Abbreviations

- AGREE

Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation

- CRD

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- MFAC

Modified Functional Ambulation Categories

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RNAO

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario

Context and Policy Issues

Hospitals operate with the primary goal of improving the health of individuals who seek health care services. Despite this, a small proportion of patients experience unintended harm during their hospital stay; 37% of these adverse events are considered preventable.1,2 Older adults are particularly vulnerable to adverse events during their hospital stay as they tend to be frailer and have more comorbidities than their younger counterparts.2 In particular, falls in the hospital setting are three times more likely than in the community.3

The ideology of restraint use is to prevent patients from harming themselves (e.g., patient is a high risk for sustaining a fall) or others (e.g., patient displays dangerous behaviour towards care staff or other patients).4,5 Restraints are often described as a chemical or a physical restraint.4 Chemical restraints can be thought of as pharmacologic drugs, such as antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.6 Physical restraints are “mechanical devices, materials, or equipments which restrict freedom of movement or normal access to one’s body.”7 Examples of physical restraints include wrist and ankle restraints, bed rails, lap belts, and chairs with table trays that prevent patients from rising.8

Restraint use has been ethically debated for decades, largely because it inhibits patients’ autonomy and dignity.5,9,10 Studies conducted in the long-term care setting found no evidence that restraint use reduces falls and restraints may increase the presence of pressure ulcers.8,11–15 Moreover, the Government of Ontario released the Patient Restraints Minimization Act in 2011 to “minimize the use of restraints on patients and to encourage hospitals and facilities to use alternative methods, whenever possible, when it is necessary to prevent serious bodily harm by a patient to himself or herself or to others.”16 Despite this, evidence around clinical effectiveness for the use and avoidance of physical restraints among older adults in the hospital setting is less clear. Synthesized evidence about physical restraints within the hospital setting is required to inform best practices.

Thus, this report aims to summarize the evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness and evidence-based guidelines for the use or avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness regarding the use of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults?

What is the clinical effectiveness regarding the avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults?

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the use or avoidance of physical restraint among hospitalized older adults?

Key Findings

One relevant systematic review was identified on the use of physical restraints, specifically the use of bed rails for preventing falls, among hospitalized older adults. This review did not uncover any relevant studies; thus, no conclusions regarding the use of restraints can be provided.

Evidence of limited quality from two clinical studies on the avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults suggested that reducing restraint use may shorten average length of stay, especially for older patients who are cognitively impaired. Programs aimed to reduce physical restraint use improved mobility and activities of daily living outcomes, but did not significantly affect fall or mortality rates.

One Canadian evidence-based guideline was identified, which recommends using principles of least restraint/restraint as a last resort when caring for older adults.

Given the limited availability and low quality of evidence, the effectiveness and use of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults remains uncertain, but reduced restraint use seems to be preferred.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, and guidelines. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2012 and January 30, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Citations were excluded if they: (i) did not meet the selection criteria outlined in ; (ii) were duplicate publications; or (iii) were published prior to 2012. Guidelines with unclear methodology were also excluded. Studies that used restraints as a treatment intervention (e.g., modified constraint-induced movement therapy) for those who have recently experienced a stroke were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included clinical studies were critically appraised by one reviewer using Downs and Black checklist17 and the guideline was assessed with the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument.18 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

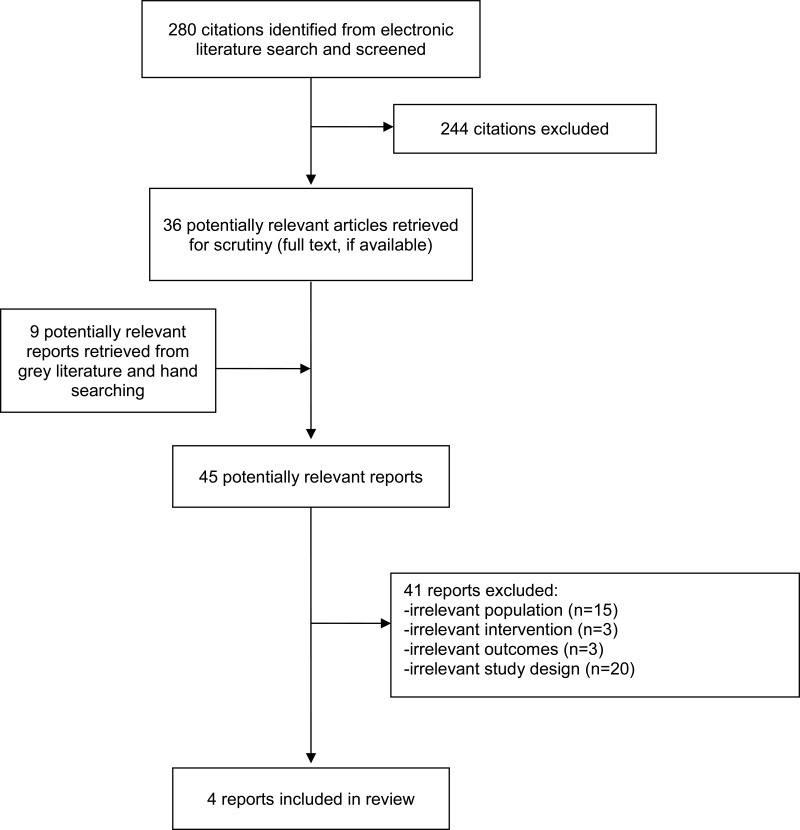

A total of 280 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 244 citations were excluded and 36 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Nine potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 41 publications were excluded for various reasons, and four publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised one systematic review, two clinical studies and one evidence-based guideline. Appendix 1 presents the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)19 flowchart of the study selection.

Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

One systematic review10 and two single-centre studies20,21 of clinical effectiveness were identified.20,21 The systematic review did not uncover any relevant studies after searching 13 databases for literature published in three different languages from January 1, 1980 to March 31, 2017.10 The review considered the following study designs for inclusion: randomized controlled trials, before and after studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, descriptive studies, case series/reports and expert-opinion.

The two clinical studies used different methodologies: a quasi-experimental stepped-wedge trial20 and a non-randomized controlled before-and-after study.21 A stepped-wedge trial involves “random and sequential crossover of clusters from control to intervention until all clusters are exposed.”22 A controlled before-and-after study is a study in which “observations are made before and after the implementation of an intervention, both in a group that receives the intervention and in a control group that does not.”23

One evidence-based guideline was identified, which was produced by the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) International Affairs and Best Practice Guidelines Centre.24 This guideline focuses on the assessment and care of older adults with delirium, dementia, and/or depression. Relevant to this report, the guideline provides recommendations on the topic of restraint use for older adults. For restraint use specifically, the guideline bases its recommendations on level V evidence, which is described as “evidence obtained from expert opinion or committee reports, and/or clinical experiences of respected authorities.”24 Since evidence is ranked based on seven categories (i.e., Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, III, IV, V), this recommendation is ranked the lowest level of evidence.24

Country of Origin

The body of evidence originated from Canada (one clinical study,20 one guideline24), Portugal (one systematic review10), and China (one clinical study21).

Patient Population

The systematic review considered literature of hospitalized adults who were 65 years of age or older with any clinical condition in a non-intensive care unit.10 This review, however, did not retrieve any relevant studies.

Both clinical studies examined older adults (65+ years old) admitted to a hospital.20,21 There were no restrictions on sex or gender reported. The stepped-wedge trial included patients who were admitted during each of the four monthly audits.20 No details regarding the number of patients included or basic patient demographics (e.g., percentage male, cognition status, frailty status) were described. The controlled before-and-after study included 1,946 older adult patients (2,000 patient episodes) within a convalescent medical ward, with and without cognitive impairment.21 An episode was described as an “episode of care for a particular patient admitted to and discharged from a hospital ward.”21 Patients included before the introduction of the restraint reduction program comprised 958 patient episodes randomly selects from medical records of the year 2007 (control group; mean age 79.40 ± 10.05 years). Patients included after the introduction of the restraint reduction program comprised 988 patient episodes randomly selects from medical records of the year 2009 (intervention group; mean age 79.58 ± 10.81 years).

The guideline focuses on the assessment and care of older adults with delirium, dementia, and/or depression for nurses, health care providers, and health care administrators working in a range of community and health care settings, including the hospital.24

Interventions and Comparators

For the systematic review, the intervention of interest the use of bedrails as a restraint to prevent falls among hospitalized older adults in non-intensive care units.10 The comparator of interest was no use of bedrails or any type of physical restraints.

For the stepped-wedge trial, the intervention consisted of the development of opinion leaders among the nursing leadership, education and training of physicians and unit nurses, and implementation of least restraint rounds.20 This intervention was implemented sequentially to the four involved medical wards over four time periods at one-month intervals. Thus, all four wards eventually received the intervention, but the time point at which it was implemented varied between wards. The comparator for this study was usual care, which may have included the use of restraints, using data from the wards before the intervention was applied. Authors described the following restraints could be used within their hospital: seat belts, wrist or ankle restraints, waist or jacket restraints, chair trays when used outside of food service, chairs reclined to prevent individual from rising out of chair, bed rails in upright position.20

For the controlled before-and-after study, the intervention consisted of a restraint reduction program.21 The comparator for this study was usual care, which may have included the use of restraints, prior to the implementation of the restraint reduction program. Authors described the following restraints could be used within their hospital: hand holder, safety vest, abdominal belt, seat belt, foot holder, table top, bilateral bed rails.21

The use of restraints section of the guideline examines the principles of least restraint/restraint as a last resort.24

Outcomes

For the systematic review, the outcomes of interest were number of patients who fell or number of falls per patient (primary outcomes) and number of head trauma, bone fractures or soft tissue injuries (secondary outcomes).10

The clinical studies investigated the following clinical outcomes: falls,20,21 length of stay,21 mortality,21 mobility using the Modified Functional Ambulation Categories (MFAC) Tool,21 and ability to perform activities of daily living using the Modified Barthel Index.21 The MFAC tool used a seven-point classification scale, where one equates to a patient who is bed-bound and seven equates to patient who is an independent outdoor walker. The Modified Barthel Index score is ascertained by an occupational therapist (on admission and discharge). The therapist rates the patient’s ability to perform 10 activities of daily living: personal hygiene, bathing, feeding, toilet, stair climbing, dressing, bowel control, bladder control, ambulation, and chair/bed transfer. The maximum score a patient can receive is 100, which signifies total independence.21

The guideline considers how restraint use may increase the risk for delirium.24 The guideline also considers how restraints may be used for patients with dementia when suffering from pronounced and potentially harmful agitation.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 3.

Systematic Review

The systematic review authors published a protocol prior to the conduct of the review, included components of PICO in their eligibility criteria, provided their complete search strategy, and conducted a comprehensive literature search of 13 databases and grey literature. All screening was performed in duplicate and reasons for excluding studies are provided with the accompanying list of excluded studies in the appendix.

Clinical Studies

The two included clinical studies have a number of strengths and limitations. Both clinical studies clearly described their objectives, intervention, comparator, outcomes, and main findings.20,21 For both studies, patients in the intervention and control groups came from the same institution.20,21 One study is described as a quasi-experimental randomized stepped-wedge trial design but the randomization described was related to randomly staggering the medical units to the intervention versus randomly assigning medical units to be included in the trial.20 Due to the stepped-wedge trial design of this study, the number of medical units, and presumably patients, representing each group varied at each time point of outcome ascertainment.20 This same study did not provide details on the number of patients included in the study nor did they describe details about the patients’ baseline characteristics.20 These details are necessary in order to determine whether patient demographic characteristics were balanced between groups, and to assess the generalizability of the study findings. Conversely, the other clinical study randomly selected patients from the year before and the year after the implementation of the intervention, clearly described the patient population, and performed subgroup analyses to distinguish intervention effects for patients with and without cognitive impairment (cognitive impairment is a recognized risk factor for restraint use).21 It should be recognized, however, that due to the study’s inherent pre-post design, the patients from each group were from a different time period (i.e., 2007 versus 2009). Sampling the intervention group from a different time period than the control group increases the study’s risk of bias, since we do not know how the different time periods affect changes in the outcome measures.25 This clinical study also used validated tools, when applicable, to ascertain clinical outcomes of interest.21 When examining the external validity of the findings, it is unclear whether the participants were representative of the source population for either study.20,21 When deducing the internal validity of either clinical study, neither study mentioned blinding in their methods.20,21 Though it may not be possible to blind patients to restraint use, it could be possible to blind the investigators who were analyzing the data between groups. If blinding was not performed in any capacity, the authors could have included this as a limitation in the discussion for improved transparency. The authors did not describe sample size calculations to determine statistical power;20,21 however, one study mentioned in the discussion that the study may not be sufficiently powered.20

Guidelines

The included guideline24 meets the majority of the required criteria of the AGREE II18 tool. Strengths of the guidelines include the overall objectives and populations to whom the guidelines apply are specifically described; guideline development groups comprise a panel of individuals with expertise in delirium, dementia and/or depression across different health care settings; the target users of the guidelines are clearly defined; systematic methods are used to search for evidence; the criteria for selecting the evidence, the strengths and limitations of the body of evidence, and the methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described; the guideline is externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication; a procedure for updating the guideline is provided; and the recommendations are specific and unambiguous. These features may increase the reliability of the recommendations as they demonstrate sound methodology and make these publications less prone to biases. However, different treatment options, aside from restraint use, are not presented. Though the investigators conduct a rigourous approach to uncovering evidence for the guideline, the recommendations for using principles of least restraint are based on low quality of evidence (i.e., expert opinion versus meta-analysis); the deficiency of treatment alternatives may be due to the lack of available published evidence on this particular recommendation. Funding is declared but there is no statement stating the views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline.

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents a table of the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Clinical Effectiveness for the Use of Physical Restraints

One systematic review examined clinical effectiveness for the use of physical restraints (i.e., bed rails). However, no relevant studies were identified from this review; therefore, no summary can be provided.

Clinical Effectiveness for the Avoidance of Physical Restraints

Two studies examined clinical effectiveness for the avoidance of physical restraints. Relevant to this report, one study examined fall rates,20 while the other study examined falls, length of stay, mobility, activities of daily living, and mortality outcomes.21

Falls

Both clinical studies found no significant difference in the rates of falls after the implementation of restraint reduction interventions.20,21

Length of Stay

One study examined how a restraint reduction program would influence patients’ length of stay.21 Patients in the intervention group (i.e., post restraint reduction program) had a significant reduction in average length of stay at the hospital when compared to patients in the control group (i.e., prior to implementation of restraint reduction program).21 When considering the cognition of the patients, those who were cognitively impaired had a significantly shorter length of stay post-intervention; there were no significant differences between intervention and control groups for patients in the cognitively normal subgroup.21

Mobility

The same study that examined length of stay also examined how a restraint reduction program would influence patients’ mobility.21 Patients in the intervention group performed better at mobility testing than control group patients.21 When considering patients’ cognition, these differences remained for patients who were in the cognitively normal subgroup but not for patients in the cognitively impaired subgroup.

Ability to perform Activities of Daily Living

Similar to mobility outcomes, patients from the intervention group from one clinical study performed better at metrics for activities of daily living performance compared to patients in the control group; when considering patients’ cognition, these differences remained for patients who were in the cognitively normal subgroup but not for patients in the cognitively impaired subgroup.21

Mortality

After the implementation of a restraint reduction program, no significant differences were found for mortality outcomes.21

Guidelines

The guideline recommends using principles of least restraint/restraint as a last resort when caring for older adults.24 This recommendation applies to patients who are at risk or have delirium as well as patients with dementia. Notwithstanding, the guideline provides the caveat that health care providers need to be aware of legislation and or policies regarding restraint use that is applicable to their setting and scope of practice.24

Limitations

There are certain limitations to consider when reviewing the report.

The two included clinical studies were not randomized controlled trials. Randomized controlled trials allow for random allocation of participants to either the intervention group or control group with the goal of reducing bias when testing an intervention. Without this, it is difficult to be certain of the true effects and magnitude of benefit for the avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults. Moreover, one study examined the clinical effectiveness for the use of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults. However, this systematic review did not uncover any relevant literature to answer the research question. It is possible that this is due to the established legislation for minimizing restraint use within various jurisdictions/provinces/countries, similar to the law established by the Government of Ontario.16 In addition, it may be possible that more research is available on physical restraint use among older adults in the long-term care setting versus the hospital setting. Finally, the recommendations presented in the evidence-based guideline that are relevant to this report were based on low quality of evidence (i.e., expert opinion) due to the lack of synthesized evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on this topic.24

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

One relevant systematic review examining the clinical effectiveness regarding the use of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults was identified in the search. However, no relevant studies were identified and, therefore, no conclusions regarding the use of restraints can be provided.

Two relevant clinical studies regarding the avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults were identified in the search. These studies provided some evidence that the implementation of a program to reduce restraint use among older patients may shorten average length of stay, improve mobility and activity of daily life outcomes, and may not increase the incidence of falls. There was also some evidence to suggest the avoidance of restraint use may not improve mortality outcomes.

One clinical practice guideline from Canada was identified. Based on expert opinion, this guideline recommends using principles of least restraint/restraint as a last resort when caring for older adults.

Given the limited availability and low quality of evidence, the effectiveness and use of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults remains uncertain. To reduce uncertainty of the clinical effectiveness regarding the use and/or avoidance of physical restraints among hospitalized older adults, further research is required.

References

- 1.

- 2.

Baker

GR, Norton

PG, Flintoft

V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada.

Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170(11):1678–1686. [

PMC free article: PMC408508] [

PubMed: 15159366]

- 3.

AGS/BGS clinical practice guideline: prevention of falls in older persons. New York (NY): American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society; 2010.

- 4.

- 5.

Kruger

C, Mayer

H, Haastert

B, Meyer

G. Use of physical restraints in acute hospitals in Germany: a multi-centre cross-sectional study.

Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(12):1599–1606. [

PubMed: 23768409]

- 6.

Mattison

M, Marcantonio

E, Schmader

K, Gandhi

T, Lin

F. Hospital management of older adults. In: Post

T, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2013:

www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Feb 12.

- 7.

Feng

Z, Hirdes

JP, Smith

TF, et al. Use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: a cross-national study.

Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(10):1110–1118. [

PMC free article: PMC3764453] [

PubMed: 19280680]

- 8.

Berry

S, Kiel

DP, Schmader

K, Sullivan

D. Falls: Prevention in nursing care facilities and the hospital setting. In: Post

T, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017:

www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Feb 12.

- 9.

Sokol

DK. When is restraint appropriate?

BMJ. 2010;341:c4147. [

PubMed: 20685776]

- 10.

Marques

P, Queiros

C, Apostolo

J, Cardoso

D. Effectiveness of bedrails in preventing falls among hospitalized older adults: a systematic review.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(10):2527–2554. [

PubMed: 29035965]

- 11.

Capezuti

E, Evans

L, Strumpf

N, Maislin

G. Physical restraint use and falls in nursing home residents.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(6):627–633. [

PubMed: 8642150]

- 12.

Capezuti

E, Maislin

G, Strumpf

N, Evans

LK. Side rail use and bed-related fall outcomes among nursing home residents.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):90–96. [

PubMed: 12028252]

- 13.

Capezuti

E, Wagner

LM, Brush

BL, Boltz

M, Renz

S, Talerico

KA. Consequences of an Intervention to Reduce Restrictive Side Rail Use in Nursing Homes.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(3):334–341. [

PubMed: 17341234]

- 14.

Castle

NG, Engberg

J. The health consequences of using physical restraints in nursing homes.

Med Care. 2009:1164–1173. [

PubMed: 19786918]

- 15.

Haut

A, Köpke

S, Gerlach

A, Mühlhauser

I, Haastert

B, Meyer

G. Evaluation of an evidence-based guidance on the reduction of physical restraints in nursing homes: a cluster-randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN34974819].

BMC Geriatr. 2009;9(1):42. [

PMC free article: PMC2749852] [

PubMed: 19735564]

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 20.

Enns

E, Rhemtulla

R, Ewa

V, Fruetel

K, Holroyd-Leduc

JM. A controlled quality improvement trial to reduce the use of physical restraints in older hospitalized adults.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):541–545. [

PubMed: 24517583]

- 21.

Kwok

T, Bai

X, Chui

MY, et al. Effect of physical restraint reduction on older patients’ hospital length of stay.

J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):645–650. [

PubMed: 22763142]

- 22.

Hemming

K, Haines

TP, Chilton

PJ, Girling

AJ, Lilford

RJ. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting.

BMJ. 2015;350:h391. [

PubMed: 25662947]

- 23.

- 24.

- 25.

What study designs should be included in an EPOC review and what should they be called?

EPOC Resources for review authors. Oxford (GB): Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group, Cochrane

2017:

https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 2019 Feb 28.

- 26.

Non-pharmaceutical management of depression in adults.

(SIGN national clinical guideline no. 114). Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN); 2010:

https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign114.pdf. Accessed 2019 Feb 12.

- 27.

Pati

D. A framework for evaluating evidence in evidence-based design.

HERD. 2011;4(3):50–71. [

PubMed: 21866504]

- 28.

- 29.

Moreau

C, Delval

A, Defebvre

L, et al. Methylphenidate for gait hypokinesia and freezing in patients with Parkinson’s disease undergoing subthalamic stimulation: a multicentre, parallel, randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(7):589–596. [

PubMed: 22658702]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Review

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Designs and Numbers of Primary Studies Included | Population Characteristics | Intervention, Comparator | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Marques, 2017,10 Portugal | 0 studies included | Hospitalized adults, 65 years and older with any clinical condition in a non-intensive care unit | Intervention: use of bedrails as a restraint to prevent falls Comparator: no use of bedrails or any type of physical restraints | Primary outcomes: number of patients who fell or number of falls per patient Secondary outcomes: number of head trauma, bone fractures or soft tissue injuries |

Table 3Characteristics of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Designs | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparators | Relevant Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Enns, 2014,20 Canada | Quasi-experimental randomized* stepped-wedge trial | Older adults (65+ years old) admitted to study units evaluated during monthly restraint audits | Intervention: multicomponent team-focused approach aimed at decreasing physical restraints Comparator: usual care, including restraint use (i.e., seat belts, wrist or ankle restraints, waist or jacket restraints, chair trays when using outside of food service, chairs reclined to prevent individual from rising out of chair, bed rails in upright position) | Falls during each 1-month period, for 4 months total |

| Kwok, 2012,21 China | Non-randomized controlled before-and-after study | n = 1,946 older adult patients comprising 2,000 patient episodes within a convalescent medical ward, with and without cognitive impairment (961 men, 985 women) Intervention: 988 patient episodes that occurred in the year 2009, after the introduction of the restraint reduction program; mean age: 79.58 (SD = 10.81) years Comparator: 958 patients episodes that occurred in the year 2007, before the introduction of the restraint reduction program; mean age: 79.40 (SD = 10.05) years | Intervention: restraint reduction program Comparator: usual care, including restraint use (i.e., hand holder, safety vest, abdominal belt, seat belt, foot holder, table top, bilateral bed rails) | Length of stay Mobility Ability to perform ADLs Fall incident Mortality Length of follow-up: Not applicable |

- *

randomization described is related to randomly staggering the medical units to the intervention

ADLs = activities of daily life; SD = standard deviation

Table 4Characteristics of Included Guideline

View in own window

| Intended Users, Target Population | Intervention and Practice Considered | Relevant Outcomes Considered | Evidence Collection, Selection, and Synthesis | Evidence Quality Assessment | Recommendations Development and Evaluation | Guideline Validation |

|---|

| RNAO International Affairs and Best Practice Guidelines, 201624 |

|---|

Nurses and health care providers working with older adults who have delirium, dementia, and/or depression in a range of community and health care settings Health care administrators in a range of community and health care settings | Relevant to this report, principles of least restraint | Delirium risk Behaviour outcomes for patients with dementia | Conducted a systematic review to capture relevant peer-reviewed literature and guidelines published between January 2009 and March 2015 Created 1 guideline and provided recommendation based on 3 levels: (i) practice, (ii) education, and (iii) organization and policy recommendation | Quality assessment adapted from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN26 and Pati, S2011)27 | Expert panel of individuals with expertise in delirium, dementia and/or depression across different health care settings (i.e., acute care, long-term care, home health care, mental health, and in the community in primary care and family health teams). Focus: “…provision of effective, compassionate, and dignified care, and on the management of presenting signs, symptoms, and behaviours.”24 | Guideline provided the following disclosure: “This Guideline is the result of the RNAO Guideline development team and expert panel’s work to integrate the most current and best evidence, and ensure the validity, appropriateness, and safety of the Guideline recommendations with supporting evidence and/or expert panel consensus”24 |

RNAO = Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; SIGN = Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Review using AMSTAR 228

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Marques, 201710 |

|---|

The authors published a protocol for their systematic review prior to the conduct of the review Research question/inclusion criteria for the review included the components of PICO Complete search strategy provided, multiple databases and grey literature searched Screening was performed in duplicate, and a third reviewer was involved to assess relevancy of papers that were closest to meeting inclusion criteria Reasons for excluding studies provided with the accompanying list of excluded studies Review authors reported no conflicts of interest

|

|

Table 6Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies using Downs and Black29

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Enns, 201420 |

|---|

Objectives, intervention, comparator, and main outcomes of the study clearly described Patients in both groups from the same institution Appropriate statistical tests used to assess outcomes Main findings of the study adequately described Actual probability values (P values) reported for outcome of interest Due to the type of outcome being assessed (i.e., falls), adverse events reported Funding for the study clearly stated and authors declared no conflicts of interest

|

Due to the stepped-wedge trial design of this study, the number of medical units, and presumably patients, representing each group varied at each time point of outcome ascertainment Number of participants included and the characteristics of the study population is not described Estimates of the random variability not provided Study is described as a quasi-experimental randomized stepped-wedge trial design but randomization described is related to randomly staggering the medical units to the intervention versus randomly assigning medical units to be included in the trial No mention of evaluators, health care staff, patients and/or family members being blinded to treatment allocations It is unclear whether the participants were representative of the source population It is unclear if the staff, places, and facilities where the patients were treated were representative of the treatment the majority of the patients receive Sample size for statistical power not calculated

|

| Kwok, 201221 |

|---|

Objectives, intervention, comparator, and main outcomes of the study clearly described When applicable, outcomes of interest graded using a recognized scale (i.e., MFAC, Barthel Index) Patients in both groups from the same institution Patients were randomly selected from the year before and after the implementation of the intervention Appropriate statistical tests used to assess outcomes Characteristics of the study population clearly described Main findings of the study adequately described Authors acknowledged cognitive impairment is a risk factor for restraint use and, therefore, conducted subgroup analyses. Actual probability values (P values) reported for main outcomes that are larger than P < 0. 001 Authors declared they had no funding to disclose Authors declared no conflicts of interest

|

Estimates of the random variability not provided No mention of blinding evaluators who ascertained outcome data Due to the type of study design, randomization and blinding of participants not possible It is unclear whether the participants were representative of the source population It is unclear if the staff, places, and facilities where the patients were treated were representative of the treatment the majority of the patients receive Patients from each group were from a different period of time (i.e., 2007 versus 2009) Sample size for statistical power not calculated

|

MFAC = Modified Functional Ambulation Categories

Table 7Strengths and Limitations of Guideline using AGREE II18

View in own window

| Item | Guideline |

|---|

| RNAO IA BPG 201624 |

|---|

| Domain 1: Scope and Purpose |

|---|

| 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. | ✓ |

| 2. The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described. | ✓ |

| 3. The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described. | ✓ |

| Domain 2: Stakeholder Involvement |

|---|

| 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups. | ✓ |

| 5. The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought. | ✓ |

| 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. | ✓ |

| Domain 3: Rigour of Development |

|---|

| 7. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. | ✓ |

| 8. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. | ✓ |

| 9. The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described. | ✓ |

| 10. The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. | ✓ |

| 11. The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. | ✓ |

| 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. | ✓ |

| 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. | ✓ |

| 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. | ✓ |

| Domain 4: Clarity of Presentation |

|---|

| 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. | ✓ |

| 16. The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented. | ✕ |

| 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. | ✓ |

| Domain 5: Applicability |

|---|

| 18. The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application. | ✓ |

| 19. The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice. | ✓ |

| 20. The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. | ✓ |

| 21. The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria. | ✓ |

| Domain 6: Editorial Independence |

|---|

| 22. The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline. | unclear |

| 23. Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. | ✓ |

IA BPG = International Affairs & Best Practice Guidelines; RNAO = Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 8Summary of Findings Included Systematic Review

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Marques, 201710 |

|---|

| No studies identified. | |

Table 9Summary of Findings of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Enns, 201420 |

|---|

| Falls

| “The reduction in physical restraint use was not shown to increase fall reports on the units. Although information on why restraints were being used was not available, the fact that falls did not increase as physical restraint use decreased is consistent with the literature [2–4,16]” (p 544)20 “In conclusion, an evidence-informed multicomponent teamfocused quality improvement intervention has the potential to decrease the use of physical restraints in older hospitalized adults, which could improve outcomes.” (p 544–45)20

|

| Kwok, 201221 |

|---|

LOS

All patients: P < 0.001; shorter LOS for intervention patients (average = 16.8 days) than control patients (average = 19.5 days) Cognitively Impaired: P < 0.001; shorter LOS for intervention patients (average = 17.8 days) than control patients (average = 23.0 days) Cognitively Normal: NS; a NS shorter LOS for intervention patients (average = 16.0 days) than control patients (average = 16.8 days)

Mobility

Ability to perform ADLs

All patients: P = 0.01; better performance on MBI for intervention patients than control patients Cognitively Impaired: NS Cognitively Normal: P < 0.001; better performance on MBI for intervention patients than control patients

Fall incident

All patients: NS Cognitively Impaired: NS Cognitively Normal: NS

Mortality

All patients: NS Cognitively Impaired: NS Cognitively Normal: NS

| “Physical restraint reduction was associated with significant reduction in average length of stay in convalescent medical wards, especially in the cognitively impaired patients.” (p 645)21 “The physical restraint reduction scheme launched in 2008 at the Department of Medicine and Geriatrics of a convalescent hospital in Hong Kong [China] was effective in reducing the use of physical restraints and this was associated with a significant reduction in average length of hospital stay, especially in the cognitively impaired patients.” (p 649)21

|

ADLs = activities of daily living; LOS = length of stay; MBI = Modified Barthel Index; MFAC = Modified Functional Ambulation Categories; NS = no significant difference

Table 10. Summary of Recommendations in Included Guideline (PDF, 207K)

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Guidelines with Mixed Populations

Protocol for the included systematic review

Marques

P, Queiros

C, Apostolo

J, Cardoso

D. Effectiveness of the use of bedrails in preventing falls among hospitalized older adults: a systematic review protocol.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(6):4–15. [

PubMed: 26455740]

Study investigating the efficacy of a multicomponent intervention

Khan

BA, Calvo-Ayala

E, Campbell

N, et al. Clinical decision support system and incidence of delirium in cognitively impaired older adults transferred to intensive care. Am J Crit Care. 2013

May;22(3):257–262 [

PMC free article: PMC3752665] [

PubMed: 23635936]

Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Summaries

Le

LKD. Restraint: clinician information. Adelaide (AU): The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2018.

Tufanaru

C.

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: reduction of restrictive practices (workforce competency development for older persons services). Adelaide (AU): The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Avoidance of physical restraint use among hospitalized older adults: A review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Feb. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.