NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details31. Enhanced in-patient access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy

31.1. Introduction

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy are an important component in the recovery from acute illness, particularly in chest disease, injurious falls, stroke and prolonged admission or with pre-existing frailty. More intense therapy would be expected to lead to shorter hospital stays and quicker recovery from immobility caused by illness. Likewise, the risk of physical deterioration from lack of access to therapies over a weekend would be expected to extend hospital stay and increase comorbidities.

Currently, 7-day services are regularly expected in specialist services such as respiratory units, and trauma units, but less so on general medical wards.

31.2. Review question: Is enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy for hospital patients clinically and cost effective?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

31.3. Clinical evidence

We searched for randomised controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of enhanced (7-day a week) inpatient access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy versus standard 5-day inpatient access for patients hospitalised with an acute medical emergency.

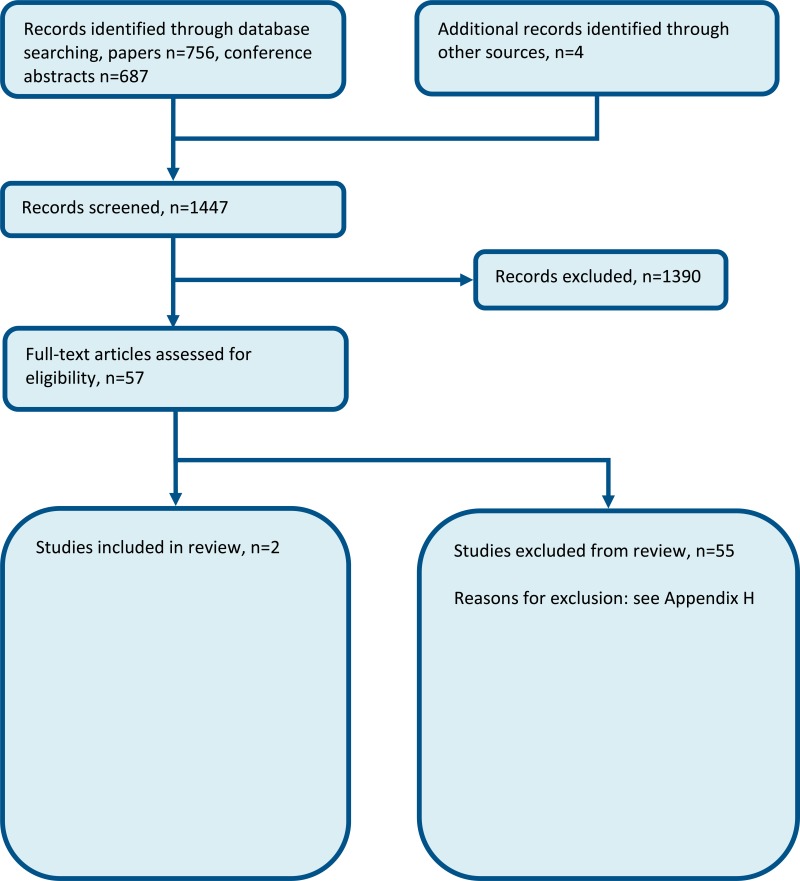

Two RCTs (3 papers) were included in the review;23,31,50 these are summarised in Table 2 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 3). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Clinical evidence profile: enhanced versus standard access to physio- and/or occupational therapy.

Narrative findings

Length of stay

English 201523 reported a median length of stay of 45.0 days (IQR ±38.0; range 14 to 460) for the 7 day a week therapy intervention group and a median of 55.0 days (IQR ±49.0; range 14 to 240) for the usual care therapy.

Said 201250 reported a median rehabilitation stay of 16 days (IQR 11-27.5; range 8 to 49) for the enhanced access intervention group compared to a median of 15 days (IQR 13.0-22.5; range 8 to 41) for the control group.

Quality of life

English 201523 reported the median overall score of the Australian Quality of Life scale to be 0.2 (IQR ±0.40; range −0.2 to 1.0) for the intervention group and 0.24 (IQR ±0.47; range −0.2 to 1.0) for the usual care group.

31.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

New cost-effectiveness analysis

An original cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted for this topic. This is summarised in the economic evidence profile below (Table 4) and is detailed in Chapter 41.

Table 4

Economic evidence profile: Extended access to therapy.

31.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

Older people

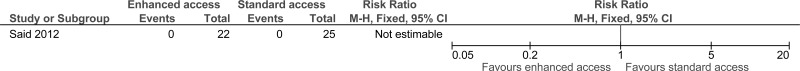

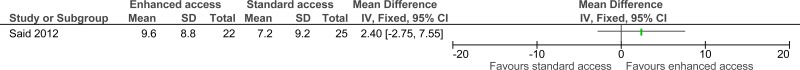

- One study comprising 47 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy for improving outcomes in secondary care in older people recovering from an AME. The evidence suggested that enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy may provide benefits in reduced mortality at 3 months (1 study, very low quality) and quality of life (1 study, moderate quality). However, there was no effect on readmission (1 study, high quality), adverse events expressed as non-injurious falls (1 study, low quality) and mortality at discharge (1 study, high quality).

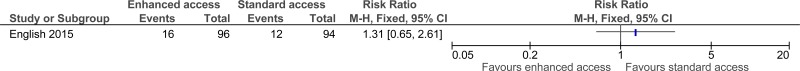

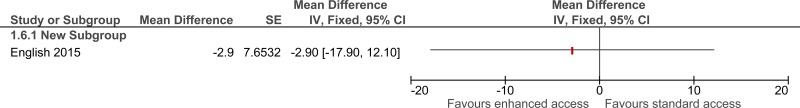

Stroke

- One study comprising 283 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy for improving outcomes in secondary care in adults and young people who are recovering from a stroke. The evidence suggested that enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy had more adverse events - falls and other unspecified events (1 study, low quality) but did provide benefit in a reduced length of rehabilitation (1 study, high quality).

Economic

- Two original cost-utility analyses (cohort model and simulation model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people recovering from an acute medical emergency (AME) on the general medical wards was dominant, increasing QALYs and cost saving (cost difference: -£90 per patient). This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One original cost-minimisation analysis (cohort model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people presenting in the Emergency Department with a suspected AME was cost increasing (cost difference: +£0.72 per patient) . This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One original cost-utility analysis (simulation model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people recovering from an AME on the general medical wards was dominated by standard access. This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

31.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendation | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes | The guideline committee chose the outcomes of mortality, patient and/or carer satisfaction, quality of life, length of stay and avoidable adverse events as critical outcomes. Discharge to normal place of residency, readmission, time to mobilisation and delayed transfers of care were selected as important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

Two RCTs were identified that compared enhanced therapy access to physiotherapy to standard access in 2 populations (stroke patients and older people). They were analysed separately. Older People One study comprising 47 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy in older people. The evidence suggested that enhanced access to physiotherapy may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (at 3 months) and quality of life (change in mobility from baseline). However, there was no effect on readmission, adverse events (non- injurious falls) and mortality at discharge. Stroke patients One study comprising 283 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy in stroke patients. The evidence suggested those with enhanced access to physiotherapy had more adverse events (falls and other unspecific events) but it did provide a benefit in a reduced length of rehabilitation stay. The committee considered that the reduced length of stay may coincide with an improved quality of life (for example, by enhancing mobility), but this was not measured by the study. There was some evidence to suggest more adverse events, falls in particular, in the enhanced access group. The committee noted that this might be a result of increasing rehabilitation and mobility resulting in an increased number of falls. No evidence was found for discharge to normal place of residency, patient and/or carer satisfaction, time to mobilisation and delayed transfers of care. The committee discussed that physiotherapists and occupational therapists serve 2 major functions; they can potentially avert or reduce the risk of complications (for example, DVTs, pressure ulcers, postural instability) but may also increase the speed with which patients can be discharged as early mobilisation improves function. Assessment by a qualified therapist is required to develop a treatment plan in order to mobilise patients early, reduce or avert secondary complications and shorten their length of stay. The committee felt that early mobilisation is crucial but noted that if patients are admitted on a Friday for example, their treatment is delayed by 2 days if no qualified therapist can assess the patient before Monday. The committee were aware that qualified therapists are also required to facilitate patient discharge. The committee felt that if a hospital already provided a 7-day service, physiotherapy and occupational therapy assessment should be provided as part of this service to facilitate discharge and improve patient flow. It also facilitates a more equitable NHS service to patients irrespective of the day of their admission. The committee considered that, once the management plan had been formed by a qualified therapist, it could be implemented by assistants or nurses, which may reduce the costs of this intervention. The committee highlighted that the enhanced service should be targeted for patients in need of therapy and may be unnecessary for those already mobile or bedbound. The committee decided to make a strong recommendation because there was high quality evidence for a reduction in length of stay and moderate/low quality evidence for benefits to mortality at 3 months and quality of life. There was no evidence for occupational therapy but the committee considered that the evidence for physiotherapy was likely to be applicable to occupational therapy as well. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

No economic studies were identified. The clinical review showed reduced length of stay and an increase in quality of life as well as a slight improvement in survival, which supports a recommendation of enhanced access to physiotherapy in terms of clinical effectiveness. The committee noted that the cost of the intervention could be reduced if conducted partly by a therapy assistant or as part of an exercise class where multiple people are being treated together. They also noted that physiotherapy and occupational therapy are usually delivered by a team of staff with mixed skills and therefore, it is not appropriate to evaluate the two separately. New cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted for 2 areas of enhancing therapy access, the ED and medical wards. A cohort model was built to assess the costeffectiveness of enhanced therapy access. A hospital simulation model was also built to explore how the intervention’s impact on hospital flow could affect its cost-effectiveness. Both models used inputs from bespoke data analysis, national data and treatment effects (primarily length of stay reduction and modest reductions in adverse events) that were informed by the above review but elicited from the committee members. The full model write up can be found in Chapter 41. Extended access to physiotherapy/occupational therapy in the emergency department The models compared extended access to therapy in the ED versus standard staffing hours. Extended access involves additional availability of physiotherapists and occupational therapists in the ED, using additional resources in terms of staff time at an incremental cost to normal care. The cohort model found that extended access in the ED was slightly cost increasing in the base case analysis with assumed no effect on quality of life, hence no gain in quality-adjusted life-years. With less conservative assumptions about the effect of the extended access on admission, it was cost saving. The committee noted that extended access is a costly intervention with a limited amount of time to impact on the patients. The main impact of extended access in the ED is likely to be on hospital flow, not fully taken into account by the cohort model. In the hospital simulation model, extended access in ED was cost increasing with no gain in quality-adjusted life-years. There were decreases in admissions, but only a small impact on four-hour breeches and hospital length of stay. However, there was no impact on other important outcomes, such as number of medical outliers and mortality. The committee could not conclude that extended access in the ED would be cost effective. It might have a significantly positive impact on hospital flow and patient outcomes at a cost-effective level in some hospitals operating at sub-optimal levels of efficiency within the emergency department Extended access to physiotherapy/occupational therapy in the general medical wards Both models compared daily therapy on medical wards with weekday access only. Extended access involves additional availability of physiotherapists and occupational therapists in the general medical wards, using additional resources in terms of staff time at an incremental cost to normal care. In both models, extended access in the wards was dominant, cost saving with a gain in quality-adjusted life-years. These findings are similar to those found in a randomised trial of rehabilitation at the weekend in Australia, albeit in a mixed medical/surgical population14. The committee also noted the impact on important outcomes linked to hospital flow. There were decreases in four-hour breeches and medical outliers and a modest reduction in mortality. The committee concluded that extended access on medical wards could have a significantly positive impact on hospital flow and patient outcomes at a costeffective level in hospitals. This result was robust to sensitivity analysis. Conclusions The committee concluded that extended access to therapy on medical wards was likely to be cost saving. When assessing the uncertainty in these costs, the committee also considered the increase in quality of life and improved mortality, and believed that extended access would remain cost effective even if there was a small increase in cost. The committee therefore agreed that extended access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy on medical wards was likely to be cost effective. To implement this recommendation, some Trusts will need to increase the provision of physiotherapy and occupational therapy services. This cost should be offset by cost savings from reduced length of stay. |

| Quality of evidence |

Two RCTs were identified by the search that compared enhanced versus standard access to therapy in a relevant AME population. One study, including older patients had a small sample size. The evidence was graded high for mortality (at discharge) and readmission. The other outcomes were graded moderate to very low quality due to imprecision and risk of bias. The evidence for stroke patients was graded as high quality for length of rehabilitation stay and low quality for adverse events due to serious imprecision. The committee felt, however, that the evidence identified in stroke patients should be cautiously extrapolated to other populations, given that the needs of these patients were quite specific. All evidence identified was for physiotherapy access only but the committee considered that physiotherapy and occupational therapy services are closely linked with the former concerned with physical function and the latter focused on the application of that function. These services becoming increasingly integrated with staff frequently having a mixture of both sets of skills and the committee wanted to reflect this in its recommendation. The original health economic modelling was assessed to be directly applicable but still had potentially serious limitations due to the treatment effects being based on expert opinion, albeit conservative and informed by the guideline’s systematic review. |

| Other considerations |

The committee were aware of other NICE guidelines, for example, stroke (CG68, rec 1.7.1.1), hip fracture (CG124, rec 1.7.1 and 1.7.2) and venous thromboembolism (CG92, rec 1.2.2.),39–41 that recommend early mobilisation of patients. The committee discussed the advantages of early mobilisation to reduce morbidity and length of stay of patients with an acute medical emergency. Providing increased access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy would facilitate this and hence the committee made a strong positive recommendation. Bed rest was historically used therapeutically in the management of many chronic illnesses in patients admitted to hospitals. Unfortunately, the deleterious consequences of immobility predispose patients, particularly the elderly (as they have less functional reserve), to significant functional decline and reduced quality of life. Prolonged inactivity reduces the physiologic reserve of most organ systems, particularly the musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary systems. Consequently, muscle weakness, contracture formation, postural hypotension and thrombogenic events are common in bed-bound patients. Fortunately, contemporary studies have dispelled the myth that inactivity fosters healing and have suggested techniques that may prevent immobility-induced dysfunction and ensure beneficial outcome particularly in the fragile and aging populations. |

References

- 1.

- A trial to evaluate an extended rehabilitation service for stroke patients. Health Technology Assessment, 2012. Available from: http://www

.nets.nihr .ac.uk/__data/assets /pdf_file/0007/81664/PRO-10-37-01.pdf - 2.

- Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Walker TA, Bartle J, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ et al. Group physical therapy for veterans with knee osteoarthritis: study design and methodology. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013; 34(2):296–304 [PMC free article: PMC8443150] [PubMed: 23279750]

- 3.

- Archer KR. Determinants of referral to physical therapy: influence of patient work status and surgeon efficacy beliefs Johns Hopkins University; 2008.

- 4.

- Arnold SM, Dinkins M, Mooney LH, Freeman WD, Rawal B, Heckman MG et al. Very early mobilization in stroke patients treated with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015; 24(6):1168–1173 [PubMed: 25869770]

- 5.

- Artz N, Dixon S, Wylde V, Beswick A, Blom A, Gooberman-Hill R. Physiotherapy provision following discharge after total hip and total knee replacement: a survey of current practice at high-volume NHS hospitals in England and Wales. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013; 11(1):31–38 [PubMed: 22778023]

- 6.

- Babu AS, Noone MS, Haneef M, Samuel P. The effects of ‘on-call/out of hours’ physical therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010; 24(9):802–809 [PubMed: 20543018]

- 7.

- Baggaley K, Benn S, Eastwood M, Robinson K, Shaw K, Wirtz A et al. Opening Pandora’s box: describing the scope of occupational therapy practice in a community health service in Victoria... Occupational Therapy Australia, 24th National Conference and Exhibition, 29 June - 1 July 2011. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58:28

- 8.

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. a journal of cerebral circulation 2008; 39(2):390–396 [PubMed: 18174489]

- 9.

- Bethel J. The role of the physiotherapist practitioner in emergency departments: a critical appraisal. Emergency Nurse. 2005; 13(2):26–31 [PubMed: 15912710]

- 10.

- Borrows A, Holland R. Independent living centre occupational therapy (OT) versus routine community OT. International Journal of Therapy & Rehabilitation. 2013; 20(4):187–194

- 11.

- Brandstater ME. Physical medicine and rehabilitation and acute inpatient rehabilitation. PM and R. 2011; 3(12):1079–1082 [PubMed: 22192318]

- 12.

- Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Taylor NF. Are weekend inpatient rehabilitation services value for money? An economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial with a 30 day follow up. BMC Medicine. 2014; 12(2):89 [PMC free article: PMC4053313] [PubMed: 24885811]

- 13.

- Brusco NK, Shields N, Taylor NF, Paratz J. A Saturday physiotherapy service may decrease length of stay in patients undergoing rehabilitation in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2007; 53(2):75–81 [PubMed: 17535142]

- 14.

- Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Taylor NF. Is cost effectiveness sustained after weekend inpatient rehabilitation? 12 month follow up from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2015; 15:165 [PMC free article: PMC4438580] [PubMed: 25927870]

- 15.

- Caldwell KE, Hughes L, Sturt R. Audit to establish the impact of staffing levels on the quality and intensity of physiotherapy treatment of stroke patients against Royal College of Physicians (RCP) guidelines. International Journal of Stroke. 2009; 4:28

- 16.

- Campbell L, Bunston R, Colangelo S, Kim D, Nargi J, Brooks D et al. The provision of weekend physical therapy services in university-affiliated hospitals with an intensive care unit in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2009; 61:54

- 17.

- Campbell L, Bunston R, Colangelo S, Kim D, Nargi J, Hill K et al. The provision of weekend physiotherapy services in tertiary-care hospitals in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010; 62(4):347–354 [PMC free article: PMC2958077] [PubMed: 21886374]

- 18.

- Connelly RS, Thomas PW. Solving the riddle of inpatient rehabilitation coverage. Healthcare Financial Management. 2007; 61(3):98–104 [PubMed: 19097629]

- 19.

- Connolly B, Salisbury L, O’Neill B, Geneen L, Douiri A, Grocott Michael PW et al. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; Issue 6:CD008632. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008632.pub2 [PMC free article: PMC6517154] [PubMed: 26098746] [CrossRef]

- 20.

- Curtis A, Ainsworth H, Anderson J, Osman L. Functional outcome measures on discharge from intensive care: an evaluation of an extended seven day working pilot. Intensive Care Medicine. 2011; 37:S271

- 21.

- Deane KHO. Randomised controlled trials: part 2, reporting. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006; 69(6):248–254

- 22.

- Duncan C, Hudson M, Heck C. The impact of increased weekend physiotherapy service provision in critical care: a mixed methods study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2015; 31(8):547–555 [PubMed: 26467461]

- 23.

- English C, Bernhardt J, Crotty M, Esterman A, Segal L, Hillier S. Circuit class therapy or seven-day week therapy for increasing rehabilitation intensity of therapy after stroke (CIRCIT): a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2015; 10(4):594–602 [PubMed: 25790018]

- 24.

- English C, Shields N, Brusco NK, Taylor NF, Watts JJ, Peiris C et al. Additional weekend therapy may reduce length of rehabilitation stay after stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2016; 62(3):124–129 [PubMed: 27320831]

- 25.

- Gawned S, Lindfield H, Cooke EV. A ‘7 day service’ for therapies: providing an expanded weekend stroke service. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013; 35:771

- 26.

- Gawned SL, Lindfield HE, Eddison J, Cooke EV. Seven day stroke therapy services - developing a weekend service on the hyperacute stroke unit. International Journal of Stroke. 2013; 8:63

- 27.

- Gräsel E, Biehler J, Schmidt R, Schupp W. Intensification of the transition between inpatient neurological rehabilitation and home care of stroke patients. Controlled clinical trial with follow-up assessment six months after discharge. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005; 19(7):725–736 [PubMed: 16250191]

- 28.

- Gurr B, Dendle J. Assessment of stroke survivors on an inpatient rehabilitation unit. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing.: MA Healthcare Limited. 2015; 11(4):179–184

- 29.

- Haines TP, O’Brien L, Mitchell D, Bowles K-A, Haas R, Markham D et al. Study protocol for two randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness and safety of current weekend allied health services and a new stakeholder-driven model for acute medical/surgical patients versus no weekend allied health services. Trials. 2015; 16(1):133 [PMC free article: PMC4403707] [PubMed: 25873250]

- 30.

- Hill K, Brooks D. A description of weekend physiotherapy services in three tertiary hospitals in the greater Toronto area. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010; 62(2):155–162 [PMC free article: PMC2871025] [PubMed: 21359048]

- 31.

- Hillier S, English C, Crotty M, Segal L, Bernhardt J, Esterman A. Circuit class or seven-day therapy for increasing intensity of rehabilitation after stroke: protocol of the CIRCIT trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2011; 6(6):560–565 [PubMed: 22111802]

- 32.

- Kalsi S, Allum L, Thomas A, Patel M, McDonald H. An audit and observation of current practice: the impact of physiotherapy seven-day working in intensive care. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2014; 15:(Suppl 1):S43–S44

- 33.

- Kersten P, McPherson K, Lattimer V, George S, Breton A, Ellis B. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice - who is doing what and why? Physiotherapy. 2007; 93(4):235–242

- 34.

- Kolber MJ, Hanney WJ, Lamb BM, Trukman B. Does physical therapy visit frequency influence acute care length of stay following knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2013; 29(1):25–29

- 35.

- Lay J, O’Shea H, Loughborough B, Potter J, Guyler PC, O’Brien A. 7 Day-a-week rehabilitation in a united kingdom district general hospital stroke unit reduces patient length of stay and improves patient satisfaction with the stroke service. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010; 29:337

- 36.

- Lim ECW, Liu J, Yeung MTL, Wong WP. After-hour physiotherapy services in a tertiary general hospital. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2008; 24(6):423–429 [PubMed: 19117233]

- 37.

- Maidment ZL, Hordacre BG, Barr CJ. Effect of weekend physiotherapy provision on physiotherapy and hospital length of stay after total knee and total hip replacement. Australian Health Review. 2014; 38(3):265–270 [PubMed: 24804607]

- 38.

- McClellan CM, Greenwood R, Benger JR. Effect of an extended scope physiotherapy service on patient satisfaction and the outcome of soft tissue injuries in an adult emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006; 23(5):384–387 [PMC free article: PMC2564090] [PubMed: 16627842]

- 39.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Venous thromoembolism: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) inpatients admitted to hospital. NICE clinical guideline 92. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. Available from: http://www

.nice.org.uk/CG92 - 40.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. The management of hip fracture in adults. NICE clinical guideline 124. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2011. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG124 - 41.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). NICE clinical guideline 68. London. Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG68 [PubMed: 21698846] - 42.

- Ottensmeyer CA, Chattha S, Jayawardena S, McBoyle K, Wrong C, Ellerton C et al. Weekend physiotherapy practice in community hospitals in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2012; 64(2):178–187 [PMC free article: PMC3321989] [PubMed: 23449882]

- 43.

- Paradza B. 7-Day physiotherapy pathway reduces hospitalisation following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) when compared to 5-day pathway-a service evaluation study. Physiotherapy. 2011; 97:eS963

- 44.

- Peiris C, Shields N, Taylor NF. Extra physical therapy and occupational therapy increased physical activity levels in orthopedic rehabilitation: randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93(10):E14 [PubMed: 22446517]

- 45.

- Peiris CL, Shields N, Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Taylor NF. Additional Saturday rehabilitation improves functional independence and quality of life and reduces length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Medicine. 2013; 11:198 [PMC free article: PMC3844491] [PubMed: 24228854]

- 46.

- Peiris CL, Taylor NF, Shields N. Additional Saturday allied health services increase habitual physical activity among patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for lower limb orthopedic conditions: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93(8):1365–1370 [PubMed: 22446517]

- 47.

- Reid A, Hills L. A pilot study to assess the impact of a seven-day therapy service on a stroke unit. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010; 29:151–152

- 48.

- Roberts L. Improving quality, service delivery and patient experience in a musculoskeletal service. Manual Therapy. 2013; 18(1):77–82 [PubMed: 22609270]

- 49.

- Robinson A, Lord-Vince H, Williams R. The need for a 7-day therapy service on an emergency assessment unit. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 77(1):19–23

- 50.

- Said CM, Morris ME, Woodward M, Churilov L, Bernhardt J. Enhancing physical activity in older adults receiving hospital based rehabilitation: a phase II feasibility study. BMC Geriatrics. 2012; 12:26 [PMC free article: PMC3502428] [PubMed: 22676723]

- 51.

- Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL, Walsh TS. The development and feasibility of a ward-based physiotherapy and nutritional rehabilitation package for people experiencing critical illness. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010; 24(6):489–500 [PubMed: 20410151]

- 52.

- Saxon RL, Gray MA, Ioprescu F. Extended roles for allied health professionals: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2014; 7:479–488 [PMC free article: PMC4206389] [PubMed: 25342909]

- 53.

- Scrivener K, Jones T, Schurr K, Graham PL, Dean CM. After-hours or weekend rehabilitation improves outcomes and increases physical activity but does not affect length of stay: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2015; 61(2):61–67 [PubMed: 25801362]

- 54.

- Shaw KD, Taylor NF, Brusco NK. Physiotherapy services provided outside of business hours in Australian hospitals: a national survey. Physiotherapy Research International. 2013; 18(2):115–123 [PubMed: 23038214]

- 55.

- Silva JM, Rotta BP, Padovani C, Ramos M, Fu C, Tanaka C. 24-hour of physiotherapy assistance does not reduce frequency of postoperative pulmonary complications. European Respiratory Journal. 2013; 42:P1324

- 56.

- Somerville L, Morarty J. Prioritising and managing workload demands in an acute occupational therapy service... Occupational Therapy Australia, 24th National Conference and Exhibition, 29 June - 1 July 2011. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58:49

- 57.

- Ta’eed G, Skilbeck C, Slatyer M. Service utilisation in a public post-acute rehabilitation unit following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2015; 25(6):841–863 [PubMed: 25494845]

- 58.

- Taylor L, Goodman K, Soares D, Carr H, Peixoto G, Fox P. Accuracy of assignment of orthopedic inpatients to receive weekend physical therapy services in an acute care hospital. Physiotherapy Canada. 2006; 58(3):221–232

- 59.

- Taylor NF, Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Peiris C, Sullivan N et al. A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial incorporating a health economic analysis to investigate if additional allied health services for rehabilitation reduce length of stay without compromising patient outcomes. BMC Health Services Research. 2010; 10:308 [PMC free article: PMC2998505] [PubMed: 21073703]

- 60.

- Wheat AL. Interdisciplinary team with extended therapy team working model demonstrates functional gains and short length of stay on Acute Stroke Unit. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013; 35:210

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 5Review protocol: Enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy

| Review question: Is enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy for hospital patients clinically and cost effective? | |

|---|---|

| Rationale | A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialised staff and equipment. For the hospital to function properly the individual wards must function efficiently. To enable this to happen each individual ward should be viewed as an individual unit and thus must have the relevant resources to function. Staffing is a resource of major importance and having the appropriate skill mix to function efficiently is crucial. Therapists play a crucial role in the acute management and rehabilitation of patients; therefore having adequate therapy presence should have a beneficial effect on patient outcomes. The presence of ward based AHPs was noted to be very important in influencing ward based outcomes. |

| Population |

Adults and young people (16 years and over) admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed AME. Strata:

|

| Intervention and comparators |

Presence of inpatient physiotherapists and/or occupational therapists: Intervention. 7 day services. Comparison. Less than 7 day services (standard hours defined as 9am-5pm, Monday to Friday; anything above should be considered as enhanced, studies will define). No in hospital physiotherapist and/or occupational therapist. |

| Outcomes |

Mortality (CRITICAL) Avoidable adverse events (CRITICAL) Quality of life (CRITICAL) Patient and/or carer satisfaction (CRITICAL) Length of stay (CRITICAL) Readmission up to 30 days (IMPORTANT) Discharge to normal place of residency (IMPORTANT) Time to mobilisation (IMPORTANT) Delayed transfers of care (IMPORTANT) |

| Exclusion | Exclude studies from non-OECD countries. |

| Search criteria |

The databases to be searched are: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and CINAHL. Date limits for search: 2005. Language: English only. |

| The review strategy | Systematic reviews (SR) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Analysis |

Data synthesis of RCT data. Meta-analysis where appropriate will be conducted. Studies in the following subgroup populations will be included:

|

| Key papers | None identified |

| Search terms | Assistant Practitioners (APs), who in our hospital serve the role of both OT & and physio. |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

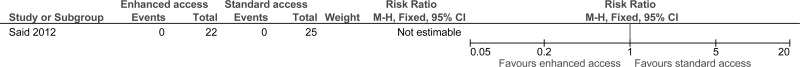

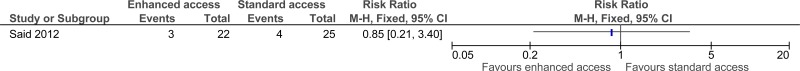

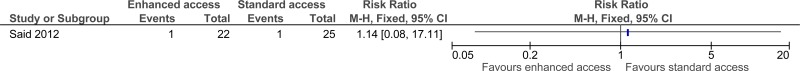

C.1. Enhanced access to therapy – Strata: the Elderly

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (333K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No relevant economic evidence was identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 6Clinical evidence profile: enhanced versus standard access to physio- and/or occupational therapy

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Weekend access | Standard access | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| STRATA: Older people | ||||||||||||

| Mortality (at discharge) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

0/22 (0%) | 0% | - | - |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (at 3 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

3/22 (13.6%) | 16% | RR 0.85 (0.21 to 3.4) | 24 fewer per 1000 (from 126 fewer to 384 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Adverse events (non-injurious fall) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

1/22 (4.5%) | 4% | RR 1.14 (0.08 to 17.11) | 6 more per 1000 (from 37 fewer to 644 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Readmission to acute hospital | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

0/22 (0%) | 0% | - | - |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | IMPORTANT |

| Quality of life (change in mobility from baseline) - Better indicated by higher values | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none | 22 | 25 | - | MD 2.4 higher (2.75 lower to 7.55 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| STRATA: Stroke | ||||||||||||

| Adverse events - Strata: Stroke | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

16/96 (16.7%) | 12.8% | RR 1.31 (0.65 to 2.61) | 40 more per 1000 (from 45 fewer to 206 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Length of rehabilitation stay (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 0 | - | - | MD 2.9 lower (17.9 lower to 12.1 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 7Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Allen 20132 | Study design and methodology paper of a RCT |

| Anon 20121 | Study protocol |

| Archer 20083 | Dissertation. Incorrect study design. Inappropriate comparison. Incorrect interventions |

| Arnold 20154 | RCT but not relevant comparison. Looking at early mobilisation of stroke patients. Not comparing access to enhanced versus standard therapy |

| Artz 20135 | Incorrect interventions. Telephone survey of current physiotherapy services offered to patients with Total hip and knee replacement in NHS hospitals in England and Wales. Incorrect study design |

| Babu 20106 | Inappropriate comparison. The study compares regular physical therapy with on-call physical therapy. |

| Baggaley 20117 | Conference abstract |

| Bernhardt 20088 | Inappropriate comparison. The study compares standard rehab with very early mobilisation (VEM) for stroke patients. VEM was defined as first mobilisation within 24 hours of stroke symptom onset. |

| Bethel 20059 | Critical appraisal of papers on the role of physiotherapists. |

| Borrows 201310 | Incorrect interventions. The study assessed the effectiveness of occupational therapy from an independent living centre compared to routine community occupational therapy service - does not look at enhanced occupational therapy compared to standard occupational therapy as stated in the protocol |

| Brandstater 201111 | Article |

| Brusco 200713 | RCT but unsure how many of the participants were orthopaedic patients. Not review population |

| Brusco 201412 | RCT but mainly orthopaedic patients. Not review population |

| Brusco 201514 | RCT but mainly orthopaedic patients. Not review population |

| Caldwell 200915 | Conference abstract |

| Campbell 200916 | Cross-sectional survey. The study describes the provision of weekend physiotherapy services in tertiary care hospitals in Canada. |

| Campbell 201017 | Cross-sectional survey via telephone interview. The aim of the study was to describe the provision of weekend physiotherapy services in a tertiary care hospital in Canada. |

| Connelly 200718 | Article |

| Connolly 201519 | incorrect comparison (SR comparing exercise programmes versus usual care without exercise) |

| Curtis 201120 | Conference abstract |

| Deane 200621 | Methodology paper on reporting of RCTs |

| Duncan 201522 | No extractable outcomes |

| English 201624 | Meta-analysis – relevant references noted |

| Gawned 201325 | Conference abstract |

| Gawned 2013A26 | Conference abstract |

| Gräsel 200527 | Wrong comparison (comparison of educational programme (that includes home treatment) versus usual care) |

| Gurr 201528 | Incorrect study design |

| Haines 201529 | A protocol for studies examining the effectiveness of current weekend allied health services and a new model for surgical/medical patients versus no weekend allied health services. |

| Hill 2010A30 | The study reports of findings from 2 focus group meetings with physiotherapists at 3 tertiary hospitals in Canada. The study aimed to describe the cardiorespiratory physiotherapy weekend service and also to compare staff burden among the clinical service areas in 1 of the hospitals that had a programme-based management structure. |

| Kalsi 201432 | Conference abstract |

| Kersten 200733 | Systematic review- relevant references noted. |

| Kolber 201334 | Inappropriate comparison. Incorrect interventions. Systematic review. Evaluates the evidence relating to the effects of frequency of physical therapy visits on acute care length of stay following knee arthroplasty. |

| Lay 201035 | Conference abstract |

| Lim 200836 | Retrospective record review. The study aimed to describe the after-hour physiotherapy services in a tertiary general hospital. |

| Maidment 201437 | No comparison. Incorrect study design. Retrospective analysis of a clinical database of patients who received either total knee or hip replacement. The study aimed to investigate a change in physiotherapy provision from a 5 to 7 days a week service. |

| Mcclellan 200638 | Qualitative study. Study evaluates the effect of an extended scope physiotherapy service on patient satisfaction. |

| Ottensmeyer 201242 | A survey about physiotherapy staffing patterns at different hospitals across Canada. No relevant comparison. |

| Paradza 201143 | Conference abstract |

| Peiris 201246 | Not review population. only orthopaedic patients |

| Peiris 2012A44 | Conference abstract |

| Peiris 201345 | mainly orthopaedic patients. Not review population |

| Reid 201047 | Conference abstract |

| Roberts 201348 | Cross-sectional survey. No comparison. The study evaluated the musculoskeletal outpatient physiotherapy service in a NHS hospital. |

| Robinson 201449 | This is a practice analysis that discusses therapy provision within the acute healthcare setting of an Emergency Assessment Unit (EAU) for medical and surgical admissions. |

| Salisbury 201051 | Incorrect interventions. Inappropriate comparison. The study compares standard physiotherapy with enhanced physiotherapy. Enhanced physiotherapy included additional interventions such as supervised passive, active and strengthening exercises, facilitation of additional transfers and mobility practice, balance exercises and advice. |

| Saxon 201452 | incorrect comparison (SR about roles of AHCP rather than extended working hours) |

| Scrivener 201553 | Systematic review. Relevant references noted. |

| Shaw 201354 | Cross-sectional survey. A national survey of physiotherapy services provided outside of business hours in Australian hospitals. |

| Silva 201355 | Conference abstract |

| Somerville 201156 | Conference abstract |

| Ta’eed 201557 | Incorrect comparison |

| Taylor 200658 | Incorrect study design. No comparison. This is a retrospective chart review of patients assigned to weekend physical therapy while staying in an inpatient orthopaedic unit. |

| Taylor 201059 | Study protocol of RCT by Pereis 2012, 2013, Brusco 2007, 2014 which has been excluded because of mainly orthopaedic patient population |

| Wheat 201360 | Conference abstract |

Appendix H. Excluded economic studies

No relevant economic evidence was identified.

- Enhanced inpatient access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy - Emergency ...Enhanced inpatient access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...