From: Chapter 27, Deuterostomes

PDF files are not available for download.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

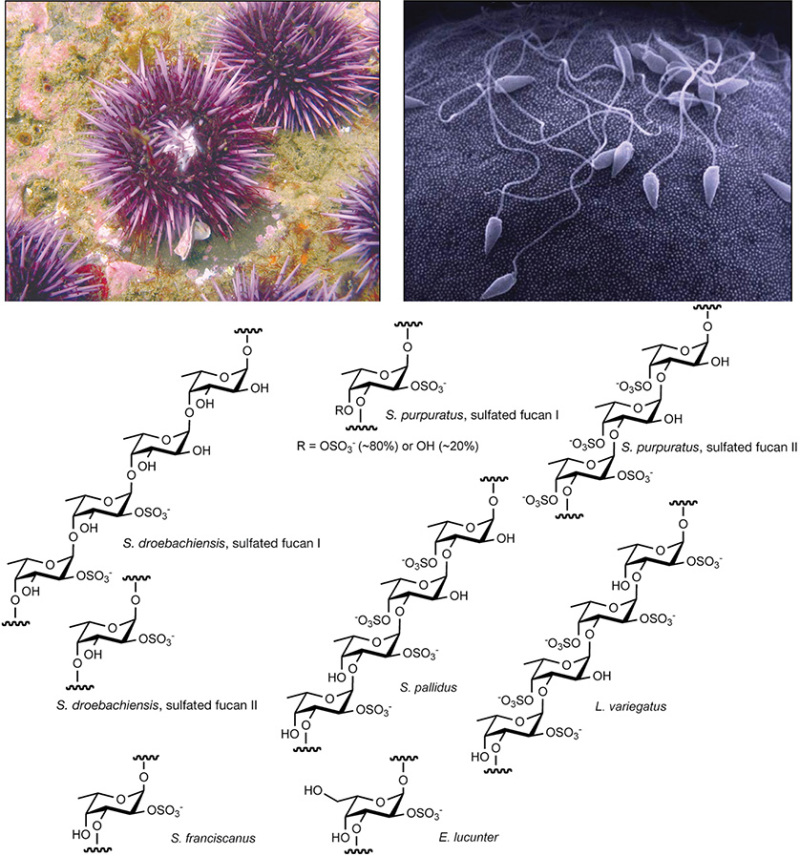

(Top left) The purple sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. (Reprinted, with permission, courtesy of Charles Hollahan, Santa Barbara Marine Biologicals.) (Top right) Sperm binding to a sea urchin egg. (Reprinted, with permission, courtesy of M. Tegner and D. Epel.) Many of the key discoveries regarding glycans and their role in determining species-specific sperm–egg binding and blocks to polyspermy were made in sea urchins. (Bottom) Structures of sulfated α-fucans and a sulfated α-galactan (marked as Echinometra lucunter) from sea urchin egg jelly are shown. The specific pattern of sulfation, the position of the glycosidic linkage, and the constituent monosaccharide vary among sulfated polysaccharides from different species. These structures were deduced from analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. (Redrawn, with permission, from Vilela-Silva AC, et al. 2002. J Biol Chem 277: 379–387, © American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.)

Download Teaching Slide (PPTX, 2.3M)

From: Chapter 27, Deuterostomes

PDF files are not available for download.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.