NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Forman-Hoffman V, Middleton JC, Feltner C, et al. Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review Update [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 May. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 207.)

Introduction

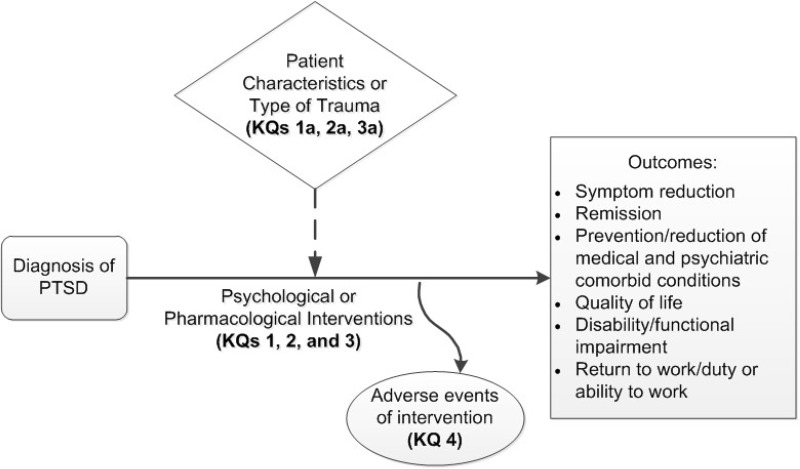

This systematic review uses current methods to update a report published in 2013 that evaluated psychological and pharmacological treatments of adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This review focuses on updating the earlier work, expanding the range of treatments examined, addressing earlier uncertainties, identifying ways to improve care for PTSD patients, and reducing variation in existing treatment guidelines. Treatments examined are shown in Table A. The analytic framework that guides our review is shown in Figure A.

Results/Key Findings

- We used information from 207 published articles reporting on 193 studies to answer our Key Questions (KQs).

- KQ 1 (Psychological Treatment) Findings (Table B)

- –

Two types of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) treatments had high strength of evidence (SOE) of benefit in reducing PTSD-related outcomes. These treatments included CBT-exposure and CBT-mixed treatments (CBT-mixed was a term we used to combine CBT treatments that had different types of CBT characteristics).

- –

Other psychological treatments with moderate SOE of benefit included cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and narrative exposure therapy (NET).

- –

Moderate strength of evidence favored CBT-exposure over relaxation for reducing PTSD-related outcomes.

- KQ 3 (Psychological Versus Pharmacological Treatment) Findings

- –

Insufficient evidence from a single study examined the comparative effectiveness of a psychological and pharmacological treatment.

- KQ 4 (Adverse Events of Treatments)

- –

Most studies did not describe methods used to systematically assess adverse event information.

- –

Insufficient evidence was found for all serious adverse event comparisons between and across psychological and pharmacological treatments.

- –

When looking at the treatments with at least moderate SOE of benefit, the only adverse event found to have at least moderate SOE was nausea, with venlafaxine.

- Contextual Question (CQ) 1a (Components of Efficacious Interventions)

- –

One study determined that the most frequently identified components of efficacious PTSD psychological interventions include psychoeducation, coping skills and emotion regulation, cognitive processing and restructuring (i.e., “meaning making”), imaginal exposure, emotions, and memory processing.

- CQ 1b (Fidelity of Efficacious Treatments When Implemented in Clinical Practice Settings)

- –

No identified studies tested the degree of fidelity of psychological interventions found to be effective in study settings when implemented in clinical practice settings.

Discussion/Findings in Context: What Does the Review Add to What Is Already Known?

Our review found high SOE of efficacy for CBT-exposure and CBT-mixed treatments and moderate SOE of efficacy for CPT, CT, EMDR, and NET. Among pharmacotherapies, we found moderate SOE of efficacy for fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine. Few studies compared treatments with each other, including psychological versus pharmacological treatments, although moderate SOE favors CBT-exposure over relaxation for reduction in PTSD-related outcomes. We did not find sufficient information to comment on whether patients with different types of trauma exposure or other characteristics benefited from a particular type of treatment. For the most part, we found insufficient information about adverse events; insufficient evidence for serious adverse events was found for all of the treatments examined.

Our findings are similar to existing guidelines and systematic reviews that have shown that some psychological therapies and some pharmacological treatments are effective treatments for adults with PTSD. The recently published American Psychological Association (APA) review found evidence to strongly recommend CPT, CT, CBT, prolonged exposure (PE), and to, a slightly lesser degree, recommend EMDR, NET, and brief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP).87 Each of these psychological treatments had at least moderate or high strength of evidence of efficacy to reduce PTSD symptoms in this updated review, with the single exception of BEP having insufficient strength of evidence for reduction in PTSD symptoms and low strength of evidence for both loss of PTSD diagnosis and reduction in depression symptoms. The APA group also recommended fluoxetine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and sertraline, the same four medications recommended in the Department of Defense/Veterans Administration guidelines;88 this updated review found moderate strength of evidence in support for fluoxetine, paroxetine, venlafaxine as well, with the exception of limited evidence for sertraline (low SOE), driven by heterogeneity in individual study findings.

For the most part, the conclusions made in this update remain unchanged from our prior review published in 2013 on this topic.89 Additional evidence prompted the increase of a few of the SOE grades for psychological treatments (e.g., CBT-mixed from moderate to high for reduction in PTSD symptoms, loss of PTSD diagnosis, and reduction in depression symptoms; CBT-exposure from moderate to high for loss of PTSD diagnosis; and EMDR from low to moderate for reduction in PTSD symptoms). Conversely, some of the SOE grades decreased from the last review for some of the pharmacological treatments after reassessing the SOE (fluoxetine from moderate to low for no difference for reduction in depression symptoms, sertraline from moderate to low for reduction in PTSD symptoms and from low [for benefit] to low for no difference for reduction in depression symptoms, and topiramate from moderate to low for reduction in PTSD symptoms), although the SOE changed from insufficient to moderate for loss of PTSD diagnosis and low to moderate for reduction in depression symptoms for venlafaxine (reduction in PTSD symptoms remained at moderate). The SOE moved from insufficient to low for reduction in PTSD symptoms for four treatments—trauma affect regulation (TAR), imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT), prazosin, and olanzapine. Consistent with the prior review, the evidence included in this update yielded mostly insufficient evidence regarding comparative effectiveness and harms associated with treatments of interest. Finally, our searches yielded no evidence of studies that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria that tested any of the newly added treatment types (energy psychology/emotional freedom techniques, and the three atypical antipsychotics, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, and quetiapine).

Despite evidence of benefit of several types of psychological and pharmacological treatments for PTSD, however, clinicians still are uncertain about which treatment to select for individual patients. Our findings suggest that clinicians might need to consider other factors in selecting a treatment for PTSD: patient preference of treatment, whether the patient has care available to them, whether they can afford the treatment, whether they have tried any treatments already, or whether the patient has other co-occurring problems like substance use or depression.

Key Limitations and Research Gaps

Key limitations include the following.

- We did not find studies that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria and studied the efficacy or effectiveness of several types of PTSD treatments such as energy psychology, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, tricyclic antidepressants, other second generation antidepressants, newer antipsychotics (e.g., ziprasidone, aripiprazole and quetiapine), benzodiazepines, and other medications such as naltrexone, cycloserine, and inositol. Of note, none of these interventions are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat PTSD.

- We did not find many studies of comparative effectiveness that directly compared the benefits of two types of treatments.

- Few studies examined whether particular treatments are better or worse for particular kinds of patients.

- Few studies provided information about adverse events associated with PTSD treatments.

Research gaps include the following.

- Comparing psychological and pharmacological treatments with known benefits in reducing PTSD-related outcomes with each other.

- Examining benefits associated with new PTSD treatments and also the currently used treatments (e.g., energy psychology, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, tricyclic antidepressants, other second generation antidepressants).

- Determining whether certain treatments work better or worse for particular types of patients.

- Designing studies to search and record adverse events for patients enrolled in research studies.

A summary of the review is presented in Table D.

Important Studies Underway

One trial of mirtazapine (https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00302107) and one trial of mindfulness based stress reduction (https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01532999) described as completed in clinicaltrials.gov but findings not yet published.

Footnotes

NOTE: The references for the Evidence Summary are included in the reference list that follows the appendixes.

Figures

Tables

Table APsychological and pharmacological interventions used for treatment of patients with PTSD

| Psychological Interventions | Pharmacological Interventions |

|---|---|

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing Other psychological or behavioral therapies

Energy psychology | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors:

Selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors:

Tricyclic antidepressants:

Other second-generation antidepressants:

Alpha blockers:

Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics:

Anticonvulsants (mood stabilizers):

Benzodiazepines:

Other medications: Naltrexone, cycloserine, and inositol |

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Bold: newly included treatment type examined in this updated review.

Table BSummary of efficacy and strength of evidence of PTSD psychological treatments

| Treatment | Symptom | N Trials (Subjects) | Findings | SOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) | PTSD Symptomsa | 5 (399)1 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −1.35 (95% CI, −1.77 to −0.94) | Moderate |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 4 (299)1–4 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD 0.44 (95% CI, 0.26 to 0.62) | Moderate | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 5 (399)1–6 | Reduced depression symptoms SMD −1.09 (95% CI, −1.52 to −0.65) | Moderate | |

| Cognitive therapy (CT) | PTSD Symptomsa | 4 (283)5, 7–9 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD of individual studies ranged from −2.0 to −0.3 All studies favored treatment (All studies p<0.05) | Moderate |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 4 (283)5, 7–9 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD 0.55 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.82) All studies favored treatment (3 of 4 studies p<0.05) | Moderate | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 4 (283)5, 7–9 | Reduced depression symptoms Between-group mean differences of individual trials ranged from −11.1 to −8.3 All studies favored treatment (4 of 4 studies p<0.05) | Moderate | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy-exposure (CBT-exposure) | PTSD Symptomsa | 13 (885)3,

10–21 8 (689)3, 10, 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, 21 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −1.23 (95% CI, −1.50 to −0.97) SMD CAPS −1.12 (95% CI, −1.42 to −0.82) | High |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 6 (409)3, 13, 14, 16, 17, 21 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD 0.56 (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.78) | Highc | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 10 (715)3, 11–15, 18–21 | Reduced depression symptoms SMD −0.76 (95% CI, −0.91 to ‑0.60) | High | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy-mixed (CBT-mixed) | PTSD Symptomsa | 21 (1,349)12,

14,

22–40 11 (709)22, 23, 27–29, 34–39 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −1.01 (95% CI, −1.28 to −0.74) SMD −1.24 (95% CI, −1.67 to −0.81) | Highc |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 9 (474)22–24, 31–34, 39, 41 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.40) | Highc | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 15 (929)12, 14, 22–24, 28, 29, 33, 35–40, 42 | Reduced depression symptoms SMD −0.87 (95% CI, −1.14 to −0.61) | Highc | |

| Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) | PTSD Symptomsa | 8 (449)13, 16, 43–48 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −1.08 (95% CI, −1.82 to −0.35) | Moderated |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 7 (427)13, 16, 43–45, 47, 48 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD 0.43 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.61) | Moderate | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 7 (347)13, 43–48 | Reduced depression symptoms SMD −0.91 (95% CI, −1.58 to ‑0.24) | Moderate | |

| Brief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP) | Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 3 (96)49–51 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD of individual studies ranged 0.13 to 0.58 All studies favored treatment (p<0.05) | Low |

| Depression Symptomsb | 3 (96)49–51 | Reduced depression symptoms Different depression scales used; all 3 studies favored treatment (3 of 3 studies p<0.05) | Low | |

| Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) | PTSD Symptomsa | 1 (168)52 | Reduced PTSD symptoms Between-group mean difference −21.0; p<0.05 | Low |

| Narrative exposure therapy (NET) | PTSD Symptomsa | 3 (232)53–55 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD ranged from −1.95 to −0.79 across 3 individual studies (3 of 3 studies p<0.05) | Moderate |

| Loss of PTSD Diagnosis | 2 (198)53, 54 | Greater loss of PTSD diagnosis RD of 0.06 and 0.43 in individual studies Both studies favored treatment (1 of 2 studies p<0.05) | Low | |

| Seeking Safety (SS) | PTSD Symptomsa | 3 (232)56–58 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD of individual trials ranged from −0.22 to 0.04 Two of three trials favored treatment (0 of 3 studies p<0.05) | Low for no difference |

| Trauma affect regulation (TAR) | PTSD Symptomsa | 2 (173)59, 60 | Reduced PTSD symptoms Between-group mean difference of −17.4 and −2.7 in individual studies Both favored treatment (1 of 2 studies p<0.05) | Low |

NOTE: Outcomes graded as insufficient are not included in this table.

- a

SMD from the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale and other various PTSD symptom scales.

- b

SMD from the Beck Depression Inventory and other various depression symptom scales.

- c

Strength of evidence increased from moderate to high because of additional evidence of efficacy published since prior PTSD review

- d

Strength of evidence increased from low to moderate because of additional evidence of efficacy published since prior PTSD review

CI = confidence interval; N = number of subjects; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RD = risk difference; SMD = standardized mean difference; SOE = strength of evidence.

Table CSummary of efficacy and strength of evidence of PTSD pharmacological treatments

| Treatment | Symptom | N Trials (Subjects) | Findings | SOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine (SSRI) | PTSD Symptomsa | 4 (835)47, 61–63 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −0.28 (95% CI −0.42 to −0.14) | Moderate |

| Depression Symptomsb | 3 (771)47, 61, 62 | Similar reduction in depression symptoms SMD −0.20 (95% CI −0.40 to 0.00) | Low for no differencec | |

| Paroxetine (SSRI) | PTSD Symptomsa | 2 (348)64, 65 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD of −0.56 to −0.44 in individual studies Both studies favored treatment (2 of 2 studies p<0.05) | Moderate |

| PTSD Symptom Remission | 2 (348)64, 65 | Greater PTSD symptom reduction RD of 0.13 and 0.19 across 2 individual studies (1 of 2 studies p<0.05) | Moderate | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 2 (348)64, 65 | Reduced depression symptoms SMD ranged from −0.60 to ‑0.34 across individual studies Both studies favored treatment (2 of 2 studies p<0.05) | Moderate | |

| Sertraline (SSRI) | PTSD Symptomsa | 7 (1,085)66–72 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −0.20 (95% CI: −0.36 to −0.04) | Lowd |

| Depression Symptomsb | 7 (1,085)66–72 | Similar reduction in depression symptoms SMD −0.14 (95% CI: −0.33 to 0.06) | Low for no differencee | |

| Venlafaxine (SNRI) | PTSD Symptomsa | 2 (687)69, 73 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD of −0.35 and −0.26 for two individual studies | Moderate |

| PTSD Symptom Remission | 2 (687)69, 73 | Greater PTSD symptom remission RD of 0.12 and 0.15 across individual studies | Moderatef | |

| Depression Symptomsb | 2 (687)69, 73 | Reduced depression symptoms Between-group mean difference of −2.6 and ‑1.6 across individual studies | Moderateg | |

| Prazosin (alpha blocker) | PTSD Symptomsa | 3 (117)74–76 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −0.52 (95% CI, −0.90 to −0.14) | Low |

| Topiramate (anticonvulsant) | PTSD Symptomsa | 3 (142)77–79 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD ranged from −1.85 to −0.38 across individual studies | Lowh |

| Olanzapine (antipsychotic) | PTSD Symptomsa | 2 (47)80,

81 3 (62)80–82 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD of −1.15 and −0.96 across individual studies,80, 81 both significantly favored treatment, N=47 SMD ranged from −1.15 to 0.89 across individual studies All studies favored treatment (2 of 3 studies p<0.05) | Low |

| Risperidone (antipsychotic) | PTSD Symptomsa | 4 (422)83–86 | Reduced PTSD symptoms SMD −0.26 (95% CI, −0.52 to −0.01) | Low |

NOTE: Outcomes graded as insufficient are not included in this table. Insufficient evidence was provided for divalproex (anticonvulsant), tiagabine (anticonvulsant), citalopram (SSRI), all TCAs, buproprion (other second-generation antidepressant [SGA]) and mirtazapine (other SGA). No studies that met inclusion criteria rated as having low or medium risk of bias evaluated lamotrigine (anticonvulsant), any benzodiazepine, desvenlafaxine (SNRI), duloxetine (SNRI), nefazodone (other SGA), or trazodone (other SGA).

- a

SMD from Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale or from various other PTSD symptom scales.

- b

SMD from the Beck Depression Inventory or from various other depression symptom scales.

- c

Strength of evidence changed from moderate in the prior review to low for no difference in the updated review. Only 2 of 3 studies favored treatment, one favored placebo. Imprecision, inconsistency, and effect sizes near the null prompted the change in grade.

- d

Strength of evidence changed from moderate in the prior review to low in the updated review. The studies were inconsistent in whether findings favored treatment or the inactive comparator group and findings were imprecise.

- e

Strength of evidence changed from low to low for no difference in the updated review. The studies were inconsistent in whether findings favored treatment or the inactive comparator group, findings were imprecise, and most individual study estimates were close to the null.

- f

Strength of evidence changed from insufficient to moderate in the updated review because of consistent evidence across two studies of adequate sample sizes.

- g

Strength of evidence changed from low to moderate in the updated review because of consistent evidence across two studies of adequate sample sizes.

- h

Strength of evidence changed from moderate in the prior review to low in the updated review. The findings were imprecise, only 1 of 3 individual studies found significant differences between study groups, and the sample sizes were small.

CI = confidence interval; N = number; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RD = risk difference; SGA = second-generation antidepressant; SMD = standardized mean difference; SNRI = serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SOE = strength of evidence; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant

Table DSummary of review characteristics

| Characteristics | Criteria | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Population Included in the Review | Key Inclusion Criteria | Adults ≥18 years of age with PTSD based on any DSM criteria, RCT study designs (or SRs to search references), or non-RCTs with at least 500 subjects for the adverse event KQ (#4) |

| Key Exclusion Criteria | Studies with participants <18 years of age, studies without RCT study designs, or studies without at least 500 subjects for KQ4. | |

| Key Topics & Interventions Covered by Review | Key Topics | Interventions |

| 1. Benefits of psychological treatments; variation in benefits by trauma or other patient characteristics | Brief eclectic psychotherapy, CBT including cognitive restructuring, cognitive processing therapy, exposure-based therapy, coping skills therapy (e.g., stress inoculation therapy, structured approach therapy, relaxation training), psychodynamic therapy, EMDR, interpersonal therapy (IPT), hypnosis or hypnotherapy, neurofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and energy psychology (including EFT) compared with each other or to an inactive treatment group. | |

| 2. Benefits of pharmacological treatments; variation in benefits by trauma or other patient characteristics | Pharmacological interventions: SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline), SNRIs (desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine), tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine, amitriptyline, and desipramine), other second-generation antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and trazodone), alpha blockers (prazosin), atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, and quetiapine), benzodiazepines (alprazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, and clonazepam), anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers (topiramate, tiagabine, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and divalproex) compared to each other or to an inactive treatment group (e.g., placebo). | |

| 3. Comparative benefits of psychological versus pharmacological treatments; variation in benefits by trauma or other patient characteristics | One of the psychological treatments compared with one of the pharmacological treatments of interest. | |

| 4. Adverse events associated with treatments | Any of the psychological or pharmacological treatments of interest. | |

| Timing of the Review | Beginning Search Date | May 2012 for treatments included in prior review. No beginning date for treatments newly added to current review. |

| End Search Date | September 29, 2017 |