NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

30. Pharmacist support

30.1. Introduction

Increasing numbers of patients with multiple co-morbidities are being exposed to large numbers of medications designed to treat each of the conditions from which they may suffer. This, however, is associated with increasing numbers of drug interactions, difficulties with concordance and possible admissions or readmissions associated with drug errors or adverse effects. The introduction of clinical pharmacists has been designed to minimise these difficulties and, in particular, medicines reconciliation has been conducted for many patients to ensure clarity of the drugs prescribed and taken. The presence of a ward based pharmacist is common practice in the UK. However, the precise input required from pharmacy support is still not clear and this question is posed in an attempt to understand the best way in which pharmacy support is used.

30.2. Review question: Do ward-based pharmacists improve outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed acute medical emergency?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

30.3. Clinical evidence

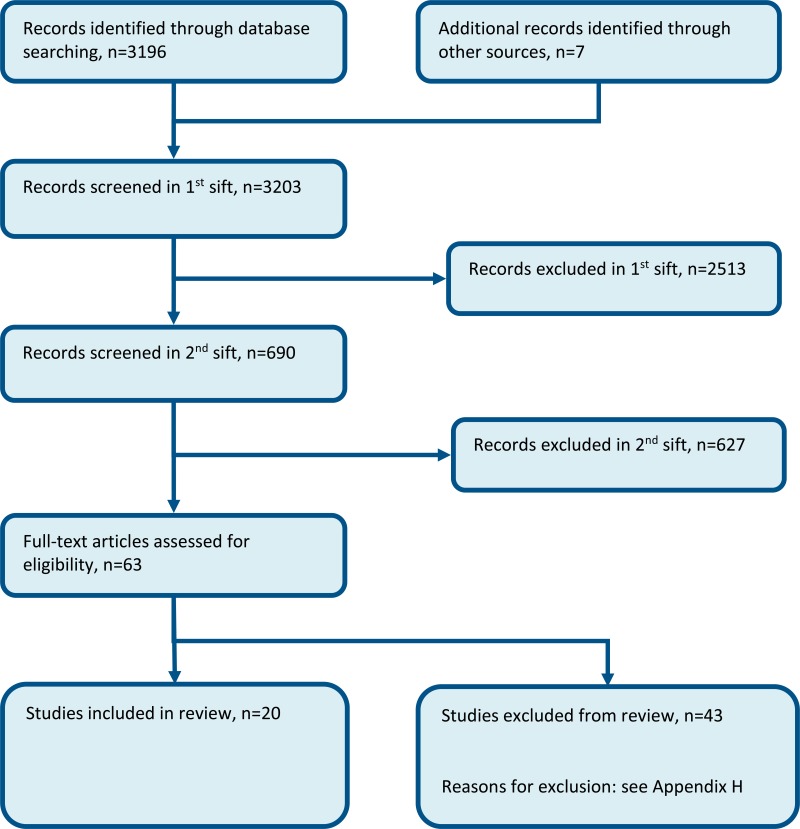

Eighteen studies (20 papers) were included in the review;1,3,8,13,15,17,18,21,31,35,37,39,44,46,57–59,62,69,69,70,70 these were split into 3 strata: regular in-hospital pharmacy support (where the ward-based pharmacist intervention included in-patient monitoring, and typically an admission and discharge service), pharmacist at admission, and pharmacist at discharge. These are summarised respectively in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 5 to Table 7). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Outcomes as reported in studies (not analysable):

- Length of stay: intervention group had on average a 0.3-day shorter stay.

- Readmission: intervention group had a 44% reduced readmission rate.

Outcomes reported that were not analysable

The study by Khalil 201631 reported the total number of medication errors:

- Intervention: 29/56.

- Control: 238/54.

30.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

Seven economic evaluations were identified with the relevant comparison and have been included in this review.13,19–21,29,32,66 Similar to the clinical evidence, these were split into 3 strata: regular ward-based pharmacist support (where the ward-based pharmacist intervention included in-patient monitoring, and typically an admission and discharge service) (n=5), pharmacist at admission (n=1), and pharmacist at discharge (n=1). The studies are summarised in the economic evidence profiles below (Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10) and the economic evidence tables in Appendix F.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

30.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

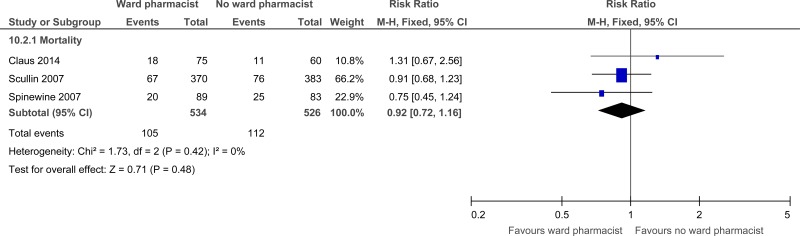

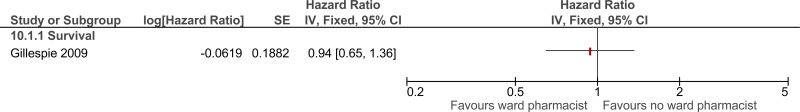

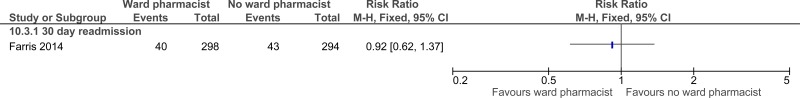

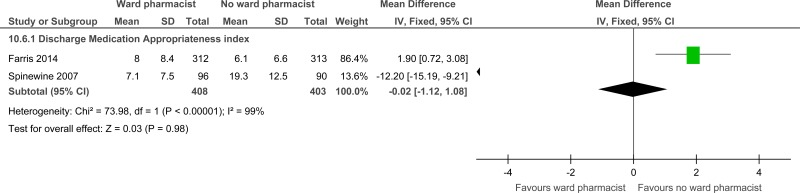

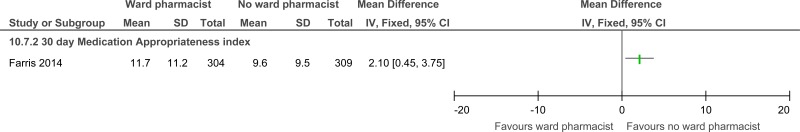

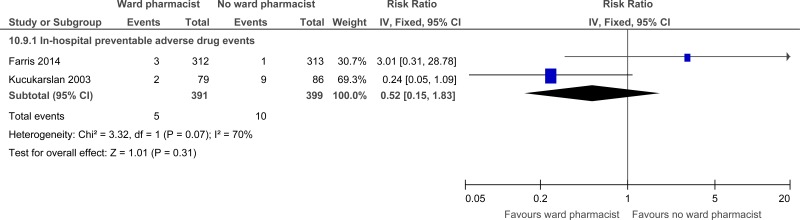

Stratum - Regular in-hospital ward based pharmacy support

Eight randomised controlled trials comprising 2,303 people evaluated the role of regular in-hospital pharmacist support for improving outcomes in secondary care, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that regular in-hospital pharmacist support may provide a benefit for reduced mortality (3 studies, very low quality), reduced preventable adverse drug events in hospital (2 studies, very low quality) and at 90 days follow up (1 study, very low quality) and length of stay (2 studies, moderate quality) and increased patient and/or carer satisfaction at discharge and at one month follow-up (1 study, low quality). The evidence suggested that regular in-hospital pharmacist support has no effect on readmission (1 study, very low quality), adverse drug events at 3 to 6 months post discharge (1 study, very low quality) and admission (4 studies, moderate quality). Evidence suggested no difference between the groups for the outcome of reducing prescribing errors at discharge (2 studies, low quality) ; however there were increased prescribing errors at 30 days in regular in-hospital pharmacist support group compared to no pharmacist support group (1 study quality, moderate quality).

Stratum - Pharmacist at admission

- Six randomised controlled trials comprising 401 people evaluated the role of pharmacists at admission for improving outcomes in secondary care, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that pharmacists at admission may provide benefit for reduced medicine errors (2 studies, low quality), total medication errors within 24 hours of admission (1 study, moderate quality) and physician agreement (1 study, very low quality). However, there was no difference for quality of life (1 study, low quality), length of stay (1 study, moderate quality), or future hospital admissions (1 study, low quality) and a possible increase in mortality at 3 months (1 study, very low quality).

Stratum - Pharmacist at discharge

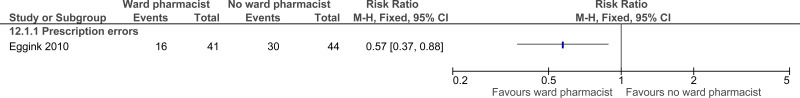

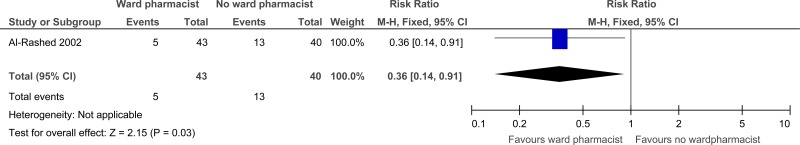

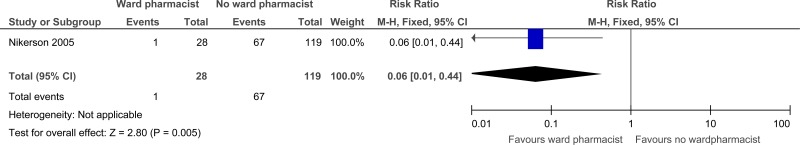

- Four randomised controlled trials comprising 770 people evaluated the role of pharmacists at discharge for improving outcomes in secondary care, in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that pharmacists at discharge may provide a benefit for reduced prescription errors (1 study, low quality), reduced readmissions up to 22 days post discharge (1 study, very low quality) and reducing prescriber errors (drug therapy inconsistencies and omissions) at discharge (1 study, moderate quality). The evidence suggested that pharmacists at discharge have no effect on quality of life scales (1 study, very low to low quality).

Economic

Stratum - Regular ward-based pharmacist support

- Three economic evaluations reported that the ward-based pharmacist intervention was dominant (more effective and less costly) compared to usual care. One of these economic evaluations was a cost-utility analysis reporting a QALY gain of 0.005. These analyses were assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One cost-utility analysis showed that the ward-based pharmacist intervention was cost-effective with an ICER of £632 per QALY gained (as calculated by the NGC). The analysis was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

- One economic evaluation showed that regular ward-based pharmacist support was less effective and less costly, with no clear conclusion regarding cost effectiveness given the absence of a cost-effectiveness threshold for the reported outcomes. The analysis was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

Stratum – pharmacist at admission

- One comparative cost analysis showed that pharmacist support at admission was cost saving compared to usual care. The analysis was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

Stratum – pharmacist at discharge

- One cost-utility analysis showed that the ward-based pharmacist support at discharge was not cost effective, with an ICER of £327,378 per adjusted QALY gained. The analysis was assessed as partially applicable with minor limitations.

30.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendation | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Mortality, avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, length of stay in hospital, prescribing errors, missed medications, and medicines reconciliation were considered by the guideline committee to be critical outcomes. Readmissions, admissions to hospital, discharge from hospital and staff satisfaction were considered by the committee to be important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between clinical benefits and harms |

A total of 18 studies (20 papers) were identified that assessed ward based pharmacist support. They were split into three categories: Regular in-hospital ward based pharmacy support compared to no ward-based pharmacist Eight randomised controlled trials were identified. The evidence suggested that regular in-hospital pharmacist support may provide benefit for reduced mortality, reduced preventable adverse drug events in hospital and at 90 days, length of stay and increased patient and/or carer satisfaction. However, there was no effect on readmission, adverse drug events at 3 to 6 months post discharge and admission. Evidence for the outcome prescribing errors at discharge suggested no difference between the groups for the outcome of reducing prescribing errors at discharge; however there were increased prescribing errors at 30 days in regular in-hospital pharmacist support group compared to no pharmacist support group. No evidence was found for quality of life, missed medications, medicines reconciliation, admissions to hospital, discharges or staff satisfaction. Pharmacist at admission compared to no ward-based pharmacist Six randomised controlled trials were identified. The evidence suggested that pharmacists at admission may provide benefit by reduced medicine errors, total medication errors within 24 hours of admission and physicians agreement. However, there was no difference for quality of life, length of stay, or future hospital admissions and a possible increase in mortality at 3 months. However, the mortality outcome was graded very low quality and the committee interpreted this with caution as it was from 1 small study with low events and wide confidence intervals. No evidence was found for avoidable adverse events, patient and/or carer satisfaction, readmissions, prescribing errors, missed medications or discharges. Pharmacist at discharge compared to no ward-based pharmacist Four randomised controlled trials were identified. The evidence suggested that pharmacists at discharge may provide benefit for reduced prescription errors, reduced readmissions up to 22 days post discharge and prescriber errors (drug therapy inconsistencies and omissions) at discharge. The evidence suggested that pharmacists at discharge have no effect on quality of life scales. No evidence was found for mortality, patient or staff satisfaction, length of stay, future hospital admissions, missed medications, avoidable adverse events or discharges. Summary Overall the evidence demonstrated some potential benefits for ward-based pharmacists supplementing the prescribing and drug delivery activities provided by physicians and nurses. The mechanism by which pharmacists might improve patient outcomes would most likely be through minimising prescribing errors and drug interactions, by ensuring appropriate prescribing or discontinuation of drugs. Pharmacist education and support is likely to improve patient and/or carer satisfaction. Evidence was found for these outcomes, though not in all populations and with some inconsistencies. No evidence was found relating to 7 day provision of a ward pharmacist. The committee decided to make a strong recommendation for ward based pharmacists because there was evidence of benefit in many of the facets of pharmacists’ work even though overall the evidence was relatively weak. The economic evidence was also in favour of the provision of pharmacy support. In addition, the presence of a ward based pharmacist is common practice in the UK and the experience of the committee was positive overall. The committee noted that studies involving the pharmacist at hospital discharge may have reduced the need for junior doctors to explain prescribing regimens, and the need for the patient to visit their general practitioner following discharge for drug review, which may have improved patient and/or carer satisfaction and which would have had a potential cost benefit. The committee also discussed the added value of having a pharmacist as part of daily MDTs (see Chapter 29 on MDTs). Prescription and administration errors are amongst the most commonly identified adverse events during a patient’s stay in hospital. Pharmacists as part of the MDT can reduce these errors and ensure that the patient gets the correct treatment in a time effective manner, as well as discontinuing drugs which are no longer required. The pharmacist has an important educational role which will be likely to improve patients’ compliance after discharge. These activities allow doctors to prioritise other tasks. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

Regular in-hospital pharmacy support compared to no ward-based pharmacist Five economic evaluations were identified.

One UK comparative cost analysis, which showed that the ward-based pharmacist intervention was cost saving compared to usual care. Pharmacist at discharge compared to no ward-based pharmacist One cost-utility analysis showed that the ward-based pharmacist intervention was not cost effective, with an ICER of £327,378 per adjusted QALY gained. There was a suggestion that the lack of seniority of the pharmacists and lack of integration in the ward team reduced the effectiveness in that study. The committee noted that clinical pharmacists in the UK studies were generally experienced (band 7/8) and have specialist knowledge in the medications they managed. This may not be the same profile in all the other non-UK studies. Additionally, standard care/control arm in the included studies was not always clearly defined and was variable in terms of clinical pharmacist input. Some studies included a specified level of clinical pharmacist input in the control group which was enhanced in the intervention group (for example, by attendance at ward rounds) while others described the introduction of a de-novo service. With the exception of the UK modelling study (Karnon 200829); all studies had a follow-up of 12 months or less and hence would not have assessed the long term impact of the ward based pharmacist intervention. Additionally, the majority of the studies assessed a limited number of cost categories; focusing on medication costs, pharmacist time and less on other staff time and patient-related downstream costs. The committee felt there was evidence that pharmacist support throughout the stay would achieve saving in terms of medications costs, which was the most frequently assessed cost category in the included studies. One study found the pharmacist cost was completely offset by medication cost savings. The evidence was less clear in terms of impact on other staff time as well as the impact on long-term patient outcomes, which were not always assessed in the included studies. However, in those studies that assessed impact on other staff time and long-term outcomes, the results showed potential for cost saving that could be extrapolated to the other studies. Avoiding medication errors and litigation costs was raised by the committee as another potential positive outcome. Overall, the committee felt that this could be a cost saving intervention. Overall, the committee concluded that the use of ward-based pharmacists throughout the hospital stay is cost-effective. Pharmacist support only at discharge was shown to be not cost effective but the evidence was limited. |

| Quality of evidence |

The evidence reviewed for in-hospital pharmacist support was of very low to moderate quality due to risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency. The evidence reviewed for pharmacist at admission was of very low to moderate quality due to risk of bias, imprecision and outcome indirectness. The outcome ‘agreement with prescriber’ which was used as a surrogate outcome for staff satisfaction was considered an indirect outcome. The evidence for pharmacist at discharge was of very low to moderate quality due to risk of bias and imprecision. The committee noted the improved benefits shown in the UK studies compared to other countries and felt this was due to the fact that ward-based pharmacists are already well embedded in UK practice. However, the committee did note that these studies did not report the level of pharmacist experience and this may limit the interpretation of benefit. The health economic evidence was assessed to be partially applicable (with only 1 study from the UK and only 1 reporting QALYs). The evidence was also considered to have potentially serious limitations with none of the studies being based on a review of the evidence base and the cost components included being variable. |

| Other considerations |

There was no evidence specifically to support 7 day provision of ward based pharmacists. The committee therefore chose a general recommendation, recognising that pharmacy services would need to be scaled up in parallel with other services in the transition to a 7 day service. Currently medical wards in the UK do have access to a pharmacist. However, the pharmacist may be responsible for covering several areas concurrently; limiting the level of detail they can bring to medicines reconciliation and patient and staff communication. This is particularly important for an ageing population with multiple co-morbidities for whom polypharmacy adds complexity and may indeed be the cause of the acute admission. In this situation the pharmacist plays a vital role advising the medical team regarding the interactions of drugs and how to prescribe treatment optimally. Pharmacists are gradually acquiring independent prescribing rights. This allows them (following consultation with the prescribing doctor) to correct prescribing errors or make changes to better agents, relieving doctors of this task. Prescribing drugs to take home at the end of a person’s hospital stay could also facilitate earlier discharge from hospital and allow junior doctors to focus on other tasks such as the ward rounds. Assessment of the cost-effectiveness of prescribing pharmacists in hospital should include these considerations. |

References

- 1.

- Aag T, Garcia BH, Viktil KK. Should nurses or clinical pharmacists perform medication reconciliation? A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2014; 70(11):1325–1332 [PubMed: 25187339]

- 2.

- Abu-Oliem AS, Al-Sharayri MG, AlJabra RJ, Hakuz NM. A clinical trial to investigate the role of clinical pharmacist in resolving/preventing drug related problems in ICU patients who receive anti-infective therapy. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2013; 6(3):292–298

- 3.

- Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, Sunter W, Chrystyn H. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counselling to elderly patients prior to discharge. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2002; 54(6):657–664 [PMC free article: PMC1874498] [PubMed: 12492615]

- 4.

- Alassaad A, Bertilsson M, Gillespie U, Sundstrom J, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Melhus H. The effects of pharmacist intervention on emergency department visits in patients 80 years and older: subgroup analyses by number of prescribed drugs and appropriate prescribing. PloS One. 2014; 9(11):e111797 [PMC free article: PMC4218816] [PubMed: 25364817]

- 5.

- Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Impact of an enhanced pharmacy discharge service on prescribing appropriateness criteria: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2015; 37(6):1194–1205 [PubMed: 26297239]

- 6.

- Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, Burdick E, Laird N, Petersen LA et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997; 277(4):307–311 [PubMed: 9002493]

- 7.

- Bessesen MT, Ma A, Clegg D, Fugit RV, Pepe A, Goetz MB et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: comparison of a program with infectious diseases pharmacist support to a program with a geographic pharmacist staffing model. Hospital Pharmacy. 2015; 50(6):477–483 [PMC free article: PMC4568108] [PubMed: 26405339]

- 8.

- Bladh L, Ottosson E, Karlsson J, Klintberg L, Wallerstedt SM. Effects of a clinical pharmacist service on health-related quality of life and prescribing of drugs: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011; 20(9):738–746 [PubMed: 21209140]

- 9.

- Bolas H, Brookes K, Scott M, McElnay J. Evaluation of a hospital-based community liaison pharmacy service in Northern Ireland. Pharmacy World and Science. 2004; 26(2):114–120 [PubMed: 15085948]

- 10.

- Burnett KM, Scott MG, Fleming GF, Clark CM, McElnay JC. Effects of an integrated medicines management program on medication appropriateness in hospitalized patients. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2009; 66(9):854–859 [PubMed: 19386949]

- 11.

- Cani CG, Lopes LdSG, Queiroz M, Nery M. Improvement in medication adherence and self-management of diabetes with a clinical pharmacy program: a randomized controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing insulin therapy at a teaching hospital. Clinics. 2015; 70(2):102–106 [PMC free article: PMC4351311] [PubMed: 25789518]

- 12.

- Chen J-H, Ou H-T, Lin T-C, Lai ECC, Yang KYH. Pharmaceutical care of elderly patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2016; 38(1):88–95 [PubMed: 26499503]

- 13.

- Claus BOM, Robays H, Decruyenaere J, Annemans L. Expected net benefit of clinical pharmacy in intensive care medicine: a randomized interventional comparative trial with matched before-and-after groups. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2014; 20(6):1172–1179 [PubMed: 25470782]

- 14.

- de Boer M, Ramrattan MA, Kiewiet JJS, Boeker EB, Gombert-Handoko KB, van Lent-Evers NAEM et al. Cost-effectiveness of ward-based pharmacy care in surgical patients: protocol of the SUREPILL (Surgery & Pharmacy In Liaison) study. BMC Health Services Research. 2011; 11:55 [PMC free article: PMC3059300] [PubMed: 21385352]

- 15.

- Eggink RN, Lenderink AW, Widdershoven JWMG, van den Bemt PMLA. The effect of a clinical pharmacist discharge service on medication discrepancies in patients with heart failure. Pharmacy World and Science. 2010; 32(6):759–766 [PMC free article: PMC2993887] [PubMed: 20809276]

- 16.

- Engelhardt JB, McClive-Reed KP, Toseland RW, Smith TL, Larson DG, Tobin DR. Effects of a program for coordinated care of advanced illness on patients, surrogates, and healthcare costs: a randomized trial. American Journal of Managed Care. 2006; 12(2):93–100 [PubMed: 16464138]

- 17.

- Farley TM, Shelsky C, Powell S, Farris KB, Carter BL. Effect of clinical pharmacist intervention on medication discrepancies following hospital discharge. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2014; 36(2):430–437 [PMC free article: PMC4026363] [PubMed: 24515550]

- 18.

- Farris KB, Carter BL, Xu Y, Dawson JD, Shelsky C, Weetman DB et al. Effect of a care transition intervention by pharmacists: an RCT. BMC Health Services Research. 2014; 14:406 [PMC free article: PMC4262237] [PubMed: 25234932]

- 19.

- Fertleman M, Barnett N, Patel T. Improving medication management for patients: the effect of a pharmacist on post-admission ward rounds. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2005; 14(3):207–211 [PMC free article: PMC1744029] [PubMed: 15933319]

- 20.

- Ghatnekar O, Bondesson A, Persson U, Eriksson T. Health economic evaluation of the Lund Integrated Medicines Management Model (LIMM) in elderly patients admitted to hospital. BMJ Open. Sweden 2013; 3(1):e001563 [PMC free article: PMC3553390] [PubMed: 23315436]

- 21.

- Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009; 169(9):894–900 [PubMed: 19433702]

- 22.

- Graabaek T, Kjeldsen LJ. Medication reviews by clinical pharmacists at hospitals lead to improved patient outcomes: a systematic review. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2013; 112(6):359–373 [PubMed: 23506448]

- 23.

- Heselmans A, van Krieken J, Cootjans S, Nagels K, Filliers D, Dillen K et al. Medication review by a clinical pharmacist at the transfer point from ICU to ward: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2015; 40(5):578–583 [PubMed: 29188903]

- 24.

- Hodgkinson B, Koch S, Nay R, Nichols K. Strategies to reduce medication errors with reference to older adults. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2006; 4(1):2–41 [PubMed: 21631752]

- 25.

- Horn E, Jacobi J. The critical care clinical pharmacist: evolution of an essential team member. Critical Care Medicine. 2006; 34:(Suppl 3):S46–S51 [PubMed: 16477202]

- 26.

- Israel EN, Farley TM, Farris KB, Carter BL. Underutilization of cardiovascular medications: effect of a continuity-of-care program. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2013; 70(18):1592–1600 [PMC free article: PMC4019344] [PubMed: 23988600]

- 27.

- Jarab AS, Alqudah SG, Khdour M, Shamssain M, Mukattash TL. Impact of pharmaceutical care on health outcomes in patients with COPD. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2012; 34(1):53–62 [PubMed: 22101426]

- 28.

- Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006; 166(9):955–964 [PubMed: 16682568]

- 29.

- Karnon J, McIntosh A, Dean J, Bath P, Hutchinson A, Oakley J et al. Modelling the expected net benefits of interventions to reduce the burden of medication errors. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. United Kingdom 2008; 13(2):85–91 [PubMed: 18416913]

- 30.

- Karnon J, McIntosh A, Bath P, Hutchinson A, Oakley J, Freeman-Parry L et al. A prospective hazard and improvement analysis of medication errors in a UK secondary care setting, 2007. Available from: http://www

.birmingham .ac.uk/Documents/college-mds /haps/projects /cfhep/psrp/finalreports /PS018FinalReportKarnon.pdf - 31.

- Khalil V, deClifford JM, Lam S, Subramaniam A. Implementation and evaluation of a collaborative clinical pharmacist’s medications reconciliation and charting service for admitted medical inpatients in a metropolitan hospital. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2016; 41(6):662–666 [PubMed: 27578624]

- 32.

- Klopotowska JE, Kuiper R, vanKan HJ, dePont AC, Dijkgraaf MG, Lie AH et al. On-ward participation of a hospital pharmacist in a Dutch intensive care unit reduces prescribing errors and related patient harm: an intervention study. Critical Care. Netherlands 2010; 14(5):R174 [PMC free article: PMC3219276] [PubMed: 20920322]

- 33.

- Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D et al. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2009; 4(4):211–218 [PubMed: 19388074]

- 34.

- Kucukarslan SN, Corpus K, Mehta N, Mlynarek M, Peters M, Stagner L et al. Evaluation of a dedicated pharmacist staffing model in the medical intensive care unit. Hospital Pharmacy. 2013; 48(11):922–930 [PMC free article: PMC3875111] [PubMed: 24474833]

- 35.

- Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003; 163(17):2014–2018 [PubMed: 14504113]

- 36.

- Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, Burdick E, Demonaco HJ, Erickson JI et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999; 282(3):267–270 [PubMed: 10422996]

- 37.

- Lind KB, Soerensen CA, Salamon SA, Jensen TM, Kirkegaard H, Lisby M. Impact of clinical pharmacist intervention on length of stay in an acute admission unit: a cluster randomised study. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2016; 23(3):171–176 [PMC free article: PMC6451522] [PubMed: 31156841]

- 38.

- Lipton HL, Bero LA, Bird JA, McPhee SJ. The impact of clinical pharmacists’ consultations on physicians’ geriatric drug prescribing. A randomized controlled trial. Medical Care. 1992; 30(7):646–658 [PubMed: 1614233]

- 39.

- Lisby M, Thomsen A, Nielsen LP, Lyhne NM, Breum-Leer C, Fredberg U et al. The effect of systematic medication review in elderly patients admitted to an acute ward of internal medicine. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2010; 106(5):422–427 [PubMed: 20059474]

- 40.

- MacLaren R, Bond CA. Effects of pharmacist participation in intensive care units on clinical and economic outcomes of critically ill patients with thromboembolic or infarction-related events. Pharmacotherapy. United States 2009; 29(7):761–768 [PubMed: 19558249]

- 41.

- Makowsky MJ, Koshman SL, Midodzi WK, Tsuyuki RT. Capturing outcomes of clinical activities performed by a rounding pharmacist practicing in a team environment: the COLLABORATE study [NCT00351676]. Medical Care. 2009; 47(6):642–650 [PubMed: 19433997]

- 42.

- Malone DC, Carter BL, Billups SJ, Valuck RJ, Barnette DJ, Sintek CD et al. Can clinical pharmacists affect SF-36 scores in veterans at high risk for medication-related problems? Medical Care. 2001; 39(2):113–122 [PubMed: 11176549]

- 43.

- Mousavi M, Hayatshahi A, Sarayani A, Hadjibabaie M, Javadi M, Torkamandi H et al. Impact of clinical pharmacist-based parenteral nutrition service for bone marrow transplantation patients: a randomized clinical trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013; 21(12):3441–3448 [PubMed: 23949839]

- 44.

- Nester TM, Hale LS. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-acquired medication history in promoting patient safety. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2002; 59(22):2221–2225 [PubMed: 12455306]

- 45.

- Neto PRO, Marusic S, de Lyra Junior DP, Pilger D, Cruciol-Souza JM, Gaeti WP et al. Effect of a 36-month pharmaceutical care program on the coronary heart disease risk in elderly diabetic and hypertensive patients. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011; 14(2):249–263 [PubMed: 21733413]

- 46.

- Nickerson A, MacKinnon NJ, Roberts N, Saulnier L. Drug-therapy problems, inconsistencies and omissions identified during a medication reconciliation and seamless care service. Healthcare Quarterly. 2005; 8 Spec No:65–72 [PubMed: 16334075]

- 47.

- O’Dell KM, Kucukarslan SN. Impact of the clinical pharmacist on readmission in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2005; 39(9):1423–1427 [PubMed: 16046491]

- 48.

- O’Sullivan D, O’Mahony D, O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, Gallagher J, Cullinan S et al. Prevention of adverse drug reactions in hospitalised older patients using a software-supported structured pharmacist intervention: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Drugs and Aging. 2016; 33(1):63–73 [PubMed: 26597401]

- 49.

- Okumura LM, Rotta I, Correr CJ. Assessment of pharmacist-led patient counseling in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2014; 36(5):882–891 [PubMed: 25052621]

- 50.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Purchasing power parities (PPP), 2007. Available from: http://www

.oecd.org/std/ppp - 51.

- Penm J, Li Y, Zhai S, Hu Y, Chaar B, Moles R. The impact of clinical pharmacy services in China on the quality use of medicines: a systematic review in context of China’s current healthcare reform. Health Policy and Planning. 2014; 29(7):849–872 [PubMed: 24056897]

- 52.

- Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, Hansen LO, Williams MV, Vetter E et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (IPITCH Study). Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2016; 11(1):39–44 [PubMed: 26434752]

- 53.

- Renaudin P, Boyer L, Esteve M-A, Bertault-Peres P, Auquier P, Honore S. Do pharmacist-led medication reviews in hospitals help reduce hospital readmissions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2016; 82(6):1660–1673 [PMC free article: PMC5099542] [PubMed: 27511835]

- 54.

- Roblek T, Deticek A, Leskovar B, Suskovic S, Horvat M, Belic A et al. Clinical-pharmacist intervention reduces clinically relevant drug-drug interactions in patients with heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016; 203:647–652 [PubMed: 26580349]

- 55.

- Sadik A, Yousif M, McElnay JC. Pharmaceutical care of patients with heart failure. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005; 60(2):183–193 [PMC free article: PMC1884928] [PubMed: 16042672]

- 56.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, Wahlstrom SA, Brown BA, Tarvin E et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006; 166(5):565–571 [PubMed: 16534045]

- 57.

- Scullin C, Scott MG, Hogg A, McElnay JC. An innovative approach to integrated medicines management. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007; 13(5):781–788 [PubMed: 17824872]

- 58.

- Shen J, Sun Q, Zhou X, Wei Y, Qi Y, Zhu J et al. Pharmacist interventions on antibiotic use in inpatients with respiratory tract infections in a Chinese hospital. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2011; 33(6):929–933 [PubMed: 22068326]

- 59.

- Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S, Lambert P, Nachega JB, Wilmotte L et al. Effect of a collaborative approach on the quality of prescribing for geriatric inpatients: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007; 55(5):658–665 [PubMed: 17493184]

- 60.

- Stowasser DA, Collins DM, Stowasser M. A randomised controlled trial of medication liaison services - patient outcomes. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2002; 32(2):133–140

- 61.

- Suhaj A, Manu MK, Unnikrishnan MK, Vijayanarayana K, Mallikarjuna Rao C. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacist intervention on health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder patients - a randomized controlled study. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2016; 41(1):78–83 [PubMed: 26775599]

- 62.

- Tong EY, Roman C, Mitra B, Yip G, Gibbs H, Newnham H et al. Partnered pharmacist charting on admission in the General Medical and Emergency Short-stay Unit - a cluster-randomised controlled trial in patients with complex medication regimens. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2016; 41(4):414–418 [PubMed: 27255463]

- 63.

- Upadhyay DK, Ibrahim MI, Mishra P, Alurkar VM, Ansari M. Does pharmacist-supervised intervention through pharmaceutical care program influence direct healthcare cost burden of newly diagnosed diabetics in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal: a non-clinical randomised controlled trial approach. Daru. 2016; 24(1):6 [PMC free article: PMC4772684] [PubMed: 26926657]

- 64.

- Upadhyay DK, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Mishra P, Alurkar VM. A non-clinical randomised controlled trial to assess the impact of pharmaceutical care intervention on satisfaction level of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. BMC Health Services Research. 2015; 15:57 [PMC free article: PMC4448530] [PubMed: 25888828]

- 65.

- Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, Blalock SJ, Coker-Schwimmer E, Posey R et al. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015; 175(1):76–87 [PubMed: 25401788]

- 66.

- Wallerstedt SM, Bladh L, Ramsberg J. A cost-effectiveness analysis of an in-hospital clinical pharmacist service. BMJ Open. Sweden 2012; 2(1):e00032 [PMC free article: PMC3253415] [PubMed: 22223840]

- 67.

- Wang Y, Wu H, Xu F. Impact of clinical pharmacy services on KAP and QOL in cancer patients: a single-center experience. BioMed Research International. 2015; 2015:502431 [PMC free article: PMC4677164] [PubMed: 26697487]

- 68.

- Zhao S, Zhao H, Du S, Qin Y. Impact of pharmaceutical care on the prognosis of patients with coronary heart disease receiving multidrug therapy. Pharmaceutical Care and Research. 2015; 15(3):179–181

- 69.

- Zhao S, Zhao H, Du S, Qin Y. The impact of clinical pharmacist support on patients receiving multi-drug therapy for coronary heart disease in china: a long-term follow-up study. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2015; 22(6):323–327 [PMC free article: PMC4502145] [PubMed: 26180276]

- 70.

- Zhao SJ, Zhao HW, Du S, Qin YH. The impact of clinical pharmacist support on patients receiving multi-drug therapy for coronary heart disease in China. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015; 77(3):306–311 [PMC free article: PMC4502145] [PubMed: 26180276]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Table 11Review protocol: Pharmacist support

| Review question | Do ward-based pharmacists improve outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed acute medical emergency? |

|---|---|

| Guideline condition and its definition | Acute medical emergencies. Definition: People with suspected or confirmed acute medical emergencies or at risk of an acute medical emergency |

| Review population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed AME |

| Adults and young people (16 years and over) | |

| Line of therapy not an inclusion criterion | |

|

Interventions and comparators: generic/class; specific/drug (All interventions will be compared with each other, unless otherwise stated) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Unit of randomisation |

Patient Hospital Ward |

| Crossover study | Not permitted |

| Minimum duration of study | Not defined |

| Subgroup analyses if there is heterogeneity |

|

| Search criteria |

Databases: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library Date limits for search: No date limits Language: English |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

C.1. Regular in-hospital pharmacist support

C.2. Pharmacist at admission

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (781K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

E.1. Regular ward-based pharmacist support

Download PDF (573K)

E.2. Pharmacist at admission

Download PDF (425K)

E.3. Pharmacist at discharge

Download PDF (441K)

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 12Clinical evidence profile: Regular in-hospital pharmacy support versus no ward-based pharmacist

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Regular in-hospital pharmacist support | No ward-based pharmacist | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (follow-up median 1 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

105/534 (19.7%) | 19.8% | RR 0.92 (0.72 to 1.16) | 16 fewer per 1000 (from 55 fewer to 32 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Survival (follow-up 1 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

0/182 (0%) | 0% | HR 0.94 (0.65 to 1.36) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Admissions to hospital (over 30 days) (follow-up median 1 years) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

327/942 (34.7%) | 38.4% | RR 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) | 27 fewer per 1000 (from 65 fewer to 15 more) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| Readmission (follow-up 30 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

40/298 (13.4%) | 14.6% | RR 0.92 (0.62 to 1.37) | 12 fewer per 1000 (from 55 fewer to 54 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Prescribing errors (follow-up at discharge; measured with: medication appropriateness index; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious inconsistency3 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 408 | 403 | - | MD 0.02 lower (0.12 lower to 1.08 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Prescribing errors (follow-up 30 days; measured with: medication appropriateness index; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 304 | 309 | - | MD 2.1 higher (0.45 to 3.75 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Preventable adverse drug events (follow-up until discharge) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | very serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

5/391 (1.3%) | 5.4% | RR 0.74 (0.06 to 8.57) | 14 fewer per 1000 (from 51 fewer to 409 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

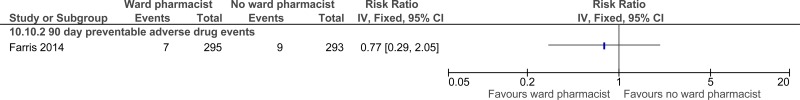

| Preventable adverse drug events (follow-up 90 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

7/295 (2.4%) | 3.1% | RR 0.77 (0.29 to 2.05) | 7 fewer per 1000 (from 22 fewer to 33 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

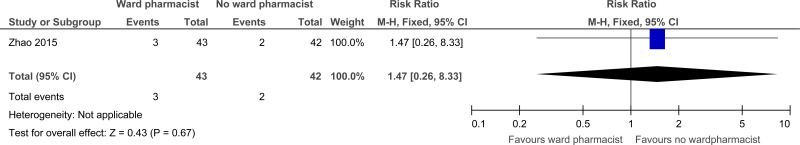

| Adverse drug reactions (follow-up 6 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

3/43 (7%) | 4.8% | RR 1.47 (0.26 to 8.33) | 23 more per 1000 (from 36 fewer to 352 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

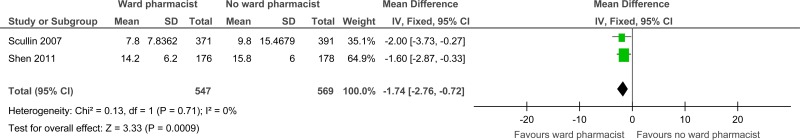

| Length of stay (days) (follow-up in-hospital; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 547 | 569 | - | MD 1.74 lower (2.76 to 0.72 lower) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

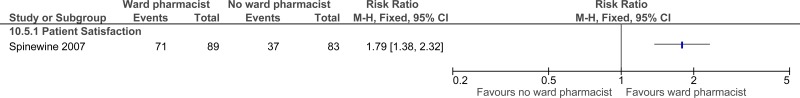

| Patient and/or carer satisfaction (follow-up 1 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

71/89 (79.8%) | 44.6% | RR 1.79 (1.38 to 2.32) | 352 more per 1000 (from 169 more to 589 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Patient and/or carer satisfaction (at discharge) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

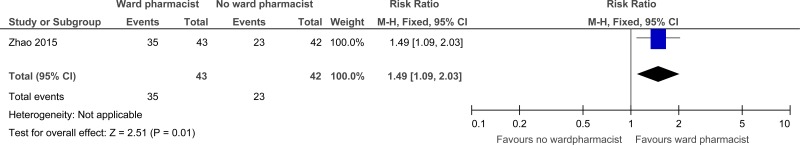

35/43 (81.4%) | 54.8% | RR 1.49 (1.09 to 2.03) | 269 more per 1000 (from 49 more to 564 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 because: The point estimate varies widely across studies

Table 13Clinical evidence profile: Pharmacist at admission versus no ward-based pharmacist

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Pharmacist at admission | No ward-based pharmacist | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Medication reconciliation (measured with: errors identified at admission; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

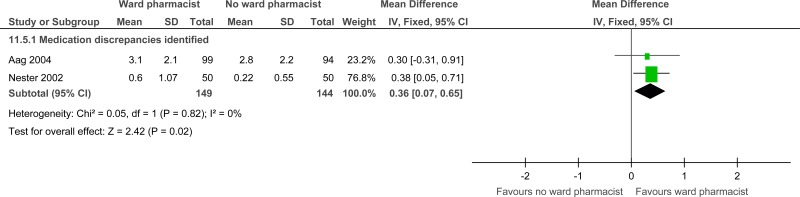

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none | 149 | 144 | - | MD 0.36 higher (0.07 to 0.65 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (follow-up 3 months; measured with: EQ-VAS index; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

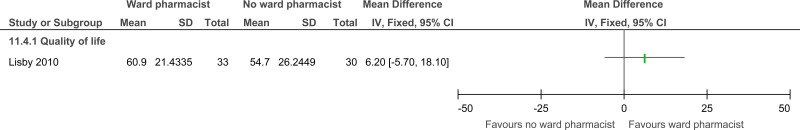

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none | 33 | 30 | - | MD 6.2 higher (5.7 lower to 18.1 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Length of stay (follow-up in-hospital; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

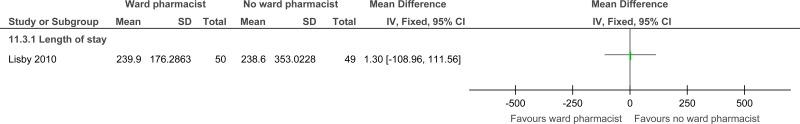

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 50 | 49 | - | MD 1.3 higher (108.96 lower to 111.56 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Admission (follow-up 3 months; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

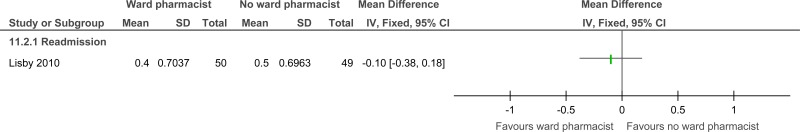

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none | 50 | 49 | - | MD 0.1 lower (0.38 lower to 0.18 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

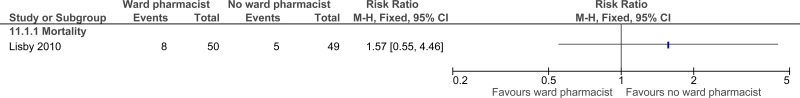

| Mortality (follow-up 3 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious2 | none |

8/50 (16%) | 10.2% | RR 1.57 (0.55 to 4.46) | 58 more per 1000 (from 46 fewer to 353 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

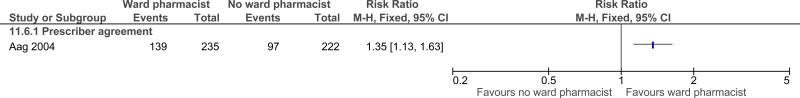

| Staff satisfaction (follow-up at admission; assessed with: Physician agreement) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious3 | serious2 | none |

139/235 (59.1%) | 43.7% | RR 1.35 (1.13 to 1.63) | 153 more per 1000 (from 57 more to 275 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

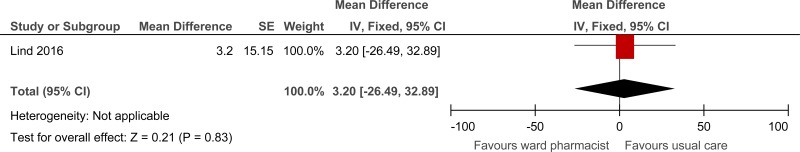

| Length of stay in AAU (minutes) (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 216 | 232 | - | 3.2 higher (26.49 lower to 32.89 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

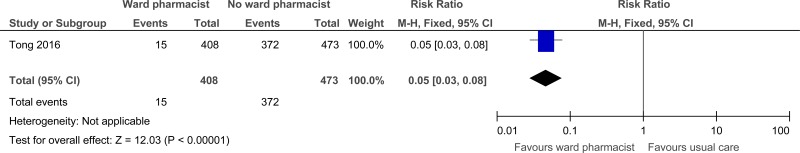

| Total medication errors within 24 hours of admission (Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

15/408 (3.7%) | 0% | RR 0.05 (0.03 to 0.08) | 748 fewer per 1000 (from 772 fewer to 763 fewer) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

- 3

The majority of the evidence had indirect outcomes.

Table 14Clinical evidence profile: Pharmacist at discharge versus no ward-based pharmacist

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Pharmacist at discharge | No ward-based pharmacist | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Prescription errors (follow-up 6 weeks; assessed with: identification at outpatient follow-up) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

16/41 (39%) | 68.2% | RR 0.57 (0.37 to 0.88) | 293 fewer per 1000 (from 82 fewer to 430 fewer) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

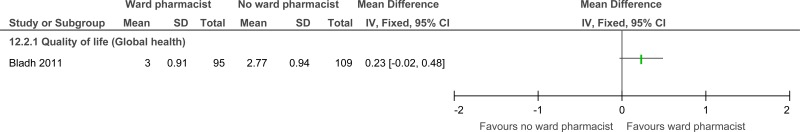

| Quality of life (follow-up 6 months; measured with: Global health index; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none | 95 | 109 | - | MD 0.23 higher (0.02 lower to 0.48 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

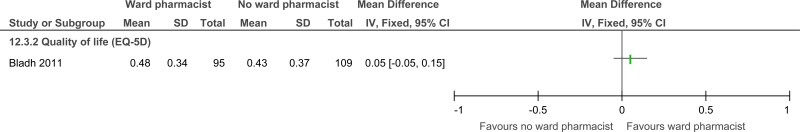

| Quality of life (follow-up 6 months; measured with: Summated EQ-5D index; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 95 | 109 | - | MD 0.05 higher (0.05 lower to 0.15 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

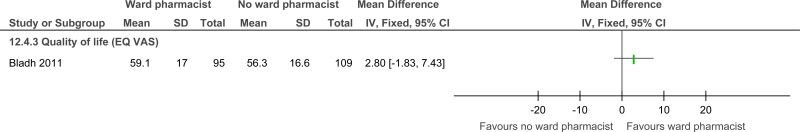

| Quality of life (follow-up 6 months; measured with: EQ-VAS index; range of scores: 0-100; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | 95 | 109 | - | MD 2.8 higher (1.83 lower to 7.43 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Readmission (follow-up 15-22 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | none |

5/43 (11.6%) | 32.5% | RR 0.36 (0.14 to 0.91) | 208 fewer per 1000 (from 29 fewer to 279 fewer) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Prescriber errors (Drug therapy inconsistencies and omissions) (follow-up at discharge) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none |

1/28 (3.6%) | 56.3% | RR 0.06 (0.01 to 0.44) | 529 fewer per 1000 (from 315 fewer to 557 fewer) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 15Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Abu-oliem 20132 | Inappropriate comparison (ward-based pharmacist) |

| Alassaad 20144 | Incorrect comparison. Post-hoc subgroup analysis for no of prescribed drugs from included study (Gillespie 200921) |

| Basger 20155 | Incorrect population (patients admitted for treatment of chronic disease in addition to rehab after joint replacement surgery) |

| Bessen 20157 | Inappropriate study design (comparison of 2 hospitals) |

| Bolas 20049 | No extractable outcomes |

| Burnett 200910 | Inappropriate comparison (normal care involved chart reviews, counselling etc. by pharmacists) |

| Cani 201511 | Not review population (chronic disease management) |

| Chen 201612 | Incorrect population (patients with chronic condition, not admitted to hospital); incorrect intervention (pharmacists were not ward-based) |

| De boer 201114 | Protocol only |

| Ghatnekar 2013A20 | Inappropriate study design (health economic model); no relevant outcomes |

| Graabaek 201322 | Systematic review: study designs inappropriate (non-randomised studies, non-ward based interventions, ward-based comparators) |

| Heselmans 201523 | Incorrect intervention (drug therapy changes communicated to the physician; pharmacist was not ward-based) |

| Hodgkinson 200624 | Systematic review: study designs inappropriate (non-randomised studies, non-ward based interventions, ward-based comparators) |

| Horn 200625 | No intervention (literature review) |

| Israel 201326 | No relevant outcomes (underutilization of cardiovascular medications) |

| Jarab 201227 | Study to be considered in the comm pharm review |

| Kaboli 200628 | Systematic review: study designs inappropriate (non-randomised studies, non-ward based interventions, ward-based comparators) |

| Koehler 2009A33 | Inappropriate comparison- care bundle including clinical pharmacist for elderly high risk patients compared to usual care group including staff pharmacist |

| Klopotowska 201032 | Incorrect study design (before and after) |

| Kucukarslan 201334 | Incorrect study design (before and after) |

| Leape 199936 | Incorrect study design (observational) |

| Lipton 199238 | Incorrect interventions (post-discharge care) |

| Maclaren 200940 | Incorrect study design (retrospective cohort) |

| Makowsky 200941 | Inappropriate comparison (ward-based pharmacist) |

| Malone 200142 | Not review population (ambulatory care) |

| Mousavi 201343 | Not review population (nutritional support service) |

| Neto 201145 | Incorrect interventions (not ward-based) |

| O’dell 200547 | Incorrect study design (non-randomised, observational) |

| Okumura 201449 | Systematic review has unclear PICO (no breakdown of studies, most took place in ambulatory care) |

| O’Sullivan 201648 | Inappropriate comparison (pharmacist review vs. clinical decision support software supported pharmacist review) |

| Penm 201451 | Systematic review (studies based in China only; references screened) |

| Phatak 201652 | Inappropriate comparison (normal care involved daily pharmacist assessment) |

| Renaudin 201653 | Systematic review and meta-analysis- ordered relevant references |

| Roblek 201654 | Incorrect intervention (advice about drug-drug interactions given to physicians; pharmacist was not ward-based) |

| Sadik 200555 | Study to be considered in the comm pharm review |

| Schnipper 200656 | Study to be considered in the comm pharm review |

| Stowasser 200260 | Incorrect interventions (not ward-based) |

| Suhaj 201661 | Incorrect population (patients with chronic condition, not admitted to hospital); incorrect intervention (pharmacists were not ward-based) |

| Upadhyay 201564 | Incorrect population (patients with chronic condition, not admitted to hospital); incorrect intervention (pharmacists were not ward-based) |

| Upadhyay 201663 | Incorrect population (patients with chronic condition, not admitted to hospital); incorrect intervention (pharmacists were not ward-based); no relevant outcomes |

| Viswanathan 201565 | Systematic review is not relevant (outpatient settings only) |

| Wang 2015A67 | Incorrect population (patients with cancer, not admitted to hospital); incorrect intervention (pharmacists were not ward-based) |

| Zhao 2015E68 | Article not in English |

Appendix H. Excluded economic studies

No studies were excluded.

Footnotes

- (a)

NICE’s guideline on medicines optimisation includes recommendations on medicines-related communication systems when patients move from one care setting to another, medicines reconciliation, clinical decision support, and medicines-related models of organisational and cross-sector working.

Tables

Table 1PICO characteristics of review question

| Population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed AME |

|---|---|

| Interventions |

|

| Comparison | No ward based pharmacists |

| Outcomes |

Mortality (CRITICAL) Quality of life (CRITICAL) Patient and/or carer satisfaction (CRITICAL) Avoidable adverse events (CRITICAL) Length of stay in hospital (CRITICAL) Prescribing errors (CRITICAL) Missed medications (CRITICAL) Medicines reconciliation (CRITICAL) Readmissions up to 30 days (IMPORTANT) Future admissions to hospital (over 30 days) (IMPORTANT) Discharges (IMPORTANT) Staff satisfaction (IMPORTANT) |

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

Table 2Summary of studies included in the review (regular in-hospital pharmacy support)

| Study | Intervention and comparison | Population | Outcomes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Claus 201413 RCT | Pharmacist present on the ward. Duties included making active recommendations and performing patient follow-up. |

Surgical ICU admissions (n=69) within a university hospital in Belgium. Inclusion - over 16 years of age, length of stay greater than 48 hours. Exclusion - none stated. | In-hospital mortality. |

No pharmacist screening or discharge services. Patients crossed to intervention group if the pharmacist was asked by the caregiver to give advice. Pharmacist saw all patients, but recommendations were not passed onto the caregiver in the control group. Intervention conducted by 1 of 2 clinical pharmacists. |

|

Iowa Continuity of Care Study trial: Farris 201418 (Farley 201417) RCT |

Pharmacy case manager. Duties included medication reconciliation, ward visits and discharge service. Versus Nurse based medication reconciliation and discharge service. |

General medicine, family medicine, cardiology or orthopaedic admissions (n=631) within an academic tertiary care hospital in the USA. Inclusion - patients with certain disease classifications: hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or receiving oral anticoagulation. |

Preventable adverse drug events in-hospital; post-discharge (90 days) hospital Readmission at 30 days; Admission at 90 days Medication appropriatene ss index (MAI) at discharge; 30 days; 90 days. |

Farley 2010 indicates that the initial medication reconciliation is normally undertaken by a nurse in the control group. Unclear number of pharmacists involved. Data was extracted from Farris 2014 MAI is based on 6 criteria. |

|

Gillespie 200921 RCT |

Pharmacist present on the ward. Duties included taking part in the rounding team, documenting medication history, and discharge counselling. Versus No pharmacist involvement in the healthcare team at the ward level. |

Patients (n=400) admitted to the 2 acute internal study wards at a University teaching hospital in Sweden. Inclusion - 80 years of age. Exclusion - previously been admitted to the study wards during the study period or had scheduled admissions. |

Overall survival at 12 months, reported as hazard ratio. Admission at 12 months |

A follow-up telephone call to patients 2 months after discharge was conducted in the intervention group Admission and discharge documentation filled by physicians and nurses in comparison group Intervention conducted by 1 of 3 clinical pharmacists. During follow-up period intervention patients received enhanced care again, but were excluded if admitted during the intervention period. |

|

Kucukarslan 200335 Quasi-RCT |

Pharmacist present on the ward. Duties included taking part in the rounding team, documenting medication history, and discharge counselling. Versus Standard care from 1 pharmacist (implication in paper that this is not ward-based). |

All patients (n=165) admitted to 1 of the 2 internal medicine study wards within a tertiary care hospital in the USA. Inclusion - admitted to the internal medicine service and remained in the same patient care unit until discharge. Exclusion – none given. |

Avoidable adverse drug events until discharge. Length of stay in-hospital (reported as mean difference). Re-admission (unclear follow-up time, reported as percentage reduction). |

Admitting process was based on the availability of beds and physician service. Pharmacist on the ward Mon-Fri. Intervention conducted by 1 of 2 clinical pharmacists. Usual care involved identification of medication problems retrospectively through records |

|

Shen 201158 China RCT |

Clinical pharmacist part of the treating team – communicated any potentially inappropriate antibiotic use (indication, choice, dosage, dosing schedule, duration, conversion) with the physician to discuss and make recommendations. Versus. Standard treatment strategies performed by the physicians and nurses without pharmacist involvement. |

n=354 inpatients in 2 respiratory wards diagnosed with respiratory tract infections. Exclusion criteria: transferred from other medical departments; transferred to other medical departments for further treatment; already received antibiotics before admission; did not receive antibiotics during hospitalisation. | Length of stay. | Regular-in ward pharmacist support strata. |

|

Scullin 200757 RCT |

Pharmacist present on the ward. Duties included admission services, in-patient monitoring, and discharge services Versus Traditional clinical pharmacy services (no further details given). |

Admitted patients (n=762) to the 4 medical study wards within 3 general hospitals in northern Ireland. One of the following criteria: taking at least 4 regular medication, were taking a high risk drug(s), were taking antidepressants and were 65 years old or older, had a hospital admission within the last 6 months, prescribed antibiotics on day 1 of admission. Exclusion - scheduled admissions and patients admitted from private nursing homes. |

Admission at 12 months. Mortality at 12 months. Length of stay. | Intervention conducted by 1 of 4 clinical pharmacists/pharm acy technician pairs. |

|

Spinewine 200759 RCT |

Pharmacist present on the ward. Duties included taking part in the rounding team, documenting medication history, and discharge counselling. Versus Usual care (no details of any clinical pharmacist involvement). |

All eligible patients (n=186) admitted to the Geriatric Evaluation and Management (GEM) unit within a university teaching hospital in Belgium. GEM unit accepted patients over 70 years of age. |

Rate of death at 1 year follow-up. Satisfaction with information received. Admission at 12 months. Medical appropriateness index. |

Pharmacist was on the unit for 4 days a week. Intervention conducted by a single clinical pharmacist. GEM team consisted of 2 geriatricians, 2 residents, nurses, 2 physiotherapists, a social worker, a psychologist, and an occupational therapist. MAI is based on 10 criteria (not defined). |

|

RCT |

Interventions by clinical pharmacists including individual drug regimens, attending daily medical rounds, advice to physicians, education of medical staff, patient education on lifestyle changes, psychological interventions such as stress reduction, medication counselling at discharge, monthly follow up telephone calls post-discharge. Versus Conventional medical treatment without pharmacist participation. |

n=90 patients admitted to the cardiology ward in a hospital in China. Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of CHD by physician, accepted ≥4 kinds of drugs, ≥18 years, primary high school education, able to complete the study, available for telephone follow up. Exclusion criteria: pregnant/lactating women, patients enrolled in other studies, severe co-morbidities, family history of psychosis, and barriers to communication. |

Avoidable adverse events (adverse drug reactions). Patient and/or carer satisfaction. |

Table 3Summary of studies included in the review (pharmacist at admission)

| Study | Intervention and comparison | Population | Outcomes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aag 20141 RCT |

Pharmacist medication reconciliation. Versus Nurse medication reconciliation. |

Consecutively admitted patients (n=201) to the Cardiology study ward at a University hospital in Norway. Inclusion - aged 18 and over. Exclusion - terminal illness, isolated due to an infectious disease, unable to communicate in either Norwegian or English. |

Medication discrepancies identified at admission. Prescribing physician agreement at admission. |

Agreement with prescriber used as a surrogate outcome for staff satisfaction. Both pharmacists and nurses were taught and trained by an independent, experience clinical pharmacist both theoretically and practically in order to perform medicine reconciliation. Study involved 3 pharmacists and 3 nurses. |

|

Khalil 201631 Australia RCT |

Pharmacist-initiated medication reconciliation – pharmacist obtained a ‘best possible medication history’ from the patient and/or other sources, undertook admission medication reconciliation, reviewed current medications and the need for new medications in relation to the admission diagnosis, developed a medication management plan with the referring senior medical officer and charted on the electronic medication administration record Versus Usual care – medication orders charted by medical staff. |

n=110 adult medical patients admitted to the acute assessment and admission (AAA) unit via the ED during pharmacy operating hours (8.30am – 5pm). Exclusion criteria: not admitted to the AAA ward within 24 hours; no medications prior to admission; not a general medical patient. | Prescribing errors. | Pharmacist at admission strata. |

|

Lind 201637 Denmark RCT |

Clinical pharmacist intervention - obtaining medication history (using a minimum of 2 sources, 1 of which was an interview with the patient and/or relatives where possible), entering prescriptions into the electronic medication module (EMM), medication reconciliation, reviewing overall medication treatment and writing a note in the electronic medical record. Versus Standard care – on arrival, patients triaged by a nurse, then seen by a physician who was responsible for obtaining medication history, reconciling and assessing medication treatment and entering prescriptions in the EMM. |

n=448 patients arriving at the acute admission unit on weekdays 9am-4.15pm. Inclusion criteria: ≥18 years, taking ≥4 drugs daily (including over-the-counter, herbals and supplements). Exclusion criteria: terminal or intoxicated; assigned to triage level 1; referred to acute outpatient clinic; unable to give informed consent; interviewed by physician prior to giving informed consent; unexpected overnight stay. | Length of stay on the acute admission unit (defined as interval in minutes between arrival and discharge or transfer to a hospital ward). | Pharmacist at admission strata. |

|

Lisby 201039 RCT |

Pharmacist admission review. Versus Senior physician admission review. |

Consecutively admitted patients (n=100) to acute internal medicine study ward within 1 regional hospital in Denmark. Inclusion - patients were 70 years or older. |

Self-experienced quality of health at 3 months. Length of stay in hospital. Admission rate at 3 months. Mortality. | Unclear number of pharmacists involved. |

|

Nester 200244 Quasi-RCT |

Pharmacist medication reconciliation. Versus Nurse medication reconciliation. |

Consecutively admitted patients (n=100) to a tertiary care referral centre in the USA. Inclusion - over 18, responsive and able to speak English. Exclusion - intensive care, ambulatory surgical and labour-and-delivery units. | Medication discrepancies identified at admission. |

Nurses still performed medication history taking in the intervention group, but in all cases the intervention was conducted first. Unclear number of pharmacists involved. Allocation by alternation of consecutive admissions. |

|

Tong 201662 Australia RCT |

Early medication review and charting on admission involving a partnership between a pharmacist and a medical officer – pharmacist took medical history, VTE risk assessment and discussed medical and medication problems with admitting medical officer to agree a medication management plan. Versus Standard medication charting by medical officers of relevant teams, with subsequent medication reconciliation performed by pharmacist within 24 hours of admission. |

n=881 patients admitted to the general medical unit (GMU) and emergency short stay unit (ESSU) during pharmacist working hours (7am-9pm). Exclusion criteria: medication chart written by a doctor before pharmacist review; admitted to ESSU and not reviewed by a pharmacist. | Prescribing errors. ( | Pharmacist at admission strata. |

Table 4Summary of studies included in the review (pharmacist at discharge)

| Study | Intervention and comparison | Population | Outcomes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Al-Rashed 20023 RCT |

Pre-discharge counselling (24 hours before discharge) by the clinical pharmacist attached to that ward. Versus Normal hospital discharge policy – all patients, their GPs, district nurses and carers received a copy of the patient’s medication and information discharge summary sheet (MIDS) and patients received a medicine reminder card. Nurse went through (MIDS) with patients. |

n=83 patients admitted to 2 care of the elderly wards (UK). Inclusion criteria: >65 years, prescribed 4 or more regular items, were to be discharged to their own home and had an abbreviated mental score >7/10, English as a first language, and routine clinical pharmacist assessment that they could have problems with their medicines after discharge. | Readmission. | |

|

Bladh 20118 RCT |

Pharmacist discharge review Versus Usual care, which was received from the same group of physicians and nurses. No other details given. |

Patients (n=345) admitted on weekdays to the 2 internal medicine study wards at a university hospital in Sweden. Inclusion - capable of assessing their HRQL and giving written informed consent. Exclusion - poor Swedish language, planned discharge before intervention can be performed, transferred during their stay to other hospitals or wards not belonging to the Department of Medicine. | EQ-5D summarised index at 6 months follow-up. |

Pharmacist not ward based (no patient contact) until discussion at discharge however, pharmacist performed “continuous medication reviews” from medical records compared with usual care where there was no “continuous medication review”. Same physicians and nurses undertook care for the intervention and control. Intervention carried out by 1 of 3 pharmacists. |

|

Eggink 201015 RCT |

Pharmacist discharge review. Versus Nurse discharge review. |

Patients (n=89) to be discharged (no criteria given) in the Cardiology study ward within a teaching hospital in the Netherlands. Inclusion - patients have prescribed 5 or more medicines (from any class) at discharge. Exclusion - none stated. | Prescription errors identified during first outpatient follow-up. | Unclear number of pharmacists involved. |

|

Nickerson 200546 RCT |

Seamless care pharmacist at discharge including medication reconciliation, review of drug regime as part of comprehensive pharmaceutical care work-up, identification of problems and communication to community pharmacy, hospital staff and family physician, medication discharge counselling and a medication compliance chart Versus Standard care at discharge - discharge counselling and manual transcription of discharge notes from medical chart by nurse. |

n=253 patients admitted to 2 family practice units (Canada). Inclusion criteria: not discharged to another hospital, prescribed at least 1 medication at discharge, provided consent, agreement from community pharmacy, no previous study enrolment. Exclusion criteria: unable to answer study questions, unavailable for follow-up. | Prescriber errors-unresolved drug therapy inconsistencies and omissions. |

Table 5Clinical evidence summary: Regular in-hospital ward based pharmacy support compared to no ward-based pharmacist

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with no ward-based pharmacist | Risk difference with Regular in-hospital pharmacist support (95% CI) | ||||

| Mortality |

1060 (3 studies) 1 years |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 0.92 (0.72 to 1.16) | 198 per 1000 |

16 fewer per 1000 (from 55 fewer to 32 more) |

| Survival |

368 (1 study) 1 years |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | HR 0.94 (0.65 to 1.36) | Control group risk not provided | Absolute effect cannot be calculated |

| Future admissions to hospital (over 30 days) |

1892 (4 studies) 1 years |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa due to risk of bias | RR 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) | 384 per 1000 |

27 fewer per 1000 (from 65 fewer to 15 more) |

| Readmission |

592 (1 study) 30 days |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 0.92 (0.62 to 1.37) | 146 per 1000 |

12 fewer per 1000 (from 55 fewer to 54 more) |

| Prescribing errors medication appropriateness index |

811 (2 studies) at discharge |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ due to risk of bias, inconsistency | - | - |

The mean prescribing errors in the intervention groups was 0.02 lower (0.12 lower to 1.08 higher) |

| Prescribing errors medication appropriateness index |

613 (1 study) 30 days |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa due to risk of bias | - |

The mean prescribing errors in the control groups was 9.6 |

The mean prescribing errors in the intervention groups was 2.1 higher (0.45 to 3.75 higher) |

| Preventable adverse drug events |

790 (2 studies) until discharge |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision | RR 0.74 (0.06 to 8.57) | 54 per 1000 |

14 fewer per 1000 (from 51 fewer to 409 more) |

| Preventable adverse drug events |

588 (1 study) 90 days |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 0.77 (0.29 to 2.05) | 31 per 1000 |

7 fewer per 1000 (from 22 fewer to 33 more) |

| Adverse drug reactions |

85 (1 study) 6 months |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 1.47 (0.26 to 8.33) | 48 per 1000 |

23 more per 1000 (from 36 fewer to 352 more) |

| Length of stay (days) |

1116 (2 studies) in-hospital |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa due to risk of bias |

The mean length of stay in the control groups was 17.8 days |

The mean length of stay in the intervention groups was 1.74 lower (2.76 to 0.72 lower) | |

| Patient and/or carer satisfaction (1 month follow-up) |

172 (1 study) 1 months |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa due to risk of bias | RR 1.79 (1.38 to 2.32) | 446 per 1000 |

352 more per 1000 (from 169 more to 589 more) |

| Patient and/or carer satisfaction (at discharge) |

85 (1 study) at discharge |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 1.49 (1.09 to 2.03) | 548 per 1000 |

269 more per 1000 (from 49 more to 564 more) |

- (a)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- (b)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

- (c)

Downgraded by 1 because: The point estimate varies widely across studies, unexplained by subgroup analysis.

Table 6Clinical evidence summary: Pharmacist at admission compared to no ward-based pharmacist

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with no ward-based pharmacist | Risk difference with pharmacist at admission (95% CI) | ||||

| Medication errors identified at admission |

293 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision |

The mean medication errors identified in the control groups was 1.51 |

The mean medication reconciliation in the intervention groups was 0.36 higher (0.07 to 0.65 higher) | |

| Quality of life EQ-VAS index |

63 (1 study) 3 months |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision |

The mean quality of life in the control groups was 60.9 |

The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 6.2 higher (5.7 lower to 18.1 higher) | |

| Length of stay (hours) |

99 (1 study) in-hospital |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa due to risk of bias |

The mean length of stay in the control groups was 239.9 hours |

The mean length of stay in the intervention groups was 1.3 higher (108.96 lower to 111.56 higher) | |

| Admissions |

99 (1 study) 3 months |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision |

The mean admission in the control groups was 0.4 admissions per patient |

The mean admission in the intervention groups was 0.1 lower (0.38 lower to 0.18 higher) | |

| Mortality |

99 (1 study) 3 months |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision | RR 1.57 (0.55 to 4.46) | 102 per 1000 |

58 more per 1000 (from 46 fewer to 353 more) |

| Physician agreement |

457 (1 study) at admission |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision | RR 1.35 (1.13 to 1.63) | 437 per 1000 |

153 more per 1000 (from 57 more to 275 more) |

| Length of stay in acute admissions unit (AAU) (minutes) |

448 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 due to risk of bias | - | The mean length of stay in the control groups was 339 minutes. | The mean length of stay in intervention group was 3.2 min higher (26.49 lower to 32.89 higher) |

| Total medication errors within 24 hours of admission |

881 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 due to risk of bias | RR 0.05 (0.03 to 0.08) | 787 per 1000 | 748 fewer per 1000 (from 772 fewer to 763 fewer) |

- (a)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias.

- (b)

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

- (c)

The majority of the evidence had indirect outcomes.

Table 7Clinical evidence summary: Pharmacist at discharge compared to no ward-based pharmacist

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with no ward-pharmacist | Risk difference with pharmacist at discharge (95% CI) | ||||

|

Quality of life Global health index |

204 (1 study) 6 months |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ due to risk of bias, imprecision |

The mean quality of life in the control groups was 2.77 |

The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.23 higher (0.02 lower to 0.48 higher) | |

|