Abbreviations

- PWUD

People Who Use Drugs

- EMS

Emergency Medical Services

Context and Policy Issues

Canada is in the midst of an opioid crisis. The number of deaths due to opioids has increased from 3,023 in 2016 to 4,588 in 2018.1 In 2018, this equated to the life of one Canadian being lost every 2 hours as a result of opioid use. The increase in opioid-related deaths has been attributed to a number of different causes. The increased contamination of street drugs due to fentanyl is one reason, with estimates of the percent of opioid deaths due to fentanyl or fentanyl analogues having increased from 50% in 2016 to 79% in 2019.1 Prescription opioids have also contributed to the crisis. The volume of opioids sold to Canadian hospitals and pharmacies has increased by more than 3000% since the early 1980’s, with over 20 million prescriptions dispensed for opioids in 2016 alone.2 Addressing the opioid crisis has been complicated by the fact that the use of opioids is illegal in Canada, unless prescribed by a physician. Therefore, many opioid users buy opiates illegally on the street, and these opiates have unknown strength and may be contaminated with other drugs such as fentanyl. In addition, those who face addictions are frequently greeted with stigma, rather than an understanding of their addiction and mental health problems. To help address these issues, a Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act was enacted so that those who call for help when an overdose occurs are protected from drug possession charges.

The distribution of naloxone kits in the community is one strategy being implemented internationally to reduce the number of opioid-related deaths. Naloxone is a powerful anti-opioid drug, which temporarily blocks the effect of the opioid on the body.2 Furthermore, it is not harmful for those who have not been exposed to opioids. In Canada, take-home naloxone kits are available at most pharmacies without a prescription and are free in some provinces.3,4 The naloxone kits include naloxone nasal spray or naloxone intramuscular injection.5 Both take less than five minutes to take effect.5 For these reasons, the distribution of naloxone kits in the community has been a powerful tool to save the lives of those who have experienced an overdose due to opioid use, and there has been increased efforts to expand the availability of naloxone in the community setting.

This purpose of this report was to explore the experience of administering naloxone in the home and community setting and to explore whether this experience differs between those who may typically administer naloxone, including paramedics and peers or people who use drugs (PWUD). Understanding the administration of naloxone from the perspective of the person administering it is useful for a number of different reasons. It can highlight the challenges and advantages of using naloxone from the perspective of the user, and can shed light on the emotional consequences of dealing with the opioid crisis.

Research Questions

How is accessing and administering naloxone in a home or community setting experienced by community and lay users, community service staff, police and other non-healthcare professionals?

How is administering naloxone in a community setting experienced by paramedics?

Key Findings

This review presents a thematic analysis of the results of 11 included studies and reveals both the promise and the challenges of administering naloxone in the home and community setting. Experiences emerged as different across groups who typically administer naloxone, including Emergency Medical Service (EMS) workers, police, and peer responders.

Naloxone can save lives, and was therefore viewed as consistently rewarding for responders. An overdose event can be a pivotal moment in the lives of both opioid victims and peer responders. Some explained that they initiated harm reduction activities subsequent to the overdose event, suggesting an impact on people’s lives beyond the act of administering naloxone. Uniquely, police officers felt they were well positioned to administer naloxone because they were often the first to arrive at the scene of an overdose. Furthermore, they thought it could contribute to improved relationships within the community.

EMS workers at times described frustration and burnout when they were called upon to revive the same patient on more than one occasion. The view that opioid users were less deserving than some other emergency victims was expressed by some. The use of opioids was viewed as a ‘choice’ in these cases and therefore the emergency was viewed as self-inflicted. These results suggest that EMS workers may benefit from an increased understanding of mental health and addictions, which may help reduce stigmatizing attitudes towards opioid users and overdose victims.

The experience of administering naloxone can be challenging because it can throw the overdose victim into withdrawal, which can lead to angry, violent confrontations with those around them. EMS workers and peer responders who were experienced with naloxone administration described that they were able to titrate doses so that the survivor was revived but not sufficiently awake to be angry or violent. This was a particularly important strategy when transportation times to the hospital were long, for example in rural settings. This was a strategy that was also viewed as favourable for the victim, as a sudden withdrawal can lead to extreme urges to return to using opioids immediately.

Peer responders have the advantage of often being present when an overdose occurs; however, they noted that recognizing an overdose event is not always straightforward, and often occurs in a context of anxiety and panic. Some described a hesitancy to call 911 as this may jeopardize their housing status, and introduce fear of prosecution. Peer responders described emotional exhaustion when they were called on to intervene frequently and when they had a close relationship with an opioid victim. They explained that sometimes their intervention led to altered interpersonal relationships with the victim, which could be negative or positive.

The results reveal that peer responders’ sense of competency appears to be strengthened when they are praised by paramedics, suggesting that paramedics can play an important role in terms of their social interaction with others, and not just in terms of their technical competencies.

Several participants across the included studies expressed frustration that administering naloxone does not address the root cause of the opioid crisis in their communities.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Scopus. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concepts were naloxone and community, home, or paramedic administration. Search filters were applied to limit retrieval to qualitative studies. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents. The search was run on November 1, 2019 and was not limited by publication date.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed. Subsequently, the full-text of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they were not published in English or did not meet the inclusion criteria outlined in .

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included studies were critically appraised by one reviewer using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist,6 as a guide. Summary scores were not calculated to describe the quality of included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively. Results of the critical appraisal were not used to exclude studies from this review.

Data Analysis

One reviewer conducted the analysis, using Nivo9 from QSR international7 to manage the data. Coding was done iteratively. Initial codes were based on the themes and concepts derived by the authors of the included studies; however, codes and themes were changed, revised and reconceptualized throughout the coding and writing process to meet the objectives of this review.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

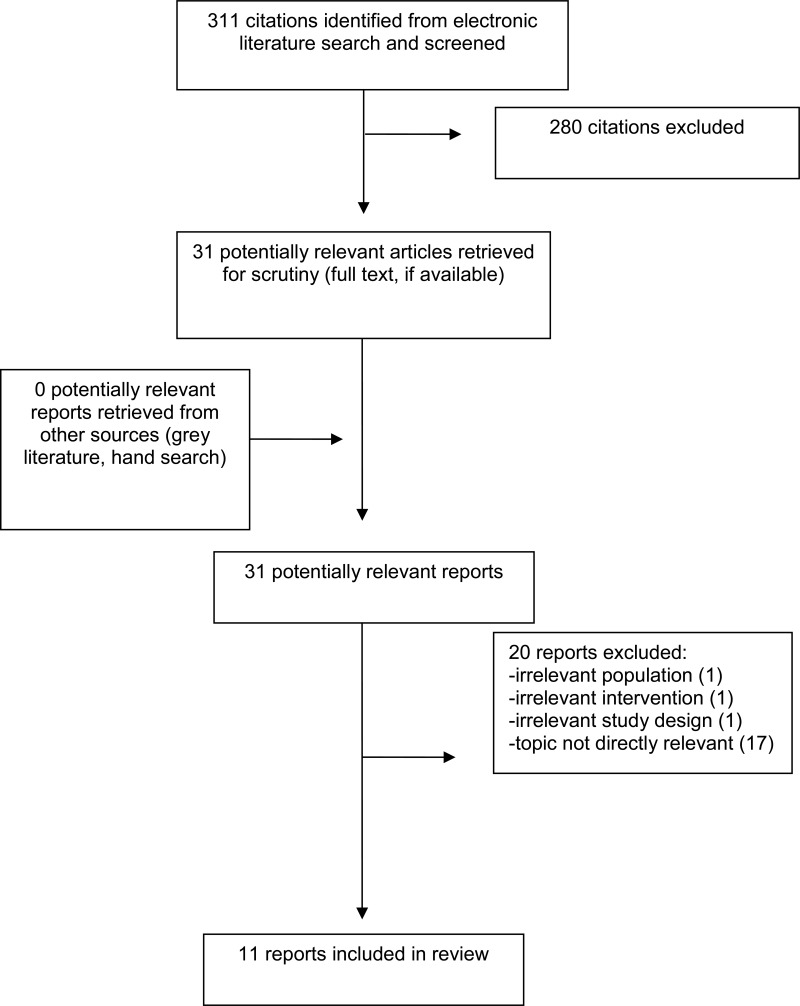

A total of 311 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 280 citations were excluded and 31 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 20 were excluded for various reasons, and 11 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA8 flowchart of the study selection process.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study Design

Eleven qualitative studies are included in this review. Of these, one study used an Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis approach9 and another used a community-based research approach.10 The other nine studies did not provide any detail about their orientation beyond reporting a generic “qualitative” approach.

Country of Origin

One study was conducted in Canada.10 Three studies were conducted in the UK.11–13 Six studies were conducted in the USA,14–19 and one study was conducted in China.20

Participant Populations

Seven studies explored the experience of administering naloxone from the perspective of peer responders. These are drug users who had access to naloxone and received some training with regards to overdose response and naloxone administration.9–11,13,17,19,20

Four studies explored the experiences of administering naloxone from the perspective of emergency responders.14–16,18 One study reported on the experience of emergency responders, including police officers, emergency department workers and opioid survivors.14 Another reported on the experience EMS workers, emergency department medical staff and opioid survivors.15 Another reported on the experience of using naloxone among EMS workers,16 and another the experiences of law enforcement officers.18

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications and their participants are provided in Appendix 2 and 3.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

All studies identified for this review used qualitative methods appropriately. The questions asked and the data collection methods used to answer these questions were also appropriate.

Many of the articles were under-theorized. Events and perspectives were typically described but not lumped into conceptual categories. Two articles were an exception to this tendency.9,10 The paper by McAuley used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and usefully distinguished between the psychological impacts of naloxone administration, behavior change and peer responses. Furthermore, the paper related the results to role theory.9 The paper by Kolla related individual experience and behavior to broader social and political factors, such as the illicit nature of opioid drugs.10

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 4.

Summary of Findings

Our search revealed that qualitative research had been conducted with three groups of people who administer naloxone in the home or community setting. These groups are: EMS workers, police officers, and peers (other people who use drugs). The experience of administering naloxone emerged as different for each group, and therefore, the analysis is presented differently for each.

The experience of administering naloxone also appeared to be influenced by other factors such as whether an experience was the first time administering naloxone or the person was highly experienced, the relationship of the overdose victim to the person administering naloxone, and the political context, such as the laws regarding opioid use. These other factors are described in the analysis where appropriate to demonstrate their influence on the experience of administering naloxone.

For each group, the findings are summarized into the following categories where the data allowed: the tasks performed - the response to the overdose and why decisions were made; the perspectives – the perspective of the responder regarding their role; the emotional state of the responder and how administration of naloxone may lead to altered interpersonal relationships.

For some groups there was less research than for others. Therefore, not all categories are described for each group. For instance, two articles discussed the experience of police officers administering naloxone and these articles did not provide details of the tasks that the police officers performed nor of their emotional states when administering naloxone. Peer responders was the only group that had research to support how the administration of naloxone could lead to altered interpersonal relationships.

EMS workers

Research on the experience of administrating naloxone by EMS workers provides details about the challenges of their role. EMS workers described the challenge of sending an opioid overdose victim into immediate withdrawal and how they took steps to minimize this. They spoke about their interactions with the patient, and some noted that their excitement about saving lives at times gave way to feelings of burnout.

The Tasks: titrating naloxone for opioid users “to make it safer for everyone”

All three studies that explored the experiences of administering naloxone from the perspective of emergency responders reported that some EMS workers who administered naloxone had learned how to titrate doses when reviving opioid addicted drug users (while performing ventilation)14 so that the person recovered breathing but avoided being sent into immediate withdrawal.14–16 As one participant put it: “’we just give them enough to get the effect, to get them breathing on their own” (p3).16 This strategy and learning how to titrate doses was also described as: “I think we have become a lot more nuanced in how we use Narcan, so we’ve learned to tailor it to, really, just their respiratory drive as opposed to having them wide awake, sitting upright, staring at you in withdrawal” (p142).14

Titration was seen to be desirable for both the patient and the EMS worker. For the EMS worker, it avoids interaction with an angry potentially violent patient, for example: “If we give them too much of this, we will send them into withdrawals. They’ll throw up, they’ll seize, they’ll fight. They are really mad at you for taking away their high…It becomes a patient rodeo- they come out mad” (p3).16 For the patient, titration can minimize the very difficult and painful symptoms of withdrawal. This is important because some users have noted that naloxone administration and severe withdrawal symptoms can lead to an urgent desire to use again to eliminate the withdrawal symptoms. In this situation, the overdose victim can mistakenly believe that they are no longer high, and further opioid use could lead to subsequent death.14

EMS responders working in remote or rural areas expressed the view that titration was important because the transportation times to hospitals were long, and access to law enforcement in cases of a combative patient was limited.16 One EMS worker stated that “longer transport times mean that we often titrate and give lower doses to make the patient less combative, making the situation safer for everyone” (p3).16

In addition, EMS workers expressed a concern that administration of naloxone by intravenous needle introduced an additional safety hazard for workers in the ambulance:

When you gave an IV, if you administered it too fast, people would wake up instantly. They would be incredibly violent and angry, so now you have an angry combative patient and a contaminated sharp needle in the back of a very small ambulance, and that posed a huge risk for us. (p147)14

By contrast to these accounts of overdose by people who use drugs (PWUD), for accidental overdoses by pediatric or elderly patients who may use opioids as a medical treatment for pain, for example, EMS “participants reported that the drug could be safely administered depending on patient size and mobility and that titration was less necessary” (p3).16

The tasks: interactions with the overdose patient

In one study, some of the EMS responders reported that they preferred avoiding what they perceived as unnecessary conversations with opioid overdose survivors.15 However, all respondents spoke about having engaged in these at some point, and discussing the overdose event with the survivor. In some accounts, EMS workers took on the role of educators explaining how drug misuse could destroy vital organs and lead to death. As one EMS worker noted: “I don’t have a standard line, but you do want to talk to them about [their OD] really” (p1381).15

This study did not discuss the impact of these interactions on the survivor, or the perspective of survivors of participating in these types of educational conversations with EMS workers. However, this study did show that, among survivors, most described undertaking harm-minimizing changes (e.g. attempts to cease heroin use, ceasing mixing heroin with other drugs, not taking drugs alone, initiating methadone-assisted treatment) subsequent to an overdose reversal. This suggests that an overdose event and subsequent revival through naloxone administration can be a crucial turning point for some opioid users.15

Perspectives on their Role and their Emotional State

Two studies reported how administering naloxone can be rewarding to EMS workers because it enabled them to save lives.14,15 However, the research also revealed that these positive feelings can give way to negative ones, particularly when they are called on to rescue the same person again, for example: “You know at the beginning it was exciting. I saved their lives. Now…there are frequent flyers and we see them over and over again and it comes to a realization. We’re like ‘Okay we saved you this time. For what? For you to do it again?’” (p1382).15

A study of EMS workers in New York city suggested that treating drug overdoses can exert a heavy emotional toll on EMS workers.15 Many participants expressed feelings of frustration, fatigue, or burnout. Their accounts suggest that in particular they experience frustration in situations in which they saved a life but then, they are called on to rescue the same person again. For some workers their feelings of emotional exhaustion appear to stem from their view that the patient who overdosed does not appear to want help or is less deserving because the opioid drug was self-inflicted. For some EMS workers they view opioid use as a poor choice, rather than as a result of a mental health disorder and addiction.

You might have a day where you get two or three [ODs] from a bad batch going around. It’s just like we see the same people, the same type of person…It kind of weighs on you because you feel like they don’t want help. It’s totally different from someone who gets in a car accident on their way to school or work…really trying to live their life. (p1381)15

Furthermore, some EMS workers also noted that the administration of naloxone does not address the root cause of the opioid epidemic in their community: “Are we reacting or dealing with the root causes [of the increased naloxone use]?” (p3).16 or “It’s kind of a crutch; it’s kind of a band-aid. It’s not a long-term solution to a chronic problem the community is facing” (p147).14

These accounts suggest that EMS workers can, at time, perceive their role in somewhat futile terms. They save a life, yet the “save” is temporary, as they may see the user again in the same overdose state, or they save a life for someone whom they perceive may not want to be saved. These situations appear to contribute to a sense of emotional exhaustion and burnout, and at times resentment towards the opioid overdose victims.

Police Officers

Two studies reported on the use of naloxone by police officers. These studies did not provide details about how police officers performed their tasks or their emotional responses; however, they did provide insights into how they perceived their role. These accounts suggest that police officers can have the view that administering naloxone is a useful component to their role, as they often arrive first at the scene of an overdose and this lifesaving act can be good for community relationships.

Perspectives on their role: useful, good for community relationships

Police offices expressed many views that were similar to other EMS responders. They noted that naloxone was a powerful tool to save lives14,18 and that the intranasal administration of naloxone was perceived as relatively simple.18 These positive perceptions of naloxone were tempered by views that even though a life may be saved, the opioid victim is often angry that their high is ruined14 and may overdose again.18

Some perspectives were unique to police officers, as they contrasted the task of administering naloxone to that of their regular duties. Some described that it may be useful for police officers to have a naloxone kit because they often arrive at an overdose scene before paramedics: “I think it should be rolled out to all cops because like I said, we get there first 90 percent of the time and we might as well spray something up someone’s nose and save their life” (p26).18 Officers further explained that compared to their usual tasks, administering naloxone could be more rewarding and lead to improved community relationships. As one deputy remarked, it can be rewarding to save a life and to know the outcome of the event:

In a lot of cases where we’re first at a scene and are providing first aid we never find out what happens to the person after EMS or FD [fire department] cart them away … Did they die or survive? Did I save that guy’s life or not? Whereas with naloxone you get to see the result immediately, and you know what happened to that person. (p26)18

It also appears that officers were aware that administering naloxone could have a favourable impact on relationships within the community. At times, they described receiving explicit thanks from bystanders for their role in saving a life via naloxone. One deputy suggested that this role might have an impact by increasing the likelihood that bystanders call 911 in the event of a future overdose: “All those people [on a landing overlooking the scene] saw us use naloxone on someone rather than just arrest people or wait for paramedics” (p26).18

Peer Responders

The third group of participants that is described in the research literature is the administration of naloxone by peers, or PWUDs.

For peer responders, administering naloxone is described as only one part of the process of responding to an overdose event. There is first the challenge of identifying if an overdose has actually occurred, then there are first aid responses, the decision of whether or not to call 911, and finally the administration of naloxone. Each step within this sequence of events has impact on the emotional state of the peer responder and possibly on interpersonal relations with the opioid victim.

The Tasks: Responding to an overdose event

Identifying an overdose event

Two studies of peer responders, most of whom had received some training in naloxone administration,11,13 indicated that identifying an overdose event could often be challenging. Sometimes, the identification of an overdose victim was straightforward as they see someone staggering, falling over or lying on the ground, or they hear a bystander call for help.13 However, at other times, victims chose to inject in private where witnesses were not present. Peers explained that users may go off to use on their own because they don’t want to share their opioids with other users, or they are injecting into the groin.11 Participants explained that sometimes the victim was only discovered by luck or by chance, and sometimes that was too late.11 Sometimes, the witnesses were intoxicated themselves and that delayed the recognition of an overdose event.11,19 In addition, peer responders noted that it could be difficult to tell if the victim was overdosing or just heavily intoxicated,11,13 particularly since some opiate users attempt to achieve a state of intoxication resembling deep sleep or coma.11 Additionally, some witnesses were reluctant to ruin someone’s else’s high, for example: “A lot of the time people seem to think you’re going over but you’re not, you’re just grouching out. You get pretty pissed off when someone tries to bring you back round again” (p59).11

However, other peers described checking up on fellow users. One participant for example described how he would routinely shake fellow users even if it meant ruining their high: “So now I don’t care if I’m spoiling somebody’s buzz to be honest. I’d rather know – you’re in my company – so I’d rather know you’re all right…Just by me shaking them would have brought them round. So what if I’m spoiling your buzz – tough” (p59).11

First responses, folk remedies, first aid

After peers had determined that an overdose had occurred, many reported trying to stimulate the victim in some way, either by using the first aid they had been taught in naloxone training sessions,13 or using various folk remedies such as pouring cold water, walking the person around, shouting their name, or slapping them.11,17 Other measures included mobilizing support from others13 and moving the victim into a recovery position.11,13 Peers reported using some of the methods instead of, or before, calling an ambulance, or while waiting for an ambulance to arrive.11

Calling 911

Calling emergency services is a key message delivered to those who are trained in the use of naloxone. The included studies, however, indicate that peers sometimes debated whether or not to call 911, as a 911 call can draw police to the scene as well as paramedics. Peers reported fearing prosecution,13 in particular for those with previous or ongoing criminal justice involvement17 such as outstanding warrants for arrest.11 There was also the fear of prosecution for being in possession of illegal substances,11,19 and for administering illegal substances, such as opioids to the overdose victim.11,17

In addition, there was the fear that a 911 call could have negative consequences for the victim or the peer responder in terms of their housing.10,11,17,20 Some jurisdictions, such as Canada, have instituted Good Samaritan legislation that protects individuals from prosecution against simple drug possession at the scene of an overdose;10 however, this legislation does not address the fact that individuals can be evicted for using illicit drugs in their homes.10 Those who lived in subsidized or social housing spoke of incidents in which eviction proceedings were initiated against other tenants following calls to 911 due to overdose.10 “It [Good Samaritan Act] doesn’t address the housing issue. It addresses the police issue, but it doesn’t address if you’re in a building that doesn’t want any type of drugs” (p132).10

Those who did call 911, despite these risks, consistently expressed sentiments such as “’somebody’s life is on the line” or “I had to do what I had to do” (p5).17,19 Sometimes, peers explained that they found it easy to call 911 when the overdose occurred in a public location and they could leave the scene if necessary.11,17

Administering Naloxone

Studies with peer responders indicate that sometimes the administration of naloxone was delayed because the responder’s kit was not with them. Users might store their kit at their home, shelter room, or car, or with a family member or at a friend’s house.11,13 In some cases, the 5 or 10 minute delay caused by the need to retrieve a kit could lead to fatal consequences:11 “It took me about five, ten minutes then, to ride home on my bike, get the naloxone, come back and administer it. And it was too late, I think; he was already dead by then” (p60).11

In the included studies, generally peer responders felt capable of administering naloxone;17 however, sometimes they reported being nervous or uncertain11,13 and sometimes expressed the desire for follow up training. In the one study that raised the desire for further training, peers were using intramuscular naloxone.11

Another reason for hesitancy in using naloxone is its potential to throw the victim into post-resuscitation distress.11,13 Because of this, peers in one study emphasized that they would not give naloxone unless it was essential, and the victim was “unresponsive, not breathing, blue or likely to die” (p713).13 However, others rationalized that they administered naloxone regardless, as they had learned in training that it could do no harm.13

A few studies noted that there was some uncertainty in terms of how much naloxone to use,21 and how much time to wait before administering a second dose.13 Sometimes users reported administering a second dose immediately, even though they had been told to wait, because the victim had not regained consciousness13 indicating that the effect of naloxone took longer to work than they anticipated. Two studies also reported that users administered a second or third dose even though the victim had already regained consciousness9,13: For example, “[s]he was breathing but it was very, very labored so that’s why I administered the second dose. Because she didn’t come out of it with the first one” (p714).13

Similar to EMS workers, one study reported that participants who had more experience in administering naloxone likewise calibrated how much naloxone was used to avoid initiating withdrawal symptoms within the victim.17

Perspectives on their Role and their Emotional State

An emotional roller coaster

Observing an overdose evokes a strong emotional reaction in peers.9,10,19 The emotional journey begins at the onset of the recognition of a peer’s overdose and continues right through and after the peer has been sent to hospital.

Many respondents reported a sense of panic and anxiety about witnessing an overdose. Peer responders at times reported feeling uncertain about whether they had done things correctly or in the right order. Others stated that they had felt anxious but had still remembered what they had been taught in the training session.13 There is both the concern that they knew how to respond appropriately, and the concern about the perilous state of the victim.9,19 “Every time I’ve been in a situation where someone ODs. It’s a panic, and…I’ve always kept my cool, but everybody else around and yellin’ and screamin’…and losin’ their head….they’re scared for this person’s life” (p4).19

Pride and Relief

One study described how feelings of alarm and anxiety gave way to a sense of pride and relief when they saw the naloxone working effectively, saving a life, and allowed them to reflect on their own role as a “lifesaver”9: “…as soon as he started to come around and that and I thought…I was quite relieved, quite proud to… I’ve never felt like that before as I say, as I say that was my first, my first mate I’ve ever saved” (p49).9

A number of peer responders described how empowering this experience was for them. McAuley theorized that the identity of a lifesaver was derived due to the praise that they received from peers and more specifically from professionals.9 In one reported example, the ambulance attendants praised one peer’s competency in terms of being capable to intervene in future overdose events: “When they came they were like, ‘you’ve saved that guy’s life like’…if it wasn’t for you, you really did, saved his life, well done’…I got the big heid after that, you know?.. There’s him telling me I could do his job.” (p50)

Another respondent had similar thoughts:

R: they [paramedics] said I had done perfect. I done everything perfect. I done everything right.

I: And how did you feel when the ambulance gave you that feedback?

R: Quite chuffed, aye I was quite chuffed that, I’d done something right ..I’ve actually done something that’s helped somebody that’s saved his life. I felt, really good about myself cause sometimes lately I’ve been feeling pretty shit…And now, I’m quite confident enough to go and help them like that [clicks fingers]. Without a shadow of a doubt I’d be able to do everything. (p50-51)9

Interestingly, the included studies also indicate that peer users’ own attitudes and behaviours towards drug use could be altered after using naloxone on a peer and could lead to a commitment to practice harm reduction.9

Burnout

Another emotional response described is one of emotional exhaustion and burnout. Peer responders who were called on to intervene frequently in the event of an overdose spoke of the subsequent emotional stress and trauma that they experienced. A study based out of Toronto, Canada explored the experience of PWUD who are employed by a community health centre to operate satellite harm reduction programs within their homes. Because of their role as “’go-to’ people in their communities with access to harm reduction supplies and training, SSW [these workers] are frequently intervening in drug-related emergency situations” (p131).10 Their primary role is to distribute and dispose of harm reduction equipment; however, many satellite sites allow clients to inject drugs on site.10 The findings from this study indicate that many of these PWUD were emotionally exhausted from their role.

One factor which appeared to contribute to emotional stress and trauma was the increasing frequency of overdose events. In a study conducted in China, users attributed the increase in overdoses to situations when heroin was mixed with other injectable drugs, such as with diazepans and antihistamine medications.20 In the Canadian study, however, peer responders attributed this increase in overdose events to the increased contamination of the drug supply with fentanyl and fentanyl-analogues:10 “Like, I’ve had three ODs in one week, like, give me a f*g break. You know? I’m exhausted after, right? It’s like emotionally, you’re exhausted…I’m stressed now” (p130).10

Peer responders suggested that increasing the number of safe injection sites, and diverting people away from the illicit drug supply towards safer, regulated drugs could aid in reducing the number of overdose deaths.10

The emotional burden and trauma could be exacerbated because of the closeness of the overdose victim to the responder. In some cases, the overdose victims were friends or family.10,19 One satellite worker recounted her experience when she received a call about a nephew who had overdosed at a friend’s house. She recounts her emotional state as she took the naloxone to the overdose scene:

I was so scared! As soon as I heard that on the phone, that he was down (overdosing), I just took off running. It’s so scary, especially when it’s your own family! As I was running there, I just kept thinking, ‘oh my god, am I going to make it…on time?…And since then, I’m having a bit of a hard time, you know? I can’t stop thinking about what would have happened if…if I didn’t make it in time. (p131)10

Altered Interpersonal Relations

Some participants reported negative reactions from those that they were attempting to help, which could include verbal and physical abuse. The reasons for these negative reactions were varied and included the onset of acute withdrawal, being robbed of their high, being upset that they were interrupted from a suicide attempt, and lack of awareness of fatal overdose risk.9,11 For example, “I watched a mate of mine give somebody some [naloxone] and got punched in the nose for it…I’ve never seen someone come round so quick in my life. Instant. Whack ‘What was he doing”…all that stuff” (p60).11

Some participants described how friendships had ended after the administration of naloxone.9 At times, the experienced negative reactions could also lead to resentment on the part of the person who tried to save someone’s life: “The guy didn’t say thanks, you know. And, eh, they were no thanks. He was like. ‘great, now my stone’s away. I’m bloody rattling’ and all this. I was like…you know, kinda pissed me off a bit” (p49).9

In contrast to these accounts, there were also participants who described that their naloxone intervention had been appreciated by their friend and had strengthened their relationship. For instance, one participant recounted:

…I mean he ended up coming back and apologised, he’s saying ‘look I’m sorry I, the way I reacted as obviously I knew, realised that if you hadn’t done that I wouldn’t have been here basically to thank you’…I think he was quite happy basically as I say he’s now back with his Mrs and that and his children. (p49)9

Limitations

This review is limited by the scope of the included literature. For example, while a substantial body of literature was identified describing the experiences of PWUD with naloxone administration, there was little research that described the experiences of first responders. Two articles explored the experiences of police officers,14,18 although provided no details about how they performed their tasks or of their emotional state. Firefighters were likewise underrepresented in this review. One article explored the experiences of emergency responders, including firefighters;14 however, given that some jurisdictions in Canada have trained and equipped firefighters in the administration of naloxone22 this may be an important population to study in the future.

Through the body of identified literature, we were unable to explore whether and how experiences may differ depending on the mode of naloxone administration (e.g., intramuscular vs. nasal). It is possible that responders experienced nasal administration as more straightforward than intramuscular, although the included studies do not allow for an in-depth analysis. Police officers in one study described the intranasal administration of naloxone as relatively simple,18 and EMS workers were noted as identifying fear of a needle stick injury,14 discomfort and fear of using intramuscular naloxone correctly in some cases.11

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

This review presents a thematic analysis of the results of 11 included studies and reveals both the promise and challenges of administering naloxone in the home and community setting. The research presented indicates that administration of naloxone in the community setting, such as through PWUDs and police officers, as well as paramedics, is feasible and viewed positively by these community members. Those who had administered naloxone noted that this could be a highly rewarding activity. Peer responders are generally proximal in terms of social setting and time, and therefore well positioned to administer naloxone, with adequate training. Police officers are also well positioned, as they explained that they often arrive at the overdose site before paramedics.

For peer responders, the administration of naloxone is described as just one step in the rescue effort. It first requires the peer to recognize an overdose event, which may not be straightforward as opioid users may choose to inject in private, or it may be difficult to distinguish between an overdose event and a, perhaps intentional, deep level of intoxication. Next, the peer responder must seek out their naloxone kit, which might not be near them and which may introduce delays to the rescue effort. Community members who are trained to administer naloxone are trained to call 911 as part of the rescue effort; however, the decision to actually call 911 can be difficult for peers as this can introduce fears of prosecution, or jeopardize the housing status of both the user or the naloxone administrator, because many housing units prohibit the use of illicit drugs. Finally, is the administration of naloxone. Generally, peer responders reported feeling capable of administering naloxone; however, those who were less experienced expressed uncertainty about the amount of naloxone to administer and when it should be re-administered. Those who had received some training in the administration of naloxone, but who had yet to use it in an overdose event, may require retraining.

The administration of naloxone can send the overdose victim into sudden, difficult withdrawal, which is experienced as extremely painful for the overdose victim and can lead to an abusive and violent encounter with the naloxone administrator. In response to this challenge, the studies indicate that through experience, EMS participants and peer responders learned how to titrate doses when reviving opioid drug users,14 so that the patient recovered breathing but avoided being sent into immediate withdrawal.14–16 This strategy was felt to avoid a potentially violent encounter with the opioid victim, while still providing lifesaving treatment. Titrating doses may also be desirable for the overdose victim as it can reduce withdrawal symptoms and therefore reduce the desire for the victim to immediately return to opioid use. The difficulty of dealing with a patient who is coming out of withdrawal should be emphasized in training for naloxone administration. The possibility of titrating doses, which may occur particularly with experience should be discussed. One study found that responders thought that titrating may require a combination of training and resources, such as a combination of intranasally and intramuscularly or intravenously administered naloxone.14

The administration of naloxone was described as an emotional experience across responder groups. Initial feelings of fear and panic were noted among peer responders, particularly when describing their first encounter with an overdose. These feelings gave way to feelings of pride and elation when the attempt to administer naloxone was successful and the patient was revived. Peer responders who received praise for their intervention from first responders were particularly proud, which contributed to their sense of competency and willingness to intervene in future events. Some observers have pointed out that the administration of naloxone is particularly beneficial for the peer responder, as it encourages pro-social behaviour, and can lead the responder to engage in their own harm reduction activities. Educational strategies that included such messaging may help inform first responders that positive interactions with the peer responder can have a very positive effect, beyond the isolated experience of administering naloxone. Furthermore, to acquire an understanding that due to their precarious position as users of illicit substances, even calling 911 for peer responders can constitute a heroic act, given the possibility of negative repercussions (e.g., loss of housing).

Feelings of pride were similarly described among EMS workers, and police officers. Police officers noted that administering naloxone was a useful and meaningful component of their role, because often they arrive at the scene before EMS workers. They also noted that it could be more rewarding than some of their other tasks, because they could see the effect of their actions, which is not typically the case. In addition, some police officers suggested that naloxone administration could lead to improved community relationships because they were observed to help, rather than arrest, people.

EMS workers and peer responders who responded to frequent overdose events reported feelings of emotional exhaustion and burnout. For EMS workers this appears related to the perspective of some that their intervention may be relatively futile, since they may see the same person again, and their perception that the person does not really want to be saved because the opioid was self-administered. The accounts described within the included studies suggest that some EMS workers may lack an understanding of the recovery process for opioid addiction. As suggested by Elliot,15 basic education in addiction theory and mental health issues would be desirable for emergency responders so that they understand addiction as a mental health condition rather than as a matter of individual lifestyle choice. This would aid in understanding the role of naloxone in the context of addiction as a chronic, relapsing condition,14 and to emphasize that naloxone is a harm-reduction strategy and does not treat underlying addiction.14 This sort of educational initiative could help indicate that their intervention is not futile and could lead to improved emotional states of the responders and perhaps improved interactions with the overdose victim. It is possible this could in turn have a positive impact on the victim’s subsequent interest in engaging with health care professionals.

For peer responders, emotional exhaustion and burnout emerged in relation to the nature of these overdoses occurring in their own community, with increasing frequency, and the victims may be their own friends and family. Peer responders noted that sometimes their intervention led to altered interpersonal relationships. In some cases, overdose victims were appreciative of the intervention, but other times they were not. Both EMS workers and peer responders expressed frustration that administering naloxone did not address the root cause of the opioid crisis in their communities.10,14,16 Ideally options to reduce the incidence of opioid addiction in the community should be explored. Further, programs to mitigate burnout and emotional exhaustion may prove useful for all individuals who deal with a large number of overdoses, including emergency responders and peer responders, and those who deal with overdoses that are occurring within their own communities. There have been some initiatives to implement programs to help address trauma among EMS workers, but the literature reviewed here did not uncover any examples for peer responders.10

The research indicates that an overdose event can be a pivotal moment in the lives of the opioid victim and the peer responder. Some opioid victims and some peer responders explained that they initiated harm reduction activities (e.g., attempts to cease heroin use, ceasing mixing heroin with other drugs, not taking drugs alone, initiating methadone-assisted treatment subsequent to the overdose event)9,15 suggesting an impact on people’s lives beyond the act of administering naloxone.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Pallasch

TJ, Gill

CJ. Naloxone-associated morbidity and mortality.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;52(6):602–603. [

PubMed: 7031551]

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software [computer program]. Version 11: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2014.

- 8.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 9.

McAuley

A, Munro

A, Taylor

A. “Once I’d done it once it was like writing your name”: Lived experience of take-home naloxone administration by people who inject drugs.

Int J Drug Policy. 2018;58:46–54. [

PubMed: 29803097]

- 10.

Kolla

G, Strike

C. ‘It’s too much, I’m getting really tired of it’: Overdose response and structural vulnerabilities among harm reduction workers in community settings.

Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:127–135. [

PubMed: 31590088]

- 11.

Holloway

K, Hills

R, May

T. Fatal and non-fatal overdose among opiate users in South Wales: A qualitative study of peer responses.

Int J Drug Policy. 2018;56:56–63. [

PubMed: 29605706]

- 12.

McAuley

A, Munro

A, Bird

SM, Hutchinson

SJ, Goldberg

DJ, Taylor

A. Engagement in a National Naloxone Programme among people who inject drugs.

Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:236–240. [

PMC free article: PMC5854250] [

PubMed: 26965105]

- 13.

Neale

J, Brown

C, Campbell

ANC, et al. How competent are people who use opioids at responding to overdoses? Qualitative analyses of actions and decisions taken during overdose emergencies.

Addiction. 2019;114(4):708–718. [

PMC free article: PMC6411430] [

PubMed: 30476356]

- 14.

Bessen

S, Metcalf

SA, Saunders

EC, et al. Barriers to naloxone use and acceptance among opioid users, first responders, and emergency department providers in New Hampshire, USA.

Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:144–151. [

PMC free article: PMC7153573] [

PubMed: 31590090]

- 15.

Elliott

L, Bennett

AS, Wolfson-Stofko

B. Life after opioid-involved overdose: survivor narratives and their implications for ER/ED interventions.

Addiction. 2019;114(8):1379–1386. [

PMC free article: PMC6626567] [

PubMed: 30851220]

- 16.

Kilwein

TM, Wimbish

LA, Gilbert

L, Wambeam

RA. Practices and concerns related to naloxone use among emergency medical service providers in a rural state: A mixed-method examination.

Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100872. [

PMC free article: PMC6487279] [

PubMed: 31061782]

- 17.

Lankenau

SE, Wagner

KD, Silva

K, et al. Injection drug users trained by overdose prevention programs: responses to witnessed overdoses.

J Community Health. 2013;38(1):133–141. [

PMC free article: PMC3516627] [

PubMed: 22847602]

- 18.

Wagner

KD, Bovet

LJ, Haynes

B, Joshua

A, Davidson

PJ. Training law enforcement to respond to opioid overdose with naloxone: Impact on knowledge, attitudes, and interactions with community members.

Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:22–28. [

PubMed: 27262898]

- 19.

Worthington

N, Markham Piper

T, Galea

S, Rosenthal

D. Opiate users’ knowledge about overdose prevention and naloxone in New York City: a focus group study.

Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:19. [

PMC free article: PMC1557479] [

PubMed: 16822302]

- 20.

Bartlett

N, Xin

D, Zhang

H, Huang

B. A qualitative evaluation of a peer-implemented overdose response pilot project in Gejiu, China.

Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(4):301–305. [

PubMed: 21658931]

- 21.

Bowles

JM, Lankenau

SE. “I gotta go with modern technology, so I’m gonna give ‘em the Narcan”: The diffusion of innovations and an opioid overdose prevention program.

Qual Health Res. 2019;29(3):345–356. [

PubMed: 30311841]

- 22.

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 2Characteristics of Included Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Study Objectives | Sample Size | Inclusion Criteria | Data Collection |

|---|

| Bessen, 2019, USA | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To understand respondents’ experiences with opioid use and overuse | 112 (36 responders, 76 users) | Residents of New Hampshire 18 years of age and older, and (1) recent or ongoing opioid use or (2) working as an emergency provider (EMS, firefighter or police) | Semi-structured interviews |

| Elliot, 2019, USA | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To examine interactions between survivors and medical care providers and how this may influence opioid risk behaviours post-overdoes. | 35 (9 EMS, 6 EDS, 20 overdose survivors) | Recruitment through two hospitals in Manhattan experiencing high overdose mortality rates in the borough | Semi-structured interviews |

| Kilwein, 2019, USA | Mixed (qualitative and quantitative) | To explore practices and concerns related to naloxone among EMS providers in a rural state | 20 | Recruitment from a state-wide EMS conference | Focus groups for qualitative |

| Kolla, 2019, Canada | Qualitative (community-based research approach) | To explore how structural vulnerabilities constrain peer drug users as they try to implement advice about how to respond to overdoses | 8 | People who use drugs who operate small satellite harm reduction programs within their homes | Ethnographic observation, interviews, and one focus group |

| Holloway, 2018, UK (Wales) | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To explore the responses of witnesses to peer opiate overdoses | 55 | The person was or had recently been an opiate user, and they had personally experienced or witnessed an overdose event | Semi-structured interviews |

| Neale, 2019, UK (England) | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To understand how opioid users who had recently participated in a Take-Home Naloxone program responded when confronted with an overdose emergency | 39 | Opioid user who has recently participated in a take home naloxone program and been confronted with an overdose emergency | Semi-structured interviews |

| McAuley, 2016, UK (Scotland) | Qualitative (Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis) | To understand the lived experience of take home naloxone among people who inject drugs in the UK | 8 | People who inject drugs who had used take home naloxone to reverse an overdose, within a large urban Health board in Scotland | Semi-structured interviews |

| Wagner, 2016, USA | Mixed (qualitative and quantitative) | To evaluate a pilot naloxone program for Law enforcement officers | 4 for qualitative component | Law enforcement officers who had received the training and used naloxone to respond to an overdose | For qualitative, semi-structured interviews |

| Lankenau, 2013, USA | Mixed (qualitative and quantitative) evaluation of a training program | Qualitative: To describe how participants executed key elements of SCARE ME in response to a witnessed overdose and circumstances that encouraged or inhibited recommended response behaviors.to understand why or why not the participants undertook certain behaviours in response to the overdose. To understand any negative things that happened as a result of the overdose. | 30 | ≥ 18 years of age and received overdose prevention training. Self-reported injection drug use in the past 30 days; and witnessed an overdose since receiving training and within the past 12 months. | Semi-structured interviews |

| Bartlett, 2011, China | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To explore local understandings of risk factors related to overdose, assess ongoing barriers to overdose response and solicit client input about how to reduce opiate overdose | 30 (15 who called a hotline because of the overdose of a peer) 15 who received naloxone | Those who had received a naloxone injection, or individuals who had called a hotline and were present during the administration of naloxone | Semi-structured interviews |

| Worthington, 2006, USA | Qualitative, not otherwise specified | To understand participants’ (i) experiences with overdose response, specifically naloxone (ii) understanding and perceptions of naloxone, (iii) comfort level with naloxone administration and (iv) feedback about increasing the visibility and desirability of the naloxone distribution program. | 13 | Group 1 - opiate users Group 2 - completion of overdose prevention program and receipt of naloxone | Focus groups |

EDS = Emergency Department services; EMS = Emergency Medical Services

Appendix 3. Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 3Characteristics of Study Participants

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Sample Size | Sex (% male) | Age range in years | Other relevant variable(s) |

|---|

| Bessen, 2019, USA | 112 (36 responders, 76 users) | 81% for responders 49% for users | Mean 42 (SD 10) for responders Mean 34 (SD 8) for users | Responders had administered naloxone on average (mean) 52 times (SD=107) |

| Elliot, 2019, USA | 35 (9 EMS, 6 EDS, 20 overdose survivors) | 89% for EMS 67% for EDS 80% for overdose survivors | 21-41 for EMS NR for EDS NR for overdose survivors | Years in EMS ranged from 3-21, with 11 years being the mean. |

| Kilwein, 2019, USA | 20 | 65% | NR | Years of experience=0.5-30 years; 55% paramedics, 35% EMS, 10% (firefighter, emergency room nurse) |

| Kolla, 2019, Canada | 8 | 27% | 45-70 | These people who use drugs and workers receive compensation and attend regular training sessions related to their work. |

| Holloway, 2018, UK (Wales) | 55 | 82% | 18-54 | 93% ever had treatment 78% ever been in prison |

| McAuley, 2016, UK (Scotland) | 8 | 87% | 16-54 | 100% were people who inject drugs 100% had used naloxone 86% in treatment, all had witnessed an overdose |

| Neale, 2019, UK (England) | 39 | 12% | 22-58 | 36% current injector |

| Wagner, 2016, USA | 4 | NR | NR | NR |

| Lankenau, 2013, USA | 30 | 60% | 21-59 | NR |

| Bartlett, 2011, China | 30 (15 peer responders, 15 naloxone recipients) | 80% for peer responders 73% for naloxone recipients | Mean 40 for responders Mean 37 for naloxone recipients | Responders were 33% family, 67% friend |

| Worthington, 2006, USA | 13 | 77% | NR | Participants were recruited from Overdose Prevention and Reversal Program in the Lower East Side of New York City |

EDS = Emergency Department services; EMS = Emergency Medical Services; NR = Not Reported; SD = Standard Deviation

Appendix 4. Critical Appraisal of Included Studies

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Included Studies

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Bessen, 201914 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated recruitment strategies were appropriate qualitative methodology, research design, and data collection were appropriate for aims of research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board) data analysis was appropriate for the method results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

|

| Elliot, 201915 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated recruitment strategies were appropriate qualitative methodology, research design, and data collection were appropriate for aims of research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board) results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

researchers did not critically examine their own role or discuss potential biases data analysis lacks thematic conceptual groupings sometimes there were insufficient data presented to support the claims made by the researchers

|

| Kilwein, 201916 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated recruitment strategies were appropriate qualitative methodology, and research design, were appropriate for aims of research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board) results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

researchers did not critically examine their own role or discuss potential biases data collection was based on questions that are a bit narrow for qualitative research (e.g. “Have you used naloxone? What type of training did you receive?”). (p.2) For this reason, the findings are a bit thin.

|

| Kolla, 201910 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board) results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights relationship between researcher and participants is described good theoretical analysis of the relationship between experiences and broader structural forces (political context)

|

|

| Holloway, 201811 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board) data analysis was appropriate for the method results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

|

| McAuley, 20189 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board theoretical orientation was specified (phenomenology) data analysis and statement of findings was clear data analysis was iterative and inductive limitations were addressed

|

|

| Neale, 201913 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board data analysis and statement of findings was clear data analysis was iterative and inductive limitations were addressed

|

|

| Wagner, 201618 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board

|

|

| Lankenau, 201317 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

|

| Bartlett, 201120 |

|---|

aims of research were clearly stated. qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

relationship between researcher and participants was not considered not theoretical (yet research question is not theoretical) quotes were very infrequently used in the text therefore the descriptions in the text are not well substantiated.

|

| Worthington, 200619 |

|---|

aims of research are clearly stated qualitative methodology, research design, data collection, and recruitment strategy were appropriate for the aims of the research ethical considerations were adequately addressed (review by an ethical review board results are clearly reported and offer some useful insights

|

|

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Administration of Naloxone in a Home or Community Setting: A Rapid Qualitative Review. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Dec. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Health Canada, Canada’s provincial or territorial governments, other CADTH funders, or any third-party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.