31. Enhanced in-patient access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy

31.1. Introduction

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy are an important component in the recovery from acute illness, particularly in chest disease, injurious falls, stroke and prolonged admission or with pre-existing frailty. More intense therapy would be expected to lead to shorter hospital stays and quicker recovery from immobility caused by illness. Likewise, the risk of physical deterioration from lack of access to therapies over a weekend would be expected to extend hospital stay and increase comorbidities.

Currently, 7-day services are regularly expected in specialist services such as respiratory units, and trauma units, but less so on general medical wards.

31.2. Review question: Is enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy for hospital patients clinically and cost effective?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

31.3. Clinical evidence

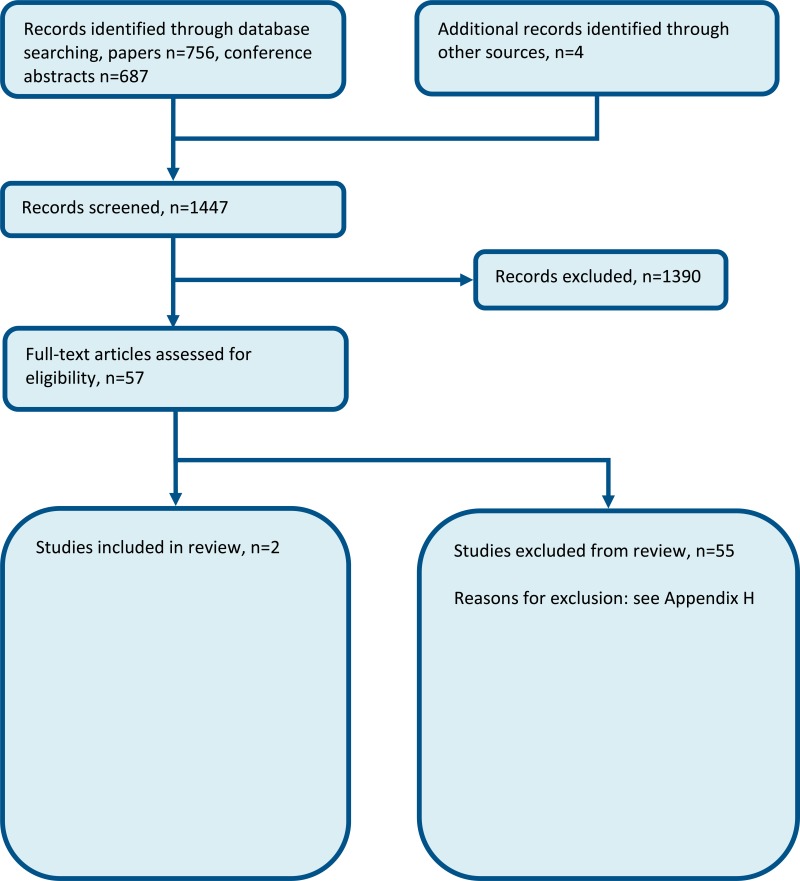

We searched for randomised controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of enhanced (7-day a week) inpatient access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy versus standard 5-day inpatient access for patients hospitalised with an acute medical emergency.

Two RCTs (3 papers) were included in the review;23,31,50 these are summarised in Table 2 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 3). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Clinical evidence profile: enhanced versus standard access to physio- and/or occupational therapy.

Narrative findings

Length of stay

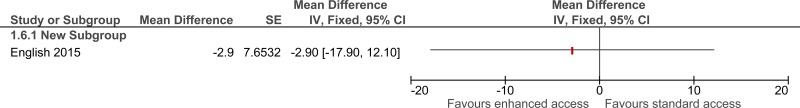

English 201523 reported a median length of stay of 45.0 days (IQR ±38.0; range 14 to 460) for the 7 day a week therapy intervention group and a median of 55.0 days (IQR ±49.0; range 14 to 240) for the usual care therapy.

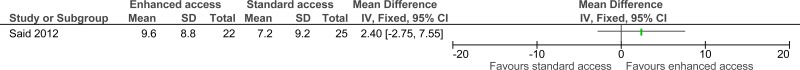

Said 201250 reported a median rehabilitation stay of 16 days (IQR 11-27.5; range 8 to 49) for the enhanced access intervention group compared to a median of 15 days (IQR 13.0-22.5; range 8 to 41) for the control group.

Quality of life

English 201523 reported the median overall score of the Australian Quality of Life scale to be 0.2 (IQR ±0.40; range −0.2 to 1.0) for the intervention group and 0.24 (IQR ±0.47; range −0.2 to 1.0) for the usual care group.

31.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

New cost-effectiveness analysis

An original cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted for this topic. This is summarised in the economic evidence profile below (Table 4) and is detailed in Chapter 41.

Table 4

Economic evidence profile: Extended access to therapy.

31.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

Older people

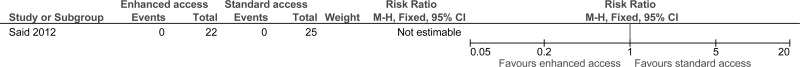

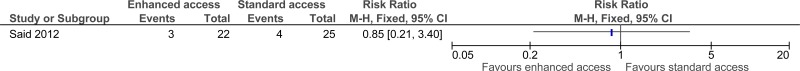

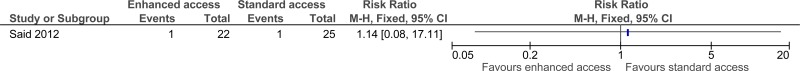

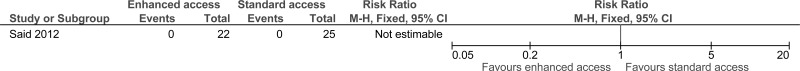

- One study comprising 47 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy for improving outcomes in secondary care in older people recovering from an AME. The evidence suggested that enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy may provide benefits in reduced mortality at 3 months (1 study, very low quality) and quality of life (1 study, moderate quality). However, there was no effect on readmission (1 study, high quality), adverse events expressed as non-injurious falls (1 study, low quality) and mortality at discharge (1 study, high quality).

Stroke

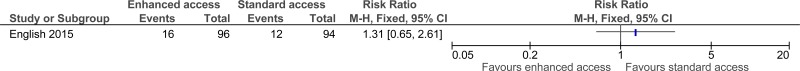

- One study comprising 283 people evaluated the role of enhanced access to physiotherapy for improving outcomes in secondary care in adults and young people who are recovering from a stroke. The evidence suggested that enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy had more adverse events - falls and other unspecified events (1 study, low quality) but did provide benefit in a reduced length of rehabilitation (1 study, high quality).

Economic

- Two original cost-utility analyses (cohort model and simulation model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people recovering from an acute medical emergency (AME) on the general medical wards was dominant, increasing QALYs and cost saving (cost difference: -£90 per patient). This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One original cost-minimisation analysis (cohort model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people presenting in the Emergency Department with a suspected AME was cost increasing (cost difference: +£0.72 per patient) . This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One original cost-utility analysis (simulation model) found that extended access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy for people recovering from an AME on the general medical wards was dominated by standard access. This analysis was assessed as directly applicable with potentially serious limitations.

31.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

References

- 1.

- A trial to evaluate an extended rehabilitation service for stroke patients. Health Technology Assessment, 2012. Available from: http://www

.nets.nihr .ac.uk/__data/assets /pdf_file/0007/81664/PRO-10-37-01.pdf - 2.

- Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Walker TA, Bartle J, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ et al. Group physical therapy for veterans with knee osteoarthritis: study design and methodology. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013; 34(2):296–304 [PMC free article: PMC8443150] [PubMed: 23279750]

- 3.

- Archer KR. Determinants of referral to physical therapy: influence of patient work status and surgeon efficacy beliefs Johns Hopkins University; 2008.

- 4.

- Arnold SM, Dinkins M, Mooney LH, Freeman WD, Rawal B, Heckman MG et al. Very early mobilization in stroke patients treated with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015; 24(6):1168–1173 [PubMed: 25869770]

- 5.

- Artz N, Dixon S, Wylde V, Beswick A, Blom A, Gooberman-Hill R. Physiotherapy provision following discharge after total hip and total knee replacement: a survey of current practice at high-volume NHS hospitals in England and Wales. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013; 11(1):31–38 [PubMed: 22778023]

- 6.

- Babu AS, Noone MS, Haneef M, Samuel P. The effects of ‘on-call/out of hours’ physical therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010; 24(9):802–809 [PubMed: 20543018]

- 7.

- Baggaley K, Benn S, Eastwood M, Robinson K, Shaw K, Wirtz A et al. Opening Pandora’s box: describing the scope of occupational therapy practice in a community health service in Victoria... Occupational Therapy Australia, 24th National Conference and Exhibition, 29 June - 1 July 2011. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58:28

- 8.

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. a journal of cerebral circulation 2008; 39(2):390–396 [PubMed: 18174489]

- 9.

- Bethel J. The role of the physiotherapist practitioner in emergency departments: a critical appraisal. Emergency Nurse. 2005; 13(2):26–31 [PubMed: 15912710]

- 10.

- Borrows A, Holland R. Independent living centre occupational therapy (OT) versus routine community OT. International Journal of Therapy & Rehabilitation. 2013; 20(4):187–194

- 11.

- Brandstater ME. Physical medicine and rehabilitation and acute inpatient rehabilitation. PM and R. 2011; 3(12):1079–1082 [PubMed: 22192318]

- 12.

- Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Taylor NF. Are weekend inpatient rehabilitation services value for money? An economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial with a 30 day follow up. BMC Medicine. 2014; 12(2):89 [PMC free article: PMC4053313] [PubMed: 24885811]

- 13.

- Brusco NK, Shields N, Taylor NF, Paratz J. A Saturday physiotherapy service may decrease length of stay in patients undergoing rehabilitation in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2007; 53(2):75–81 [PubMed: 17535142]

- 14.

- Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Taylor NF. Is cost effectiveness sustained after weekend inpatient rehabilitation? 12 month follow up from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2015; 15:165 [PMC free article: PMC4438580] [PubMed: 25927870]

- 15.

- Caldwell KE, Hughes L, Sturt R. Audit to establish the impact of staffing levels on the quality and intensity of physiotherapy treatment of stroke patients against Royal College of Physicians (RCP) guidelines. International Journal of Stroke. 2009; 4:28

- 16.

- Campbell L, Bunston R, Colangelo S, Kim D, Nargi J, Brooks D et al. The provision of weekend physical therapy services in university-affiliated hospitals with an intensive care unit in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2009; 61:54

- 17.

- Campbell L, Bunston R, Colangelo S, Kim D, Nargi J, Hill K et al. The provision of weekend physiotherapy services in tertiary-care hospitals in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010; 62(4):347–354 [PMC free article: PMC2958077] [PubMed: 21886374]

- 18.

- Connelly RS, Thomas PW. Solving the riddle of inpatient rehabilitation coverage. Healthcare Financial Management. 2007; 61(3):98–104 [PubMed: 19097629]

- 19.

- Connolly B, Salisbury L, O’Neill B, Geneen L, Douiri A, Grocott Michael PW et al. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; Issue 6:CD008632. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008632.pub2 [PMC free article: PMC6517154] [PubMed: 26098746] [CrossRef]

- 20.

- Curtis A, Ainsworth H, Anderson J, Osman L. Functional outcome measures on discharge from intensive care: an evaluation of an extended seven day working pilot. Intensive Care Medicine. 2011; 37:S271

- 21.

- Deane KHO. Randomised controlled trials: part 2, reporting. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006; 69(6):248–254

- 22.

- Duncan C, Hudson M, Heck C. The impact of increased weekend physiotherapy service provision in critical care: a mixed methods study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2015; 31(8):547–555 [PubMed: 26467461]

- 23.

- English C, Bernhardt J, Crotty M, Esterman A, Segal L, Hillier S. Circuit class therapy or seven-day week therapy for increasing rehabilitation intensity of therapy after stroke (CIRCIT): a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2015; 10(4):594–602 [PubMed: 25790018]

- 24.

- English C, Shields N, Brusco NK, Taylor NF, Watts JJ, Peiris C et al. Additional weekend therapy may reduce length of rehabilitation stay after stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2016; 62(3):124–129 [PubMed: 27320831]

- 25.

- Gawned S, Lindfield H, Cooke EV. A ‘7 day service’ for therapies: providing an expanded weekend stroke service. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013; 35:771

- 26.

- Gawned SL, Lindfield HE, Eddison J, Cooke EV. Seven day stroke therapy services - developing a weekend service on the hyperacute stroke unit. International Journal of Stroke. 2013; 8:63

- 27.

- Gräsel E, Biehler J, Schmidt R, Schupp W. Intensification of the transition between inpatient neurological rehabilitation and home care of stroke patients. Controlled clinical trial with follow-up assessment six months after discharge. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005; 19(7):725–736 [PubMed: 16250191]

- 28.

- Gurr B, Dendle J. Assessment of stroke survivors on an inpatient rehabilitation unit. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing.: MA Healthcare Limited. 2015; 11(4):179–184

- 29.

- Haines TP, O’Brien L, Mitchell D, Bowles K-A, Haas R, Markham D et al. Study protocol for two randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness and safety of current weekend allied health services and a new stakeholder-driven model for acute medical/surgical patients versus no weekend allied health services. Trials. 2015; 16(1):133 [PMC free article: PMC4403707] [PubMed: 25873250]

- 30.

- Hill K, Brooks D. A description of weekend physiotherapy services in three tertiary hospitals in the greater Toronto area. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010; 62(2):155–162 [PMC free article: PMC2871025] [PubMed: 21359048]

- 31.

- Hillier S, English C, Crotty M, Segal L, Bernhardt J, Esterman A. Circuit class or seven-day therapy for increasing intensity of rehabilitation after stroke: protocol of the CIRCIT trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2011; 6(6):560–565 [PubMed: 22111802]

- 32.

- Kalsi S, Allum L, Thomas A, Patel M, McDonald H. An audit and observation of current practice: the impact of physiotherapy seven-day working in intensive care. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2014; 15:(Suppl 1):S43–S44

- 33.

- Kersten P, McPherson K, Lattimer V, George S, Breton A, Ellis B. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice - who is doing what and why? Physiotherapy. 2007; 93(4):235–242

- 34.

- Kolber MJ, Hanney WJ, Lamb BM, Trukman B. Does physical therapy visit frequency influence acute care length of stay following knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2013; 29(1):25–29

- 35.

- Lay J, O’Shea H, Loughborough B, Potter J, Guyler PC, O’Brien A. 7 Day-a-week rehabilitation in a united kingdom district general hospital stroke unit reduces patient length of stay and improves patient satisfaction with the stroke service. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010; 29:337

- 36.

- Lim ECW, Liu J, Yeung MTL, Wong WP. After-hour physiotherapy services in a tertiary general hospital. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2008; 24(6):423–429 [PubMed: 19117233]

- 37.

- Maidment ZL, Hordacre BG, Barr CJ. Effect of weekend physiotherapy provision on physiotherapy and hospital length of stay after total knee and total hip replacement. Australian Health Review. 2014; 38(3):265–270 [PubMed: 24804607]

- 38.

- McClellan CM, Greenwood R, Benger JR. Effect of an extended scope physiotherapy service on patient satisfaction and the outcome of soft tissue injuries in an adult emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006; 23(5):384–387 [PMC free article: PMC2564090] [PubMed: 16627842]

- 39.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Venous thromoembolism: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) inpatients admitted to hospital. NICE clinical guideline 92. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. Available from: http://www

.nice.org.uk/CG92 - 40.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. The management of hip fracture in adults. NICE clinical guideline 124. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2011. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG124 - 41.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). NICE clinical guideline 68. London. Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG68 [PubMed: 21698846] - 42.

- Ottensmeyer CA, Chattha S, Jayawardena S, McBoyle K, Wrong C, Ellerton C et al. Weekend physiotherapy practice in community hospitals in Canada. Physiotherapy Canada. 2012; 64(2):178–187 [PMC free article: PMC3321989] [PubMed: 23449882]

- 43.

- Paradza B. 7-Day physiotherapy pathway reduces hospitalisation following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) when compared to 5-day pathway-a service evaluation study. Physiotherapy. 2011; 97:eS963

- 44.

- Peiris C, Shields N, Taylor NF. Extra physical therapy and occupational therapy increased physical activity levels in orthopedic rehabilitation: randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93(10):E14 [PubMed: 22446517]

- 45.

- Peiris CL, Shields N, Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Taylor NF. Additional Saturday rehabilitation improves functional independence and quality of life and reduces length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Medicine. 2013; 11:198 [PMC free article: PMC3844491] [PubMed: 24228854]

- 46.

- Peiris CL, Taylor NF, Shields N. Additional Saturday allied health services increase habitual physical activity among patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for lower limb orthopedic conditions: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93(8):1365–1370 [PubMed: 22446517]

- 47.

- Reid A, Hills L. A pilot study to assess the impact of a seven-day therapy service on a stroke unit. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010; 29:151–152

- 48.

- Roberts L. Improving quality, service delivery and patient experience in a musculoskeletal service. Manual Therapy. 2013; 18(1):77–82 [PubMed: 22609270]

- 49.

- Robinson A, Lord-Vince H, Williams R. The need for a 7-day therapy service on an emergency assessment unit. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 77(1):19–23

- 50.

- Said CM, Morris ME, Woodward M, Churilov L, Bernhardt J. Enhancing physical activity in older adults receiving hospital based rehabilitation: a phase II feasibility study. BMC Geriatrics. 2012; 12:26 [PMC free article: PMC3502428] [PubMed: 22676723]

- 51.

- Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL, Walsh TS. The development and feasibility of a ward-based physiotherapy and nutritional rehabilitation package for people experiencing critical illness. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010; 24(6):489–500 [PubMed: 20410151]

- 52.

- Saxon RL, Gray MA, Ioprescu F. Extended roles for allied health professionals: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2014; 7:479–488 [PMC free article: PMC4206389] [PubMed: 25342909]

- 53.

- Scrivener K, Jones T, Schurr K, Graham PL, Dean CM. After-hours or weekend rehabilitation improves outcomes and increases physical activity but does not affect length of stay: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2015; 61(2):61–67 [PubMed: 25801362]

- 54.

- Shaw KD, Taylor NF, Brusco NK. Physiotherapy services provided outside of business hours in Australian hospitals: a national survey. Physiotherapy Research International. 2013; 18(2):115–123 [PubMed: 23038214]

- 55.

- Silva JM, Rotta BP, Padovani C, Ramos M, Fu C, Tanaka C. 24-hour of physiotherapy assistance does not reduce frequency of postoperative pulmonary complications. European Respiratory Journal. 2013; 42:P1324

- 56.

- Somerville L, Morarty J. Prioritising and managing workload demands in an acute occupational therapy service... Occupational Therapy Australia, 24th National Conference and Exhibition, 29 June - 1 July 2011. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58:49

- 57.

- Ta’eed G, Skilbeck C, Slatyer M. Service utilisation in a public post-acute rehabilitation unit following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2015; 25(6):841–863 [PubMed: 25494845]

- 58.

- Taylor L, Goodman K, Soares D, Carr H, Peixoto G, Fox P. Accuracy of assignment of orthopedic inpatients to receive weekend physical therapy services in an acute care hospital. Physiotherapy Canada. 2006; 58(3):221–232

- 59.

- Taylor NF, Brusco NK, Watts JJ, Shields N, Peiris C, Sullivan N et al. A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial incorporating a health economic analysis to investigate if additional allied health services for rehabilitation reduce length of stay without compromising patient outcomes. BMC Health Services Research. 2010; 10:308 [PMC free article: PMC2998505] [PubMed: 21073703]

- 60.

- Wheat AL. Interdisciplinary team with extended therapy team working model demonstrates functional gains and short length of stay on Acute Stroke Unit. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013; 35:210

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 5

Review protocol: Enhanced access to physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy.

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

C.1. Enhanced access to therapy – Strata: the Elderly

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (333K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No relevant economic evidence was identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 6

Clinical evidence profile: enhanced versus standard access to physio- and/or occupational therapy.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 7

Studies excluded from the clinical review.

Appendix H. Excluded economic studies

No relevant economic evidence was identified.

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), London

NLM Citation

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.) Chapter 31, Enhanced inpatient access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy.