 50 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed one MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Table 11Clinical evidence profile: Early versus late consultant review in ED: observational evidence

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Early consultant triage | late consultant triage | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Length of stay (minutes) (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | Serious3 | none | 608 | 683 | - | MD 68.3 lower (84.76 to 51.84 lower) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious2 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious3 | none |

2/608 (0.33%) | 0.2% | Peto OR 2.20 (0.23, 21.23) | 2 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 39 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

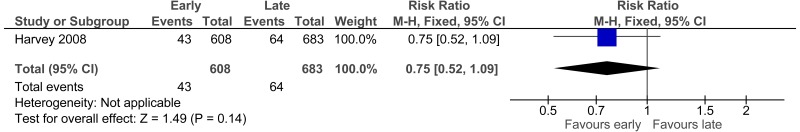

| 30 day unscheduled readmissions | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | Serious3 | none |

43/608 (7.1%) | 9.4% | RR 0.75 (0.52 to 1.09) | 23 fewer per 1000 (from 45 fewer to 8 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

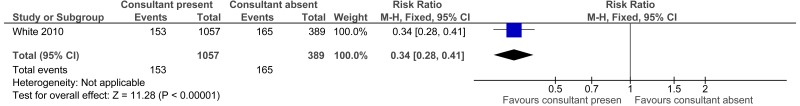

| Admitted | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

153/1057 (14.5%) | 42.4% | RR 0.34 (0.28 to 0.41) | 280 fewer per 1000 (from 250 fewer to 305 fewer) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

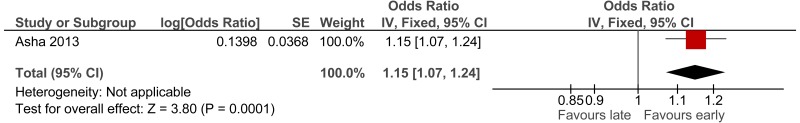

| % achieving NEAT | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | OR 1.15 (1.07 to 1.24) | 140 more per 1000 (from 70 more to 210 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | ||

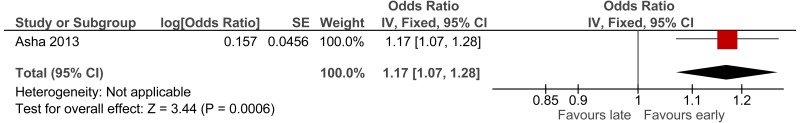

| % achieving NEAT of those discharged | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | Serious3 | none | - | OR 1.17 (1.07 to 1.28) | 160 more per 1000 (from 70 more to 250 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | ||

| % achieving NEAT of those admitted | ||||||||||||

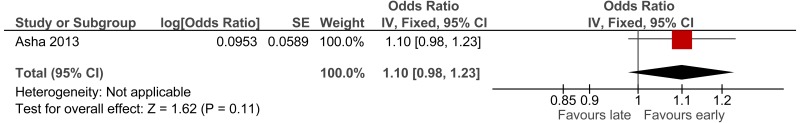

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | OR 1.1 (0.98 to 1.23) | 100 more per 1000 (from 20 fewer to 210 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | ||

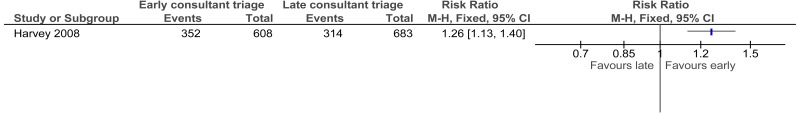

| % seen within recommended waiting times - Harvey 2008 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | Serious3 | none |

352/608 (57.9%) | 46% | RR 1.26 (1.13 to 1.4) | 120 more per 1000 (from 60 more to 184 more)) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

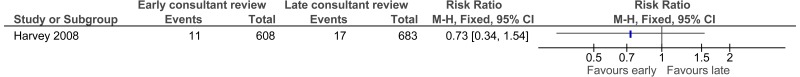

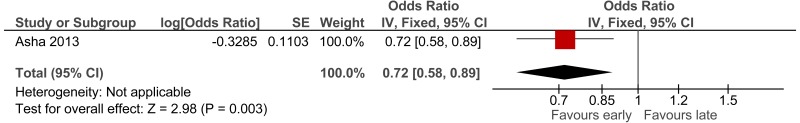

| Did not wait to be seen patients (Harvey 2008) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | Very serious3 | none |

11/608 (1.8%) | 2.5% | RR 0.73 (0.34-1.54) | 7 fewer per 1000 (from 16 fewer to 13 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Did not wait to be seen patients (Asha 2013) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | Serious3 | none | - | OR 0.72 (0.58 to 0.89) | 330 fewer (from 540 fewer to 110 fewer) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | ||

| Did not wait to be seen patients (Shetty 2012) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | no serious imprecision | none |

1137/11845 (9.6%) | 10.7% | RR 0.9 (0.83 to 0.97) | 11 fewer per 1000 (from 3 fewer to 18 fewer) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed one MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Table 12Clinical evidence profile: Early versus late consultant review in AMU (consultant present versus consultant absent): cohort study evidence

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Early (Consultant present) | Late (Consultant absent) | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Length of stay - Days (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 2064 | 864 | - | MD 1.34 lower (2.67 to 0.01 lower) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| % discharged on day of admission | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | Serious3 | none |

664/2064 (32.2%) | 23.0% | RR 1.4 (1.22-1.6) | 129 more per 1000 (from 71 more to 193 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| % patients discharged within 24 hours and readmitted within 1 week for same clinical problem | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | very serious3 | none |

37/2064 (1.8%) | 1.5% | RR 1.19 (0.64 to 2.23) | 3 more per 1000 (from 5 fewer to 18 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Mortality during admission | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | Serious1 | no serious inconsistency | Serious2 | Serious3 | none |

194/2064 (9.4%) | 10.1% | RR 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) | 7 fewer per 1000 (from 27 fewer to 19 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

The evidence is indirect as the exact time of consultant review was not reported.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed one MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 13Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| ADAMS 20053 | Incorrect setting and population (in-hospital cardiac arrests occurring hospital-wide). |

| ADIGUEZL 20154 | Incorrect comparison (pulmonary specialist versus intensivist). |

| AGA 20125 | Incorrect setting (surgical care). |

| AGRAWAL 20096 | Incorrect setting (general surgery). |

| AHMED 20107 | Incorrect setting (outpatient clinic). |