Reviewers

External Reviewers

This document was externally reviewed by content experts and the following individuals granted permission to be cited.

Brian Bressler MD, MS, FRCPC

Founder, The IBD Centre of BC

Director, Advanced IBD Training Program Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of British Columbia

Abbreviations

- ASA

Aminosalicylate

- AZA

Azathioprine

- CDAI

Crohn’s Disease Activity Index

- CDEIS

Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity

- CI

Confidence interval

- HBI

Harvey-Bradshaw Index

- HR

Hazard ratio

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RR

Relative risk

- SD

Standard deviation

- SES-CD

Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease

- TNF

Tumor Necrosis Factor

Context and Policy Issues

Crohn’s disease is a chronic relapsing inflammatory condition, which primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract.1 The disease is characterized by both clinical symptoms and objective findings from endoscopy and pathology studies.1 Common symptoms include diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, and fever.2 Endoscopic findings include ulcers, inflammation, and lesions.1 The onset is typically between age 20 and 30 years, though there is a second small peak in incidence around age 50; the disease may also present in childhood or adolescence.1,3 There are three phenotypes of disease: inflammatory, structuring, and penetrating, and patients can have one or more of these phenotypes.3

The incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease is increasing worldwide, and Canada has a prevalence among the highest in the world.4 The incidence in Canada was reported as 20.2 per 100,000 persons in a 2012 systematic review.5 A 2018 report suggested that the incidence varies by province, from 8.8 per 100,000 in British Columbia to 22.6 per 100,000 in Nova Scotia.4 The prevalence was estimated at 725 per 100,000 in Canada in 2018.4 A 2011 systematic review of international studies reported that 4 per 100,000 develop Crohn’s disease in childhood or adolescence.6

People with Crohn’s disease generally experience remissions and relapses over time.3 There may also be complications such as strictures or fistulas throughout the disease course.2 People with Crohn’s disease may require bowel resection surgery at some point to manage their disease.3 Further, those with Crohn’s disease often experience regular hospital admissions. The annual incidence in hospital admission is 20%, while around 50% of patients require surgery in the 10 years after diagnosis.1 Thus, health resource utilization related to Crohn’s disease may be high.

The main goals of medical treatment are to achieve both clinical and endoscopic remission (e.g., mucosal healing), with the aim of preventing complications and surgery.1,3 Medical management, in persons with early disease or a flare, aims to achieve rapid symptom relief and long-term disease control.2 Rapid symptom relief may be achieved using a corticosteroid or a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (anti-TNF or “biologic”, e.g., infliximab).2 Maintenance of remission is often achieved with an immunomodulator (immunosuppressant) such as azathioprine (AZA) or methotrexate and/or an anti-TNF.2 The exact choice of agents and treatment approach depends on the phenotype, disease activity, severity, and individual patient characteristics.1–3 Two possible approaches are the conventional (or “step-up”) approach and early biologic (“top-down”) approach.

Traditionally, a “step-up” approach has been used, where treatment begins with a corticosteroid.7 If a person does not respond to this treatment, an immunomodulator could then be added.7 If the person is still refractory to treatment, an anti-TNF can then be added.7 Two reviews7,8 have suggested that the rationale for this approach is centered on using relatively safer (i.e. lower risk of adverse drug effects) but less efficacious options early in therapy and proceeding to more efficacious but less safe options if a patient is refractory to treatment. Lower cost has also been suggested as a rationale for the step-up approach.8 One possible challenge is that the step-up approach still results in high rates of surgical intervention.7 Corticosteroids may produce clinical remission but not affect mucosal healing.9 While using corticosteroids, inflammation may persist and result in tissue damage and disease progression.9 Mucosal healing has been noted to be particularly important in Crohn’s disease, as it can change the course of the disease.10 It is argued that step-up treatment can delay initiation of treatment that induces mucosal healing.9 The “top-down” approach involves early initiation of anti-TNF agents (with or without immunomodulators).7 When anti-TNF agents are given with immunomodulators, this may be called an “early combined” treatment approach. The theory behind top-down treatment is that it may induce mucosal healing early and subsequently may reduce the risk of downstream negative outcomes (e.g., surgery, relapse, hospitalization).9 It also appears to have positive effects on clinical outcomes. For example, the SONIC trial found that infliximab alone, or in combination with an immunosuppressant, improved rates of clinical remission at 26 weeks in treatment naïve adults.11

As mentioned, the appropriateness of these individual approaches likely depends on the severity and phenotype of disease, along with the clinical characteristics of the patient.7 Given the theorized benefits of a top-down approach (early use of biologics), there is growing interest in its clinical effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness compared to a conventional treatment approach, both in children and adults.7,8 As such, this report sought to summarize the evidence regarding the clinical and cost-effectiveness of early biologic therapy compared to conventional treatment for Crohn’s disease in children and adults.

This is an upgrade of a previous CADTH rapid response titled “Early Treatment versus Conventional Treatment for the Management of Luminal Crohn’s Disease: A Review of Comparative Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness”.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of early biologic treatment compared with conventional treatment for the management of Crohn’s disease?

What is the cost-effectiveness of early biologic treatment compared with conventional treatment for the management of Crohn’s disease?

Key Findings

The clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy compared to conventional therapy for Crohn’s disease in adults is unclear based on available evidence, due to a limited number of studies and heterogeneity of existing studies. The evidence identified in this report did not suggest consistent benefits of early biologic therapy compared to conventional treatment but did point to possible benefits which require further study.

There were six non-randomized studies conducted in children, which were limited both in terms of the size and quality. No firm conclusions can be drawn about the clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease based on current evidence.

One cost-effectiveness analysis conducted in Italy suggested that early combined therapy may be both more effective and cost-saving compared to conventional treatment for Crohn’s disease in adults.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

This project was based on a literature search performed for a previous CADTH report. A literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. No methodological filters were applied to limit by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2008 and November 22, 2018.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications or were published prior to January 1, 2008.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were appraised using Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2.0 tool.12 Non-randomized studies were appraised using Downs and Black checklist13 and economic studies were appraised using the Drummond checklist14.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

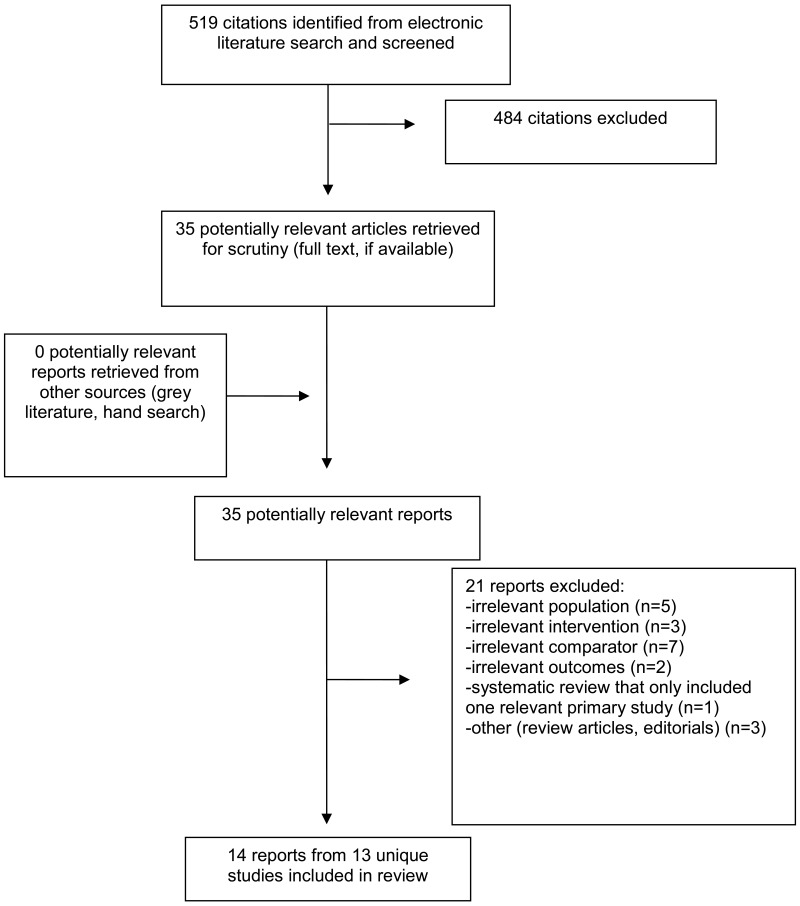

A total of 519 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 484 citations were excluded and 35 potentially relevant reports from the electronic were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of the 35 potentially relevant articles, 21 publications were excluded for various reasons and 14 publications (from 13 unique studies) met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. There were 2 RCTs (and 1 study reporting long-term follow-up from one of the RCTs) conducted in adults, 10 non-randomized studies (4 in adults and 6 in children), and 1 economic evaluation in adults. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA15 flowchart.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional detail regarding the characteristics of included studies is provided in Appendix 2. A description of scales used in the eligible studies is included at the beginning of Appendix 2.

Study Design in Adults

There were two parallel group RCTs16,17 that included adults, and one long-term follow up study of one trial.18 One (n = 1,982) was an open-label cluster randomized trial17 and one (n = 133) was an open-label randomized trial16 with long-term follow up study (n = 119 of 133 in original trial).18

There were four non-randomized studies in adults.19–22 One (n=2,662) was a prospective registry-based study20, one (n = 77) was a controlled before-after study21, one (n=93) was a retrospective chart review19, and one (n = 3,750) was a retrospective cohort study.22

There was one economic evaluation, which was a cost-effectiveness study23 using a Markov model, with a time horizon of 5 years from the perspective of the Italian healthcare system. The clinical inputs were based on an RCT16 and costs based on the Italian healthcare system. The model assumed an average weight of 60 kg, a purchase cost for infliximab of €512 and that 20% of patients having surgery would have early complications.

Study Design in Children

There were six non-randomized studies that included children.24–29 Two (n = 76 and n = 552) were prospective observational studies,27,29 two (n = 28 and n = 36) retrospective chart reviews25,26 and two (n = 29 and n = 51) retrospective observational studies.28,30

Country of Origin for Studies in Adults

One RCT was conducted in Canada and Belgium17 and one was conducted in Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany.16 The long-term follow-up study was conducted in the RCT in Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany.18 One non-randomized study used data from patients in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom,20 two were conducted in the USA,19,22 and one was conducted in China.21

Country of Origin for Studies in Children

Five studies were conducted in South Korea24–28 and one study was conducted in Canada (using data from Canada and USA).29

Patient Population in Adults

Both RCTs recruited people 18 years or older. The mean age was 44 in one trial17 and approximately 30 in the other.16 In the trial by Khanna et al., persons were included regardless of disease activity, severity or duration, or treatment history – approximately 56% were in steroid-free remission at baseline, 7% had active fistula and the mean duration of disease was around 150 months.17 In D’Haens et al., included people that were newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (mean 2 weeks from diagnosis to treatment), had clinically active disease, and were treatment naïve.16 Approximately 60% of the participants in both trials were female.

In the non-randomized studies, the median age at baseline ranged from 2521 to 40 years22 in the three studies that reported it. The other study only reported age at diagnosis, which was 28 (mean duration of disease was 11 years).19 The proportion of female participants ranged from 53 to 60%. D’Haens et al. (2017) included patients regardless of disease severity or phenotype – approximately 30% of patients had fistulas and the mean time since diagnosis was 8.5 years.20 The study by Fan et al. involved newly diagnosed persons with moderate to severe luminal disease who were treatment naïve.21 Ghazi et al. included patients regardless of severity or phenotype (48% had “penetrating” disease) and the mean duration of disease was 11 years.19 Finally, Rubin et al. did not report criteria for severity or duration.22

The economic evaluation involved a population from one of the RCTs.16 These were newly diagnosed patients (mean age 30, median disease duration 10 weeks) with active disease, who were treatment naïve.

Patient Population in Children

Two studies reported median age at diagnosis, which was 14 and 15.27,30 The other four studies reported age at study baseline which ranged between 12 and 14.25,26,28,29 The proportion of female participants ranged from 14 to 48% in the five studies24–27,29 that reported it. Kang et al. included people with newly-diagnosed moderate to severe luminal Crohn’s disease, but people in the step-up group had previously failed conventional treatment (duration of disease was 0.7 months in top-down group versus 8 months in step-up).27 Lee et al. (2015) included newly-diagnosed patients with moderate to severe disease, regardless of disease type (around 60% had fistulas; duration of disease was 1 month in top-down versus 10 months in step-up).30 Walters et al. included participants newly diagnosed with luminal Crohn’s disease regardless of severity.29 Lee et al.(2012) and Kim et al.25,28 included persons with either moderate to severe Crohn’s disease or therapy resistant disease (duration and type not specified; although in one study 62% had fistulas). Finally, the Lee et al. (2010) study included newly diagnosed persons (type and severity not specified).26

Interventions and Comparators in Adults

Khanna et al. tested an early combined immunosuppression intervention (an algorithm involving combined anti-TNF and immunomodulator treatment if persons failed a steroid induction of 4- or 12-weeks) against conventional management (described as usual care).17 In this trial, 20% of people ended up on an early combined therapy in the algorithm group compared to 10% in the conventional treatment arm. The trial by Khanna et al. differs from the other studies in included this review in that early biologic therapy was part of a treatment algorithm in this study, and the trial tested the algorithm against conventional treatment. Therefore, not all participants in the in the “early biologic” group necessarily received a biologic. In the other studies included in this review, people receiving an intervention of early biologic (or top-down) therapy were assigned that treatment from baseline (or were deemed to have received early in treatment course in the case of observational studies).

D’Haens et al. (2008) tested early combined immunosuppression (infliximab plus azathioprine) against conventional treatment (the economic evaluation used the approach from this trial).16

D’Haens et al. (2017) identified three groups from a prospective register: (1) people who started infliximab with 30 days of enrollment, (2) conventional treatment (without ever receiving anti-TNF agents, (3) conventional treatment involving switch to infliximab.20 Fan et al. tested combined treatment initiation with infliximab and AZA against initiation with corticosteroid and AZA.21 Ghazi et al. tested early biologic treatment with or without an immunomodulator against step-up treatment (immunomodulator alone or immunomodulator before anti-TNF). Finally, Rubin et al. involved three groups: (1) 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) and/or corticosteroids and/or immunomodulator prior to anti-TNF, (2) immunomodulator only prior to anti-TNF, or (3) early initiation with anti-TNF.22

Interventions and Comparators in Children

Four of the studies tested top-down treatment approaches (early infliximab plus AZA) against step-up eventually requiring infliximab (e.g. oral corticosteroid plus AZA and/or 5-ASA, then infliximab).25,27,28,30 Walters et al. identified three groups: (1) early anti-TNF without an immunomodulator, (2) early immunomodulator, and (3) no early immunotherapy.29 Lee et al. (2010) identified three groups of persons receiving: (1) prednisolone then mesalamine, (2) prednisolone then AZA, (3) infliximab plus AZA.26

Outcomes in Adults

A description of scales used in the eligible studies is included at the beginning of Appendix 2.

The primary outcome in both RCTs16,17 was remission. The proportion of patients in remission was compared between two groups. In Khanna et al, remission was defined as having a Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) less than 5 and being corticosteroid-free at 12 months.17 The proportions were compared using analysis of covariance adjusting for cluster size, country, practice size and baseline remission rate. The trial by D’Haens et al. defined remission as a Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) score of less than 150, the absence of corticosteroids and no intestinal resection at 26 and 52 weeks.16 The proportion remission in each group was compared using a χ2 test. In the long-term follow-up of the D’Haens et al. RCT, the primary outcome was also remission but this was not defined. Khanna et al. examined difference in mean HBI, time to adverse outcome (surgery, disease complication, hospital admission), time to corticosteroids, adverse events, mortality, and quality of life using 36-item short form survey (SF-36) and EuroQoL 5 dimension scale (EQ-5D).17 D’Haens et al. also evaluated the time to relapse (CDAI increase >50 to a score >200), mean CDAI and inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ), endoscopic score (4-point scale, from 0=no ulcers to 3=ulcerated stenosis, at five regions for a total score of 15) and proportion without ulcers at 24 months.16

One non-randomized study was designed to assess safety of infliximab and reported the frequency and incidence of adverse events over 5 years.20 This study reported the crude proportion of persons experiencing adverse effects and also risk of adverse events using Cox proportional hazards models. The primary outcome in Fan et al. was deep remission (CDAI < 150 plus complete absence of mucosal ulcerations).21 The proportion in deep remission was compared using a χ2 test. This study also evaluated clinical remission (not defined) and time to remission (using life-table analysis), as well as change in Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) from baseline, endoscopic response (CDEIS decrease >5), complete endoscopic remission (CDEIS <3), and adverse events (proportions were compared using χ2 test). Ghazi et al. evaluated remission (HBI<5) rate, HBI score, Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) score, number of hospitalizations, and surgeries.19 Differences between groups were analyzed using a χ2 test and t test. Finally, Rubin et al. evaluated corticosteroid use (per 6-month period) and Crohn’s disease surgery using multivariable logistic regression.22

The economic evaluation reported cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Outcomes in Children

A description of scales used in the eligible studies is included at the beginning of Appendix 2.

Four studies examined remission rate.27–30 In these studies, remission was defined as a Pediatric CDAI (PCDAI) score less than 10, and authors compared the proportion achieving remission between groups. Walters et al.29 used propensity score analysis to analyze the relative risk of remission between groups. The other three studies mention Fisher’s exact test and a χ2 test but did not specify which was used to analyze remission rates. Three studies examined relapse rate (PCDAI > 10 after remission had been achieved) – they also mention Fisher’s exact test and a χ2 test but do not specify which was used.25,26,30 Four studies reported adverse events. Two studies27,28 compared PCDAI scores between groups (Kang et al. used a t test and Kim et al. [2011] did not specify). Kim et al. (2011)28 compared rates of fistula closure between groups (Fisher’s exact test and a χ2 test mentioned but did not specify which was used). Kang et al.27 compared both mucosal healing rate (Simple Endoscopic Score [SES-CD] = 0; Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test but not specified) and endoscopic findings (SES-CD score, compared using t test) between groups.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Randomized controlled trials in adults

Details on the critical appraisal are in Appendix 3. Trials were appraised using Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2.0 tool.12 Both RCTs16,17 had concerns related to the randomization process – in Khanna et al.17 allocation concealment was not described while in D’Haens et al.,16 allocation was not concealed. Both trials were rated as low risk for deviations from intended interventions – while both were unblinded, this did not appear to introduce deviations from the intended interventions. There were some concerns related to adherence to the interventions – co-interventions were not described in either trial. In Khanna et al., one center dropped out due to non-adherence with the early combined intervention algorithm. There were some concerns in the trial by Khanna et al. related to missing data as the number of withdrawals was higher in the early combined group compared to conventional treatment (reasons for withdrawal were not specified). In both RCTs,16,17 there were concerns related to measurement of the outcome. Both trials were open label and relied and patient- and investigator-completed rating scales. Thus, it is possible that knowledge of the treatment may have influenced outcome ratings. In Khanna et al., the outcome of composite adverse outcomes was not pre-specified in the protocol, which may reduce confidence in this result. In D’Haens et al., the authors reported outcomes (remission at multiple time points) which were not in the protocol and only presented CDAI and IBDQ data at certain timepoints. The long-term follow-up study18 of the D’Haens et al trial was at high risk of bias due to selective reporting of results as this was an unplanned and post-hoc analysis. Overall, D’Haens et al. was rated at high risk of bias and Khanna et al. was rated as having some concerns.

The trial by Khanna et al.17 included persons regardless of disease duration, severity, or activity. Approximately 55% of the participants were in steroid-free remission at baseline, the mean HBI score was 4 at baseline (a score <5 suggests remission) and the mean duration of disease was over 10 years. Given the population studied, the results may apply particularly to those with less severe and longer-standing disease. Conversely, the trial by D’Haens et al.16 included people early in the disease course who were treatment naïve. Thus, these results may be most applicable to newly diagnosed persons who have not received prior treatment.

Non-randomized studies in adults

Details on critical appraisal are in Appendix 3. Critical appraisal was completed using Downs and Black checklist.13

All four non-randomized studies clearly described their aim and main outcomes. The inclusion characteristics of patients were well described in three studies;19–21 however, Rubin et al.22 included limited information on patient characteristics (e.g. disease severity, type). None of the studies included information on socioeconomic status, marital status, education or family income. Interventions were well described except by Ghazi et al.19 who included limited detail. Results were comprehensively reported by D’Haens et al.(2017); however, the other studies had some concerns surrounding reporting, reducing confidence in the results. Fan et al.21 and Ghazi et al.19 did not report differences in proportions or mean differences between groups (and variability around these measurements, e.g. standard deviation or confidence intervals), which makes it challenging to interpret results. Fan et al.21 did not include any information on missing data in their study. Neither Ghazi et al. nor Rubin et al. reported adverse events.

D’Haens et al.(2017)20 was a registry study involving around 2,000 people thus it was likely reflective of typical persons with Crohn’s disease. However, it is unclear whether the population in the other three non-randomized studies reflects the typical patient population (for example, Ghazi et al.19 was conducted at a single tertiary care center and Rubin et al.22 was conducted using a specific drug plan’s administrative claim database). This may limit the generalizability of the findings. D’Haens et al. (2017) and Rubin et al. used regression models to analyze outcomes. D’Haens et al. (2017) used a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for disease duration, severity, age and corticosteroid use, though residual confounding is possible. Rubin et al. used log binomial regression and described very limited information on confounders (sex, region, age location of disease)- it is unclear if these were adjusted for in their model. Thus, there are concerns surrounding confounding in both of these studies, limiting our confidence in the reported results. Fan et al.21 did not control for confounders in their analysis. They did show that age, sex, disease duration and severity were balanced at baseline, but residual confounding is possible in this study as well. Finally, Ghazi et al. did not adjust for confounders and their results suggest baseline imbalances and possible selection bias (e.g. patients in early biologic group were younger and had more severe disease compared to step-up patients).

Non-randomized studies in children

Details on critical appraisal are in Appendix 3. Critical appraisal was completed using Downs and Black checklist.13

All studies clearly described their aim, main outcomes, eligibility characteristics, and interventions. Three studies27,29,30 described the study population in detail; however, three of the studies included limited characteristics of the study population.25,26,28 All studies reported results of significance tests for outcomes, but three studies25,27,28 did not include information on random variability around outcome measurements comprehensively (e.g. CIs and SDs), which limits interpretability of the results. Only one non-randomized study adjusted for confounding in its analysis, the study by Walters et al. which used propensity score matching.29

For five of the studies, it is unclear whether the included persons reflect the typical patient population as they all included small samples (ranging from n = 28 to n = 76) from a single hospital.25–28,30 Further, since these studies took place at one hospital, it is unclear whether care received would reflect care at other centers. In contrast, the study by Walters et al. included data from a large observational study at 28 centers in North America, and thus likely reflects the typical patient population in Canada and the USA. There were concerns surrounding selection bias in four of the studies. In two studies26,29 patients were only included if they had one year of follow-up data available and in another study patients could only be included if they had three years of follow-up data.30 It is unclear whether systematic exclusion of patients who were not followed for the minimum time would introduce bias (e.g. if these patients tended to have worse or better outcomes this could create bias). Further, in three of the studies, people assigned to the different intervention groups may represent different populations of people with Crohn’s disease. For example, in the studies by Lee et al. (2012)25 and Kim et al.28 people assigned to the step-up group were only included after they had failed conventional therapy, while people in the top-down group were naïve to immunomodulator, anti-TNF, and corticosteroid treatment. Thus, these two groups did not represent the same population of persons at study baseline, signaling selection bias. Further, in three of the studies25,27,28 step-up patients were only included if they eventually received infliximab, which excludes the group of step-up people who did not require infliximab (also suggesting selection bias). These concerns raise the possibility that the estimates presented in these studies are biased, reducing confidence in the results. In the retrospective chart review studies,25,26,28 the procedure for identifying eligible participants was not described. It is unclear if these studies represent all persons treated with the interventions of interest or whether there was some sampling or selection procedure (and whether this was likely to have introduced bias). Five of the non-randomized studies involved small sample sizes (ranging from n = 28 to n = 76) and did not include power calculations.25–28,30 Therefore, it is unclear whether they were adequately powered to detect differences in outcomes.

Economic evaluation in adults

The economic evaluation23 clearly stated the research question, importance of the study, form of economic evaluation used, sources of data (costs, clinical data) and primary outcome. The time horizon, discount rate, and model details were provided. The discount rate was 3.5%, which is consistent with National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance.31 Incremental analysis was reported, and the outcomes are presented in aggregated and disaggregated form. The choice of variables in sensitivity analyses were not described in detail, nor were the ranges over which the variables were varied, which raises questions about the validity of the sensitivity analyses. No confidence intervals were provided for stochastic data (limiting interpretability of the data and reducing confidence in these results), and the viewpoint of the analysis was not justified.

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents a table of main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy in adults

Remission

Data on remission were available from two RCTs16,17, long-term follow-up from one RCT,18 and one non-randomized study.21 In the Khanna et al. trial17 there was no significant difference between groups for the proportion of persons in remission at 12 or 24 months. In the D’Haens et al. RCT,16 there were significantly more persons in remission at both 26 and 52 weeks for early combined therapy than conventional treatment, but no significant difference at 78 and 104 weeks. Long-term follow-up of the D’Haens trial18 over 8 years found no difference in the proportion of persons in remission over time between the two groups. Fan et al.21 reported that significantly more persons were in deep remission (clinical remission plus mucosal healing) and clinical remission at week 30 for top-down therapy versus step-up therapy, but there was no significant difference at week 54. Fan et al. also reported that the median time to clinical remission was shorter for top-down versus step-up (7 weeks versus 14 weeks).

Relapse

Relapse was reported by one RCT and long-term follow-up from that RCT. D’Haens et al.16 evaluated the time to relapse after successful induction. The authors reported that the median time to relapse was statistically significantly longer for early combined therapy versus conventional therapy (329 versus 175 days). The long-term follow up study18 from the D’Haens et al. trial found that the median time to flare was statistically significantly shorter for the conventional therapy group versus early combined and that the proportion who experienced at least one flare was higher in the conventional therapy group compared to early combined therapy.

Disease activity scores

Disease activity scores were reported by both RCTs16,17 and one non-randomized study.19 Khanna et al.17 found no difference in HBI score between groups at 6, 18, or 24 months. D’Haens et al.16 found the mean reduction in CDAI score at 10 weeks was statistically significantly greater for early combined therapy compared to conventional treatment, but there was no difference between groups after 10 weeks. A non-randomized study by Ghazi et al.19 found no difference in HBI score between groups at 3, 6, and 12 months. When HBI change from baseline was compared between groups, there was a statistically significant difference for reduction in HBI score in favour of early biologic therapy at 3 months (suggesting greater improvement in symptoms), but not at 6 or 12 months. HBI scores were statistically significantly higher in the early biologic group at baseline.

Adverse outcomes of Crohn’s disease

Khanna et al.17 measured the time to adverse outcomes (a composite for surgery, hospital admission, or disease complication) and found a statistically significantly reduced rate of adverse outcomes in the early combined intervention group versus conventional therapy group. This was a secondary endpoint that was not pre-specified in the protocol and the authors note should be interpreted with caution.

Corticosteroid use

There were data from two RCTs16,17 and two non-randomized19,22 studies pertaining to corticosteroid use. Khanna et al.17 found the time to corticosteroid treatment was not different between early combined intervention and conventional therapy over 24 months. D’Haens et al.16 reported that persons in the early combined treatment group had lower exposure to corticosteroids compared to conventional treatment (statistical significance not reported). Long-term follow-up from D’Haens et al.18 found that the proportion of persons treated with corticosteroids at any point during follow-up was significantly lower for early combined therapy versus conventional therapy. The non-randomized study by Ghazi et al.19 found that the proportion of people receiving corticosteroids was statistically significantly lower in the early biologic group compared to step-up therapy at 3 months but there was no difference at 6 or 12 months. The non-randomized study by Rubin et al.22 found that the step-up therapy was associated with a significantly higher risk of receiving corticosteroids compared to early anti-TNF treatment at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months.

Quality of life

Khanna et al.17 reported no difference in EQ-5D or SF-36 scores between the early combined intervention and conventional treatment at any time point. In the D’Haens et al. RCT,16 there was a statistically significant increase in IBDQ (suggesting improved disease-related quality of life) for early combined therapy compared to conventional therapy at 10 weeks but there was no difference beyond this time point. The non-randomized study by Ghazi et al.19 reported no difference in SIBDQ between early biologic or step-up therapy at 3, 6, or 12 months. When change from baseline was measured, there was a statistically significantly greater improvement in SIBDQ at 6 months in the early combined group, but not at 3 or 12 months. The baseline SIBDQ was lower in the early biologic group at baseline.

Mortality

Khanna et al.17 found no difference in mortality between the early combined intervention and conventional treatment over 24 months.

Surgery for Crohn’s disease

Khanna et al.17 found a statistically signification reduction in the rate of surgery in the early combined intervention group versus conventional therapy. Long-term follow-up over 8 years from the D’Haens et al.18 RCT reported no difference in the proportion undergoing Crohn’s disease-related surgery between groups. Ghazi et al.19 found no difference in the number of surgeries between the early biologic and step-up groups, while Rubin et al.22 found an step-up therapy was associated with a statistically significantly increased risk of Crohn’s disease-related surgery in people receiving step-up therapy compared to early anti-TNF treatment.

Hospitalization for Crohn’s disease

Khanna et al.17 and the long-term follow-up18 from D’Haens et al. found no difference in the rate of hospitalization between early biologic therapy and conventional treatment. Ghazi et al.19 reported a significantly increased number of hospitalizations at 1 year in the early biologic group compared to the step-up group.

Serious complications

Khanna et al.17 found a statistically significant reduction in the rate of complications (new abscess, fistula, stricture, serious worsening of disease activity, extra-intestinal manifestations) for the early combined intervention group versus conventional therapy. Long-term follow-up from D’Haens et al.18 found no difference in the proportion of people developing fistulas between groups.

Endoscopic findings

The proportion of people with no ulcers at 104 weeks was significantly lower in the early combined group compared to conventional treatment in the D’Haens et al RCT.16 The endoscopy score was also significantly lower in the early combined group. The long-term follow-up study from this trial found no difference between groups in the proportion of people without ulcers over 8 years.18

Endoscopic remission and mucosal healing

The non-randomized study by Fan et al.21 found that a higher proportion of people receiving top-down therapy achieved complete endoscopic remission (CDEIS < 3) compared to step-up therapy at week 30 and week 54, though the differences were not statistically significant. There was a statistically significantly higher proportion of people with endoscopic remission (CDEIS < 6) at week 30 but not at week 54.

Fan et al.21 found that a significantly higher proportion of participants achieved mucosal healing in the top-down therapy group compared to the step-up group at week 30, but the difference was not significant at week 54 and week 102.

Safety

The RCT by Khanna et al.17 found a similar proportion of participants with adverse drug events. In the RCT by D’Haens et al.16, the proportion of participants with adverse events was higher in the early combined therapy group versus conventional management group (31% versus 25%), but there were no notable differences in individual events. Long-term follow-up of the D’Haens trial18 found that serious infections were more common in the early combined therapy persons compared to conventional treatment (22% versus 10%). The observational study by D’Haens et al. (2017)20 was designed to assess the safety of infliximab over 5 years. This study found that exposure to infliximab in the context of early biologic treatment was associated with a significantly increased risk of serious infections and hematological conditions with no increase in malignancy or lymphoproliferative disorders, compared to those receiving conventional treatment (and never receiving infliximab). Fan et al.21 examined the proportion of people with adverse events and found that 90% experienced an adverse event in the top-down group versus 85% in the step-up group (infusion reactions occurred in 13% of top-down versus 0% for step-up).

Clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy in children

Remission

Four non-randomized studies reported remission.27–30 Kang et al.27 found that the proportion of those in clinical remission was no different between early combined and step-up therapy at week 14 versus 54. In the study by Lee et al. (2015),30 the proportion of people who achieved clinical remission was a statistically significantly higher at 1 year in the top-down group compared to the step-up group. Walters et al.29 found that the early biologic therapy was associated with a significantly higher corticosteroid-free clinical remission rate compared to the group receiving no immunosuppressant or early immunosuppressants. Kim et al.28 found that the remission rate in the top-down group was statistically significantly greater compared to step-up treatment at both 8 weeks and 1 year.

Relapse

Relapse was examined in three non-randomized studies. Lee et al. (2015)30 found that people receiving top-down therapy were significantly more likely to remain relapse-free over3 years to those receiving step-up therapy. Lee et al. (2012)25 found that the proportion of people who relapsed was lower in the top-down group compared to the step-up group at 1, 2, and 3 years, but the difference was only statistically significant at year 2. Lee et al. (2010)26 found that the proportion of people who relapsed was significantly lower in those receiving early combined therapy compared to those receiving AZA only or mesalamine, at 1 and 2 years.

Disease activity score

Kang et al.27 found there was no difference in PCDAI score between early combined and step-up treatment at 14 and 54 weeks. In the study by Kim et al.28 top-down treatment produced a statistically significantly greater improvement in PCDAI score compared to step-up treatment at both 8 weeks and 1 year.

Fistula closure

Kim et al.28 reported that in people with fistulas at baseline, the proportion with fistula closure at 8 weeks and 1 year was significantly greater in the top-down group compared to step-up.

Mucosal healing

Kang et al.27 found that the proportion of persons with mucosal healing was no different between groups at week 14 but was significantly higher at week 54 in the early combined group compared to the step-up group.

Endoscopic findings

Kang et al.27 reported that the SES-CD score was significantly lower in the early combined group compared to step-up group at both week 14 and 54 (suggesting lower mucosal involvement).

Safety

Kang et al.27 and Lee et al.(2015)30 reported no overall differences in adverse events between groups. Lee et al. (2015) found that more people in the top-down group experienced leukopenia as well as nausea and vomiting, while more participants in the top-down group experienced pancreatitis. Lee et al. (2010)26 found that fewer participants experienced an adverse event in the early biologic + AZA group (8%) compared to either AZA alone (39%) or mesalamine alone (30%); however, the number of people in each group was small. In the Kim et al.28 study, 36% of people experienced an adverse effect in the step-up group compared to 45% in the top-down group (there were no notable differences between groups).

Cost-effectiveness of early biologic therapy in adults

Top-down therapy improved quality-adjusted life expectancy and was cost-saving compared to step-up therapy.23 Time horizon and cost of infliximab had an important influence in sensitivity analysis. With a time horizon of 1 year the incremental cost-utility ratio was €92,440/QALY while at year 4 it was €1,462/QALY and dominant at year five.

Cost-effectiveness of early biologic therapy in children

No relevant evidence was identified and therefore no summary can be provided.

Limitations

Adults

One of the central challenges in interpreting the evidence is heterogeneity in the study populations and interventions tested. This makes it difficult to compare results across studies and draw conclusions about the body of evidence as a whole. For example, the two eligible RCTs comprising the highest quality evidence examined different populations and treatment approaches. Khanna et al.17 tested a treatment algorithm where early combined biologic therapy could be initiated after a 4- or 12-week course of corticosteroids (20% ended up on combined therapy). However, all people in the intervention group in D’Haens et al.16 received early combined therapy with a biologic from baseline. With regard to study population, some studies excluded persons with fistulizing disease while others did not, which also contributed to heterogeneity. Another challenge is that most studies focused only on a clinical definition of remission without endoscopic assessment (e.g. mucosal healing or endoscopic remission). Relying on a clinical definition of remission alone may be insufficient as this does not necessarily indicate that the natural course of the disease has been changed.32 Further, there were limited data on surgery and hospitalization (the avoidance of which are noted to be theoretical benefits to a top-down approach). It has been suggested that endoscopic findings are particularly important to evaluate as mucosal healing is important in changing disease course,32 reducing risk of complications and surgery (rather than relying on clinical symptoms alone).1–3

The cost-effectiveness study was based on people who were newly diagnosed and treatment naïve, thus it is unclear whether the results would apply to other patient populations. Analysis was conducted from the perspective of the Italian healthcare system using Italian healthcare and drug costs, thus it is unclear whether the findings are generalizable in a Canadian context. Finally, indirect costs were not considered in the model the authors used.

Children

Five of the six studies conducted in children were conducted at the same single hospital in South Korea. The generalizability of findings from these studies to the Canadian context is uncertain. These were small, studies (sample size ranging from n=28 to n=76) at high risk of bias due to concerns surrounding selection bias. There were also concerns surrounding heterogeneity in the studies conducted in children. The study population (e.g. severity and type of disease) and comparator intervention differed across studies making it challenging to compare results. As in adults, there was limited evidence on endoscopic findings and no evidence on surgery or hospitalization.

There were no cost-effectiveness data for children.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

This report identified two RCTs (and one long-term follow-up study of one RCT) and four non-randomized studies examining the clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease in adults. There was one economic evaluation on the cost-effectiveness of early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease in adults. The report also identified six non-randomized studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease in children.

Adults

As discussed, the identified studies were heterogeneous in terms of both study populations and interventions, making it challenging to draw conclusions across studies. The results from the two eligible RCTs were conflicting. One study17 by Khanna et al. found that an early biologic treatment algorithm made no difference in clinical remission rates or symptom severity scores at one year compared to conventional treatment, while the other16 reported that early biologic therapy increased the rate of clinical remission compared to conventional treatment at one year. The RCT by D’Haens et al. reporting benefit on remission rates16 also reported improved symptom severity scores and disease-related quality of life at 10 weeks, but there was no difference thereafter. There were differences in the conduct of these two trials. The RCT demonstrating benefit in remission rates for early combined therapy was conducted in treatment-naïve persons with a two-week duration between diagnosis and treatment. All people received early combined therapy from baseline in this trial. In comparison, for the trial reporting no benefit on remission,17 people had longer standing disease (mean disease duration approximately 10 years), less severe disease, and over half were in remission at baseline. Further, as part of the early biologic treatment algorithm, there was a corticosteroid induction phase of 4 or 12 weeks, such that treatment biologics was delayed from baseline (further, not all participants in the intervention group actually received biologics).17 While the evidence on clinical remission rates and symptom severity scores is limited and conflicting, it is possible that the clinical benefit of early combined therapy may depend on the patient population and timing of initiation of therapy. This has also been suggested by a recent narrative review on the topic.8

The effect of early biologic therapy on Crohn’s-related surgery and complications was also conflicting and uncertain, though one RCT pointed to a possible benefit in favour of early biologic therapy. The rate of Crohn’s-related surgery and the rate of complications were both lower in the early combined intervention group in the RCT by Khanna et al.17 However, long-term follow-up of people from another RCT over 8 years18 found no difference in the proportion undergoing surgery, being hospitalized, or developing fistulas. There was conflicting evidence surrounding the effect of early biologics on rates of surgery in non-randomized studies.

There were limited data on endoscopic remission from two studies. One non-randomized study21 found that rates of endoscopic remission were higher with early biologic treatment, but the difference was not significant. This study also reported that the proportion of people with mucosal healing was higher with early biologic therapy at week 30, but not different at 2- or 3-years follow-up. However, this was a small (n=77), open-label study with concerns surrounding confounding. The proportion of participants with no ulcer was higher with early biologic treatment in the D’Haens et al. RCT.16 These results point to possible positive effects on endoscopic findings, but given the limitations in evidence the benefits are uncertain.

A large, long-term observational study found that infliximab in the context of early biologic therapy increased the risk of serious infections and hematological conditions, with no increase in malignancy or lymphoproliferative disorders, compared to people on conventional therapy (that did not include infliximab).20 The authors noted that these findings appear consistent with the known side effect profile of anti-TNF agents.

Overall, clinical evidence in adults was limited in that there were few studies, with concerns related to design, methods, and generalizability. There were concerns surrounding risk of bias in both RCTs related to allocation concealment and an open label design (and influence on outcome measurement). In the non-randomized studies, there was possible selection bias and confounding in many of the studies, reducing confidence in results. Another limitation is that most studies focused on clinical endpoints, which may be inappropriate, since it is suggested that the effectiveness of a treatment strategy should be based on its ability to modify natural course of the disease. The limitations of these studies should also be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

The results of one cost-effectiveness study in newly-diagnosed adult persons who were treatment naïve suggested that early biologic therapy was cost-saving and more effective compared to step-up therapy. This study suggests that early biologic therapy could be cost-effective. The study was conducted from the Italian healthcare system perspective; thus, the extent to which this analysis applies in Canada is unclear, particularly as drug cost had an important impact on cost-effectiveness estimates in sensitivity analyses.

Children

Evidence in children was limited, as noted above. Only non-randomized studies were identified, all of which had methodological concerns. Five of the studies had small sample sizes and were conducted at one hospital in South Korea, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Three studies28–30 reported that early biologic therapy increased rate of remission, while one study27 found no difference between early biologic therapy and conventional treatment. Three studies25,26,30 also found that the rate of relapse was lower with early biologic therapy compared to conventional treatment. There was conflicting evidence on disease activity scores. In one study, the endoscopic severity of disease was lower with early biologic therapy compared to step-up therapy at 14 weeks and 54 weeks.27 In this study, the proportion of participants with mucosal healing was higher with early biologic therapy at 54 weeks but not at 14 weeks. There was no evidence surrounding surgery or hospitalizations. Adverse event reporting was limited in all studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, whether early biologic therapy is more effective than conventional therapy for Crohn’s disease in adults is unclear due to a limited number of studies, insufficient data on endoscopic remission, and heterogeneity of existing studies. Available evidence does not suggest a clear and consistent benefit for early biologic therapy across outcomes. Existing evidence points to possible benefits; however, future randomized controlled trials are likely required to clarify the clinical effectiveness of early biologic therapy (and also to clarify in which patient groups it is most appropriate).

Given the size and quality of the evidence base in children, no firm conclusions can be drawn about the comparative effectiveness of early biologic therapy in this group. Further research, preferably in the form of an RCT, is required to assess the effectiveness and safety of early biologic therapy compared to conventional therapy for Crohn’s disease in children.

The results of this report are consistent with a recent narrative review.8 The authors of the review also concluded that based on current evidence, early biologic treatment does not appear to have a clear benefit over conventional (step-up) therapy, though some studies suggest possible benefits. This review also noted that available evidence was limited (both in number and design of studies) and that the evidence base in children was particularly inconclusive.

References

- 1.

Baumgart

D, Sandborn

W. Crohn’s disease.

Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1590–1605. [

PubMed: 22914295]

- 2.

Kalla

R, Ventham

N, Satsangi

J, Arnott

I. Crohn’s disease.

BMJ. 2014;349. [

PubMed: 25409896]

- 3.

Feuerstein

J, Cheifetz

A. Crohn Disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management.

Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(7):1088–1103. [

PubMed: 28601423]

- 4.

- 5.

Molodecky

N, Soon

I, Rabi

D, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review.

Gastroenterol. 2012;142(1):46–54.e42; quiz e30. [

PubMed: 22001864]

- 6.

Benchimol

E, Fortinsky

K, Gozdyra

P, Van den Heuvel

M, Van Limbergen

J, Griffiths

A. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends.

Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):423–439. [

PubMed: 20564651]

- 7.

Rogler

G. Top-down or step-up treatment in Crohn’s disease?

Dig Dis. 2013;31(1):83–90. [

PubMed: 23797128]

- 8.

- 9.

Cozijnsen

MA, van Pieterson

M, Samsom

JN, Escher

JC, de Ridder

L. Top-down Infliximab Study in Kids with Crohn’s disease (TISKids): an international multicentre randomised controlled trial.

BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000123. [

PMC free article: PMC5223648] [

PubMed: 28090335]

- 10.

Baert

F, Moortgat

L, Van Assche

G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn’s disease.

Gastroenterol. 2010;138(2):463–468; quiz e410-461. [

PubMed: 19818785]

- 11.

Colombel

JF, Sandborn

WJ, Reinisch

W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s Disease.

New England J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. [

PubMed: 20393175]

- 12.

Higgins

J, Sterne

J, Savović

J, et al. RoB 2.0: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(1).

- 13.

- 14.

- 15.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 16.

D’Haens

G, Baert

F, van Assche

G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial.

Lancet. 2008;371(9613):660–667. [

PubMed: 18295023]

- 17.

Khanna

R, Bressler

B, Levesque

BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial.

Lancet. 2015;386(10006):1825–1834. [

PubMed: 26342731]

- 18.

Hoekman

DR, Stibbe

JA, Baert

FJ, et al. Long-term Outcome of Early Combined Immunosuppression Versus Conventional Management in Newly Diagnosed Crohn’s Disease.

J Crohn Colitis. 2018;12(5):517–524. [

PubMed: 29401297]

- 19.

Ghazi

LJ, Patil

SA, Rustgi

A, Flasar

MH, Razeghi

S, Cross

RK. Step up versus early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease in clinical practice.

Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1397–1403. [

PubMed: 23598813]

- 20.

D’Haens

G, Reinisch

W, Colombel

JF, et al. Five-year Safety Data From ENCORE, a European Observational Safety Registry for Adults With Crohn’s Disease Treated With Infliximab [Remicade] or Conventional Therapy.

Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2017;11(6):680–689. [

PubMed: 28025307]

- 21.

Fan

R, Zhong

J, Wang

ZT, Li

SY, Zhou

J, Tang

YH. Evaluation of “top-down” treatment of early Crohn’s disease by double balloon enteroscopy.

World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(39):14479–14487. [

PMC free article: PMC4202377] [

PubMed: 25339835]

- 22.

Rubin

D, Uluscu

O, Sederman

R. Response to biologic therapy in Crohn’s disease is improved with early treatment: an analysis of health claims data.

Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(12):2225–2231. [

PubMed: 22359399]

- 23.

Marchetti

M, Liberato

N, Di Sabatino

A, Corazza

G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of top-down versus step-up strategies in patients with newly diagnosed active luminal Crohn’s disease.

Eur J Health Economics. 2013;14(6):853–861. [

PubMed: 22975794]

- 24.

Kim

M, Lee

W, Choi

K, Choe

Y. Effect of infliximab top-down therapy on weight gain in pediatric Crohns disease.

Indian Ped. 2012;49(12):979–982. [

PubMed: 22728632]

- 25.

Lee

Y, Baek

S, Kim

M, Lee

Y, Lee

Y, Choe

Y. Efficacy of early infliximab treatment for pediatric Crohn’s Disease: a three-year follow-up.

Ped Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2012;15(4):243–249. [

PMC free article: PMC3746055] [

PubMed: 24010094]

- 26.

- 27.

Kang

B, Choi

S, Kim

H, Kim

K, Lee

Y, Choe

Y. Mucosal healing in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe luminal Crohn’s Disease under combined immunosuppression: escalation versus early treatment.

J Crohn Colitis. 2016;10(11):1279–1286. [

PubMed: 27095752]

- 28.

Kim

M, Lee

J, Lee

J, Kim

J, Choe

Y. Infliximab therapy in children with Crohn’s disease: a one-year evaluation of efficacy comparing ‘top-down’ and ‘step-up’ strategies.

Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(3):451–455. [

PubMed: 20626362]

- 29.

Walters

TD, Kim

MO, Denson

LA, et al. Increased effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn’s disease.

Gastroenterol. 2014;146(2):383–391. [

PubMed: 24162032]

- 30.

Lee

Y, Kang

B, Lee

Y, Kim

M, Choe

Y. Infliximab “top-down” strategy is superior to “step-up” in maintaining long-term remission in the treatment of pediatric Crohn Disease.

J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(6):737–743. [

PubMed: 25564801]

- 31.

- 32.

Baert

F, Moortgat

L, Van Assche

G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn’s disease.

Gastroenterol. 2010;138(2):463–468; quiz e410-461. [

PubMed: 19818785]

- 33.

Best

WR, Becktel

JM, Singleton

JW, Kern

F, Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study.

Gastroenterol. 1976;70(3):439–444. [

PubMed: 1248701]

- 34.

- 35.

Guyatt

G, Mitchell

A, Irvine

EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease.

Gastroenterol. 1989;96(3):804–810. [

PubMed: 2644154]

- 36.

Hyams

J, Markowitz

J, Otley

A, et al. Evaluation of the pediatric crohn disease activity index: a prospective multicenter experience.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(4):416–421. [

PubMed: 16205508]

- 37.

Irvine

EJ, Zhou

Q, Thompson

A. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial.

Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(8):1571–1578. [

PubMed: 8759664]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Description of Scales

View in own window

| Scale | Scoring and definitions |

|---|

| Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI)33 | Measure of disease activity – includes patient reported information on bowel movements, abdominal pain, wellbeing, extra-intestinal symptoms, medication use, weight Score ranges from 0 to 600, remission < 150, 200 to 300 = moderate to severe disease, >300 = severe disease; clinical response is a fall of >70 points |

| Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS)34 | For determining severity of Crohn’s disease endoscopically Remission is categorized as <3, a score of 3 to 8 is mild endoscopic activity, a score of 9 to 12 is moderate endoscopic activity, and >12 severe activity |

| Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI)34 | Patient and physician completed questionnaire on general well-being, abdominal pain, bowel movements, and other symptoms Remission categorized as <5, mild disease 5 to 7, moderate disease 8 to 16, severe disease >16 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ)35 | Disease-related quality of life instrument with 32 questions Higher scores suggest improved quality of life (range from 32 to 224) |

| Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI)36 | Measure of disease activity incorporating symptoms, laboratory measurements, and physical findings Scores range from 0 to 100, higher scores represent more severe disease Remission categorized as PCDAI < 10, mild disease 11 to 30, moderate to severe disease >30, and a decrease of 12.5 points or more suggests an improvement in disease |

| Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD)34 | Assess mucosal ulcers, presence of stenosis Score of 0 to 2 suggest remission, 3 to 6 mild endoscopic activity, 7 to 15 moderate endoscopic activity, >15 severe activity (a decrease of 50% has been suggested as clinically significant) |

| Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)37 | Shortened 10-item version of IBDQ scored from 10 to 70 points where higher scores suggest improved quality of life |

Table 3Characteristics of Included Randomized Studies in Adults

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Khanna 2015; Belgium and Canada17 | Open-label cluster randomized controlled trial Gastroenterology practices were randomized 1:1 to use either an early combined immunotherapy algorithm or conventional treatment; a minimization procedure was used to balance by country and practice size; there were 21 early combined practices and 18 conventional treatment practices, around 87% were in Canada | n=1982, ~42% male ≥18 years old (mean age 44) Crohn’s disease regardless of disease activity or existing treatments (56% classified as being in steroid-free remission at baseline); 7% had active fistula Mean disease duration 149 months for early combined versus 158 for conventional | Early combined immunosuppression algorithm: if continuing disease activity (HBI >4) after steroid induction of 4 or 12 weeks, patients received combined anti-TNF and antimetabolite (choice of investigator); treatment could be modified every 12 weeks after reassessment Conventional management: usual practice | Primary outcome: mean proportion of patients in corticosteroid-free remission (HBI < 5) at month 12 Secondary outcomes: mean proportion of patients in remission at 6, 8 and 24 months; difference in mean HBI at 6, 8 and 24 months; time to first adverse outcome (surgery, complication or hospital admission); time to corticosteroids; adverse events, quality of life, mortality |

| D’Haens 2008; Belgium, Netherlands, Germany16 | Open-label randomized controlled trial Patients were randomized into two groups in blocks of four; a minimization procedure was used | n = 133, 62% female Age 18 to 75 (mean~30) diagnosed with Crohn’s in past 4 years (mean 2 weeks from diagnosis to treatment) and had clinically active disease; mean CDAI score was 330 in the combined immunosuppression group and 306 in the conventional therapy group Had not received biologics, corticosteroids or antimetabolites; patients with stenosis or strictures were excluded | Combined immunosuppression: infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks in combination with AZA 2 to 2.5mg/kg per day (patients intolerant to AZA were given methotrexate 25 mg per week for 12 weeks then 15 mg per week); if responded, continued for rest of trial; if symptoms worsened additional infusions of infliximab were given Conventional: induction treatment with methylprednisolone (32 mg daily for 3 weeks then tapered over 4 weeks) or budesonide (9 mg per day for 8 weeks then tapering); if symptoms worsened the corticosteroid course was repeated at higher dose; if symptoms continued to worsen, AZA was added; if relapse patients received another course of corticosteroids; if symptomatic after 16 weeks with AZA, received infliximab | Patients were assessed at week 2, 6, 10, 14, 26 and then every 12 weeks until 104 weeks Primary outcome: remission defined as CDAI score of less than 150, absence of corticosteroids and no intestinal resection at 26 and 52 weeks Secondary outcomes: time to relapse (CDAI increase >50), treatment with corticosteroids, CDAI and IBDQ scores, mean endoscopic severity scores, proportion in remission at week 14 (CDAI and no corticosteroid); proportion without ulcers after 24 months, adverse events |

| Hoekman 2018 (follow-up from D’Haens 2008)18 | Retrospective review of patients included in D’Haens 2008 open-label randomized controlled trial; data were collected between 2003 and 2014 to allow for an 8-year follow-up from patients in the original trial | Data available for 119/133 patients | See D’Haens 2008 | Follow up over 8 years (split into 16 semesters) Primary outcome: proportion of patients in remission (not defined) Secondary outcomes: hospitalization, surgery, new fistula, rescue treatment, flares, disease activity |

Abbreviations: AZA = azathioprine; CDAI = Crohn’s disease activity index; HBI = Harvey-Bradshaw Index; IBDQ = inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

Table 4Characteristics of Included Non-Randomized Studies in Adults

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| D’Haens 2017, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, UK20 | Observational prospective registry study Patients from ENCORE registry, a prospective registry that enrolled from 2003 to 2008 and followed patients for 5 years; patients were eligible when Crohn’s disease treatment (e.g. corticosteroid, immunomodulator, anti-TNF) intensification was indicated; authors identified three groups of patients to compare | n = 2662, ~60% female, 95% Caucasian Age 16 to 86 (median age ~35) with active luminal or fistulizing Crohn’s and no previous exposure to anti-TNF treatment Mean time since diagnosis ~8.5 years; 28% had a fistula in conventional group, 43% in early infliximab group, 27% in switch to infliximab group | Infliximab within 30 days of enrolment visit Conventional therapy: treatment without anti-TNF agents Started with conventional therapy and switched to infliximab during follow up

| Adverse events as reported by the treating physician, assessed every 6 months according to 7 pre-specified categories Safety data were reported as: (1) frequency of all observed adverse events, (2) incidence per 1000 person-years, (3) multivariable analysis by treatment, (4) multivariable analysis accounting for latest infliximab dose relative to onset of adverse events Some analyses were done based on exposure versus non-exposure to infliximab (patients in the step-up group who received infliximab were combined with the early infliximab group); only analyses comparing conventional to early infliximab are reported |

| Fan 2014, China21 | Controlled before-after (prospective study where one group received “top-down” therapy [group 1] and other group [group 2] received corticosteroid then azathioprine in a non-randomized open-label manner) | n=77, 47% male ≥18 years old (median age at onset was 25 years), newly diagnosed with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease and naïve to treatment (median disease duration was 10 weeks) Baseline CDAI score between 220 and 450 (median CDAI 279) with ileal and colonic mucosal ulcerations; excluded if fibrostenotic, fistulizing or penetrating disease | (1) Induction with infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2, 6, 14, 22 and 30 weeks plus azathioprine 1 to 2.5 mg/kg daily from week 6 onwards (titrated to maximum tolerated dose) (2) prednisone 1 mg/kg daily for 7 to 14 days and tapered over 6 to 12 weeks plus AZA 1 to 2.5 mg/kg daily from week 6 onwards (titrated to maximum tolerated dose) | Primary endpoint: deep remission at week 30, 54 and 102 (CDAI score < 150 plus complete absence of mucosal ulcerations observed at baseline) Secondary endpoints: time to clinical remission; clinical remission at week 2, 6, 14, 22, 30, 54, 102; change from baseline for CDEIS score at week 30 and 54; complete endoscopic remission (CDEIS <3); endoscopic remission (CDEIS<6) Adverse events |

| Ghazi 2013, USA19 | Retrospective chart review from the University of Baltimore Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program Charts were reviewed from 2004 to 2010 in patients who were anti-TNF naïve and patients were grouped into two groups: early biologic or step-up | n=93, 59% female Mean age at diagnosis was 28 and mean duration of disease was 11 years 48% of patients had penetrating disease Mean baseline HBI was 3.7 in the step up group and 6.3 in the early biologic group | Early biologic: initial treatment with infliximab 5 mg/kg at week 0, 2, 6 and maintenance every 8 weeks or adalimumab 160 mg at week 0, 80 mg at week 2, then 40 mg every 2 weeks or certolizumab 400 mg at week 0, 2, and 4 then every 4 weeks (the dose interval could be increased or decreased) with or without an immunosuppressant Step-up: immunosuppressant alone or starting an immunosuppressant before an anti-TNF | Response and remission rates (HBI<5), HBI, SIBDQ, steroid free-remission, number of hospitalizations and surgeries at 0, 3, 6 and 12 months after initiation, corticosteroid use |

| Rubin 2012, USA22 | Retrospective cohort study Patients were identified using from an administrative claim database (PharMetrics) between 2000 and 2009 using ICD-9 codes and drug claims; patients had to be continuously enrolled in the same health plan for 6 months prior to their first claim and remain enrolled 12 months after anti-TNF claims; 3 groups were created based on treatment | n=3750, 60% female Median age 40 11% had an anal fistula | Step-up: 5-ASA and/or corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants prior to anti-TNF “IS-to-TNF”: immunosuppressants only prior to anti-TNF Early-TNF: initiation of anti-TNF within 30 days of first prescription for Crohn’s disease | Concomitant corticosteroid use, Crohn’s disease surgery At 6, 12, 18 and 24 months |

Abbreviations: ASA = aminosalicylicacid; AZA = azathioprine; CDAI = Crohn’s disease activity index; CDEIS = Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity; HBI = Harvey-Bradshaw Index; IS = immunosuppressant; SIBDQ = Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; TNF = tumor necrosis factor

Table 5Characteristics of Included Non-Randomized Studies in Children

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Kang 2016, South Korea27 | Prospective observational study comparing two groups of patients who received infliximab: either as part of step-up or top-down Patients prospectively enrolled and could choose to receive step-up or top-down with their guardian after explanation of options Study was specifically interested in those who received infliximab (either early or as part of step-up) and therefore only included in step-up group if eventually received infliximab after failure of conventional therapy | n=76, median age at diagnosis 14 years for step-up and 15 year for top-down, 64% male, median PCDAI = 35, median duration to infliximab treatment 8 months in step-up and 0.7 months in top-down Pediatric patients (< 18 years of age) with moderate to severe luminal disease were included (excluded if mild disease, penetrating disease, strictures, refractory perianal strictures or history of bowel surgery) | Top-down: within 1 month from diagnosis, infliximab 5mg/kg at 0, 2, 6, 14 weeks then every 8 weeks plus AZA 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day (adjusted as required) plus mesalazine 50 mg/kg/day Step-up: oral corticosteroid (not specified) 1 mg/kg/day tapered over 8 weeks plus AZA 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day (adjusted as required) plus mesalazine 50 mg/kg/day; if disease relapsed then infliximab initiated (as in top-down group) | Primary outcome: mucosal healing (SES-CD score=0) at 14 and 54 weeks from baseline infliximab Secondary outcomes: clinical remission (PCDAI<10), PCDAI, adverse events, SES-CD score Baseline was first infliximab dose |

| Lee 2015, South Korea30 | Retrospective review of a prospective study Conducted at one hospital based on patients from 2008 to 2012; 2 groups depending on treatment received (therapy decisions made by guardians after explanation of treatment options) | n = 51, median age at diagnosis 15 years old, sex not described Patients had moderate to severe Crohn’s (PCDAI 39 in top-down and 34 in step-up at baseline) Disease duration 1 month in top-down versus 10.8 months in step-up 71% had fistula in top-down and 55% in step-up Patients in step-up initially achieved remission on conventional but eventually required infliximab | Top-down: patients who started infliximab at the time of diagnosis (in combination with AZA, mesalazine and corticosteroids) Step-up: patients who started infliximab after relapse (and where remission had been achieved with conventional therapy) Infliximab given 5 mg/kg week 0, 2, 6 then every 8 weeks | Disease remission (PCDAI < 10 points) Relapse free rate (relapse defined as PCDAI > 10 points after clinical remission), adverse events Follow-up over 3 years |

| Walters 2014, USA and Canada29 | Prospective observational study (data from 28 pediatric gastroenterology centres in North America from 2008 to 2012); propensity score matching to create three groups: (1) early anti-TNF, (2) early immunomodulator, (3) no early immunotherapy | n=552 (propensity score matched sample n=204); median age 13.8 years for anti-TNF, 12.6 years for immunomodulator, 12.0 years for no therapy; 62% male; 45% with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease Patients <17 years of age newly diagnosed with non-penetrating, non-stricturing disease were included; patients receiving early anti-TNFα in combination with an early immunomodulator were excluded | Three groups:

- (1)

early anti-TNF - (2)

early immunomodulator - (3)

no early immunotherapy

Early = within 3 months of diagnosis; all patients could receive corticosteroids or mesalamine | Primary outcome: corticosteroid free clinical remission (PCDAI < 10) at 1 year after diagnosis |

| Lee 2012, South Korea25 | Retrospective chart review Charts were reviewed at one hospital in patients followed for at least 36 months between 1998 and 2009; patients were put into 2 groups depending on treatment received | n = 28, 14% female Mean age 13 years Mean PCDAI score at diagnosis 40.5 Patients either had moderate or severe CD (top-down group) or had therapy-resistant CD (step-up group) | Top-down: infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2, 6 weeks then every 8 weeks for 10 months in combination with AZA daily Step-up: oral prednisolone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day and mesalamine (50 to 80 mg/kg/day) or AZA (2 go 3 mg/kg/day), then infliximab | Relapse (PCDAI > 10 points after remission) Evaluated at 1, 2, and 3 years |