Summary

Clinical characteristics.

Costeff syndrome is characterized by optic atrophy and/or choreoathetoid movement disorder with onset before age ten years. Optic atrophy is associated with progressive decrease in visual acuity within the first years of life, sometimes associated with infantile-onset horizontal nystagmus. Most individuals have chorea, often severe enough to restrict ambulation. Some are confined to a wheelchair from an early age. Although most individuals develop spastic paraparesis, mild ataxia, and occasional mild cognitive deficit in their second decade, the course of the disease is relatively stable.

Diagnosis/testing.

The diagnosis of Costeff syndrome is established in a proband with suggestive findings by identification of biallelic OPA3 pathogenic variants on molecular genetic testing.

Management.

Treatment of manifestations: Supportive and often provided by a multidisciplinary team; treatment of visual impairment, spasticity, and movement disorder as in the general population.

Agents/circumstances to avoid: Use of tobacco, alcohol, and medications known to impair mitochondrial function.

Genetic counseling.

Costeff syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. If both parents are known to be heterozygous for an OPA3 pathogenic variant, each sib of an affected individual has at conception a 25% chance of being affected, a 50% chance of being an unaffected carrier, and a 25% chance of being unaffected and not a carrier. When both OPA3 pathogenic variants have been identified in an affected family member, carrier testing for at-risk family members, prenatal testing for pregnancies at increased risk, and preimplantation genetic testing are possible.

Diagnosis

Suggestive Findings

The diagnosis of Costeff syndrome is suspected in a child with the following clinical and laboratory findings and family history consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance.

Clinical Findings

Early in the disease course

- Relatively normal early development and growth

- Bilateral early-onset optic atrophy (pathologically pale optic discs, attenuated papillary vasculature, and visual evoked potentials that show bilateral prolonged latencies consistent with optic atrophy)

- Choreoathetoid movement disorder

Later in the disease course

- Progressive spasticity

- Cerebellar ataxia

- Cognitive deterioration (in a minority of individuals)

Laboratory Findings

Increased urinary excretion of 3-methylglutaconate (3-MGC) and 3-methylglutaric acid (3-MGA). In Costeff syndrome, urinary 3-MGC and 3-MGA (measured using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) are mildly increased. Note: (1) In Costeff syndrome, the excretion of 3-MGC and 3-MGA is variable, sometimes even overlapping that of normal controls; furthermore, 3-MGC and 3-MGA are not always easy to detect on urine organic acid analysis. (2) Because laboratories both within and between countries use different methods, they have very different reference ranges; thus, the sex- and age-specific reference range determined by each reference laboratory should be used.

Establishing the Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Costeff syndrome is established in a proband with suggestive findings and biallelic OPA3 pathogenic variants identified by molecular genetic testing (Table 1).

Molecular genetic testing approaches can include a combination of gene-targeted testing (single-gene testing or multigene panel) and comprehensive genomic testing (exome sequencing and genome sequencing) depending on the phenotype.

Gene-targeted testing requires that the clinician determine which gene(s) are likely involved, whereas genomic testing does not. Because the phenotype of Costeff syndrome is broad, individuals with the distinctive findings described in Suggestive Findings are likely to be diagnosed using gene-targeted testing (see Option 1), whereas those in whom the diagnosis of Costeff syndrome has not been considered are more likely to be diagnosed using genomic testing (see Option 2).

Option 1

Single-gene testing. Sequence analysis of OPA3 is performed first to detect small intragenic deletions/insertions and missense, nonsense, and splice site variants. Note: Depending on the sequencing method used, single-exon, multiexon, or whole-gene deletions/duplications may not be detected. If no variant is detected by the sequencing method used, the next step could be to perform gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis to detect (multi)exon and whole-gene deletions or duplications; to date, however, deletions/duplications have not been identified as a cause of Costeff syndrome.

Note: Targeted analysis for the c.143-1G>C pathogenic variant, which has been identified in all affected individuals of Iraqi Jewish descent, can be performed first in this population.

A multigene panel that includes OPA3 and other genes of interest (see Differential Diagnosis) is most likely to identify the genetic cause of the condition while limiting identification of variants of uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the underlying phenotype. Note: (1) The genes included in the panel and the diagnostic sensitivity of the testing used for each gene vary by laboratory and are likely to change over time. (2) Some multigene panels may include genes not associated with the condition discussed in this GeneReview. (3) In some laboratories, panel options may include a custom laboratory-designed panel and/or custom phenotype-focused exome analysis that includes genes specified by the clinician. (4) Methods used in a panel may include sequence analysis, deletion/duplication analysis, and/or other non-sequencing-based tests.

For an introduction to multigene panels click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genetic tests can be found here.

Option 2

Comprehensive genomic testing does not require the clinician to determine which gene(s) are likely involved. Exome sequencing is most commonly used; genome sequencing is also possible.

If exome sequencing is not diagnostic, exome array (when clinically available) may be considered to detect (multi)exon deletions or duplications that cannot be detected by sequence analysis; to date, however, deletions/duplications have not been identified as a cause of Costeff syndrome.

For an introduction to comprehensive genomic testing click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genomic testing can be found here.

Table 1.

Molecular Genetic Testing Used in Costeff Syndrome

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical Description

Most individuals with Costeff syndrome present within the first ten years of life with decreased visual acuity and/or choreoathetoid movement disorder. Although most develop spastic paraparesis, mild ataxia, and occasional mild cognitive deficit in their second decade, the course of the disease is relatively stable.

The following description of the phenotypic features of Costeff syndrome is based on two reports:

- Elpeleg et al [1994] reported on 36 affected individuals, 11 of whom were previously unreported and 25 of whom had been previously reported.

- Yahalom et al [2014] reported on 28 individuals (age range: 6 months – 68 years) six of whom were previously unreported and 22 of whom had been previously reported by Elpeleg et al [1994].

Optic Atrophy

Optic atrophy manifests as decreased visual acuity within the first years of life, sometimes associated with infantile-onset horizontal nystagmus.

In 36 individuals with Costeff syndrome, visual acuity decreased with age:

- In two children age two years, visual acuity appeared to be normal.

- In 14 individuals age three to 21 years (14.2±5.5), visual acuity was 6/21 or less.

- In 20 individuals age five to 37 years (18±9.5), visual acuity was 3/60 or less.

Some children have strabismus and gaze apraxia.

Motor Disability

Motor disability is primarily caused by extrapyramidal dysfunction and spasticity.

Extrapyramidal dysfunction. Most individuals have chorea, often severe enough to restrict ambulation. Some are confined to a wheelchair from an early age. In 36 individuals with Costeff syndrome, extrapyramidal involvement caused the following in 32 individuals:

- Major disability in 17 individuals age two to 37 years (mean 16.1±17.8)

- Minor disability in maintaining stable posture and fine motor activities in 12 individuals age two to 26 years (11.7±8.1)

- Mild manifestations with no resulting disability in three individuals age 15 to 36 years

No extrapyramidal involvement was observed in four individuals ages 13 to 32 years.

Spasticity. Unstable spastic gait, increased tendon reflexes, and Babinski sign may be seen. In 36 individuals with Costeff syndrome, spasticity was age-related:

- Nine individuals age two to 12 years (5.9±3.5) did not have spasticity.

- Four individuals age 11 to 26 years had mild spasticity but no related disability.

- Eleven individuals age 13 to 37 years (21.4±9.3) had mild spasticity-related disability.

- Twelve individuals age nine to 26 years (17.0±4.8) had severe spasticity-related disability.

Cerebellar dysfunction is usually mild. Ataxia and dysarthria caused mostly mild disability in 18 of the 36 individuals reported by Elpeleg et al [1994].

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment was previously noted in some individuals. Of 36 individuals:

- Nineteen individuals age two to 36 years (16±18.7) had an IQ of 71 or higher.

- Thirteen individuals age two to 37 years (14.7±9.2) had an IQ between 55 and 71.

- Four individuals age nine to 26 years had an IQ between 40 and 54.

More recently, however, a study of the neuropsychological profile of 16 adults with Costeff syndrome reported intact global cognition and learning abilities and strong auditory memory performance [Sofer et al 2015].

Other

Several affected individuals were reported to have married, four of whom (all female) had healthy offspring [Yahalom et al 2014].

Affected adults in the seventh decade of life have been reported [Yahalom et al 2014]; life expectancy beyond the seventh decade is unknown.

Seizures are not typical in Costeff syndrome. Partial seizures were reported in one individual. In addition, two individuals with Costeff syndrome were reported with electrical status epilepticus during slow-wave sleep (ESESS) (also known as continuous spike-wave of slow sleep (CSWSS) [Carmi et al 2015, Kessi et al 2018].

Cranial nerve functions, sensation, and muscle tone are normal.

No cardiac or structural brain abnormalities have been reported.

The level of 3-methylglutaconate (3-MGC) or 3-methylglutaric acid (3-MGA) in urine does not correlate with the degree of neurologic damage.

Electroretinogram is normal.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

Genotype-phenotype correlations cannot be made due to the limited number of OPA3 pathogenic variants identified to date.

All individuals of Iraqi Jewish origin with Costeff syndrome have the same pathogenic variant (c.143-1G>C); however, phenotypic severity varies, even within the same family.

Nomenclature

Costeff syndrome has also been referred to as "optic atrophy plus syndrome" and "Costeff optic atrophy syndrome."

Prevalence

Costeff syndrome has been reported in more than 40 individuals of Iraqi Jewish origin [Anikster et al 2001], but also in families of Kurdish-Turkish descent [Kleta et al 2002], Afghani descent [Gaier et al 2019], and others. Of note, as the vast majority of affected individuals are still of Iraqi Jewish descent residing in Israel, it must be underscored that some families originate from the Iraqi area, including Iran and Syria. Individuals with Costeff syndrome have also been diagnosed from outside of Israel, including recently in the United States [Author, personal observation].

The carrier rate in Iraqi Jews was initially estimated at 1:10 [Anikster et al 2001]; however, subsequent screening tests showed the carrier rate to be 1:20-1:30 [Author, personal observation].

Genetically Related (Allelic) Disorders

The heterozygous OPA3 pathogenic variants p.Gly93Ser and p.Gln105Glu were reported in two families with autosomal dominant optic atrophy and cataract (OMIM 165300).

Another autosomal dominant phenotype of optic atrophy, cataracts, lipodystrophy/lipoatrophy, and peripheral neuropathy was associated with a de novo OPA3 variant [Bourne et al 2017].

Differential Diagnosis

3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria

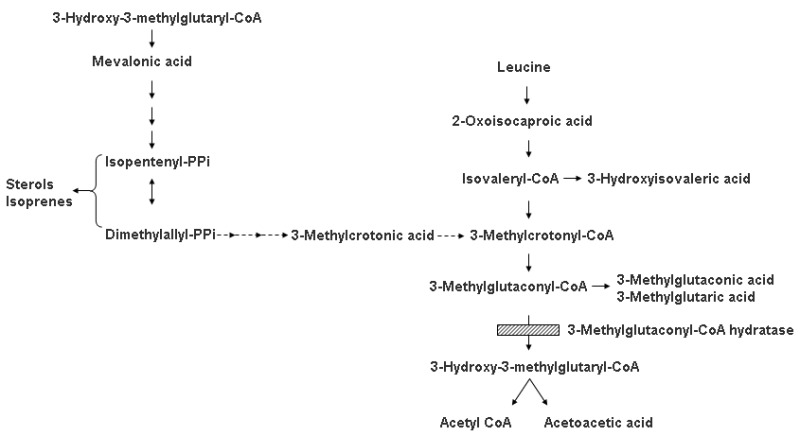

Increased urinary excretion of the branched-chain organic acid 3-methylglutaconate (3-MGC) is a relatively common finding in children investigated for suspected inborn errors of metabolism [Gunay-Aygun 2005]. 3-MGC is an intermediate of leucine degradation and the mevalonate shunt pathway that links sterol synthesis with mitochondrial acetyl-CoA metabolism (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Metabolic pathway diagram showing branched-chain organic acid 3-MGC as an intermediate of leucine degradation and the mevalonate shunt pathway that links sterol synthesis with mitochondrial acetyl-CoA

A classification of inborn errors of metabolism with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (3-MGCA) as the discriminative feature was published by Wortmann et al [2013a] and Wortmann et al [2013b]. Clinical features (Table 2) and biochemical findings of syndromes associated with 3-MGCA vary. Tissues with higher requirements for oxidative metabolism, such as the central nervous system and cardiac and skeletal muscle, are predominantly affected. The only disorder in which the exact source of 3-MGC is known (a block of leucine degradation) is AUH defect, the rarest 3-MGCA, caused by primary deficiency of the mitochondrial enzyme 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase (3-MGCH).

Table 2.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism Associated with 3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria

Clinical Findings of Costeff Syndrome

Behr syndrome. The clinical picture of Behr syndrome is most similar to Costeff syndrome [Copeliovitch et al 2001]. Behr syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by pathogenic variants in OPA1 (OMIM 210000) associated with childhood-onset optic atrophy and spinocerebellar degeneration characterized by ataxia, spasticity, intellectual disability, posterior column sensory loss, and peripheral neuropathy.

Ataxia, an obligatory finding in Behr syndrome, is not seen in approximately half of individuals with Costeff syndrome; conversely, most individuals with Behr syndrome do not manifest extrapyramidal dysfunction, one of the major features of Costeff syndrome. Given that some individuals with Costeff syndrome do not have extrapyramidal dysfunction, it is not possible to distinguish Behr syndrome from Costeff syndrome based on clinical findings alone. Costeff syndrome can be distinguished from Behr syndrome by the presence of elevated excretion of 3-MGC and 3-MGA in urine.

Management

Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis

To establish the extent of disease and needs in an individual diagnosed with Costeff syndrome, the evaluations summarized in Table 3 (if not performed as part of the evaluation that led to the diagnosis) are recommended.

Table 3.

Recommended Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis in Individuals with Costeff Syndrome

Treatment of Manifestations

Treatment is supportive. A multidisciplinary team including a neurologist, orthopedic surgeon, ophthalmologist, biochemical geneticist, and physical therapist is required for the care of affected individuals.

Table 4.

Treatment of Manifestations in Individuals with Costeff Syndrome

Developmental Delay / Intellectual Disability Management Issues

The following information represents typical management recommendations for individuals with developmental delay / intellectual disability in the United States; standard recommendations may vary from country to country.

Ages 0-3 years. Referral to an early intervention program is recommended for access to occupational, physical, speech, and feeding therapy as well as infant mental health services, special educators, and sensory impairment specialists. In the US, early intervention is a federally funded program available in all states that provides in-home services to target individual therapy needs.

Ages 3-5 years. In the US, developmental preschool through the local public school district is recommended. Before placement, an evaluation is made to determine needed services and therapies and an individualized education plan (IEP) is developed for those who qualify based on established motor, language, social, or cognitive delay. The early intervention program typically assists with this transition. Developmental preschool is center based; for children too medically unstable to attend, home-based services are provided.

All ages. Consultation with a developmental pediatrician is recommended to ensure the involvement of appropriate community, state, and educational agencies (US) and to support parents in maximizing quality of life. Some issues to consider:

- IEP services:

- An IEP provides specially designed instruction and related services to children who qualify.

- IEP services will be reviewed annually to determine whether any changes are needed.

- Special education law requires that children participating in an IEP be in the least restrictive environment feasible at school and included in general education as much as possible, when and where appropriate.

- Vision and hearing consultants should be a part of the child's IEP team to support access to academic material.

- PT, OT, and speech services will be provided in the IEP to the extent that the need affects the child's access to academic material. Beyond that, private supportive therapies based on the affected individual's needs may be considered. Specific recommendations regarding type of therapy can be made by a developmental pediatrician.

- As a child enters the teen years, a transition plan should be discussed and incorporated in the IEP. For those receiving IEP services, the public school district is required to provide services until age 21.

- A 504 plan (Section 504: a US federal statute that prohibits discrimination based on disability) can be considered for those who require accommodations or modifications such as front-of-class seating, assistive technology devices, classroom scribes, extra time between classes, modified assignments, and enlarged text.

- Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) enrollment is recommended. DDA is a US public agency that provides services and support to qualified individuals. Eligibility differs by state but is typically determined by diagnosis and/or associated cognitive/adaptive disabilities.

- Families with limited income and resources may also qualify for supplemental security income (SSI) for their child with a disability.

Motor Dysfunction

Gross motor dysfunction

- Physical therapy is recommended to maximize mobility and to reduce the risk for later-onset orthopedic complications (e.g., contractures, scoliosis, hip dislocation).

- Consider use of durable medical equipment and positioning devices as needed (e.g., wheelchairs, walkers, bath chairs, orthotics, adaptive strollers).

- For muscle tone abnormalities including hypertonia or dystonia, consider involving appropriate specialists to aid in management of baclofen, tizanidine, Botox®, anti-parkinsonian medications, or orthopedic procedures.

Fine motor dysfunction. Occupational therapy is recommended for difficulty with fine motor skills that affect adaptive function such as feeding, grooming, dressing, and writing.

Oral motor dysfunction should be assessed at each visit and clinical feeding evaluations and/or radiographic swallowing studies should be obtained for choking/gagging during feeds, poor weight gain, frequent respiratory illnesses or feeding refusal that is not otherwise explained. Assuming that the individual is safe to eat by mouth, feeding therapy (typically from an occupational or speech therapist) is recommended to help improve coordination or sensory-related feeding issues. Feeds can be thickened or chilled for safety. When feeding dysfunction is severe, an NG-tube or G-tube may be necessary.

Communication issues. Consider evaluation for alternative means of communication (e.g., augmentative and alternative communication [AAC]) for individuals who have expressive language difficulties. An AAC evaluation can be completed by a speech-language pathologist who has expertise in the area. The evaluation will consider cognitive abilities and sensory impairments to determine the most appropriate form of communication. AAC devices can range from low-tech, such as picture exchange communication, to high-tech, such as voice-generating devices. Contrary to popular belief, AAC devices do not hinder verbal development of speech, but rather support optimal speech and language development.

Surveillance

Table 5.

Recommended Surveillance for Individuals with Costeff Syndrome

Agents/Circumstances to Avoid

The following should be avoided:

- Tobacco and alcohol use

- Medications known to impair mitochondrial function

Evaluation of Relatives at Risk

See Genetic Counseling for issues related to testing of at-risk relatives for genetic counseling purposes.

Therapies Under Investigation

Search ClinicalTrials.gov in the US and EU Clinical Trials Register in Europe for access to information on clinical studies for a wide range of diseases and conditions. Note: There may not be clinical trials for this disorder.

Genetic Counseling

Genetic counseling is the process of providing individuals and families with information on the nature, mode(s) of inheritance, and implications of genetic disorders to help them make informed medical and personal decisions. The following section deals with genetic risk assessment and the use of family history and genetic testing to clarify genetic status for family members; it is not meant to address all personal, cultural, or ethical issues that may arise or to substitute for consultation with a genetics professional. —ED.

Mode of Inheritance

Costeff syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

Risk to Family Members

Parents of a proband

- The parents of an affected child are obligate heterozygotes (i.e., presumed to be carriers of one OPA3 pathogenic variant based on family history).

- Molecular genetic testing is recommended for the parents of a proband to confirm that both parents are heterozygous for an OPA3 pathogenic variant and to allow reliable recurrence risk assessment. (De novo variants are known to occur at a low but appreciable rate in autosomal recessive disorders [Jónsson et al 2017].)

- Heterozygotes (carriers) are asymptomatic and are not at risk of developing the disorder.

Sibs of a proband

- If both parents are known to be heterozygous for an OPA3 pathogenic variant, each sib of an affected individual has at conception a 25% chance of being affected, a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of being unaffected and not a carrier. Note: Intrafamilial clinical variability is observed in Costeff syndrome; a sib who inherits biallelic OPA3 pathogenic variants may be more or less severely affected than the proband.

- Heterozygotes (carriers) are asymptomatic and are not at risk of developing the disorder.

Offspring of a proband

- Unless an individual with Costeff syndrome has children with an affected individual or a carrier, the offspring of a proband will be obligate heterozygotes (carriers) for a pathogenic variant in OPA3.

- Note: The carrier frequency in individuals of Iraqi Jewish descent was formerly estimated at 1:10 [Anikster et al 2001]; it now appears to be 1:20-1:30.

Other family members. Each sib of the proband's parents is at a 50% risk of being a carrier of an OPA3 pathogenic variant.

Carrier (Heterozygote) Detection

Carrier testing for at-risk relatives requires prior identification of the OPA3 pathogenic variants in the family.

Carrier testing in individuals of Iraqi Jewish origin relies on targeted analysis for the c.143-1G>C pathogenic variant.

Note: Because carriers have normal urinary excretion of 3-methylglutaric acid (3-MGA) and 3-methylglutaconate (3-MGC), carrier status cannot be determined using biochemical genetic testing.

Related Genetic Counseling Issues

Family planning

- The optimal time for determination of genetic risk and discussion of the availability of prenatal/preimplantation genetic testing is before pregnancy.

- It is appropriate to offer genetic counseling (including discussion of potential risks to offspring and reproductive options) to young adults who are affected, are carriers, or are at risk of being carriers.

Prenatal Testing and Preimplantation Genetic Testing

Molecular genetic testing. Once the OPA3 pathogenic variants have been identified in an affected family member, prenatal testing for a pregnancy at increased risk and preimplantation genetic testing are possible.

Biochemical genetic testing. Measurement of 3-MGC and 3-MGA in amniotic fluid is not reliable.

Differences in perspective may exist among medical professionals and within families regarding the use of prenatal testing. While most centers would consider use of prenatal testing to be a personal decision, discussion of these issues may be helpful.

Resources

GeneReviews staff has selected the following disease-specific and/or umbrella support organizations and/or registries for the benefit of individuals with this disorder and their families. GeneReviews is not responsible for the information provided by other organizations. For information on selection criteria, click here.

- Costeff Support GroupSheba Medical CenterTel Hashomer 52621IsraelPhone: +9723530 5017Fax: +9723530 2658Email: roma40@012.net.il

- National Library of Medicine Genetics Home Reference

- Metabolic Support UKUnited KingdomPhone: 0845 241 2173

- Organic Acidemia AssociationPhone: 763-559-1797Email: info@oaanews.org

Molecular Genetics

Information in the Molecular Genetics and OMIM tables may differ from that elsewhere in the GeneReview: tables may contain more recent information. —ED.

Table A.

Costeff Syndrome: Genes and Databases

Table B.

OMIM Entries for Costeff Syndrome (View All in OMIM)

Molecular Pathogenesis

OPA3 encodes a 179-amino acid (20-kd) protein that contains a mitochondrial targeting peptide, NRIKE, at amino acid residues 25-29 and is predicted to be exported to the mitochondrion [Anikster et al 2001]. It is ubiquitously expressed, with highest expression in skeletal muscle and kidney. In the brain, the cerebral cortex, medulla, cerebellum, and frontal lobe have slightly increased expression [Anikster et al 2001].

The resulting lack of mRNA expression manifests as the absence of an OPA3 band on a northern blotting of fibroblasts from affected individuals and as an inability to amplify OPA3 from the blood of affected individuals [Anikster et al 2001].

The effect of the OPA3 pathogenic variants on cell function is unknown. Homozygous acceptor splice site variant c.143-1G>C in OPA3 with loss of function leads to typical Costeff syndrome.

Mechanism of disease causation. OPA3 loss of function

OPA3-specific laboratory technical considerations. In the literature, the number of exons of OPA3 may be given as two or three. The issue is one of alternative splicing; see Lam et al [2014] for a succinct explanation.

Table 6.

Notable OPA3 Pathogenic Variants

References

Literature Cited

- Anikster Y, Kleta R, Shaag A, Gahl WA, Elpeleg O. Type III 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (optic atrophy plus syndrome, or Costeff optic atrophy syndrome): identification of the OPA3 gene and its founder mutation in Iraqi Jews. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1218–24. [PMC free article: PMC1235533] [PubMed: 11668429]

- Barth PG, Valianpour F, Bowen VM, Lam J, Duran M, Vaz FM, Wanders RJ. X-linked cardioskeletal myopathy and neutropenia (Barth syndrome): an update. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;126A:349–54. [PubMed: 15098233]

- Bourne SC, Townsend KN, Shyr C, Matthews A, Lear SA, Attariwala R, Lehman A, Wasserman WW, van Karnebeek C, Sinclair G, Vallance H, Gibson WT. Optic atrophy, cataracts, lipodystrophy/lipoatrophy, and peripheral neuropathy caused by a de novo OPA3 mutation. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2017;3:a001156. [PMC free article: PMC5171695] [PubMed: 28050599]

- Carmi N, Lev D, Leshinsky-Silver E, Anikster Y, Blumkin L, Kivity S, Lerman-Sagie T, Zerem A. Atypical presentation of Costeff syndrome-severe psychomotor involvement and electrical status epilepticus during slow wave sleep. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19:733–6. [PubMed: 26190011]

- Copeliovitch L, Katz K, Arbel N, Harries N, Bar-On E, Soudry M. Musculoskeletal deformities in Behr syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:512–4. [PubMed: 11433166]

- Davey KM, Parboosingh JS, McLeod DR, Chan A, Casey R, Ferreira P, Snyder FF, Bridge PJ, Bernier FP. Mutation of DNAJC19, a human homologue of yeast inner mitochondrial membrane co-chaperones, causes DCMA syndrome, a novel autosomal recessive Barth syndrome-like condition. J Med Genet. 2006;43:385–93. [PMC free article: PMC2564511] [PubMed: 16055927]

- Elpeleg ON, Costeff H, Joseph A, Shental Y, Weitz R, Gibson KM. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria in the Iraqi-Jewish "optic atrophy plus" (Costeff) syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36:167–72. [PubMed: 7510656]

- Gaier ED, Sahai I, Wiggs JL, McGeeney B, Hoffman J, Peeler CE. Novel homozygous OPA3 mutation in an Afghani family with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type III and optic atrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019;40:570–3. [PMC free article: PMC7050282] [PubMed: 31928268]

- Gunay-Aygun M. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria: a common biochemical marker in various syndromes with diverse clinical features. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;84:1–3. [PubMed: 15719488]

- Ho G, Walter JH, Christodoulou J. Costeff optic atrophy syndrome: New clinical case and novel molecular findings. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31 Suppl 2:S419–23. [PubMed: 18985435]

- Ijlst L, Loupatty FJ, Ruiter JP, Duran M, Lehnert W, Wanders RJ. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type I is caused by mutations in AUH. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1463–6. [PMC free article: PMC378594] [PubMed: 12434311]

- Illsinger S, Lucke T, Zschocke J, Gibson KM, Das AM. 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type I in a boy with fever-associated seizures. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:213–5. [PubMed: 15033206]

- Jónsson H, Sulem P, Kehr B, Kristmundsdottir S, Zink F, Hjartarson E, Hardarson MT, Hjorleifsson KE, Eggertsson HP, Gudjonsson SA, Ward LD, Arnadottir GA, Helgason EA, Helgason H, Gylfason A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Rafnar T, Frigge M, Stacey SN, Th Magnusson O, Thorsteinsdottir U, Masson G, Kong A, Halldorsson BV, Helgason A, Gudbjartsson DF, Stefansson K. Parental influence on human germline de novo mutations in 1,548 trios from Iceland. Nature. 2017;549:519–22. [PubMed: 28959963]

- Kessi M, Peng J, Yang L, Xiong J, Duan H, Pang N, Yin F. Genetic etiologies of the electrical status epilepticus during slow wave sleep: systematic review. BMC Genet. 2018;19:40. [PMC free article: PMC6034250] [PubMed: 29976148]

- Kleta R, Skovby F, Christensen E, Rosenberg T, Gahl WA, Anikster Y. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type III in a non-Iraqi-Jewish kindred: clinical and molecular findings. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:201–6. [PubMed: 12126933]

- Kovacs-Nagy R, Morin G, Nouri MA, Brandau O, Saadi NW, Nouri MA, van den Broek F, Prokisch H, Mayr JA, Wortmann SB. HTRA2 defect: a recognizable inborn error of metabolism with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria as discriminating feature characterized by neonatal movement disorder and epilepsy-report of 11 patients. Neuropediatrics. 2018;49:373–8. [PubMed: 30114719]

- Lam C, Gallo LK, Dineen R, Ciccone C, Dorward H, Hoganson GE, Wolfe L, Gahl WA, Huizing M. Two novel compound heterozygous mutations in OPA3 in two siblings with OPA3-related 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2014;1:114–23. [PMC free article: PMC3987911] [PubMed: 24749080]

- Sofer S, Schweiger A, Blumkin L, Yahalom G, Anikster Y, Lev D, Ben-Zeev B, Lerman-Sagie T, Hassin-Baer S. The neuropsychological profile of patients with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type III, Costeff syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168B:197–203. [PubMed: 25657044]

- Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Chapman M, Evans K, Azevedo L, Hayden M, Heywood S, Millar DS, Phillips AD, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): optimizing its use in a clinical diagnostic or research setting. Hum Genet. 2020;139:1197–207. [PMC free article: PMC7497289] [PubMed: 32596782]

- Sweetman L, Williams JC. Branched chain organic acidurias. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. Vol 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:2137-40.

- Wortmann SB, Duran M, Anikster Y, Barth PG, Sperl W, Zschocke J, Morava E, Wevers RA. Inborn errors of metabolism with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria as discriminative feature: proper classification and nomenclature. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013a;36:923–8. [PubMed: 23296368]

- Wortmann SB, Kluijtmans LA, Rodenburg RJ, Sass JO, Nouws J, van Kaauwen EP, Kleefstra T, Tranebjaerg L, de Vries MC, Isohanni P, Walter K, Alkuraya FS, Smuts I, Reinecke CJ, van der Westhuizen FH, Thorburn D, Smeitink JA, Morava E, Wevers RA. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria-lessons from 50 genes and 977 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013b;36:913–21. [PubMed: 23355087]

- Yahalom G, Anikster Y, Huna-Baron R, Hoffmann C, Blumkin L, Lev D, Tsabari R, Nitsan Z, Lerman SF, Ben-Zeev B, Pode-Shakked B, Sofer S, Schweiger A, Lerman-Sagie T, Hassin-Baer S. Costeff syndrome: clinical features and natural history. J Neurol. 2014;261:2275–82. [PubMed: 25201222]

Chapter Notes

Author Notes

Readers are welcome to contact Dr Anikster with questions at the Metabolic Disease Unit.

Phone: +97235305017

Fax: +97235305018

Author History

Yair Anikster, MD, PhD (2006-present)

William A Gahl, MD, PhD; National Institutes of Health (2006-2013)

Meral Gunay-Aygun, MD; National Institutes of Health (2006-2020)

Marian Huizing, PhD; National Institutes of Health (2013-2020)

Revision History

- 30 April 2020 (bp) Comprehensive update posted live

- 19 December 2013 (me) Comprehensive update posted live

- 31 March 2009 (me) Comprehensive update posted live

- 28 July 2006 (me) Review posted live

- 27 April 2006 (mga) Original submission

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Publication History

Initial Posting: July 28, 2006; Last Update: April 30, 2020.

Copyright

GeneReviews® chapters are owned by the University of Washington. Permission is hereby granted to reproduce, distribute, and translate copies of content materials for noncommercial research purposes only, provided that (i) credit for source (http://www.genereviews.org/) and copyright (© 1993-2024 University of Washington) are included with each copy; (ii) a link to the original material is provided whenever the material is published elsewhere on the Web; and (iii) reproducers, distributors, and/or translators comply with the GeneReviews® Copyright Notice and Usage Disclaimer. No further modifications are allowed. For clarity, excerpts of GeneReviews chapters for use in lab reports and clinic notes are a permitted use.

For more information, see the GeneReviews® Copyright Notice and Usage Disclaimer.

For questions regarding permissions or whether a specified use is allowed, contact: ude.wu@tssamda.

Publisher

University of Washington, Seattle, Seattle (WA)

NLM Citation

Anikster Y. Costeff Syndrome. 2006 Jul 28 [Updated 2020 Apr 30]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.