NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details29. Multidisciplinary team meetings

29.1. Introduction

Multidisciplinary team meetings and a multidisciplinary team care approach have been recommended in several published NICE guidelines about specific diseases and clinical conditions. The review question was posed in this case to find out if there is a more generalisable benefit to such a service to both patients and staff in the management of acute medical emergencies.

Multidisciplinary care can be found in many secondary care settings throughout the UK. There is no national standard for an MDT; indeed some of its success may be in the flexibility to suit each particular clinical area, however, good planning and communication are common themes throughout.

29.2. Review question: Do ward multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) improve processes and patient outcomes?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

29.3. Clinical evidence

Eleven studies were included in the review;15,16,20,21,30,38,58,59,83,84,101 these are summarised in Table 2 below. We searched for randomised trials comparing the effectiveness of an MDT process versus no MDT process. We did not identify any studies that compared multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) with no multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs). Nine randomised trials were identified that compared multidisciplinary care with no multidisciplinary care;15,16,21,30,38,58,59,83,84 this evidence was considered as indirect as the studies did not compare multidisciplinary team meetings with no multidisciplinary team meetings as specified in the protocol. There were 2 studies which compared multidisciplinary ward rounds with no multidisciplinary ward rounds20,101 which was considered as direct evidence in the evidence review as ward rounds is a type of meeting or gathering to enable MDT working.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

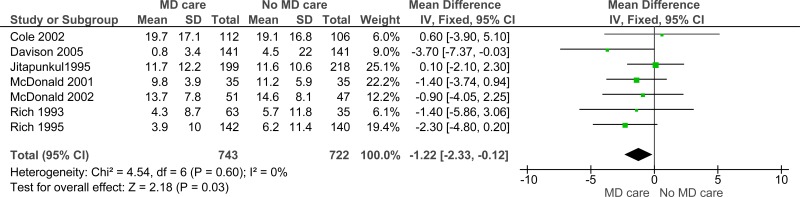

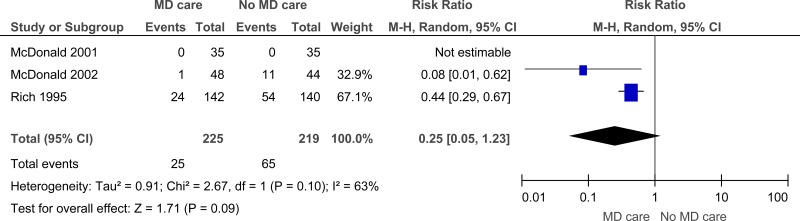

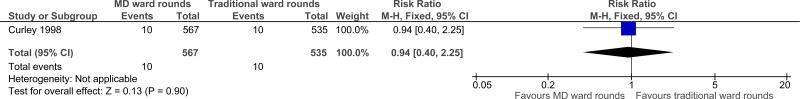

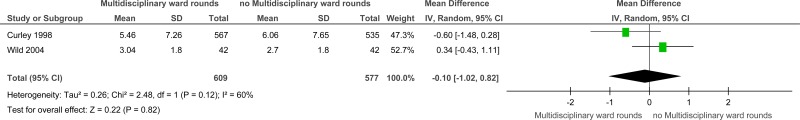

In our analysis, we have analysed studies comparing multidisciplinary care with no multidisciplinary care and studies comparing multidisciplinary ward rounds with no multidisciplinary ward rounds separately. Evidence from these studies are summarised in the GRADE clinical evidence profile (Table 3). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 3

Clinical evidence profile: Multidisciplinary care/interventions versus no multidisciplinary care/interventions.

Summary of included studies

Table 4

Clinical evidence profile: Multidisciplinary ward rounds versus no multidisciplinary ward rounds.

Outcomes that could not be analysed in Revman included:

- Quality of life [difference in mean score from baseline to 6 month follow-up] (No SD) (Cole 2006).SF-36, mental component (mean): Intervention group: 9.4; control group: 9.2; SF-36, physical component (mean): Intervention group: −2.9; control group: −2.7.

- Length of hospital stay (median, days) (No SD or IQR reported) (Cole 2006).Intervention group: 12.0; control group: 10.0.

- Health-related Quality of life (No SD) (Gwadry 2005).SF-36, PCS (physical) summary scores (mean): Intervention group: Improved from 30.52 to 37.15; control group: Improved from 29.13 to 37.38. SF-36, MCS (mental) summary scores (mean): Intervention group: Improved from 46.31 to 52.38; control group: Improved from 42.74 to 51.94.

29.4. Economic evidence

29.4.1. Published literature

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

29.4.2. Cost analysis

Hourly staffing costs for the core members of the MDT (medical consultant, registrar, staff nurse, pharmacist, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and social worker) comes to £429 (Table 5), or an incremental cost of £228 compared with the medical staff on their own.

Table 5

Costs of MDT staff.

MDT board round

We assumed a rather generous 10 minutes per patient per day summing to £266 for a 7.0 day stay (Table 6).

Table 6

Incremental results.

The included evidence on MDT care showed reductions in length of stay of 1.7 days per person. Based on the average excess bed day cost from NHS Reference Costs of £296, this would result in a saving of £494 per person. Overall, this indicated a net saving of £228 per patient.

MDT ward round

The evidence on MDT ward rounds showed a mean reduction of 0.6 bed days and this would save £177 per person (Table 6). The evidence also showed a reduction in readmissions of 165 fewer per 1000 for those with MDT care.

Again, we assumed 10 minutes per day for 7 days. On that basis, the cost of the intervention was £266 per patient. If the stays averted were short stays then the net cost savings would be £8.50. However, with more staff attending or higher grades of staff this could be cost increasing instead. If the readmissions averted were long stays then there would be a net saving of £374.

The cost impact is uncertain but if there are improved patient outcomes then it seems likely that it would be cost effective.

29.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

Multidisciplinary care versus no multidisciplinary care

Nine studies comprising 1424 people compared multidisciplinary care with no multidisciplinary care for improving outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that multidisciplinary care may provide a benefit in reduced length of hospital stay (7 studies, low quality), readmissions for chronic heart failure (3 studies, very low quality), readmissions all-cause (3 studies, very low quality) and quality of life (1 study, low quality). The evidence suggested that there was no effect on all-cause mortality (7 studies, very low quality).

Multidisciplinary care rounds versus no multidisciplinary ward rounds

Two studies comprising 1186 people compared multidisciplinary care rounds with traditional ward rounds for improving outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that there was no effect on mortality (in-hospital) (1 study, very low quality) and length of stay (2 studies, low quality).

Economic

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

29.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendation | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Mortality, avoidable adverse events (missed or delayed investigations and missed or delayed treatments), quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction and length of stay/time to discharge were considered by the committee to be critical outcomes. Readmission and staff satisfaction were considered to be important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

No studies were found on multidisciplinary team meetings but evidence was included on interdisciplinary ward rounds and multidisciplinary care. The definitions of these terms as used by the committee are noted in the introduction to this chapter. A total of 11 studies were identified for this review, which was split into interdisciplinary ward rounds and multidisciplinary care. There was evidence from 2 studies that compared interdisciplinary ward rounds with no interdisciplinary ward rounds. This was considered as direct evidence in the evidence review as ward rounds are a form of interdisciplinary meeting. The evidence suggested that there was no difference between the groups for the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and length of stay. No evidence was available for the outcomes of readmissions for congestive heart failure (CHF), readmissions (all-cause), quality of life, avoidable adverse events, patient and/or carer satisfaction and staff satisfaction. There was no evidence available for the comparison of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) with no MDTs. However, there was evidence from 9 randomised trials comparing multidisciplinary care with no multidisciplinary care. This evidence was considered as indirect, as the studies did not specifically compare MDTs with no MDTs as specified in the protocol. However, the committee considered that the concept of team working was inherent in the concept of multidisciplinary care and could be used to inform a recommendation. The evidence for multidisciplinary care suggested there may be a benefit for reduced length of hospital stay, readmissions for congestive heart failure (CHF) at 3 months, readmissions (all-cause) at 3 and 6 months and quality of life compared to no multidisciplinary care. The evidence suggested that there was no effect of multidisciplinary care on all-cause mortality. As there was heterogeneity in the results for the outcome of all-cause re-admissions, a sub-group analysis was conducted. The sub-group results suggested that there was benefit for patients with CHF but none for patients aged over 65 years admitted from the ED with major depression. The data for patients with major depression came from 1 study16 and the study authors suggested that the lack of benefit could be attributed to high patient attrition rate, low number of contacts between patients and psychiatrists, sub-optimal compliance with anti-depressant medications or possible contamination (or mixing) of the usual care group (patients in both the groups were managed on the same units by the same attending physicians). The committee also felt that patients with depression in this study might not be generalisable to patients with other medical emergencies, while recognising that depression could be a common problem in the latter group. Therefore, it was felt that patients with CHF were more likely to be representative of the population of interest that is, those with acute medical emergencies. No evidence was available for the outcomes avoidable adverse events, readmission within 30 days, patient and/or carer satisfaction and staff satisfaction. There was very little information about the frequency of meetings in the included studies. Only 1 study16 described the intervention team (comprising 2 geriatric psychiatrists, 2 geriatric internists and the study nurse) meeting after every 8-10 patients were enrolled in the intervention group to discuss delirium management problems. The committee were of the view that MDT care was predicated on effective communication between the various members, and should be focused on patient outcomes and progressing the patient journey. The frequency and formality of meetings should be tailored to the needs of the patient and would have to take into account the context in which care was being delivered. The committee felt that a strong recommendation was appropriate as the evidence was strong enough to show a consistent and likely generalisable benefit for multidisciplinary care over non-multidisciplinary care, particularly as the principles are well-established in current practice. However, variation in application suggests that standardisation of best practice would bring benefits, particularly for patients with complex conditions, and those with multimorbidity. The committee recommended that the multidisciplinary care should be co-ordinated meaning that it brings the different elements of a complex activity or organisation into a harmonious or efficient relationship. Multidisciplinary team meetings and multidisciplinary team care approach have been recommended in several published NICE guidelines about specific diseases and clinical conditions -Stroke: Diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) NICE guidelines [CG68];69 Hip fracture: The management of hip fracture in adults NICE guidelines [CG124]68 and Chronic heart failure: Management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care NICE guidelines [CG108].67 The committee noted that team composition and styles of practice could be quite diverse and might need to be adapted to particular situations and diseases. The need for multidisciplinary care should be determined on a case by case basis, where clinically appropriate. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

No economic evidence was identified for this question. Hourly staffing costs for the core members of the MDT (medical consultant, registrar, staff nurse, pharmacist, physiotherapist, occupational theraist and social worker) comes to £429, or an incremental cost of £228 compared with the medical staff on their own. The included evidence on MDT care showed reductions in length of stay of 1.7 days per person. Based on the average excess bed day cost from NHS Reference Costs of £296, this would result in a net saving overall of £228 per patient. The evidence on MDT ward rounds showed a mean reduction of 0.6 bed days and a reduction in readmissions of 165 fewer per 1000. By our calculations this would offset most of the cost of the intervention and most likely be cost saving, although this would depend on the time spent per patient and the number and grade of staff involved. Other considerations were the additional benefits shown from the evidence of reduced mortality and improved quality of life. Therefore the committee concluded that multidisciplinary team meetings would be cost-effective and may be cost saving for the management of acutely ill medical inpatients. Most hospitals will provide multidisciplinary care. For those hospitals that need to extend multidisciplinary care, e.g. through multidisciplinary board rounds, there will be an investment of time from those professionals (including doctors, nurses, pharmacists and therapists). However, this cost should be at least partly offset by savings in terms of reductions in length of stay and possibly readmission. |

| Quality of evidence |

The quality of the evidence for studies comparing multidisciplinary care with no multidisciplinary care was graded from low to very low, mainly due to risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency and indirectness. The evidence was downgraded for indirectness as the studies did not focus on multidisciplinary team meetings, but instead at multidisciplinary care. There was heterogeneity for the outcome of re-admissions (all cause) but the evidence was not downgraded as it was sufficiently explained by the sub-group analysis by disease condition. One study examined patients with major depression and the other 2 studies were patients with chronic heart failure. Patients with depression are suspected to have a longer and more complex pathway than patients with chronic heart failure which could reflect in readmissions. The quality of evidence for studies comparing multidisciplinary ward rounds with traditional ward rounds was graded low to very low quality; this was due to risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There were no economic studies included in the review. |

| Other considerations |

Multidisciplinary care is already common practice, although not uniform, throughout the country. While the principle of multidisciplinary care and therefore the recommendation should be well-accepted, practical implementation requires planning and effective communication. It should be relatively straightforward to implement but regular review of this approach will be important to ensure effective communication between team members to maximise effective use of health professional time and benefits to patients. Regular scheduling of MDTs in the elective setting (for example, oncology and transplantation) may need adaptation for emergency care, with a smaller group conducting daily reviews and incorporating external expertise either on an ad hoc basis or at planned but less frequent intervals. It will be important to ensure there are no unnecessary delays and that the care is value-added. It is often assumed that this form of working is easy and simple to implement. To achieve effective MDT working some training is required to ensure members understand and value the roles of each other and develop an ethos of working as a member of a team, particularly focusing on providing the best possible outcomes for patients. Therefore, logistical difficulties in arranging MDTs should not be resolved at the expense of timely patient care. The MDT should understand the roles and remit of the wider healthcare team to ensure that multidisciplinary care can be effective and timely. There was no evidence on the frequency of meetings. In the context of acute medical emergencies the committee noted that staff would meet as required by the current situation (which would probably be at least once daily). Once patients have moved along the pathway and their condition(s) stabilised, management may come under specific NICE guidelines for particular clinical conditions; these should be consulted for information on multidisciplinary care. It is important that the benefits achieved through MDT care should not be restricted to weekdays and office hours. Such care should be provided 7 days per week to ensure equity of care and timely transit of patients along their therapeutic pathway and across the continuum of secondary, community and social care; otherwise, this would cause delays resulting in the inevitable Monday effect when hospital are strained by increased demand and the reduced capacity due to the lack of progress in patient management over the weekend. |

References

- 1.

- Participating in interdisciplinary care planning. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2013; 43:(Suppl 2):S29

- 2.

- Ahmed A. Quality and outcomes of heart failure care in older adults: Role of multidisciplinary disease-management programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002; 50(9):1590–1593 [PubMed: 12383160]

- 3.

- Austin J, Williams WR, Hutchison S. Multidisciplinary management of elderly patients with chronic heart failure: five year outcome measures in death and survivor groups. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2009; 8(1):34–39 [PubMed: 18534911]

- 4.

- Bearne LM, Byrne AM, Segrave H, White CM. Multidisciplinary team care for people with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology International. 2016; 36(3):311–324 [PubMed: 26563338]

- 5.

- Britton A, Russell R. Multidisciplinary team interventions for delirium in patients with chronic cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000; Issue 2:CD000395. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000395 [PubMed: 10796541] [CrossRef]

- 6.

- Callens M, van den Oever R. Quality improvement in cancer care: the multidisciplinary oncological consultation. Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 2006; 106(5):480–484 [PubMed: 17168255]

- 7.

- Cameron ID, Fairhall N, Langron C, Lockwood K, Monaghan N, Aggar C et al. A multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trial. BMC Medicine. 2013; 11:65 [PMC free article: PMC3751685] [PubMed: 23497404]

- 8.

- Cao V, Horn F, Laren T, Scott L, Giri P, Hidalgo D et al. 1080: patient-centered structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds in the medical ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2016; 44(12 Suppl 1):346 [PubMed: 29088002]

- 9.

- Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department-the DEED II study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(9):1417–1423 [PubMed: 15341540]

- 10.

- Capomolla S, Febo O, Ceresa M, Caporotondi A, Guazzotti G, La Rovere M et al. Cost/utility ratio in chronic heart failure: comparison between heart failure management program delivered by day-hospital and usual care. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002; 40(7):1259–1266 [PubMed: 12383573]

- 11.

- Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Lotfi-Jam K, Schofield P, Aranda S. Multidisciplinary care in cancer: do the current research outputs help? European Journal of Cancer Care. 2010; 19(4):434–441 [PubMed: 20105225]

- 12.

- Chan WS, Whitford DL, Conroy R, Gibney D, Hollywood B. A multidisciplinary primary care team consultation in a socio-economically deprived community: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2011; 11:15 [PMC free article: PMC3032651] [PubMed: 21261966]

- 13.

- Chock MM, Lapid MI, Atherton PJ, Kung S, Sloan JA, Richardson JW et al. Impact of a structured multidisciplinary intervention on quality of life of older adults with advanced cancer. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013; 25(12):2077–2086 [PMC free article: PMC4364551] [PubMed: 24001635]

- 14.

- Clark MM, Rummans TA, Atherton PJ, Cheville AL, Johnson ME, Frost MH et al. Randomized controlled trial of maintaining quality of life during radiotherapy for advanced cancer. Cancer. 2013; 119(4):880–887 [PMC free article: PMC4405146] [PubMed: 22930253]

- 15.

- Cole MG, McCusker J, Bellavance F, Primeau FJ, Bailey RF, Bonnycastle MJ et al. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of delirium in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2002; 167(7):753–759 [PMC free article: PMC126506] [PubMed: 12389836]

- 16.

- Cole MG, McCusker J, Elie M, Dendukuri N, Latimer E, Belzile E. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of depression in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006; 174(1):38–44 [PMC free article: PMC1319344] [PubMed: 16330624]

- 17.

- Collard AF, Bachman SS, Beatrice DF. Acute care delivery for the geriatric patient: an innovative approach. QRB Quality Review Bulletin. 1985; 11(6):180–185 [PubMed: 3939598]

- 18.

- Connolly MJ, Broad JB, Boyd M, Kerse N, Foster S, Lumley T. Cluster-randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a multidisciplinary intervention package for reducing disease-specific hospitalisations from long term care (LTC). Age and Ageing. 2014; 43:(Suppl 2):ii19 [PubMed: 27021357]

- 19.

- Copperman N, Haas T, Arden MR, Jacobson MS. Multidisciplinary intervention in adolescents with cardiovascular risk factors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997; 817:199–207 [PubMed: 9239189]

- 20.

- Curley C, McEachern JE, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Medical Care. 1998; 36:(Suppl 8):AS4–12 [PubMed: 9708578]

- 21.

- Davison J, Bond J, Dawson P, Steen IN, Kenny RA. Patients with recurrent falls attending Accident & Emergency benefit from multifactorial intervention-a randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 2005; 34(2):162–168 [PubMed: 15716246]

- 22.

- Der Y. Multidisciplinary rounds in our ICU: improved collaboration and patient outcomes. Critical Care Nurse. 2009; 29(4):84–83 [PubMed: 19648602]

- 23.

- Ellrodt G, Glasener R, Cadorette B, Kradel K, Bercury C, Ferrarin A et al. Multidisciplinary rounds (MDR): an implementation system for sustained improvement in the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. Critical Pathways in Cardiology. 2007; 6(3):106–116 [PubMed: 17804970]

- 24.

- Fakih MG, Dueweke C, Meisner S, Berriel-Cass D, Savoy-Moore R, Brach N et al. Effect of nurse-led multidisciplinary rounds on reducing the unnecessary use of urinary catheterization in hospitalized patients. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008; 29(9):815–819 [PubMed: 18700831]

- 25.

- Flikweert ER, Izaks GJ, Knobben BAS, Stevens M, Wendt K. The development of a comprehensive multidisciplinary care pathway for patients with a hip fracture: design and results of a clinical trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014; 15:188 [PMC free article: PMC4053577] [PubMed: 24885674]

- 26.

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine. United States 2008; 11(2):180–190 [PubMed: 18333732]

- 27.

- Garrubba M, Turner T, Grieveson C. Multidisciplinary care for tracheostomy patients: a systematic review. Critical Care. 2009; 13(6):R177 [PMC free article: PMC2811928] [PubMed: 19895690]

- 28.

- Gray D, Armstrong CD, Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Zhang W. Cost-effectiveness of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care for complex patients: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Canadian Family Physician. 2010; 56(1):e20–e29 [PMC free article: PMC2809192] [PubMed: 20090057]

- 29.

- Gums JG, Yancey J, Hamilton CA, Kubilis PS. A randomized, prospective study measuring outcomes after antibiotic therapy intervention by a multidisciplinary consult team. Pharmacotherapy. 1999; 19(12):1369–1377 [PubMed: 10600085]

- 30.

- Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y, Brown JE, Marchiori G, Guyatt G. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2005; 150(5):982 [PubMed: 16290975]

- 31.

- Hays RD, Eastwood JA, Kotlerman J, Spritzer KL, Ettner SL, Cowan M. Health-related quality of life and patient reports about care outcomes in a multidisciplinary hospital intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006; 31(2):173–178 [PubMed: 16542132]

- 32.

- Hendriks MRC, van Haastregt JCM, Diederiks JPM, Evers SMAA, Crebolder HFJM, van Eijk JT. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a multidisciplinary intervention programme to prevent new falls and functional decline among elderly persons at risk: design of a replicated randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN64716113]. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5:6 [PMC free article: PMC546206] [PubMed: 15651990]

- 33.

- Hendry GJ, Watt GF, Brandon M, Friel L, Turner DE, Lorgelly PK et al. The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary foot care program for children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an exploratory trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2013; 45(5):467–476 [PubMed: 23571642]

- 34.

- Hickman LD, Phillips JL, Newton PJ, Halcomb EJ, Al Abed N, Davidson PM. Multidisciplinary team interventions to optimise health outcomes for older people in acute care settings: a systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015; 61(3):322–329 [PubMed: 26255065]

- 35.

- Holland R, Battersby J, Harvey I, Lenaghan E, Smith J, Hay L. Systematic review of multidisciplinary interventions in heart failure. Heart. 2005; 91(7):899–906 [PMC free article: PMC1769009] [PubMed: 15958358]

- 36.

- Hunley C, Dyson J, Burkhalter M, Hawkins N, Rucks G, Jones E et al. 1185: implementing an early mobility program in a multisystem ICU: a multidisciplinary team approach. Critical Care Medicine. 2016; 44(12 Suppl 1):372

- 37.

- Jaarsma T. Nurse led, multidisciplinary intervention in chronic heart failure. Heart. 1999; 81(6):676 [PMC free article: PMC1729056] [PubMed: 10979717]

- 38.

- Jitapunkul S, Nuchprayoon C, Aksaranugraha S, Chaiwanichsiri D, Leenawat B, Kotepong W et al. A controlled clinical trial of multidisciplinary team approach in the general medical wards of Chulalongkorn Hospital. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 1995; 78(11):618–623 [PubMed: 8576674]

- 39.

- Johansson G, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedstrom G. Multidisciplinary team, working with elderly persons living in the community: a systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 17(2):101–116 [PubMed: 19466676]

- 40.

- Johnson V, Mangram A, Mitchell C, Lorenzo M, Howard D, Dunn E. Is there a benefit to multidisciplinary rounds in an open trauma intensive care unit regarding ventilator-associated pneumonia? American Surgeon. 2009; 75(12):1171–1174 [PubMed: 19999906]

- 41.

- Ke KM, Blazeby JM, Strong S, Carroll FE, Ness AR, Hollingworth W. Are multidisciplinary teams in secondary care cost-effective? A systematic review of the literature. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2013; 11(1):7 [PMC free article: PMC3623820] [PubMed: 23557141]

- 42.

- Kim JH, Ahn JB. Review on history and current practices of cancer multidisciplinary care. Journal of the Korean Medical Association. 2016; 59(2):88–94

- 43.

- Kominski G, Andersen R, Bastani R, Gould R, Hackman C, Huang D et al. UPBEAT: the impact of a psychogeriatric intervention in VA medical centers. Unified psychogeriatric biopsychosocial evaluation and treatment. Medical Care. 2001; 39(5):500–512 [PubMed: 11317098]

- 44.

- Koshman SL, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Shibata M, Rowe B, Choy JB et al. Design of a randomized trial of a multidisciplinary team heart failure rapid referral program: Heart failure Evaluation - Acute Referral Team Trial (HEARTT). Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal. 2007; 140(5):306–311

- 45.

- Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, Vincent C, Green JSA, Sevdalis N. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011; 18(8):2116–2125 [PubMed: 21442345]

- 46.

- Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. The Lancet. 2011; 377(9778):1693–1702 [PubMed: 21571152]

- 47.

- Lapid MI, Atherton PJ, Kung S, Cheville AL, McNiven M, Sloan JA et al. Does gender influence outcomes from a multidisciplinary intervention for quality of life designed for patients with advanced cancer? Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013; 21(9):2485–2490 [PubMed: 23609927]

- 48.

- Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Brown PD, Frost MH, Johnson ME, Huschka MM et al. Improving the quality of life of geriatric cancer patients with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2007; 5(2):107–114 [PubMed: 17578061]

- 49.

- Lemstra M, Stewart B, Olszynski WP. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary intervention in the treatment of migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Headache. 2002; 42(9):845–854 [PubMed: 12390609]

- 50.

- Leventhal ME, Denhaerynck K, Brunner-LaRocca H, Burnand B, Conca A, Bernasconi AT et al. Swiss Interdisciplinary management programme for heart failure (SWIM-HF): a randomised controlled trial study of an outpatient inter-professional management programme for heart failure patients in Switzerland. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2011; 141(March):w13171 [PubMed: 21384285]

- 51.

- Licata J, Aneja RK, Kyper C, Spencer T, Tharp M, Scott M et al. A foundation for patient safety: phase I implementation of interdisciplinary bedside rounds in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse. 2013; 33(3):89–91 [PubMed: 23727856]

- 52.

- Lincoln NB, Walker MF, Dixon A, Knights P. Evaluation of a multiprofessional community stroke team: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2004; 18(1):40–47 [PubMed: 14763718]

- 53.

- Lu Y, Loffroy R, Lau JYW, Barkun A. Multidisciplinary management strategies for acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. British Journal of Surgery. 2014; 101(1):e34–e50 [PubMed: 24277160]

- 54.

- Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Gafni A, Roberts J, Weir R, Thabane L et al. The effects and costs of a multifactorial and interdisciplinary team approach to falls prevention for older home care clients ‘at risk’ for falling: a randomized controlled trial. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2010; 29(1):139–161 [PubMed: 20202271]

- 55.

- Marra CA, Cibere J, Grubisic M, Grindrod KA, Gastonguay L, Thomas JM et al. Pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis: a multidisciplinary intervention for knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 2012; 64(12):1837–1845 [PubMed: 22930542]

- 56.

- Mattila R, Malmivaara A, Kastarinen M, Kivela SL, Nissinen A. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2003; 17(3):199–205 [PubMed: 12624611]

- 57.

- McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Reid A, Davies M et al. An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: a cluster randomized trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015; 18(11):962–969 [PMC free article: PMC4638201] [PubMed: 26305992]

- 58.

- McDonald K, Ledwidge M, Cahill J, Kelly J, Quigley P, Maurer B et al. Elimination of early rehospitalization in a randomized, controlled trial of multidisciplinary care in a high-risk, elderly heart failure population: the potential contributions of specialist care, clinical stability and optimal angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor dose at discharge. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2001; 3(2):209–215 [PubMed: 11246059]

- 59.

- McDonald K, Ledwidge M, Cahill J, Quigley P, Maurer B, Travers B et al. Heart failure management: multidisciplinary care has intrinsic benefit above the optimization of medical care. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2002; 8(3):142–148 [PubMed: 12140806]

- 60.

- McMurray JJV, Dargie HJ, Reid JL, Morrison CE, Ford I. A randomised controlled trial of nurse-led multi-disciplinary intervention to improve quality of life and reduce hospital re-admission in chronic heart failure. Health Bulletin. 1996; 54(6):522

- 61.

- Melin AL. A randomized trial of multidisciplinary in-home care for frail elderly patients awaiting hospital discharge. Aging. 1995; 7(3):247–250 [PubMed: 8547388]

- 62.

- Metzelthin SF, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Ambergen AW, Hobma SO, Sipers W et al. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary primary care approach to reduce disability in community dwelling frail older people: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013; 347:f5264 [PMC free article: PMC3769159] [PubMed: 24022033]

- 63.

- Mitchell GK, Brown RM, Erikssen L, Tieman JJ. Multidisciplinary care planning in the primary care management of completed stroke: a systematic review. BMC Family Practice. 2008; 9:44 [PMC free article: PMC2518150] [PubMed: 18681977]

- 64.

- Momsen AM, Rasmussen JO, Nielsen CV, Iversen MD, Lund H. Multidisciplinary team care in rehabilitation: an overview of reviews. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2012; 44(11):901–912 [PubMed: 23026978]

- 65.

- Mudge AM, Maussen C, Duncan J, Denaro CP. Improving quality of delirium care in a general medical service with established interdisciplinary care: a controlled trial. Internal Medicine Journal. 2013; 43(3):270–277 [PubMed: 22646754]

- 66.

- Naglie G, Tansey C, Kirkland JL, Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Detsky AS, Etchells E et al. Interdisciplinary inpatient care for elderly people with hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2002; 167(1):25–32 [PMC free article: PMC116636] [PubMed: 12137074]

- 67.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic heart failure: the management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE clinical guideline 108. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG108/ - 68.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. The management of hip fracture in adults. NICE clinical guideline 124. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2011. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG124 - 69.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). NICE clinical guideline 68. London. Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG68 [PubMed: 21698846] - 70.

- Nazir A, Unroe K, Tegeler M, Khan B, Azar J, Boustani M. Systematic review of interdisciplinary interventions in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013; 14(7):471–478 [PubMed: 23566932]

- 71.

- Ng L, Khan F. Multidisciplinary care for adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009; Issue 4:CD007425. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007425.pub2 [PubMed: 19821416] [CrossRef]

- 72.

- Nikolaus T, Bach M. Preventing falls in community-dwelling frail older people using a home intervention team (HIT): results from the randomized Falls-HIT trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003; 51(3):300–305 [PubMed: 12588572]

- 73.

- Nikolaus T, Specht-Leible N, Bach M, Oster P, Schlierf G. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and home intervention in the care of hospitalized patients. Age and Ageing. 1999; 28(6):543–550 [PubMed: 10604506]

- 74.

- O’Leary KJ, Buck R, Fligiel HM, Haviley C, Slade ME, Landler MP et al. Structured interdisciplinary rounds in a medical teaching unit: improving patient safety. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011; 171(7):678–684 [PubMed: 21482844]

- 75.

- Pannick S, Davis R, Ashrafian H, Byrne BE, Beveridge I, Athanasiou T et al. Effects of interdisciplinary team care interventions on general medical wards: a systematic review. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015; 175(8):1288–1298 [PubMed: 26076428]

- 76.

- Peeters GMEE, de Vries OJ, Elders PJM, Pluijm SMF, Bouter LM, Lips P. Prevention of fall incidents in patients with a high risk of falling: design of a randomised controlled trial with an economic evaluation of the effect of multidisciplinary transmural care. BMC Geriatrics. 2007; 7:15 [PMC free article: PMC1933430] [PubMed: 17605771]

- 77.

- Pieper MJC, Francke AL, van der Steen JT, Scherder EJA, Twisk JWR, Kovach CR et al. Effects of a stepwise multidisciplinary intervention for challenging behavior in advanced dementia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016; 64(2):261–269 [PubMed: 26804064]

- 78.

- Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, Corcoran N, Tran B, Bowden P et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2016; 42:56–72 [PubMed: 26643552]

- 79.

- Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006; 61(2):176–181 [PubMed: 16510862]

- 80.

- Pope G, Wall N, Peters CM, O’Connor M, Saunders J, O’Sullivan C et al. Specialist medication review does not benefit short-term outcomes and net costs in continuing-care patients. Age and Ageing. 2011; 40(3):307–312 [PubMed: 20817937]

- 81.

- Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004; 164(1):83–91 [PubMed: 14718327]

- 82.

- Reuben DB, Borok GM, Wolde-Tsadik G, Ershoff DH, Fishman LK, Ambrosini VL et al. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the care of hospitalized patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995; 332(20):1345–1350 [PubMed: 7715645]

- 83.

- Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995; 333(18):1190–1195 [PubMed: 7565975]

- 84.

- Rich MW, Vinson JM, Sperry JC, Shah AS, Spinner LR, Chung MK et al. Prevention of readmission in elderly patients with congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, randomized pilot study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1993; 8(11):585–590 [PubMed: 8289096]

- 85.

- Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, Frost MH, Bostwick JM, Atherton PJ et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006; 24(4):635–642 [PubMed: 16446335]

- 86.

- Santschi V, Lord A, Berbiche D, Lamarre D, Corneille L, Prud’homme L et al. Impact of collaborative and multidisciplinary care on management of hypertension in chronic kidney disease outpatients. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2011; 2(2):79–87

- 87.

- Schofield RF, Amodeo M. Interdisciplinary teams in health care and human services settings: are they effective? Health and Social Work. 1999; 24(3):210–219 [PubMed: 10505282]

- 88.

- Shyu YI, Liang J, Wu CC, Cheng HS, Chen MC. An interdisciplinary intervention for older Taiwanese patients after surgery for hip fracture improves health-related quality of life. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010; 11:225 [PMC free article: PMC3161401] [PubMed: 20920220]

- 89.

- Shyu YI, Liang J, Wu CC, Su JY, Cheng HS, Chou SW et al. Two-year effects of interdisciplinary intervention for hip fracture in older Taiwanese. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010; 58(6):1081–1089 [PubMed: 20722845]

- 90.

- Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Lundstrom M, Englund U, Borssen B, Svensson O et al. A multidisciplinary, multifactorial intervention program reduces postoperative falls and injuries after femoral neck fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2007; 18(2):167–175 [PMC free article: PMC1766476] [PubMed: 17061151]

- 91.

- Tan SB, Williams AF, Kelly D. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary interventions to improve the quality of life for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014; 51(1):166–174 [PubMed: 23611510]

- 92.

- Trochu JN, Baleynaud S, Mialet G. Efficacy of a multidisciplinary management of chronic heart failure patients: one year results of a multicentre randomized trial in French medical practice. European Heart Journal. 2003; 24(abstr suppl):484

- 93.

- Tseng MY, Shyu YI, Liang J. Functional recovery of older hip-fracture patients after interdisciplinary intervention follows three distinct trajectories. Gerontologist. 2012; 52(6):833–842 [PubMed: 22555886]

- 94.

- van den Hout WB, Tijhuis GJ, Hazes JM, Breedveld FC, Vliet Vlieland TP. Cost effectiveness and cost utility analysis of multidisciplinary care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised comparison of clinical nurse specialist care, inpatient team care, and day patient team care. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2003; 62(4):308–315 [PMC free article: PMC1754484] [PubMed: 12634227]

- 95.

- van der Marck MA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Overeem S, Munneke M, Guttman M. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Movement Disorders. 2013; 28(5):605–611 [PubMed: 23165981]

- 96.

- Vliet Vlieland TP, Hazes JM. Efficacy of multidisciplinary team care programs in rheumatoid arthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1997; 27(2):110–122 [PubMed: 9355209]

- 97.

- Vliet Vlieland TP, Zwinderman AH, Vandenbroucke JP, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. A randomized clinical trial of in-patient multidisciplinary treatment versus routine out-patient care in active rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1996; 35(5):475–482 [PubMed: 8646440]

- 98.

- Wang SM, Hsiao LC, Ting IW, Yu TM, Liang CC, Kuo HL et al. Multidisciplinary care in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2015; 26(8):640–645 [PubMed: 26186813]

- 99.

- White V, Currey J, Botti M. Multidisciplinary team developed and implemented protocols to assist mechanical ventilation weaning: a systematic review of literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2011; 8(1):51–59 [PubMed: 20819199]

- 100.

- Wierzchowiecki M, Poprawski K, Nowicka A, Kandziora M, Piatkowska A, Jankowiak M et al. A new programme of multidisciplinary care for patients with heart failure in Poznan: one-year follow-up. Kardiologia Polska. 2006; 64(10):1063–2 [PubMed: 17089238]

- 101.

- Wild D, Nawaz H, Chan W, Katz DL. Effects of interdisciplinary rounds on length of stay in a telemetry unit. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2004; 10(1):63–69 [PubMed: 15018343]

- 102.

- Williams ME, Williams TF, Zimmer JG, Hall WJ, Podgorski CA. How does the team approach to outpatient geriatric evaluation compare with traditional care: a report of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1987; 35(12):1071–1078 [PubMed: 3119693]

- 103.

- Wolfs CA, Dirksen CD, Kessels A, Severens JL, Verhey FR. Economic evaluation of an integrated diagnostic approach for psychogeriatric patients: results of a randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009; 66(3):313–323 [PubMed: 19255381]

- 104.

- Yagura H, Miyai I, Suzuki T, Yanagihara T. Patients with severe stroke benefit most by interdisciplinary rehabilitation team approach. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2005; 20(4):258–263 [PubMed: 16123546]

- 105.

- Yoo JW, Kim S, Seol H, Kim SJ, Yang JM, Ryu WS et al. Effects of an internal medicine floor interdisciplinary team on hospital and clinical outcomes of seniors with acute medical illness. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. 2013; 13(4):942–948 [PubMed: 23441847]

- 106.

- Zwijsen SA, Smalbrugge M, Eefsting JA, Twisk JWR, Gerritsen DL, Pot AM et al. Coming to grips with challenging behavior: a cluster randomized controlled trial on the effects of a multidisciplinary care program for challenging behavior in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014; 15(7):531–10 [PubMed: 24878214]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 7Review protocol: Multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs)

| Review question | MDT |

|---|---|

| Guideline condition and its definition | Acute Medical Emergencies. |

| Objectives | Good communication and coordination of care between all health and social care staff involved in patient care during a hospital stay is considered vital to ensure that it is delivered optimally. This should ensure the whole process is performed efficiently with minimal delays and repetition. Multidisciplinary meeting (MDTs) is a mechanism by which this information is shared between various professionals involved in the patient’s care. MDTs could ensure that all the relevant information from each professional is captured and shared. This could have a positive effect on patient care. |

| Review population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME in hospital. |

| Adults and young people (16 years and over). | |

| Line of therapy not an inclusion criterion. | |

|

Interventions and comparators: generic/class; specific/drug (All interventions will be compared with each other, unless otherwise stated) |

MDT process; physicians, nurses, allied health professionals and, where appropriate, primary care and social work as determined by patient need. No MDT process; no MDT (best practice). |

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Unit of randomization | Patient. |

| Crossover study | Permitted. |

| Minimum duration of study | Not defined. |

| Other exclusions |

Elective care (including cancer). Trauma. Community hospital MDTs. Outpatients. |

| Subgroup analyses if there is heterogeneity |

|

| Search criteria |

Databases: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library. Date limits for search: 1990. Language: English. |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

C.1. Multidisciplinary care/intervention versus no multidisciplinary care/intervention

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (659K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No relevant economic evidence was identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 8Clinical evidence profile: Multidisciplinary care/intervention versus no multidisciplinary care/intervention

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | MDT process | No MDT process | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (all-cause) | ||||||||||||

| 7 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | very serious3 | None |

83/758 (12.6%) | 7.3% | RR 1.03 (0.78 to 1.37) | 3 more per 1000 (from 23 fewer to 39 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Length of hospital stay (days) - (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 7 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None | 743 | 722 | - | MD 1.22 lower (2.33 to 0.12 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Re-admissions for CHF | ||||||||||||

| 3 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious4 | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None |

25/225 (11.1%) | 25% | RR 0.25 (0.05 to 1.23) | 188 fewer per 1000 (from 237 fewer to 58 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Quality of life (Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire) (Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None | 67 | 59 | - | MD 10.8 higher (4.29 to 17.31 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Re-admissions (all-cause) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | serious3 | None |

87/238 (36.6%) | 45.7% | RR 0.64 (0.52 to 0.79) | 165 fewer per 1000 (from 96 fewer to 219 fewer) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Re-admissions (all-cause) (Patients with major depression) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | very serious3 | None |

13/33 (39.4%) | 29% | RR 1.36 (0.68 to 2.72) | 104 more per 1000 (from 93 fewer to 499 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Re-admissions (all-cause) (Patients with HF) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None |

74/205 (36.1%) | 56.4% | RR 0.59 (0.47 to 0.73) | 231 fewer per 1000 (from 152 fewer to 299 fewer) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias

- 2

All studies compare multidisciplinary care/intervention with no multidisciplinary care/intervention, they do not compare multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) as specified in the protocol.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID point, and downgraded by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed 2 MID points.

- 4

Downgraded by 1 or 2 increments because heterogeneity, I2=63%, unexplained by sub-group analysis.

Table 9Clinical evidence profile: Multidisciplinary ward rounds versus no multidisciplinary ward rounds

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Multidisciplinary ward rounds | Traditional ward rounds | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality - Multidisciplinary ward rounds versus no multidisciplinary ward rounds | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | None |

10/567 (1.8%) | 1.9% | RR 0.94 (0.4 to 2.25) | 1 fewer per 1000 (from 11 fewer to 24 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Length of hospital stay (days) - Multidisciplinary ward rounds versus no multidisciplinary ward rounds (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious inconsistency2 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 609 | 577 | - | MD 0.10 lower (1.02 lower to 0.82higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID point, and downgraded by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed 2 MID points.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 or 2 increments because heterogeneity, I2=60%, unexplained by sub-group analysis.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 10Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Ahmed 20022 | This is a review/commentary on a systematic review (McAlister 2001). Patients not in hospital. MDT not in title of McAlister 2001 |

| Anon 20131 | Not MDT in title |

| Austin 20093 | Not ward/in-hospital MDT |

| Bearne 20164 | Systematic review. Two references ordered |

| Britton 20005 | Cochrane review withdrawn. This review is replaced by 2 separate protocols: “Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised patients” and “Multidisciplinary Team Interventions for the management of delirium in hospitalized patients” |

| Callens 20066 | Article |

| Cameron 20137 | Incorrect setting. Older people who were frail in the community. |

| CAO 20168 | Abstract only |

| Caplan 20049 | Incorrect interventions. The study compared comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the elderly from the emergency department to usual care |

| Capomolla 200210 | Outpatients -patients discharged by a HF unit were randomised to usual care and HF management programme |

| Carey 201011 | Review. Checked references. |

| Chan 201112 | Not AME patients. Multi-disciplinary primary care for mothers living in areas of socio-economic deprivation. |

| Chock 201313 | Incorrect population. Advanced cancer patients scheduled to receive radiation therapy. (elective care excluded in protocol) |

| Clark 201314 | Not AME. Patients undergoing radiation therapy for advanced cancer |

| Collard 198517 | Not MDT |

| Connolly 201418 | Abstract |

| Copperman 199719 | Incorrect population and setting. Adolescents with cardiovascular risk factors in home/community. |

| Der 200922 | Article |

| Ellrodt 200723 | Report of the performance of a community teaching hospital in ‘Get with the guidelines’ programme using multi-disciplinary rounds. |

| Fakih 200824 | Incorrect study design. Quasi experimental study. |

| Flikweert 201425 | Incorrect study design. Clinical trial in which the data of the intervention group was collected prospectively and compared with a historical control group. |

| Gade 200826 | Not guideline condition. Not review population. Palliative care not AME |

| Garrubba 200927 | Systematic review- checked for relevant references. |

| Gray 201028 | Incorrect population. Patients with chronic diseases. |

| Gums 199929 | Incorrect setting- community hospital. |

| Hays 200631 | Inappropriate comparison. Multidisciplinary ward rounds every day versus multidisciplinary ward rounds once a week |

| Hendriks 200532 | Study protocol |

| Hendry 201333 | Not AME patients. Children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and inflammatory joint disease affecting the foot/ankle |

| Hickman 201534 | Systematic review. One reference ordered. |

| Holland 200535 | Systematic review. Checked references |

| HUNLEY 201636 | Abstract only |

| Jaarsma 199937 | Letter to the editor |

| Johansson 201039 | Systematic review but no actual outcome data; included RCTs assessed individually |

| Johnson 200940 | Incorrect study design. Before-After study |

| Kasper 2002 | Not correct population, outpatients. |

| Ke 201341 | SR does not give enough information on the studies and their quality to be taken as a whole; individual RCTs assessed |

| Kim 2016A42 | Not in English |

| Kominski 200143 | Incorrect setting. Setting is home/community. Intervention begins after patient has been discharged from the hospital. |

| Koshman 200744 | Design of an RCT. |

| Lamb 201145 | Systematic review. References checked |

| Langhorne 201146 | Systematic review: literature search not sufficiently rigorous. SR; included studies checked |

| Lapid 200748 | Incorrect population. Advanced cancer patients who required radiation therapy. (elective care excluded in protocol) |

| Lapid 201347 | Incorrect population. Advanced cancer patients scheduled to receive radiation therapy (elective care excluded in protocol) |

| Lemstra 200249 | Incorrect population and setting. Migraine patients in a non-clinical setting. |

| Leventhal 201150 | Not ward/in-hospital MDT; only home visits after discharge |

| Licata 201351 | Incorrect study design. Before-after study |

| Lincoln 200452 | Intervention in community, not ward/in-hospital MDT |

| Lu 201453 | Incorrect interventions. Not MDT versus no MDT |

| McCorkle 201557 | Inappropriate population- patients with late stage cancer |

| Markle-reid 201054 | Not review population. Not AME in hospital. Interdisciplinary team approach to falls prevention for older home care patients ‘at risk’ for falling. |

| Marra 201255 | Incorrect population and setting. Patients with knee pain recruited from local community pharmacies. |

| Mattila 200356 | Incorrect population and setting. Middle aged hypertensives in rehabilitation centres. |

| Mcmurray 199660 | Only title with grant offered. No abstract or full text of the trial available. |

| Melin 199561 | Incorrect setting- elderly patients in home care |

| Metzelthin 201362 | Incorrect population and setting. Frail older people in the community. |

| Mitchell 200863 | Systematic review. Multidisciplinary care of stroke patients in a primary care setting. |

| Momsen 201264 | Systematic review is not relevant to review question or unclear PICO. Most included studies not AME; potential studies assessed separately. Not guideline condition |

| Mudge 201365 | Not RCT. This is a concurrent controlled trial (not randomised). |

| Naglie 200266 | Not AME. Elderly people with hip fracture. |

| Nazir 201370 | Systematic review. Incorrect settings- nursing homes/or residential care settings. |

| Ng 200971 | Cochrane review- No RCTs identified. Not AME- Patients with motor neuron disease (MND) |

| Nikolaus 199973 | Incorrect setting- older patients homes |

| Nikolaus 200372 | Incorrect setting- older people homes |

| O’leary 201174 | Not RCT. Retrospective medical review of 2similar teaching service units which were randomly selected for the intervention (Interdisciplinary rounds) and control units. |

| Pannick 201575 | Systematic review- checked for relevant references |

| Peeters 200776 | Incorrect population and setting. Older people with a high risk of falling in residential homes or in the community |

| Pieper 201677 | Incorrect setting- outpatients. Study assessed the effectiveness of multicomponent intervention in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. |

| Pillay 201678 | Systematic review. Incorrect setting- oncology setting |

| Pitkala 200679 | Incorrect intervention. Multicomponent geriatric intervention (including comprehensive assessment, physiotherapy, additional supplements/treatments, comprehensive discharge planning) for delirium patients. |

| Pope 201180 | Community hospital MDTs |

| Rabow 200481 | Not guideline condition. Palliative care not AME |

| Reuben 199582 | No MDT. Incorrect interventions |

| Rummans 200685 | Incorrect population. Advanced cancer patients scheduled to receive radiation therapy. (elective care excluded in protocol) |

| Santschi 201186 | Not AME. Management of hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. Incorrect setting-out-patients. |

| Schofield 199987 | Systematic review. SR but no eligible studies |

| Shyu 201088 | Not AME patients. Older patients with hip fracture. |

| Shyu 201089 | Not AME patients. Older patients with hip fracture. |

| Stenvall 200790 | Not AME patients. Older patients with femoral neck fracture. |

| Tan 201491 | Systematic review. Incorrect population and setting- People with Parkinson’s Disease in the community |

| Trochu 200392 | Conference abstract only. |

| Tseng 201293 | Not AME patients. Older patients with hip fracture. |

| Van den hout 200394 | Not guideline condition. Outpatients, not AME in hospital |

| Van der marck 201395 | Not AME patients. Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. |

| Vlietvlieland 199697 | Not AME. Patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Vlietvlieland 199796 | Not AME. Patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Wang 201598 | Systematic review. Multidisciplinary care in patients with chronic kidney disease. Checked for relevant references. |

| White 201199 | Systematic review: study designs inappropriate. Included studies are not RCTs |

| Wierzchowiecki 2006100 | Community hospital MDT |

| Wild 2004101 | Interdisciplinary rounds in a community hospital |

| Williams 1987102 | Not guideline condition. Community hospital MDTs |

| Wolfs 2009103 | Incorrect setting as ambulatory |

| Yagura 2005104 | Incorrect study design. Patients allocated based on bed availability. |

| Yoo 2013105 | Incorrect study design. Not RCT. |

| Zwijsen 2014106 | Incorrect population and setting. Patients with dementia in nursing homes. |

Appendix H. Excluded economic studies

No relevant economic studies were identified.

- Multidisciplinary team meetings - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: ...Multidisciplinary team meetings - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...